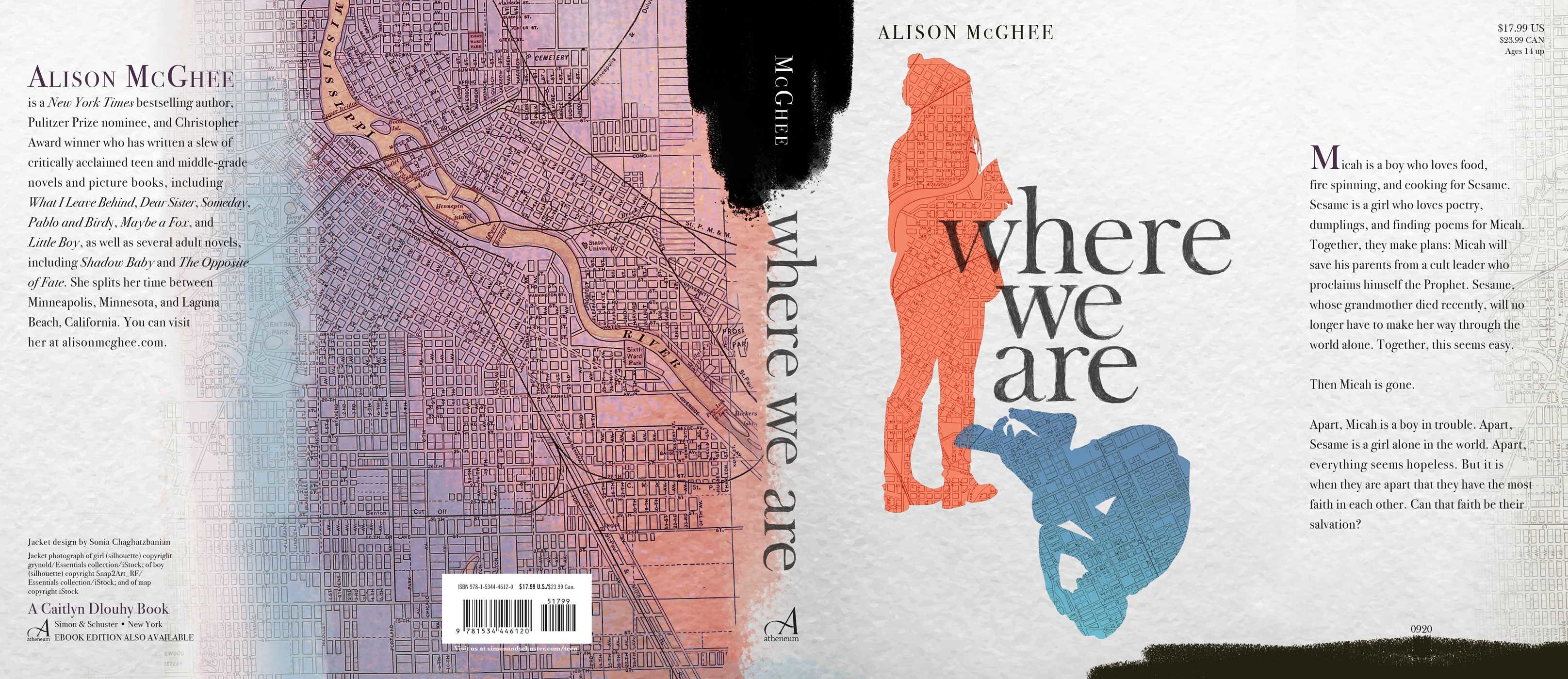

Where We Are

By Alison McGhee

LIST PRICE $18.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

From New York Times bestselling author Alison McGhee comes a stunning and heartbreaking story of two teens who fight to reunite when one of them is caught in the web of a sinister cult.

Micah and Sesame are true best friends. They safeguard each other’s secrets and share their dreams. Micah wants to save his parents from the cult leader who calls himself “the Prophet.” Sesame recently lost the last of her own family—her grandmother—and plans to keep a low profile until she turns eighteen to avoid foster care. Together, they never doubt they can build the futures they want.

Until Micah disappears. The Prophet has taken Micah, his parents, and the rest of his followers underground. And trying to take on the Prophet in isolation, surrounded by his followers, proves to be a dangerous mistake that leaves Micah hopeless and at the Prophet’s mercy.

Sesame, left alone, is wracked with fear over what could be happening to Micah. Never before have the two of them been so far apart—or needed each other more. But their faith in each other never wavers, and that may just be enough to save them both.

Micah and Sesame are true best friends. They safeguard each other’s secrets and share their dreams. Micah wants to save his parents from the cult leader who calls himself “the Prophet.” Sesame recently lost the last of her own family—her grandmother—and plans to keep a low profile until she turns eighteen to avoid foster care. Together, they never doubt they can build the futures they want.

Until Micah disappears. The Prophet has taken Micah, his parents, and the rest of his followers underground. And trying to take on the Prophet in isolation, surrounded by his followers, proves to be a dangerous mistake that leaves Micah hopeless and at the Prophet’s mercy.

Sesame, left alone, is wracked with fear over what could be happening to Micah. Never before have the two of them been so far apart—or needed each other more. But their faith in each other never wavers, and that may just be enough to save them both.

Excerpt

Chapter 1: Micah 1 Micah

WHEN THE KNOCK came, my parents were upstairs getting ready for bed, so I answered the door. It was weird to see Deeson, the head acolyte, outside of Reflection. Weirder yet to see him in a black hoodie. Not the type, Deeson. In fact, the complete opposite of a black hoodie type is Deeson. I mean, he’d tied the hoodie strings underneath his chin. But still, there he was, white face tilted up beneath the hood, appraising me.

“Bless the child, Acolyte Deeson,” I said. That was—is—how members of the Living Lights greet each other.

“Gather your parents and your duffels and follow me,” he said. “We are called to the South Compound.”

See how he didn’t address me as Acolyte Stone? That’s Deeson. He has dead eyes. The Prophet once praised Deeson’s eyes in Reflection, saying that they revealed purity of purpose. What purpose, though? That’s what I wanted to ask but didn’t. Like everyone else, I didn’t ask questions during Reflection. One day into our underground life, I think about that. How none of us questioned the Prophet or anything he said.

Our duffels were prepacked and waiting at the top of the stairs: the white robes and white underwear we had all been issued months before, a gallon jug of water each, the Reflections book that the Prophet had written and self-published and that the Living Lights used instead of a Bible, and a brush or comb.

My parents looked up at me from the bathroom sink, where they were brushing their teeth—they always brushed their teeth at the same time—when I told them that Deeson was there, it was time to go to the South Compound, get the duffels and follow him. They didn’t ask any questions. They just nodded. That’s something else I think about now. They rinsed and spat and then the three of us packed our toothbrushes into our duffels and went downstairs where Deeson was waiting by the door.

“Bless the child, Acolytes Stone,” he said to my parents—see, he called them acolytes—and then, “Did you send in the school excuse note last week, as instructed?”

My father nodded.

“Um, what excuse note?” I said.

“You are hereby excused from high school beginning tomorrow through the end of winter break for a family activity,” Deeson said. “Fully in compliance with Minneapolis Public Schools attendance policy.”

I stared at my parents, but they didn’t meet my eyes. What the hell? No one had told me about this. This was a Wednesday night and there was still a week of school left before winter break began. In compliance or not, no way could I miss that much school, not junior year. And “family activity”? Deep inside me an alarm went off, an invisible, insistent alarm. Which got louder when Deeson spoke again.

“Phones,” he said, and pointed at the kitchen counter.

Wait, what? Phones?

That wasn’t part of Sesame’s and my plan. The Prophet had been hinting that the time was nigh for the Living Lights to begin Phase Two of the project. He had bought an abandoned building somewhere in South Minneapolis—no one knew where, exactly—with the money he’d collected from the congregation, and the plan was to turn it into some kind of Living Lights Retreat Center.

Phase One: buying the building, which he named the South Compound.

Phase Two: everyone training together for retreat center life.

Phase Three: opening the retreat center.

Phase Four: Taking over the world? Making the Prophet the divine ruler of all? Shit, I don’t know. I quit listening about five minutes into every one of his lectures.

Anyway.

Sesame’s and my plan if they actually came for us: I would bring my phone and text her once we got to the South Compound and I knew for sure where we were.

So the phones moment was the first moment that I felt uneasy. Truly uneasy, I mean, not laugh-about-the-doings-of-the-Living-Lights-with-Sesame uneasy, not this’ll-be-a-great-story-someday uneasy. Without my phone, a way to keep it charged, and enough of a signal, I would be alone, no way to contact Ses or anyone. Why hadn’t we thought of that? Why hadn’t we thought things through? Why hadn’t we taken things seriously?

Correction: Why hadn’t I taken things seriously?

Sesame had, from the start.

The Hello Kitty notebook that Vong, the second grader she tutors at Greenway Elementary, gave me was in my duffel. So was the matching Hello Kitty pencil, which Vong also gave me. Those things I had hidden at the bottom, wrapped inside one of the white robes. Call me prescient or call me dumb lucky, but the notebook was there. Maybe I could write to Ses, a note on notebook paper, from wherever we were going. But how would she get it? I don’t have a stamp and she doesn’t have a mailing address, and even though the Jameses would give it to her if I sent it to them, I don’t know their address.

Hey, Ses. Can you hear me? Can you read me, coming at you from here in the laundry room of the South Compound, where I have been placed in detention? Yeah, that’s right. Day one and I’m already in detention. I’m sitting in the corner, avoiding dripping white robes and writing in Hello Kitty.

Last night Deeson opened the door of our house, looked both ways, and motioned us out. My dad turned down the thermostat before leaving, which made the silent alarm inside me go off yet again. Deeson took the key from my mother’s hand and locked the front door. I thought fast. Fast born of fear. Or dread, is a more accurate word. The sight of our three phones lying together on the counter next to the toaster, little rectangular corpses, panicked me. Out into the frigid December night we went. The Prophet’s white passenger van was pulled up to the curb. No one was out. Why would they be? Even dogs don’t want to be outside on a night like that.

“Acolyte Deeson, hold up,” I said. “I have to go to the bathroom.”

My parents were getting into the van, duffels over their shoulders. A hand came forward and took my mom’s duffel from her. It was impossible to see more than shadows in the dark interior, but it was clear that other members of the Living Lights were already in there.

“The South Compound is nearby,” he said. “You can hold it.”

“I don’t think I can, though,” I said, and I shifted my weight from one leg to the other the way little kids do. “It’s bad.”

He frowned but gave me the key and jerked his thumb toward our front door, and I ran back in. Grabbed my phone and shoved it down my underwear and then, just in case, wrote a note in dry-erase on the whiteboard for Sesame, because being Ses, she would come by as soon as she figured out I was gone.

Hello Kitty,

Please be on the lookout for my GPS. I think it’s somewhere in the neighborhood.

xo

Then I ran back out without peeing. Which actually I did have to, but too late now. Deeson was waiting for me outside the door, that Deeson look in his eyes. He held up his hands like he was surrendering, which was weird, but then he started patting me up and down like I’d set off an alarm at airport security. Shit. He didn’t even hesitate when he got to my crotch. Fuck you, Deeson.

“Remove the phone,” he said, a triumphant sound in his voice.

“I need it, though,” I said, “for… homework. Writing papers. I can’t get behind, it’s my junior year.”

Like somehow “junior year,” that important pre-college-application year, would mean anything to him.

“Remove the phone or I will remove it for you,” Deeson said.

He made me bring it back into the house, watched as I put it back on the counter next to my parents’ phones, then took the key after I locked up again. My parents were sitting on a bench in the van—it had bench seats, like pews in a church, homemade—and I squeezed in next to them, against the side. They gave me a silent, disapproving look. There were others all around us, but no one in the van said a word. Deeson was up front, driving, and as he pulled away from the curb, a panel slid down from the ceiling and closed us all in. It was dark, Ses, darker than the darkest of dark winter nights in your house.

We drove.

We drove, and drove, and drove, and it must have been hours, because I fell asleep against the cold steel wall of the van. I fell asleep and then jerked awake, fell asleep and jerked awake. I had to pee so bad. Deeson was lying when he said the South Compound was close by. The Prophet was lying when he said he’d bought an abandoned building in South Minneapolis. We are nowhere near South Minneapolis. My message on the whiteboard doesn’t make any sense now.

I don’t know where we are.

I don’t know where we are, Sesame.

Have you been to the house yet? Did you figure out right away that the time had come and that I was gone? Did you remember where the fake rock is hidden? Was it covered with snow?

I can’t send you my coordinates, Sesame, because I don’t know where I am.

I screwed up, Ses. Big-time.

I got sucked into something bigger than I ever thought it could be and now I’m stuck. Here in the laundry room. Where I am temporarily “detained.” My attempt to bring the phone was an infraction, which is a thing here, and the laundry room is the punishment. There’s a wire screen near the ceiling, which is low, and it leads into a dark space. Maybe it’s a crawl space. I can’t tell. But it must be close to the outside, because last night when I couldn’t sleep I heard faint sounds from the outside world. Sirens once in a while, police or ambulance, I can’t tell. Every once in a while, the bark of a dog. So I know that the outside world is still there.

WHEN THE KNOCK came, my parents were upstairs getting ready for bed, so I answered the door. It was weird to see Deeson, the head acolyte, outside of Reflection. Weirder yet to see him in a black hoodie. Not the type, Deeson. In fact, the complete opposite of a black hoodie type is Deeson. I mean, he’d tied the hoodie strings underneath his chin. But still, there he was, white face tilted up beneath the hood, appraising me.

“Bless the child, Acolyte Deeson,” I said. That was—is—how members of the Living Lights greet each other.

“Gather your parents and your duffels and follow me,” he said. “We are called to the South Compound.”

See how he didn’t address me as Acolyte Stone? That’s Deeson. He has dead eyes. The Prophet once praised Deeson’s eyes in Reflection, saying that they revealed purity of purpose. What purpose, though? That’s what I wanted to ask but didn’t. Like everyone else, I didn’t ask questions during Reflection. One day into our underground life, I think about that. How none of us questioned the Prophet or anything he said.

Our duffels were prepacked and waiting at the top of the stairs: the white robes and white underwear we had all been issued months before, a gallon jug of water each, the Reflections book that the Prophet had written and self-published and that the Living Lights used instead of a Bible, and a brush or comb.

My parents looked up at me from the bathroom sink, where they were brushing their teeth—they always brushed their teeth at the same time—when I told them that Deeson was there, it was time to go to the South Compound, get the duffels and follow him. They didn’t ask any questions. They just nodded. That’s something else I think about now. They rinsed and spat and then the three of us packed our toothbrushes into our duffels and went downstairs where Deeson was waiting by the door.

“Bless the child, Acolytes Stone,” he said to my parents—see, he called them acolytes—and then, “Did you send in the school excuse note last week, as instructed?”

My father nodded.

“Um, what excuse note?” I said.

“You are hereby excused from high school beginning tomorrow through the end of winter break for a family activity,” Deeson said. “Fully in compliance with Minneapolis Public Schools attendance policy.”

I stared at my parents, but they didn’t meet my eyes. What the hell? No one had told me about this. This was a Wednesday night and there was still a week of school left before winter break began. In compliance or not, no way could I miss that much school, not junior year. And “family activity”? Deep inside me an alarm went off, an invisible, insistent alarm. Which got louder when Deeson spoke again.

“Phones,” he said, and pointed at the kitchen counter.

Wait, what? Phones?

That wasn’t part of Sesame’s and my plan. The Prophet had been hinting that the time was nigh for the Living Lights to begin Phase Two of the project. He had bought an abandoned building somewhere in South Minneapolis—no one knew where, exactly—with the money he’d collected from the congregation, and the plan was to turn it into some kind of Living Lights Retreat Center.

Phase One: buying the building, which he named the South Compound.

Phase Two: everyone training together for retreat center life.

Phase Three: opening the retreat center.

Phase Four: Taking over the world? Making the Prophet the divine ruler of all? Shit, I don’t know. I quit listening about five minutes into every one of his lectures.

Anyway.

Sesame’s and my plan if they actually came for us: I would bring my phone and text her once we got to the South Compound and I knew for sure where we were.

So the phones moment was the first moment that I felt uneasy. Truly uneasy, I mean, not laugh-about-the-doings-of-the-Living-Lights-with-Sesame uneasy, not this’ll-be-a-great-story-someday uneasy. Without my phone, a way to keep it charged, and enough of a signal, I would be alone, no way to contact Ses or anyone. Why hadn’t we thought of that? Why hadn’t we thought things through? Why hadn’t we taken things seriously?

Correction: Why hadn’t I taken things seriously?

Sesame had, from the start.

The Hello Kitty notebook that Vong, the second grader she tutors at Greenway Elementary, gave me was in my duffel. So was the matching Hello Kitty pencil, which Vong also gave me. Those things I had hidden at the bottom, wrapped inside one of the white robes. Call me prescient or call me dumb lucky, but the notebook was there. Maybe I could write to Ses, a note on notebook paper, from wherever we were going. But how would she get it? I don’t have a stamp and she doesn’t have a mailing address, and even though the Jameses would give it to her if I sent it to them, I don’t know their address.

Hey, Ses. Can you hear me? Can you read me, coming at you from here in the laundry room of the South Compound, where I have been placed in detention? Yeah, that’s right. Day one and I’m already in detention. I’m sitting in the corner, avoiding dripping white robes and writing in Hello Kitty.

Last night Deeson opened the door of our house, looked both ways, and motioned us out. My dad turned down the thermostat before leaving, which made the silent alarm inside me go off yet again. Deeson took the key from my mother’s hand and locked the front door. I thought fast. Fast born of fear. Or dread, is a more accurate word. The sight of our three phones lying together on the counter next to the toaster, little rectangular corpses, panicked me. Out into the frigid December night we went. The Prophet’s white passenger van was pulled up to the curb. No one was out. Why would they be? Even dogs don’t want to be outside on a night like that.

“Acolyte Deeson, hold up,” I said. “I have to go to the bathroom.”

My parents were getting into the van, duffels over their shoulders. A hand came forward and took my mom’s duffel from her. It was impossible to see more than shadows in the dark interior, but it was clear that other members of the Living Lights were already in there.

“The South Compound is nearby,” he said. “You can hold it.”

“I don’t think I can, though,” I said, and I shifted my weight from one leg to the other the way little kids do. “It’s bad.”

He frowned but gave me the key and jerked his thumb toward our front door, and I ran back in. Grabbed my phone and shoved it down my underwear and then, just in case, wrote a note in dry-erase on the whiteboard for Sesame, because being Ses, she would come by as soon as she figured out I was gone.

Hello Kitty,

Please be on the lookout for my GPS. I think it’s somewhere in the neighborhood.

xo

Then I ran back out without peeing. Which actually I did have to, but too late now. Deeson was waiting for me outside the door, that Deeson look in his eyes. He held up his hands like he was surrendering, which was weird, but then he started patting me up and down like I’d set off an alarm at airport security. Shit. He didn’t even hesitate when he got to my crotch. Fuck you, Deeson.

“Remove the phone,” he said, a triumphant sound in his voice.

“I need it, though,” I said, “for… homework. Writing papers. I can’t get behind, it’s my junior year.”

Like somehow “junior year,” that important pre-college-application year, would mean anything to him.

“Remove the phone or I will remove it for you,” Deeson said.

He made me bring it back into the house, watched as I put it back on the counter next to my parents’ phones, then took the key after I locked up again. My parents were sitting on a bench in the van—it had bench seats, like pews in a church, homemade—and I squeezed in next to them, against the side. They gave me a silent, disapproving look. There were others all around us, but no one in the van said a word. Deeson was up front, driving, and as he pulled away from the curb, a panel slid down from the ceiling and closed us all in. It was dark, Ses, darker than the darkest of dark winter nights in your house.

We drove.

We drove, and drove, and drove, and it must have been hours, because I fell asleep against the cold steel wall of the van. I fell asleep and then jerked awake, fell asleep and jerked awake. I had to pee so bad. Deeson was lying when he said the South Compound was close by. The Prophet was lying when he said he’d bought an abandoned building in South Minneapolis. We are nowhere near South Minneapolis. My message on the whiteboard doesn’t make any sense now.

I don’t know where we are.

I don’t know where we are, Sesame.

Have you been to the house yet? Did you figure out right away that the time had come and that I was gone? Did you remember where the fake rock is hidden? Was it covered with snow?

I can’t send you my coordinates, Sesame, because I don’t know where I am.

I screwed up, Ses. Big-time.

I got sucked into something bigger than I ever thought it could be and now I’m stuck. Here in the laundry room. Where I am temporarily “detained.” My attempt to bring the phone was an infraction, which is a thing here, and the laundry room is the punishment. There’s a wire screen near the ceiling, which is low, and it leads into a dark space. Maybe it’s a crawl space. I can’t tell. But it must be close to the outside, because last night when I couldn’t sleep I heard faint sounds from the outside world. Sirens once in a while, police or ambulance, I can’t tell. Every once in a while, the bark of a dog. So I know that the outside world is still there.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books (September 1, 2020)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781534446120

- Ages: 14 - 99

- Lexile ® HL740L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Raves and Reviews

"A thoughtful, realistic story of survival."

– Kirkus Reviews

"Watching two in difficult circumstances teens work through fear and toward bravery is gratifying."

– Publishers Weekly

Awards and Honors

- Minnesota Book Awards Finalist

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Where We Are Hardcover 9781534446120

- Author Photo (jpg): Alison McGhee Photograph (c) Alison McGhee(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit