LIST PRICE $17.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

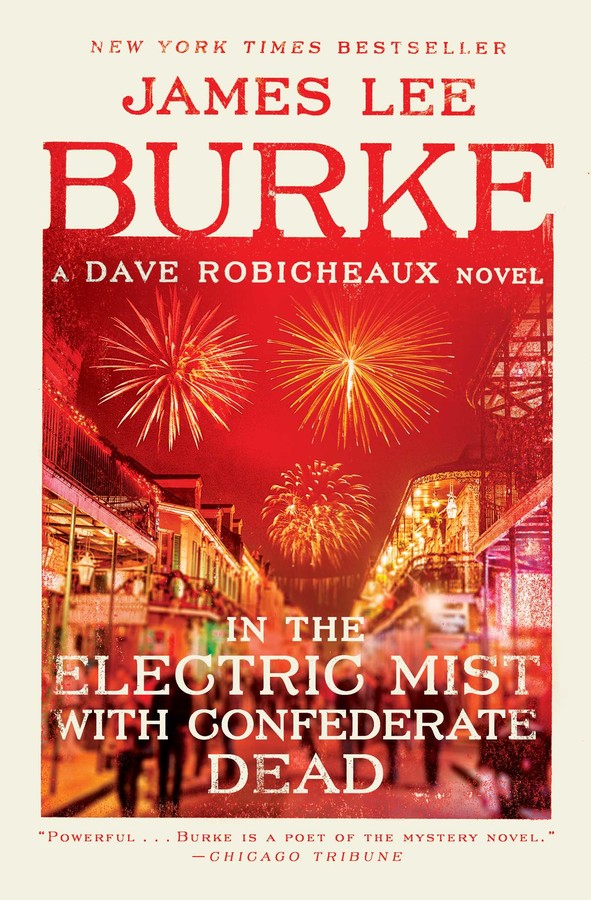

The sixth in the New York Times bestselling Dave Robicheaux series delivers a heart-pounding bayou manhunt—and features “one of the coolest, earthiest heroes in thrillerdom” (Entertainment Weekly).

When Hollywood invades New Iberia Parish to film a Civil War epic, restless specters waiting in the shadows for Louisiana detective Dave Robicheaux are reawakened—ghosts of a history best left undisturbed.

Hunting a serial killer preying on the lawless young, Robicheaux comes face-to-face with the elusive guardians of his darkest torments—who hold the key to his ultimate salvation or a final, fatal downfall.

When Hollywood invades New Iberia Parish to film a Civil War epic, restless specters waiting in the shadows for Louisiana detective Dave Robicheaux are reawakened—ghosts of a history best left undisturbed.

Hunting a serial killer preying on the lawless young, Robicheaux comes face-to-face with the elusive guardians of his darkest torments—who hold the key to his ultimate salvation or a final, fatal downfall.

Excerpt

In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead CHAPTER 1

THE SKY HAD gone black at sunset, and the storm had churned inland from the Gulf and drenched New Iberia and littered East Main with leaves and tree branches from the long canopy of oaks that covered the street from the old brick post office to the drawbridge over Bayou Teche at the edge of town. The air was cool now, laced with light rain, heavy with the fecund smell of wet humus, night-blooming jasmine, roses, and new bamboo. I was about to stop my truck at Del’s and pick up three crawfish dinners to go when a lavender Cadillac fishtailed out of a side street, caromed off a curb, bounced a hubcap up on a sidewalk, and left long serpentine lines of tire prints through the glazed pools of yellow light from the street lamps.

I was off duty, tired, used up after a day of searching for a nineteen-year-old girl in the woods, then finding her where she had been left in the bottom of a coulee, her mouth and wrists wrapped with electrician’s tape. Already I had tried to stop thinking about the rest of it. The medical examiner was a kind man. He bagged the body before any news people or family members got there.

I don’t like to bust drunk drivers. I don’t like to listen to their explanations, watch their pitiful attempts to affect sobriety, or see the sheen of fear break out in their eyes when they realize they’re headed for the drunk tank with little to look forward to in the morning except the appearance of their names in the newspaper. Or maybe in truth I just don’t like to see myself when I look into their faces.

But I didn’t believe this particular driver could make it another block without ripping the side off a parked car or plowing the Cadillac deep into someone’s shrubbery. I plugged my portable bubble into the cigarette lighter, clamped the magnets on the truck’s roof, and pulled him to the curb in front of the Shadows, a huge brick, white-columned antebellum home built on Bayou Teche in 1831.

I had my Iberia Parish Sheriff’s Department badge opened in my palm when I walked up to his window.

“Can I see your driver’s license, please?”

He had rugged good looks, a Roman profile, square shoulders, and broad hands. When he smiled I saw that his teeth were capped. The woman next to him wore her hair in blond ringlets and her body was as lithe, tanned, and supple-looking as an Olympic swimmer’s. Her mouth looked as red and vulnerable as a rose. She also looked like she was seasick.

“You want driver’s what?” he said, trying to focus evenly on my face. Inside the car I could smell a drowsy, warm odor, like the smell of smoke rising from a smoldering pile of wet leaves.

“Your driver’s license,” I repeated. “Please take it out of your billfold and hand it to me.”

“Oh, yeah, sure, wow,” he said. “I was really careless back there. I’m sorry about that. I really am.”

He got his license out of his wallet, dropped it in his lap, found it again, then handed it to me, trying to keep his eyes from drifting off my face. His breath smelled like fermented fruit that had been corked up for a long time in a stone jug.

I looked at the license under the street lamp.

“You’re Elrod T. Sykes?” I asked.

“Yes, sir, that’s who I am.”

“Would you step out of the car, Mr. Sykes?”

“Yes, sir, anything you say.”

He was perhaps forty, but in good shape. He wore a light-blue golf shirt, loafers, and gray slacks that hung loosely on his flat stomach and narrow hips. He swayed slightly and propped one hand on the door to steady himself.

“We have a problem here, Mr. Sykes. I think you’ve been smoking marijuana in your automobile.”

“Marijuana . . . Boy, that’d be bad, wouldn’t it?”

“I think your lady friend just ate the roach, too.”

“That wouldn’t be good, no, sir, not at all.” He shook his head profoundly.

“Well, we’re going to let the reefer business slide for now. But I’m afraid you’re under arrest for driving while intoxicated.”

“That’s very bad news. This definitely was not on my agenda this evening.” He widened his eyes and opened and closed his mouth as though he were trying to clear an obstruction in his ear canals. “Say, do you recognize me? What I mean is, there’re news people who’d really like to put my ham hocks in the frying pan. Believe me, sir, I don’t need this. I cain’t say that enough.”

“I’m going to drive you just down the street to the city jail, Mr. Sykes. Then I’ll send a car to take Ms. Drummond to wherever she’s staying. But your Cadillac will be towed to the pound.”

He let out his breath in a long sigh. I turned my face away.

“You go to the movies, huh?” he said.

“Yeah, I always enjoyed your films. Ms. Drummond’s, too. Take your car keys out of the ignition, please.”

“Yeah, sure,” he said, despondently.

He leaned into the window and pulled the keys out of the ignition.

“El, do something,” the woman said.

He straightened his back and looked at me.

“I feel real bad about this,” he said. “Can I make a contribution to Mothers Against Drunk Driving, or something like that?”

In the lights from the city park, I could see the rain denting the surface of Bayou Teche.

“Mr. Sykes, you’re under arrest. You can remain silent if you wish, or if you wish to speak, anything you say can be used against you,” I said. “As a long-time fan of your work, I recommend that you not say anything else. Particularly about contributions.”

“It doesn’t look like you mess around. Were you ever a Texas ranger? They don’t mess around, either. You talk back to those boys and they’ll hit you upside the head.”

“Well, we don’t do that here,” I said. I put my hand under his arm and led him to my truck. I opened the door for him and helped him inside. “You’re not going to get sick in my truck, are you?”

“No, sir, I’m just fine.”

“That’s good. I’ll be right with you.”

I walked back to the Cadillac and tapped on the glass of the passenger’s door. The woman, whose name was Kelly Drummond, rolled down the window. Her face was turned up into mine. Her eyes were an intense, deep green. She wet her lips, and I saw a smear of lipstick on her teeth.

“You’ll have to wait here about ten minutes, then someone will drive you home,” I said.

“Officer, I’m responsible for this,” she said. “We were having an argument. Elrod’s a good driver. I don’t think he should be punished because I got him upset. Can I get out of the car? My neck hurts.”

“I suggest you lock your automobile and stay where you are, Ms. Drummond. I also suggest you do some research into the laws governing the possession of narcotics in the state of Louisiana.”

“Wow, I mean, it’s not like we hurt anybody. This is going to get Elrod in a lot of trouble with Mikey. Why don’t you show a little compassion?”

“Mikey?”

“Our director, the guy who’s bringing about ten million dollars into your little town. Can I get out of the car now? I really don’t want a neck like Quasimodo.”

“You can go anywhere you want. There’s a pay phone in the poolroom you can use to call a bondsman. If I were you, I wouldn’t go down to the station to help Mr. Sykes, not until you shampoo the Mexican laughing grass out of your hair.”

“Boy, talk about wearing your genitalia outside your pants. Where’d they come up with you?”

I walked back to my truck and got in.

“Look, maybe I can be a friend of the court,” Elrod Sykes said.

“What?”

“Isn’t that what they call it? There’s nothing wrong with that, is there? Man, I can really do without this bust.”

“Few people standing before a judge ever expected to be there,” I said, and started the engine.

He was quiet while I made a U-turn and headed for the city police station. He seemed to be thinking hard about something. Then he said: “Listen, I know where there’s a body. I saw it. Nobody’d pay me any mind, but I saw the dadburn thing. That’s a fact.”

“You saw what?”

“A colored, I mean a black person, it looked like. Just a big dry web of skin, with bones inside it. Like a big rat’s nest.”

“Where was this?”

“Out in the Atchafalaya swamp, about four days ago. We were shooting some scenes by an Indian reservation or something. I wandered back in these willows to take a leak and saw it sticking out of a sandbar.”

“And you didn’t bother to report it until now?”

“I told Mikey. He said it was probably bones that had washed out of an Indian burial mound or something. Mikey’s kind of hard-nosed. He said the last thing we needed was trouble with either cops or university archaeologists.”

“We’ll talk about it tomorrow, Mr. Sykes.”

“You don’t pay me much mind, either. But that’s all right. I told you what I saw. Y’all can do what you want to with it.”

He looked straight ahead through the beads of water on the window. His handsome face was wan, tired, more sober now, resigned perhaps to a booking room, drunk-tank scenario he knew all too well. I remembered two or three wire-service stories about him over the last few years—a brawl with a couple of cops in Dallas or Fort Worth, a violent ejection from a yacht club in Los Angeles, and a plea on a cocaine-possession bust. I had heard that bean sprouts, mineral water, and the sober life had become fashionable in Hollywood. It looked like Elrod Sykes had arrived late at the depot.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t get your name,” he said.

“Dave Robicheaux.”

“Well, you see, Mr. Robicheaux, a lot of people don’t believe me when I tell them I see things. But the truth is, I see things all the time, like shadows moving around behind a veil. In my family we call it ‘touched.’ When I was a little boy, my grandpa told me, ‘Son, the Lord done touched you. He give you a third eye to see things that other people cain’t. But it’s a gift from the Lord, and you mustn’t never use it otherwise.’ I haven’t ever misused the gift, either, Mr. Robicheaux, even though I’ve done a lot of other things I’m not proud of. So I don’t care if people think I lasered my head with too many recreational chemicals or not.”

“I see.”

He was quiet again. We were almost to the jail now. The wind blew raindrops out of the oak trees, and the moon edged the storm clouds with a metallic silver light. He rolled down his window halfway and breathed in the cool smell of the night.

“But if that was an Indian washed out of a burial mound instead of a colored man, I wonder what he was doing with a chain wrapped around him,” he said.

I slowed the truck and pulled it to the curb.

“Say that again,” I said.

“There was a rusted chain, I mean with links as big as my fist, crisscrossed around his rib cage.”

I studied his face. It was innocuous, devoid of intention, pale in the moonlight, already growing puffy with hangover.

“You want some slack on the DWI for your knowledge about this body, Mr. Sykes?”

“No, sir, I just wanted to tell you what I saw. I shouldn’t have been driving. Maybe you kept me from having an accident.”

“Some people might call that jailhouse humility. What do you think?”

“I think you might make a tough film director.”

“Can you find that sandbar again?”

“Yes, sir, I believe I can.”

“Where are you and Ms. Drummond staying?”

“The studio rented us a house out on Spanish Lake.”

“I’m going to make a confession to you, Mr. Sykes. DWIs are a pain in the butt. Also I’m on city turf and doing their work. If I take y’all home, can I have your word you’ll remain there until tomorrow morning?”

“Yes, sir, you sure can.”

“But I want you in my office by nine A.M.”

“Nine A.M. You got it. Absolutely. I really appreciate this.”

The transformation in his face was immediate, as though liquified ambrosia had been infused in the veins of a starving man. Then as I turned the truck around in the middle of the street to pick up the actress whose name was Kelly Drummond, he said something that gave me pause about his level of sanity.

“Does anybody around here ever talk about Confederate soldiers out on that lake?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Just what I said. Does anybody ever talk about guys in gray or butternut-brown uniforms out there? A bunch of them, at night, out there in the mist.”

“Aren’t y’all making a film about the War Between the States? Are you talking about actors?” I looked sideways at him. His eyes were straight forward, focused on some private thought right outside the windshield.

“No, these guys weren’t actors,” he said. “They’d been shot up real bad. They looked hungry, too. It happened right around here, didn’t it?”

“What?”

“The battle.”

“I’m afraid I’m not following you, Mr. Sykes.”

Up ahead I saw Kelly Drummond walking in her spiked heels and Levi’s toward Tee Neg’s poolroom.

“Yeah, you do,” he said. “You believe when most people don’t, Mr. Robicheaux. You surely do. And when I say you believe, you know exactly what I’m talking about.”

He looked confidently, serenely, into my face and winked with one blood-flecked eye.

THE SKY HAD gone black at sunset, and the storm had churned inland from the Gulf and drenched New Iberia and littered East Main with leaves and tree branches from the long canopy of oaks that covered the street from the old brick post office to the drawbridge over Bayou Teche at the edge of town. The air was cool now, laced with light rain, heavy with the fecund smell of wet humus, night-blooming jasmine, roses, and new bamboo. I was about to stop my truck at Del’s and pick up three crawfish dinners to go when a lavender Cadillac fishtailed out of a side street, caromed off a curb, bounced a hubcap up on a sidewalk, and left long serpentine lines of tire prints through the glazed pools of yellow light from the street lamps.

I was off duty, tired, used up after a day of searching for a nineteen-year-old girl in the woods, then finding her where she had been left in the bottom of a coulee, her mouth and wrists wrapped with electrician’s tape. Already I had tried to stop thinking about the rest of it. The medical examiner was a kind man. He bagged the body before any news people or family members got there.

I don’t like to bust drunk drivers. I don’t like to listen to their explanations, watch their pitiful attempts to affect sobriety, or see the sheen of fear break out in their eyes when they realize they’re headed for the drunk tank with little to look forward to in the morning except the appearance of their names in the newspaper. Or maybe in truth I just don’t like to see myself when I look into their faces.

But I didn’t believe this particular driver could make it another block without ripping the side off a parked car or plowing the Cadillac deep into someone’s shrubbery. I plugged my portable bubble into the cigarette lighter, clamped the magnets on the truck’s roof, and pulled him to the curb in front of the Shadows, a huge brick, white-columned antebellum home built on Bayou Teche in 1831.

I had my Iberia Parish Sheriff’s Department badge opened in my palm when I walked up to his window.

“Can I see your driver’s license, please?”

He had rugged good looks, a Roman profile, square shoulders, and broad hands. When he smiled I saw that his teeth were capped. The woman next to him wore her hair in blond ringlets and her body was as lithe, tanned, and supple-looking as an Olympic swimmer’s. Her mouth looked as red and vulnerable as a rose. She also looked like she was seasick.

“You want driver’s what?” he said, trying to focus evenly on my face. Inside the car I could smell a drowsy, warm odor, like the smell of smoke rising from a smoldering pile of wet leaves.

“Your driver’s license,” I repeated. “Please take it out of your billfold and hand it to me.”

“Oh, yeah, sure, wow,” he said. “I was really careless back there. I’m sorry about that. I really am.”

He got his license out of his wallet, dropped it in his lap, found it again, then handed it to me, trying to keep his eyes from drifting off my face. His breath smelled like fermented fruit that had been corked up for a long time in a stone jug.

I looked at the license under the street lamp.

“You’re Elrod T. Sykes?” I asked.

“Yes, sir, that’s who I am.”

“Would you step out of the car, Mr. Sykes?”

“Yes, sir, anything you say.”

He was perhaps forty, but in good shape. He wore a light-blue golf shirt, loafers, and gray slacks that hung loosely on his flat stomach and narrow hips. He swayed slightly and propped one hand on the door to steady himself.

“We have a problem here, Mr. Sykes. I think you’ve been smoking marijuana in your automobile.”

“Marijuana . . . Boy, that’d be bad, wouldn’t it?”

“I think your lady friend just ate the roach, too.”

“That wouldn’t be good, no, sir, not at all.” He shook his head profoundly.

“Well, we’re going to let the reefer business slide for now. But I’m afraid you’re under arrest for driving while intoxicated.”

“That’s very bad news. This definitely was not on my agenda this evening.” He widened his eyes and opened and closed his mouth as though he were trying to clear an obstruction in his ear canals. “Say, do you recognize me? What I mean is, there’re news people who’d really like to put my ham hocks in the frying pan. Believe me, sir, I don’t need this. I cain’t say that enough.”

“I’m going to drive you just down the street to the city jail, Mr. Sykes. Then I’ll send a car to take Ms. Drummond to wherever she’s staying. But your Cadillac will be towed to the pound.”

He let out his breath in a long sigh. I turned my face away.

“You go to the movies, huh?” he said.

“Yeah, I always enjoyed your films. Ms. Drummond’s, too. Take your car keys out of the ignition, please.”

“Yeah, sure,” he said, despondently.

He leaned into the window and pulled the keys out of the ignition.

“El, do something,” the woman said.

He straightened his back and looked at me.

“I feel real bad about this,” he said. “Can I make a contribution to Mothers Against Drunk Driving, or something like that?”

In the lights from the city park, I could see the rain denting the surface of Bayou Teche.

“Mr. Sykes, you’re under arrest. You can remain silent if you wish, or if you wish to speak, anything you say can be used against you,” I said. “As a long-time fan of your work, I recommend that you not say anything else. Particularly about contributions.”

“It doesn’t look like you mess around. Were you ever a Texas ranger? They don’t mess around, either. You talk back to those boys and they’ll hit you upside the head.”

“Well, we don’t do that here,” I said. I put my hand under his arm and led him to my truck. I opened the door for him and helped him inside. “You’re not going to get sick in my truck, are you?”

“No, sir, I’m just fine.”

“That’s good. I’ll be right with you.”

I walked back to the Cadillac and tapped on the glass of the passenger’s door. The woman, whose name was Kelly Drummond, rolled down the window. Her face was turned up into mine. Her eyes were an intense, deep green. She wet her lips, and I saw a smear of lipstick on her teeth.

“You’ll have to wait here about ten minutes, then someone will drive you home,” I said.

“Officer, I’m responsible for this,” she said. “We were having an argument. Elrod’s a good driver. I don’t think he should be punished because I got him upset. Can I get out of the car? My neck hurts.”

“I suggest you lock your automobile and stay where you are, Ms. Drummond. I also suggest you do some research into the laws governing the possession of narcotics in the state of Louisiana.”

“Wow, I mean, it’s not like we hurt anybody. This is going to get Elrod in a lot of trouble with Mikey. Why don’t you show a little compassion?”

“Mikey?”

“Our director, the guy who’s bringing about ten million dollars into your little town. Can I get out of the car now? I really don’t want a neck like Quasimodo.”

“You can go anywhere you want. There’s a pay phone in the poolroom you can use to call a bondsman. If I were you, I wouldn’t go down to the station to help Mr. Sykes, not until you shampoo the Mexican laughing grass out of your hair.”

“Boy, talk about wearing your genitalia outside your pants. Where’d they come up with you?”

I walked back to my truck and got in.

“Look, maybe I can be a friend of the court,” Elrod Sykes said.

“What?”

“Isn’t that what they call it? There’s nothing wrong with that, is there? Man, I can really do without this bust.”

“Few people standing before a judge ever expected to be there,” I said, and started the engine.

He was quiet while I made a U-turn and headed for the city police station. He seemed to be thinking hard about something. Then he said: “Listen, I know where there’s a body. I saw it. Nobody’d pay me any mind, but I saw the dadburn thing. That’s a fact.”

“You saw what?”

“A colored, I mean a black person, it looked like. Just a big dry web of skin, with bones inside it. Like a big rat’s nest.”

“Where was this?”

“Out in the Atchafalaya swamp, about four days ago. We were shooting some scenes by an Indian reservation or something. I wandered back in these willows to take a leak and saw it sticking out of a sandbar.”

“And you didn’t bother to report it until now?”

“I told Mikey. He said it was probably bones that had washed out of an Indian burial mound or something. Mikey’s kind of hard-nosed. He said the last thing we needed was trouble with either cops or university archaeologists.”

“We’ll talk about it tomorrow, Mr. Sykes.”

“You don’t pay me much mind, either. But that’s all right. I told you what I saw. Y’all can do what you want to with it.”

He looked straight ahead through the beads of water on the window. His handsome face was wan, tired, more sober now, resigned perhaps to a booking room, drunk-tank scenario he knew all too well. I remembered two or three wire-service stories about him over the last few years—a brawl with a couple of cops in Dallas or Fort Worth, a violent ejection from a yacht club in Los Angeles, and a plea on a cocaine-possession bust. I had heard that bean sprouts, mineral water, and the sober life had become fashionable in Hollywood. It looked like Elrod Sykes had arrived late at the depot.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t get your name,” he said.

“Dave Robicheaux.”

“Well, you see, Mr. Robicheaux, a lot of people don’t believe me when I tell them I see things. But the truth is, I see things all the time, like shadows moving around behind a veil. In my family we call it ‘touched.’ When I was a little boy, my grandpa told me, ‘Son, the Lord done touched you. He give you a third eye to see things that other people cain’t. But it’s a gift from the Lord, and you mustn’t never use it otherwise.’ I haven’t ever misused the gift, either, Mr. Robicheaux, even though I’ve done a lot of other things I’m not proud of. So I don’t care if people think I lasered my head with too many recreational chemicals or not.”

“I see.”

He was quiet again. We were almost to the jail now. The wind blew raindrops out of the oak trees, and the moon edged the storm clouds with a metallic silver light. He rolled down his window halfway and breathed in the cool smell of the night.

“But if that was an Indian washed out of a burial mound instead of a colored man, I wonder what he was doing with a chain wrapped around him,” he said.

I slowed the truck and pulled it to the curb.

“Say that again,” I said.

“There was a rusted chain, I mean with links as big as my fist, crisscrossed around his rib cage.”

I studied his face. It was innocuous, devoid of intention, pale in the moonlight, already growing puffy with hangover.

“You want some slack on the DWI for your knowledge about this body, Mr. Sykes?”

“No, sir, I just wanted to tell you what I saw. I shouldn’t have been driving. Maybe you kept me from having an accident.”

“Some people might call that jailhouse humility. What do you think?”

“I think you might make a tough film director.”

“Can you find that sandbar again?”

“Yes, sir, I believe I can.”

“Where are you and Ms. Drummond staying?”

“The studio rented us a house out on Spanish Lake.”

“I’m going to make a confession to you, Mr. Sykes. DWIs are a pain in the butt. Also I’m on city turf and doing their work. If I take y’all home, can I have your word you’ll remain there until tomorrow morning?”

“Yes, sir, you sure can.”

“But I want you in my office by nine A.M.”

“Nine A.M. You got it. Absolutely. I really appreciate this.”

The transformation in his face was immediate, as though liquified ambrosia had been infused in the veins of a starving man. Then as I turned the truck around in the middle of the street to pick up the actress whose name was Kelly Drummond, he said something that gave me pause about his level of sanity.

“Does anybody around here ever talk about Confederate soldiers out on that lake?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Just what I said. Does anybody ever talk about guys in gray or butternut-brown uniforms out there? A bunch of them, at night, out there in the mist.”

“Aren’t y’all making a film about the War Between the States? Are you talking about actors?” I looked sideways at him. His eyes were straight forward, focused on some private thought right outside the windshield.

“No, these guys weren’t actors,” he said. “They’d been shot up real bad. They looked hungry, too. It happened right around here, didn’t it?”

“What?”

“The battle.”

“I’m afraid I’m not following you, Mr. Sykes.”

Up ahead I saw Kelly Drummond walking in her spiked heels and Levi’s toward Tee Neg’s poolroom.

“Yeah, you do,” he said. “You believe when most people don’t, Mr. Robicheaux. You surely do. And when I say you believe, you know exactly what I’m talking about.”

He looked confidently, serenely, into my face and winked with one blood-flecked eye.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (November 27, 2018)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982100315

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead Trade Paperback 9781982100315

- Author Photo (jpg): James Lee Burke Photograph by James McDavid(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit