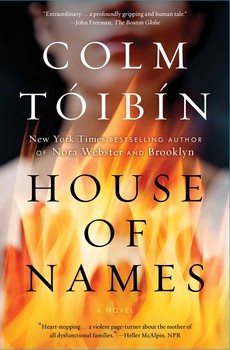

House of Names

A Novel

LIST PRICE $18.00

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

* Named a Best Book of the Year by NPR, The Guardian, The Boston Globe, St. Louis Dispatch

From the thrilling imagination of bestselling, award-winning Colm Tóibín comes a retelling of the story of Clytemnestra and her children—“brilliant…gripping…high drama…made tangible and graphic in Tóibín’s lush prose” (Booklist, starred review).

“I have been acquainted with the smell of death.” So begins Clytemnestra’s tale of her own life in ancient Mycenae, the legendary Greek city from which her husband King Agamemnon left when he set sail with his army for Troy. Clytemnestra rules Mycenae now, along with her new lover Aegisthus, and together they plot the bloody murder of Agamemnon on the day of his return after nine years at war.

Judged, despised, cursed by gods, Clytemnestra reveals the tragic saga that led to these bloody actions: how her husband deceived her eldest daughter Iphigeneia with a promise of marriage to Achilles, only to sacrifice her; how she seduced and collaborated with the prisoner Aegisthus; how Agamemnon came back with a lover himself; and how Clytemnestra finally achieved her vengeance for his stunning betrayal—his quest for victory, greater than his love for his child.

House of Names “is a disturbingly contemporary story of a powerful woman caught between the demands of her ambition and the constraints on her gender…Never before has Tóibín demonstrated such range,” (The Washington Post). He brings a modern sensibility and language to an ancient classic, and gives this extraordinary character new life, so that we not only believe Clytemnestra’s thirst for revenge, but applaud it. Told in four parts, this is a fiercely dramatic portrait of a murderess, who will herself be murdered by her own son, Orestes. It is Orestes’s story, too: his capture by the forces of his mother’s lover Aegisthus, his escape and his exile. And it is the story of the vengeful Electra, who watches over her mother and Aegisthus with cold anger and slow calculation, until, on the return of her brother, she has the fates of both of them in her hands.

Appearances

Bridgehampton Library

Excerpt

I have been acquainted with the smell of death. The sickly, sugary smell that wafted in the wind towards the rooms in this palace. It is easy now for me to feel peaceful and content. I spend my morning looking at the sky and the changing light. The birdsong begins to rise as the world fills with its own pleasures and then, as day wanes, the sound too wanes and fades. I watch as the shadows lengthen. So much has slipped away, but the smell of death lingers. Maybe the smell has entered my body and been welcomed there like an old friend come to visit. The smell of fear and panic. The smell is here like the very air is here; it returns in the same way as light in the morning returns. It is my constant companion; it has put life into my eyes, eyes that grew dull with waiting, but are not dull now, eyes that are alive now with brightness.

I gave orders that the bodies should remain in the open under the sun a day or two until the sweetness gave way to stench. And I liked the flies that came, their little bodies perplexed and brave, buzzing after their feast, upset by the continuing hunger they felt in themselves, a hunger I had come to know too and had come to appreciate.

We are all hungry now. Food merely whets our appetite, it sharpens our teeth; meat makes us ravenous for more meat, as death is ravenous for more death. Murder makes us ravenous, fills the soul with satisfaction that is fierce and then luscious enough to create a taste for further satisfaction.

A knife piercing the soft flesh under the ear, with intimacy and precision, and then moving across the throat as soundlessly as the sun moves across the sky, but with greater speed and zeal, and then his dark blood flowing with the same inevitable hush as dark night falls on familiar things.

*

They cut her hair before they dragged her to the place of sacrifice. My daughter had her hands tied tight behind her back, the skin on the wrists raw with the ropes, and her ankles bound. Her mouth was gagged to stop her cursing her father, her cowardly, two-tongued father. Nonetheless, her muffled screams were heard when she finally realized that her father really did mean to murder her, that he did mean to sacrifice her life for his army. They had cropped her hair with haste and carelessness; one of the women managed to cut into the skin around my daughter’s skull with a rusty blade, and when Iphigenia began her curse, that is when a man tied an old cloth around her mouth so that her words could not be heard. I am proud that she never ceased to struggle, that never once, not for one second, despite the ingratiating speech she had made, did she accept her fate. She did not give up trying to loosen the twine around her ankles or the ropes around her wrists so that she could get away from them. Or stop trying to curse her father so that he would feel the weight of her contempt.

No one is willing now to repeat the words she spoke in the moments before they muffled her voice, but I know what those words were. I taught them to her. They were words I made up to shrivel her father and his followers, with their foolish aims, they were words that announced what would happen to him and those around him once the news spread of how they dragged our daughter, the proud and beautiful Iphigenia, to that place, how they pulled her through the dust to sacrifice her so they might prevail in their war. In that last second as she lived, I am told she screamed aloud so that her voice pierced the hearts of those who heard her.

Her screams as they murdered her were replaced by silence and by scheming when Agamemnon, her father, returned and I fooled him into thinking that I would not retaliate. I waited and I watched for signs, and smiled and opened my arms to him, and I had a table here prepared with food. Food for the fool! I was wearing the special scent that excited him. Scent for the fool!

I was ready as he was not, the hero home in glorious victory, the blood of his daughter on his hands, but his hands washed now as though free of all stain, his hands white, his arms outstretched to embrace his friends, his face all smiles, the great soldier who would soon, he believed, hold up a cup in celebration and put rich food into his mouth. His gaping mouth! Relieved that he was home!

I saw his hands clench in sudden pain, clench in the grim, shocked knowledge that at last it had come to him, and in his own palace, and in the slack time when he was sure he would enjoy the old stone bath and the ease to be found there.

That was what inspired him to go on, he said, the thought that this was waiting for him, healing water and spices and soft, clean clothes and familiar air and sounds. He was like a lion as he laid his muzzle down, his roaring all done, his body limp, and all thought of danger far from his mind.

I smiled and said that, yes, I too had thought of the welcome I would make for him. He had filled my waking life and my dreams, I told him. I had dreamed of him rising all cleansed from the perfumed water of the bath. I told him his bath was being prepared as the food was being cooked, as the table was being laid, and as his friends were gathering. And he must go there now, I said, he must go to the bath. He must bathe, bathe in the relief of being home. Yes, home. That is where the lion came. I knew what to do with the lion once he came home.

*

I had spies to tell me when he would come back. Men lit each fire that gave the news to farther hills where other men lit fires to alert me. It was the fire that brought the news, not the gods. Among the gods now there is no one who offers me assistance or oversees my actions or knows my mind. There is no one among the gods to whom I appeal. I live alone in the shivering, solitary knowledge that the time of the gods has passed.

I am praying to no gods. I am alone among those here because I do not pray and will not pray again. Instead, I will speak in ordinary whispers. I will speak in words that come from the world, and those words will be filled with regret for what has been lost. I will make sounds like prayers, but prayers that have no source and no destination, not even a human one, since my daughter is dead and cannot hear.

I know as no one else knows that the gods are distant, they have other concerns. They care about human desires and antics in the same way that I care about the leaves of a tree. I know the leaves are there, they wither and grow again and wither, as people come and live and then are replaced by others like them. There is nothing I can do to help them or prevent their withering. I do not deal with their desires.

I wish now to stand here and laugh. Hear me tittering and then howling with mirth at the idea that the gods allowed my husband to win his war, that they inspired every plan he worked out and every move he made, that they knew his cloudy moods in the morning and the strange and silly exhilaration he could exude at night, that they listened to his implorings and discussed them in their godly homes, that they watched the murder of my daughter with approval.

The bargain was simple, or so he believed, or so his troops believed. Kill the innocent girl in return for a change in the wind. Take her out of the world, use a knife on her flesh to ensure that she would never again walk into a room or wake in the morning. Deprive the world of her grace. And as a reward, the gods would make the wind blow in her father’s favor on the day he needed wind for his sails. They would hush the wind on the other days when his enemies needed it. The gods would make his men alert and brave and fill his enemies with fear. The gods would strengthen his swords and make them swift and sharp.

When he was alive, he and the men around him believed that the gods followed their fates and cared about them. Each of them. But I will say now that they did not, they do not. Our appeal to the gods is the same as the appeal a star makes in the sky above us before it falls, it is a sound we cannot hear, a sound to which, even if we did hear it, we would be fully indifferent.

The gods have their own unearthly concerns, unimagined by us. They barely know we are alive. For them, if they were to hear of us, we would be like the mild sound of wind in the trees, a distant, unpersistent, rustling sound.

I know that it was not always thus. There was a time when the gods came in the morning to wake us, when they combed our hair and filled our mouths with the sweetness of speech and listened to our desires and tried to fulfill them for us, when they knew our minds and when they could send us signs. Not long ago, within our memories, the crying women could be heard in the night in the time before death came. It was a way of calling the dying home, hastening their flight, softening their wavering journey to the place of rest. My husband was with me in the days before my mother died, and we both heard it, and my mother heard it too and it comforted her that death was ready to lure her with its cries.

That noise has stopped. There is no more crying like the wind. The dead fade in their own time. No one helps them, no one notices except those who have been close to them during their short spell in the world. As they fade from the earth, the gods do not hover over with their haunting, whistling sound. I notice it here, the silence around death. They have departed, the ones who oversaw death. They have gone and they will not be back.

My husband was lucky with the wind, that was all, and lucky his men were brave, and lucky that he prevailed. It could easily have been otherwise. He did not need to sacrifice our daughter to the gods.

My nurse was with me from the time I was born. In her last days, we did not believe that she was dying. I sat with her and we talked. If there had been the slightest sound of wailing, we would have heard. There was nothing, no sound to accompany her towards death. There was silence, or the usual noises from the kitchen, or the barking of dogs. And then she died, then she stopped breathing. It was over for her.

I went out and looked at the sky. And all I had then to help me was the leftover language of prayer. What had once been powerful and added meaning to everything was now desolate, strange, with its own sad, brittle power, with its memory, locked in its rhythms, of a vivid past when our words rose up and found completion. Now our words are trapped in time, they are filled with limits, they are mere distractions; they are as fleeting and monotonous as breath. They keep us alive, and maybe that is something, at least for the moment, for which we should be grateful. There is nothing else.

*

I have had the bodies removed and buried. It is twilight now. I can open the shutters onto the terrace and look at the last golden traces of the sun and the swifts arching in the air, moving like whips against the dense, raked light. As the air thickens, I can see the blurred edge of what is there. This is not a time for sharpness; I no longer want sharpness. I do not need clarity. I need a time like now when each object ceases to be itself and melts towards what is close to it, just as each action I and others have performed ceases to stand alone waiting for someone to come and judge it or record it.

Nothing is stable, no color under this light is still; the shadows grow darker and the things on the earth merge with each other, just as what all of us did merges into one action, and all our cries and gestures merge into one cry, one gesture. In the morning, when the light has been washed by darkness, we will face clarity and singleness again. In the meantime, the place where my memory lives is a shadowy, ambiguous place, comforted by soft, eroding edges, and that is enough for now. I might even sleep. I know that in the fullness of daylight, my memory will sharpen again, become precise, will cut through the things that happened like a dagger whose blade has been whetted for use.

*

There was a woman in one of the dusty villages beyond the river and towards the blue mountains. She was old and difficult but she had powers that had been lost to all others. She did not use her powers idly, I had been told, and most of the time she was not willing to use them at all. In her village she often paid imposters, women old and wizened like herself, women who sat in doorways with their eyes narrowed against the sun. The old woman paid them to stand in for her, to fool visitors into believing that they were the ones with the powers.

We had been watching this woman. Aegisthus, the man who shares my bed and would share this kingdom with me, had learned, with the help of some men who were under his sway, to distinguish between the other women, the decoys, who had no powers at all, and the real one, who could, when she wanted, weave a poison into any fabric.

If anyone wore that fabric they would be rendered frozen, unable to move, and rendered voiceless also, utterly silent. No matter how sudden the shock or severe the pain, they would not have the ability to cry out.

I planned to attack my husband when he returned. I would be waiting for him, all smiles. The gurgling sound he would make when I cut his throat became my obsession.

The old woman was brought here by the guards. I had her locked in one of the inner storerooms, a dry place where grain is kept. Aegisthus, whose powers of persuasion were as highly developed as the old woman’s power to cause death, knew what to say to her.

Both Aegisthus and the old woman were stealthy and wily. But I was clear. I lived in the light. I cast shadows but I did not live in shadow. As I prepared for this, I lived in pure brightness.

What I required was simple. There was a robe made of netting that my husband sometimes used when he came from the bath. I wanted the old woman to stitch threads into it, threads that would have the power to immobilize him once the robe touched his skin. The threads would be as near to invisible as the woman could make them. And Aegisthus warned her that I wanted not only stealth but silence. I wanted no one to hear the cries of Agamemnon as I murdered him. I wanted not a sound to be heard from him.

The woman pretended for some time that she was, in fact, one of the imposters. And even though I allowed no one but Aegisthus to see her and bring her food, she began to divine why she was here, that she had been brought here to help with the murder of Agamemnon, the king, the great, bloodthirsty warrior, victorious in the wars, soon to arrive home. The woman believed that the gods were on his side. She did not wish to interfere with the intentions of the gods.

I had always known that she would be a challenge, but I had come to learn too that it was simpler to work with those who held the old beliefs, who believed that the world was stable.

I arranged therefore to deal with this woman. I had time. Agamemnon was not to return for some days, and I would have warnings when he was approaching. We had spies in his camp by this time, and men on the hills. I left nothing to chance. I planned each step. I had left too much to luck and to the whims and needs of others in the past. I had trusted too many people.

I ordered the poisonous crone we had captured to be brought to one of the windows high in the wall of the corridor outside the room where she was being held. I gave instructions that this malignant creature be hoisted up so that she could peer into the walled garden. I knew what she would see. She would see her own golden granddaughter, the light of her life. We had taken the child from the village. She, too, was our prisoner.

I arranged for Aegisthus to tell the woman that if she wove the poison and if it worked, then she and her granddaughter would immediately be released and allowed home. I ordered him not to finish the next sentence, the one that began, “If you do not . . . ,” but just to look at the woman with such clear intent and malice that she would tremble, or, more likely, make an effort not to show any sign of fear.

Thus it was easy. The weaving took, I was told, a matter of minutes. Although Aegisthus sat with the woman as she worked, he could not find the new threads in the robe when she had finished. When it was done, she merely asked him to be kind to her granddaughter while she was here and to make sure, when they were being returned to the village, that no one saw them or knew who had accompanied them or where they had been. She gazed coldly at him, and he knew from her gaze that the task had been successfully completed and that the lovely, fatal magic would work on Agamemnon.

*

His doom was set in stone when he sent us word that before the battles began he wished to assist at the wedding of one of his daughters, that he wanted around him an aura of love and regeneration to strengthen him and fill his followers with joy before they set out to kill and conquer. Among the young soldiers, he said, was Achilles, the son of Peleus, a man destined to be a greater hero than his father. Achilles was handsome, my husband wrote, and the sky itself would brighten when it saw Achilles pledge himself to our daughter Iphigenia, with his followers watching in awe.

“You must come by chariot,” his message said. “It will take three days. And do not spare anything in your preparations for her wedding. Bring Orestes with you. He is old enough now to savor the sight of soldiers in the days before a battle and to witness the wedding of his sister to a man as noble as Achilles.

“And you must put power in the hands of Electra when you are away, and tell her to remember her father and use power well. The men I have left, the ones too old to fight, will advise her, they will surround her with their care and wisdom until her mother returns with her sister and her brother. She must listen to the elders in the same way her mother does in my absence.

“Then, when we return from war, power will return to its proper source. After triumph, there will be stability. The gods are on our side. I have been assured that the gods are on our side.”

I believed him. I found Iphigenia and told her that she would come with me on a journey to her father’s camp and she would be married to a warrior. I told her that we would have the seamstresses work all day and all night to prepare the clothes for her that we would carry with us. I added my words to the words of Agamemnon. I told my daughter that Achilles, her husband-to-be, was soft-spoken. And I added other words too, words that are bitter to me now, words filled now with shame. That he was brave, admired, and that his charm had not grown rough despite his strength.

I was saying more when Electra came into the room and asked us why we were whispering. I told Electra that Iphigenia, older than she by one year, was to be married, and she smiled and clasped her sister’s hands when I said that word of Iphigenia’s beauty had spread, that it was known about in many places now, and Achilles would be waiting for her, and her father was certain that in times to come there would be stories told of the bride on her wedding day, and of the sky itself bright and the sun high in the sky and the gods smiling and the soldiers in the days before battle made brave and steely by the light of love.

Yes, I said love, I said light, I said the gods, I said bride. I said soldiers steely before battle. I said his name and her name. Iphigenia, Achilles. And then I called in the dressmakers so the work could begin to prepare for my daughter a robe that would match her own radiance, which on the day of her wedding would match the radiance of the sun. And I told Electra that her father trusted her enough to be left here with the elders, that her sharp wit and skill at noticing and remembering made her father proud.

And some weeks later, on a golden morning, with some of our women, we set out.

*

When we arrived, Agamemnon was waiting for us. He came slowly towards us with an expression on his face that I had never seen before. His face, I thought, showed sorrow, but also surprise and relief. Maybe other things too, but they were what I noticed then. Sorrow, I thought, because he had missed us, he had been away a long time, and he was giving away his daughter; and surprise, because he had spent so much time imagining us and now we were here, all flesh, all real, and Orestes, at the age of eight, had grown beyond his father’s dreams as Iphigenia, at sixteen, had blossomed. And he exuded relief, I thought, that we were safe and he was safe and we could be with each other. When he came to embrace me, I felt a pained warmth from him, but when he stood back and surveyed the soldiers who had come with him, I saw the power in him, the power of the leader prepared for battle, his mind on strategy, decisions. Agamemnon, with his men, was an image of pure will. I remember when we married first being carried away by that image of will I saw even more intensely that day.

Also I saw how, unlike other men of his kind, he was ready to listen, as I felt he was now, or would be when I was alone with him.

And then he picked Orestes up and laughed and carried him towards Iphigenia.

He was all charm when he turned to Iphigenia. And it was as if a miracle had occurred when I looked at her, as if some woman had come unbidden onto the earth with an aura of tenderness mixed with reserve, with a distance from common things. Her father moved to embrace her, still holding the boy, and if anyone then had wanted to know what love looked like, if anyone going into battle needed an image of love to take with them to protect them or spur them on, it was here for them, like something precious cut in stone—the father, the son, the daughter, the mother watching fondly, the look of longing on the father’s face with all the mystery of love, and its warmth, its purity, as he gently let his son down to stand beside him so that Agamemnon could hold his daughter in his arms.

I saw it and I am certain of it. In those seconds it was there.

But it was false.

None of us who had traveled, however, guessed the truth for one second, even though some of the others standing around, maybe even most of them, must have known it. But not one of them gave a sign, not a single sign.

The sky remained blue, the sun hot in the sky, and the gods—oh yes, the gods!—seemed to be smiling on our family that day, on the bride-to-be and her young brother, on me, and on her father as he stood in the embrace of love, as he would stand eventually in the victory of battle with his army triumphant. Yes, the gods smiled that day as we came in all innocence to help Agamemnon execute his plan.

*

The day after our arrival, my husband came early to take Orestes with him and have a sword and light body armor made for him so that he would look like a warrior. Women came to see Iphigenia and there was much fuss and wonder as they admired the clothes we had brought with us, and much calling for cool drinks, and much folding and unfolding of garments. After a while, I stood in the space between our quarters and the kitchens listening to the idle chatter there until I heard one of the women mention that some of the soldiers were lingering outside. Among the names she mentioned was Achilles.

How strange, I thought, that he would come so close to our quarters! And then I thought no, it was not strange, he would come to see if he could catch a glimpse of Iphigenia. Of course he would come! How eager he must be to see her!

I walked out into the forecourt and I asked the soldiers which of them was Achilles. He was the tall one, I discovered, who was standing alone. When I approached, he turned and looked at me and I realized something from his gaze, the directness of it, and the tone of his voice as he spoke his name, the honesty in it. This will be the end of our troubles, I thought. Achilles has been sent to us to end what began before I was born, before my husband was born. Some venom in our blood, in all our blood. Old crimes and desires for vengeance. Old murders and memories of murder. Old wars and old treacheries. Old savagery, old attacks, times when men behaved like wolves. It will end now as this man marries my daughter, I thought. I saw the future as a place of plenty. I saw Orestes growing up in the light of this young soldier married to his sister. I saw an end to strife, a time when men would grow old with ease, and battles would become the subject of high talk as night fell and memories faded of the hacked-up bodies and the howling voices rising for miles across some bloodied plain. They could talk of heroes then instead.

When I told Achilles who I was, he smiled and nodded, making clear that he already knew me, and then made to turn away. I called him back and offered him my hand so that he might join his hand with mine as a token of what would soon happen and of the years ahead.

His body appeared to jolt when I spoke, and he looked around, checking if anyone was watching. I understood his reticence and moved some steps away from him before I spoke again.

“Since you are marrying my daughter,” I said, “surely you may touch my hand?”

“Marrying?” he asked. “I am impatient for battle. I do not know your daughter. Your husband—”

“I am sure my husband,” I interrupted, “asked you to maintain distance in these days before the feast, but from my daughter, not from me. In the days to come, all this will change, but if it worries you to be seen speaking to me before your wedding with my daughter, then I must go back to be with the women and away from you.”

I spoke softly. The expression on his face was pained, perplexed.

“You are mistaken,” he said. “I am waiting for battle, not for a bride. There will be no weddings as we wait for the wind to change, as we wait for our boats to stop being hurled against rocks. As we wait for . . .”

He frowned, and then seemed to check himself so that he would not finish what he had begun to say.

“Perhaps my husband,” I said, “has brought my daughter here so that after the battle—”

“After the battle I will go home,” he interrupted. “If I survive the battle, I will go home.”

“My daughter has come here to marry you,” I said. “She was summoned by her father, my husband.”

“You are mistaken,” he said, and once more I saw grace, tempered with firmness and resolve. For a second, I had a vision of the future, a future that Achilles would transform for us, a time to come in a place filled with cushioned corners and nourished shadows, and I would grow old there as Achilles ripened and my daughter Iphigenia became a mother and Orestes grew into wisdom. Suddenly, it occurred to me that in this world of the future I could not see any place for Agamemnon and I could not see Electra either, and I started for a moment, I almost gasped at some dark absence looming. I tried to place both of them in the picture and I failed. I could not see either of them and there was something else that I could not see, as Achilles raised his voice as if to get my attention.

“You are mistaken,” he said again, and then spoke more softly. “Your husband must have told you why your daughter has been summoned here.”

“My husband,” I said, “merely welcomed us when we came. He said nothing else.”

“Do you not know, then?” he asked. “Is it possible you do not know?”

The expression on his face had darkened, his voice had almost broken on the last question.

I hunched over as I moved from him and made my way back to where my daughter and the women were gathered. They barely saw me, since they were marveling over some piece of stitching, holding up a piece of cloth. I sat alone, away from them.

*

I do not know who told Iphigenia that she was not to be married but was to be sacrificed. I do not know who informed her that she was not to have Achilles as her husband, but was rather to have her throat bloodied by a sharp, thin knife in the open air as many spectators, including her own father, gaped at her, and figures appointed for this purpose chanted supplications to the gods.

When the women left, I spoke to Iphigenia; she did not know then. But in the next hour or two, as we waited for Orestes to return, as I lay awake and as she went in and out of the room, someone let her know plainly and precisely. I realized I had fooled myself into believing that there would be some easy explanation for Achilles’ ignorance of the wedding plans. A few times, I had a piercing intimation of the truth, but it seemed so unlikely that anyone intended to harm Iphigenia, since my husband had greeted us in the way he did with his followers around him, and the women from among his camp had come so eagerly to see the clothes.

I went over my conversation with Achilles, thinking back on each word. When Iphigenia came to me, I was certain that I would, by nightfall, receive some news that would soothe me, and that everything would be resolved. I was convinced of this even as she began to speak, as she began to tell me what she had learned.

“Who told you this?” I asked.

“One of the women was sent to tell me.”

“Which of them?”

“I don’t know her. I only know that she was sent to tell me.”

“Sent by whom?”

“By my father,” she replied.

“How can we be sure?” I asked.

“I am sure,” she said.

We sat waiting for Orestes to return, waiting so we could implore whoever came with him to take us to Agamemnon, or allow us to send a message to him saying that he must come and speak to us. Sometimes Iphigenia held my hand, tightening her grip and then letting go, sighing, closing her eyes in dread, and then opening her eyes again to stare vacantly into the distance. Even still it seemed to me as we waited that nothing would happen, that all this was maybe nothing, that the idea of sacrificing Iphigenia to the gods was a rumor spread by the women and that such rumors would be easily spread among nervous soldiers and their followers in the days before a battle.

I wavered from feeling unsure and nervous to sensing that the very worst was to come, as my daughter found my hand again and held it harder and more fiercely. A few times, I wondered if we could flee from here, if we could set out together into the night and make towards home, or some sanctuary, or if I could find someone to take Iphigenia away, disguise her, find a hiding place for her. But I did not know in what direction we could go, and I knew that we would be followed and found. Since he had lured us here, I was sure, Agamemnon was having us watched and guarded.

We sat together in silence for hours. No one came near us. Slowly, I began to feel that we were prisoners and had been prisoners since the moment we arrived. We had been fooled into coming. Agamemnon had realized how excited I would be at the thought of a wedding, and that is the strategy he used to entice us here. Nothing else would have worked.

We heard Orestes’ voice first, calling out in play, and then, to my shock, his father’s. When they both came in, all bright-eyed and boisterous, we stood up to face him. In one second, Agamemnon saw that the woman he had sent had, as he had instructed, told Iphigenia. He bowed his head and then he lifted it and started laughing. He told Orestes to show us the sword that had been forged and polished specially for him, he told him to show us the armor that had been made for him too. He took out his own sword and held it in mock seriousness to challenge Orestes, who, under his father’s careful guidance, crossed swords with him and stood in combat position against him.

“He is a great warrior,” Agamemnon said.

We watched him coldly, impassively. For a moment, I was going to call for Orestes’ nurse and have the boy removed, put to bed, but whatever was going on between Agamemnon and Orestes held me back. It was as if Agamemnon knew that he must play this part of the father with his boy for all it was worth. There was something in the air, or in our expressions, so intense that my husband must have known when he relaxed and faced us that life would change and never be the same again.

Agamemnon did not glance at me now, nor did he look at Iphigenia. The longer his jousting went on, the more I realized that he was afraid of us, or afraid of what he would have to say to us when it stopped. He did not want it to stop. He was, as he continued the game, not a brave man.

I smiled because I knew that this would be the last episode of happiness I would know in my life, and that it was being played out by my husband, in all his weakness, for as long as possible. It was all theatre, all show, the mock sword fight between father and son. I saw how Agamemnon was making it last, keeping Orestes excited without exhausting him, letting him feel that he was showing off his skill and thus making the boy want to do more and more. He was controlling Orestes as we both stood watching.

It struck me for a second that this was what the gods did with us—they distracted us with mock conflicts, with the shout of life, they distracted us also with images of harmony, beauty, love, as they watched distantly, dispassionately, waiting for the moment when it ended, when exhaustion set in. They stood back as we stood back. And when it ended, they shrugged. They no longer cared.

Orestes did not want the mock fight to end, but, within the rules, there was a limit to what they could do. Once, the boy moved too close to his father and left himself fully vulnerable to his father’s sword. As Agamemnon gently pushed him back, it was clear to him that it was a game only and that we had seen this and noted it. This realization quickly made Orestes lose interest and move equally fast into tiredness and irritation. But still he did not want it to end. When I shouted for the nurse, Orestes began to cry. He did not want the nurse, he said, as his father lifted him in his arms and carried him like a piece of firewood towards our sleeping quarters.

Iphigenia did not look at me, nor I at her. We both remained standing. I do not know how much time passed.

When Agamemnon appeared, he walked quickly towards the opening in the tent and then turned.

“So you know, you both know?” he asked quietly.

In disbelief, I nodded.

“There is nothing else to say,” he whispered. “It must be. Please believe me that it must be.”

Before he left us, he gave me a hollow look. He almost shrugged then as he spread out his arms, his palms facing upwards. He was like someone with no power, or he was mimicking for me and for Iphigenia how such a man would seem. Shrunken, easy to fool or persuade.

The great Agamemnon made it plain by his stance that whatever decision had been made, it had been made not by him, but by others. He made it seem that it had been too much for him, all of it, as he darted out into the night to where his guards were waiting.

Then there was silence all around, the silence that can come only when an army sleeps. Iphigenia came to me and I held her. She did not cry or sob. It felt as though she would never move again and we would be discovered like this when morning came.

*

At first light, I walked through the camp in search of Achilles. When I found him, he edged away from me, but as much in pride as in fear, as much for the sake of decorum as nervousness about who was watching us. I drew close to him, but I did not whisper.

“My daughter was tricked into coming here. Your name was used.”

“I too am angry with her father.”

“I will fall at your knees if I need to. Can you help me in my misfortune? Can you help the girl who came here to be your wife? It was for you that we had the seamstresses working day and night. All the excitement was for you. And now she is told that she will be slaughtered. What will men think of you when they hear of this deceit? I have no one else to implore so I implore you. For the sake of your own name, if nothing else, you must help me. Put your hand over mine, and then I will know that we are saved.”

“I will not touch your hand. I will do that only if I have succeeded in changing Agamemnon’s mind. Your husband should not have used my name as though it were a trap.”

“If you do not marry her, if you fail—”

“My name is nothing then. My life is nothing. All weakness, a name used to trap a girl.”

“I can bring my daughter here. Let us both stand in front of you.”

“Let her remain apart. I will speak to your husband.”

“My husband . . .” I began and then stopped.

Achilles looked around at the group of men who were closest to us.

“He is our leader,” he said.

“You will be rewarded if you can prevail,” I said.

He looked at me evenly, holding my gaze until I turned and walked back through the camp alone. Men moved out of my way, out of my sight, as though I, in my efforts to prevent the sacrifice, were some vast pestilence that had been sent to their camp, worse than the wind that had smashed their boats against the rocks and then rose up again in further fury.

When I arrived at our tent, I could hear the sound of Iphigenia crying. The tent was full of women, a few women who had traveled with us, the women who had come the day before, and now some stragglers who added their presence to create an air of mayhem around my daughter. When I shouted at them to get out and they did not attend to me, I pulled one of them by the ear to the opening of the tent and, having ejected her, I moved towards another until all of them, except the women who had traveled with us, began to scatter.

Iphigenia had her hands over her face.

“What has happened?” I asked.

One of the women told us then that three rough-looking men in full armor had come to the tent looking for me. When they were told that I was not there, they believed that I was hiding and ransacked the living quarters, the sleeping quarters and the kitchens. And then they left, taking Orestes with them. Iphigenia began to cry now as the women told me that her brother had been taken. He was kicking and struggling, they said, as they carried him away.

“Who sent these men?” I asked.

There was silence for a moment. No one wished to answer until one of the women eventually spoke.

“Agamemnon,” she said.

I asked two of the women to come with me to the sleeping quarters to prepare my body and my attire. They washed me, adding sweet spices and perfume, and then they helped me to choose my clothes and arrange my hair. They asked me if they should accompany me now, but I thought that I would walk alone through the camp in search of my husband, that I would call out his name, that I would threaten and terrorize anyone I saw who did not help me to find him.

When finally I found his tent, my way was blocked by one of his men, who asked me what business I had with him.

I was in the act of pushing him out of my way when Agamemnon appeared.

“Where is Orestes?” I asked.

“Learning how to use a sword properly,” he replied. “He will be well looked after. There are other boys his age.”

“Why did you send men looking for me?”

“To tell you that it will happen soon. The heifers will be slain first. They are now on their way to the appointed place.”

“And then?”

“And then our daughter.”

“Say her name!”

I did not know that Iphigenia had followed me, and I do not know still how she changed from the sobbing, frightened and inconsolable girl to the poised young woman, her presence solitary and stern, that now came towards us.

“You do not need to say my name,” she interrupted. “I know my name.”

“Look at her. Do you intend to kill her?” I asked Agamemnon.

He did not reply.

“Answer the question,” I said.

“There are many things I must explain,” he said.

“Answer the question first,” I said. “Answer it. And then you can explain.”

“I have learned from your emissary what you intend to do to me,” Iphigenia said. “You do not need to answer anything.”

“Why will you kill her?” I asked. “What prayers will you utter as she dies? What blessings will you ask for yourself when you cut your child’s throat?”

“The gods . . .” he began and stopped.

“Do the gods smile on men who have their daughters killed?” I asked. “And if the wind does not change, will you kill Orestes too? Is that why he is here?”

“Orestes? No!”

“Do you want me to send for Electra?” I asked. “Do you want to find a husband’s name for her and fool her too?”

“Stop!” he said.

As Iphigenia moved towards him, he seemed almost afraid of her.

“I am not eloquent, father,” she said. “All the power I have is in my tears, but I have no tears now either. I have my voice and I have my body and I can kneel and ask that I not be killed before my time. Like you, I think the light of day is sweet. I was the first to call you father, and I was the first you called your daughter. You must remember how you told me that I would in time be happy in my husband’s house, and I asked: Happier than with you, father? And you smiled and shook your head and I curled my head into your chest and held you with my arms. I dreamed that I would receive you into my house when you were old and we would be happy then. I told you that. Do you remember? If you kill me, then that will be a sour dream I had, and surely for you it will bring infinite regret. I have come alone to you, tearless, unready. I have no eloquence. I can only ask you with the simple voice I have to send us home. I ask you to spare me. I ask my father what no daughter should ever have to ask. Father, do not kill me!”

Agamemnon lowered his head as if he were the one who had been condemned. When some of his men approached, he looked at them nervously before he spoke.

“I understand that it calls for pity,” he said. “I love my children. I love my daughter even more now that I see her so composed and in the fullest bloom. But see how large this seagoing army is! It is ready and restive, but the wind will not change for us to attack. Think of the men. Their wives are being abducted by barbarians while they linger here, their land is being laid waste. Each one knows that the gods have been consulted, and each one knows what the gods have ordered me to do. It does not depend on me. I have no choice in this. And if we are defeated, no one will survive. We will all be destroyed, every one of us. If the wind does not change, we will all face death.”

He bowed to some invisible presence in front of him and then he signaled to the two men closest to him to follow him into his tent; two others went to guard the entrance.

It struck me then that if the gods really cared, if they had been watching over us as they were meant to be, they would take pity and quickly change the wind over the sea. I imagined voices coming from the water, from the harbor, then cheering among the men, the flags blowing with this new wind that would allow their ships to move speedily and stealthily so that they would know victory and see that the gods had merely been testing their resolve.

The noises I imagined soon began to give way to shouting as Achilles ran towards us, followed by men roaring abuse at him.

“Agamemnon told me to talk to the soldiers directly myself, to tell them that it was out of his hands,” he said. “I have now spoken to them and they say that she must be killed. They shouted threats at me too.”

“At you?”

“To say that I should be stoned to death.”

“For trying to save my daughter?”

“I begged them. I told them that victory in battle made possible by the murder of a girl was a coward’s victory. My voice was drowned out by their shouting. They will not give in to argument.”

I turned towards the crowd of men that had followed Achilles. I thought that if I could find one face and gaze at it, the face of the weakest among them or the strongest, I could shift my gaze to each of them and make them ashamed. But they would not look up. No matter what I did, not one of them would look up.

“I will do what I can to save her,” Achilles said, but there was in his tone a sound of defeat. He did not name what he could do, or what he might do. I noticed that he too had his eyes cast down. But as Iphigenia began to speak, he looked at her, as did the men around him, who took her in now as though she had already become an icon whose last words would have to be remembered, a figure whose death was going to change the very way the wind blew, whose blood would send an urgent message to the heavens above us.

“My death,” she said, “will rescue all those who are in danger. I will die. It cannot be otherwise. It is not right for me to be in love with life. It is not right for any of us to be in love with life. What is a single life? There are always others. Others like us come and live. Each breath we breathe is followed by another breath, each step by another step, each word by the next one, each presence in the world by another presence. It hardly matters who must die. We will be replaced. I will give myself for the army’s sake, for my father’s sake, for my country’s sake. I will meet my own sacrifice with a smile. Victory in battle will be my victory then. The memory of my name will last longer than the lives of many men.”

As she spoke, her father and his men slowly emerged from his tent, and others gathered who had been nearby. I watched her, unsure all the time if this was a ploy, if her soft tone and her voice low with humility and resignation, but loud enough that it could be heard, was something she had planned so that she could somehow save herself.

No one moved. There was no sound from the camp. Her words lay on the stillness of air like a further stillness. I noticed Achilles about to speak and then deciding to remain silent. Agamemnon in those moments attempted to assume the pose of a commander, as he ran his eyes over the far horizon, suggesting that large questions were on his mind. No matter what he did, however, he appeared to me like a diminished, aging man. He would, in the future, I thought, be viewed with contempt for luring his daughter to the camp and having her murdered to appease the gods. He was still feared, I saw, but I could see too that this would not last.

Thus he was at his most dangerous, like a bull with a sword stuck into its side.

With dignity and proud scorn, I walked away from them, with Iphigenia gently following. I was sure then that the weak leader and the angry, uneasy mob would hold sway. I knew that we had been defeated. Iphigenia continued speaking, asking me not to mourn her death, and not to pity her, asking me to tell Electra how she died and to implore Electra not to wear mourning clothes for her, and to use my energy now to save Orestes from the poison that was all around us.

*

In the distance, we could hear the howls of the animals that had been brought to the place of sacrifice. I demanded that all the women who once more had arrived get out of our sight, except the few we trusted who had accompanied us to the camp. I ordered Iphigenia’s wedding clothes to be prepared and the clothes that I had planned to wear at the wedding ceremony to be laid out for me. I asked for water so we both could bathe and then special white ointment for our faces and black lines for around our eyes so that we would seem pale and unearthly as we made our way to that place of death.

At first no one spoke. Then the silence was broken at intervals by men shouting, by the sound of prayers rising, by animals bellowing and letting out fierce shrieks.

When word came that there were men outside and they were preparing to enter, I went towards the opening of the tent. The men seemed frightened when they saw me.

“Do you know who I am?” I asked.

They would not look at me or reply.

“Are you too cowardly to speak?” I asked.

“We are not,” one of them said.

“Do you know who I am?” I asked this man.

“Yes,” he said.

“From my mother I received a set of words that she, in turn, had received from hers,” I said. “These words have been sparingly used. They cause the insides of all men within earshot to shrivel, and then the insides of all their children. Only their wives are spared, and they are destined then to search the dust for food to peck.”

They were so filled with superstition, I saw, that any set of words that invoked the gods or an ancient curse would instill instant fear in them. Not one of them questioned me even with a glance, not one shadow passed over what I had said, not one hint that there was no such curse, and never had been.

“If one of you lays a finger on my daughter or on me,” I continued, “if one of you walks ahead of us, or speaks, I will invoke that curse. Unless you come behind us like a pack of dogs, I will speak the words of the curse.”

Each one of them looked chastened. Arguments would not work for them, not even pity, but the slightest invocation of a power beyond their power had them spellbound. Had they looked up again, they would have seen a smile of pure contempt pass across my face.

Inside, Iphigenia was ready, like some deeply molded version of herself, stately, placid, not responding to the sound of an animal howling in pain that rose at the very place where she soon would see light for the last time.

I whispered to her: “They are frightened of our curses. Wait until there is silence and raise your voice. Explain how ancient the curse is, passed from mother to daughter over time, and how seldom it has been used because of its power. Threaten to invoke it unless they relent, threaten it first against your father and then against each one of them, beginning with those closest to you. Warn them that there will be no army left at all, just dogs growling in the deathly stillness that your curse will leave behind.”

I told her then what the words of the curse should say. We walked in ceremony from our tent to the killing place, Iphigenia first, with me some distance behind her, and then the women who had come with us, and then the soldiers. The day was hot; the smell of the blood and the innards of animals and the aftermath of fear and butchering came towards us until it took all our will not to cover our noses from the stench. Instead of a place of dignity, they had made the place where the killing was to happen into a ramshackle site, with soldiers wandering around aimlessly, and the leftover parts of dead animals strewn about.

Perhaps it was this scene, coupled with how easy it had been to invoke the gods in the curse that I had invented, that sharpened something already in me. As we walked towards the place of slaughter, I realized for the first time that I was sure, fully sure, that I did not believe at all in the power of the gods. I wondered if I was alone in this. I wondered if Agamemnon and the men around him really cared about the gods, if they really believed that a hidden power beyond their power was holding the troops in a spell that no mortal power could manage to cast.

But of course they did. Of course they were sure of what they believed, enough for them to want to go through with this plan.

As we approached Agamemnon, he whispered to his daughter: “Your name will be remembered forever.”

He turned to me and in a voice of gravity and self-importance he whispered: “Her name will be remembered forever.”

I saw now that one of the soldiers who had accompanied us went to Agamemnon and whispered something to him. Agamemnon listened closely and then spoke quietly, firmly, to the five or six men around him.

Then the chanting began, the calling out to the gods in phrases filled with repetitions and strange inversions. I closed my eyes and listened. I could smell the blood of the animals as it began to sour, and there were vultures in the sky, so it was all death, and then the single sound of the chant followed by the rippling, rising sound of the chant being repeated by those who followed the gods most closely and then a sudden mass sound directed towards the sky as thousands of men responded with one voice.

I looked at Iphigenia as she stood alone. She exuded an unearthly power, with the beauty of her robes, the whiteness of her face, the blackness of her hair, the black lines around her eyes, her stillness and silence.

At that moment, the knife was produced. Two women walked towards Iphigenia and loosened her hair from its pins, then pushed down her head and hurriedly, roughly cut her hair. When one of them cut into her skin and Iphigenia cried out, however, the cry was that of a girl, not a sacrificial victim, but a young, fearful, vulnerable girl. And the sacred spell was broken for a moment. I knew how fragile this crowd was. Men began to shout. Agamemnon looked around him in dismay. I knew as I watched him how thin his control was.

As Iphigenia pulled herself loose and began to speak, no one could hear her at first and she had to scream to get silence. When it was clear that she was ready to invoke a curse against her father, a man came from behind her with an old white cloth and bound it around her mouth and dragged her, as she kicked and used her elbows, to the place of sacrifice, where he tied her hands and her feet.

I did not hesitate then. I stretched out my arms and raised my voice and I began the curse of which I had warned them. I directed it against all of them. Some of those in front of me started to run in fright, but from behind another man came with a ragged cloth that, despite my efforts, he pulled tight around my mouth too. I was dragged away as well, but in the opposite direction, away from the place of sacrifice.

When I was out of sight, out of earshot, I was kicked and beaten. And then at the edge of the camp, I saw them lifting a stone. It took three or four men to lift it. The men who had dragged me pushed me into a space dug into the earth below the stone.

The space was large enough to sit in but not to stand up or lie down in. Once they had me there, they quickly put the stone back over the opening. My hands were not bound, so I could move them enough to take the cloth from my mouth, but the stone was too heavy for me to push, so I could not release myself. I was trapped; even the urgent sounds I made seemed trapped.

I was half-buried underground as my daughter died alone. I never saw her body and I did not hear her cries or call out to her. But others told me of her cry. And those last high sounds she made, I now believe, in all their helplessness and fear, as they became shrieks, as they pierced the ears of the crowd assembled, will be remembered forever. Nothing else.

*

Soon, for me, the pain began, the pain in my back that came from being cramped under the ground. The numbness in my arms and legs soon became painful too. The base of my spine began to be irritated and then felt as if it were on fire. I would have given anything to stretch my body, let my arms and legs loose, stand up straight and move. That was all I thought about for the first while.

Then the thirst began, and the fear that seemed to make the thirst even more intense. All I thought about now was water, even the smallest amount of water. I remembered times in my life when there had been pitchers of cool drinking water close to me. I imagined springs in the earth, deep wells. I regretted that I had not savored water more. The hunger that came later was nothing to this thirst.

Despite the vileness of the smell, and the ants and spiders that crawled around me, despite the pain in my back and in my arms and legs, despite the hunger that deepened, despite the fear that I would never come out of here alive, it was the thirst that turned me, changed me.

I had, I realized, made one mistake. I should not have threatened with a curse the men who came to accompany us to the place of death. I should have let them do as they willed, walk ahead of us, or alongside as though Iphigenia were their prisoner. That soldier who had spoken to my husband had, I was sure, whispered him a warning. He had prepared him and now, during my time underground, I blamed myself. As a result of my words, spoken too hastily, I was certain that Agamemnon had ordered that if we began a curse, my daughter or I, we were to be silenced instantly by the gagging cloth.

If he had not been prepared, I imagined the men scattering in fear as Iphigenia began to curse them. I imagined her threatening to continue the curse, to finish the string of words that would shrivel them, unless they released her. I imagined that she could have been saved.

I was at fault. In that time under the earth, in order to distract myself from the thirst, I resolved that if I were spared I would weigh each word I spoke and decision I made. In the future, I would weigh the smallest action.

Because of how roughly the stone had been put over me, I could see a sliver of light, so that when it faded and I could see nothing I knew it was night. Through those hours of darkness, I went over everything from the start. We should never have been fooled into coming here. And we should have worked out a way of fleeing once Agamemnon’s intentions became clear. Such thoughts made the thirst that I suffered even more intense. That thirst lived in me like something that could never be assuaged.

The following morning, when someone threw a pitcher of water into the hole where they had buried me, I heard laughter. I tried to drink what water I could that had soaked into my clothes, but it was almost nothing. The water had merely wet me and the ground beneath me. It had also let me know, in case I needed to know, that I was not forgotten. At intervals over the next two days, they threw more water in. It mixed with my excrement to make a smell like that of a body as it putrefies. It was a smell that I thought would never leave me.

What stayed with me besides that smell was a thought. It began as nothing, as a piece of bad temper arising from the pure discomfort and the thirst, but then it grew and it came to mean more than any other thought or any other thing. If the gods did not watch over us, I wondered, then how should we know what to do? Who else would tell us what to do? I realized then that no one would tell us, no one at all, no one would tell me what should be done in the future or what should not be done. In the future, I would be the one to decide what to do, not the gods.

And in that time I determined that I would kill Agamemnon in retaliation for what he had done. I would consult no oracle or priest. I would pray to no one. I would plot alone in silence. I would be ready. And this would be something that Agamemnon and those around him, so filled with the view that we all must wait for the oracle, would never guess, never suspect.

*

On the third morning, close to first light, when they lifted the stone, I was too stiff to move. They tried to pull me out by the arms, but I was locked into the narrow space where they had buried me. They had to lever me out slowly; they put their strength under my arms because I could not stand, the power in my legs had gone. I saw no value in speech, and did not smile in satisfaction as they held their noses against the stench that rose in the morning sun from the hole where they had held me.

They took me to where the women were waiting. For hours that morning, having washed me and found me fresh clothes, they fed me and I drank. No one spoke. They were afraid, I saw, that I was going to ask them about the last moments of my daughter’s life and the disposal of her body.

I was ready to be left in peace by them so that I could sleep, when we heard the sound of running and voices. One of the men who had accompanied us to the place of death came breathlessly into the tent.

“The wind has changed,” he said.

“Where is Orestes?” I asked him.

He shrugged and ran back out into the crowd. A sound rose then, the noise of instructions and commands. Within a short time, two soldiers came into the women’s tent and stood guard close to the entrance; they were followed soon by my husband, who had to bend as he pushed through to us, because he was carrying Orestes on his shoulders. Orestes had his small sword in his hand; he was laughing as his father made as though to unseat him.

“He will be a great warrior,” he said. “Orestes is the chief of men.”

When he let him down, Agamemnon smiled.

“We will sail tonight when the moon sets. You will take Orestes and your women home and wait for me. I will give you four men to guard you on your way.”

“I don’t want four men,” I said.

“You will need them.”

As he stepped backwards, Orestes realized that he was being left with us. He began to cry. His father lifted him and handed him to me.

“Wait for me, both of you. I will come when the task is done.”

He stalked out of the tent. Soon, four men came, men whom I had threatened with my curse. They told us that they wanted to begin our journey before nightfall. They appeared afraid of me as I told them that it would take us time to prepare. I suggested that they stand outside the tent until I called them.

One of them was softer, younger than the others. He took control of Orestes and distracted him with games and stories as we made our way home. Orestes was filled with life. He would not let his sword out of his hand as he spoke of warriors and battles and how he would follow his enemy until the end of time. It was only in the hour before sleep that he would whimper, moving towards me for warmth and comfort and then pushing me away as he started to cry. His dreams woke us on some of those nights. He wanted his father and then his sister and then the friends he had made among the soldiers. He wanted me too, but when I held him and whispered to him, he recoiled in fright. Thus our journey was filled both day and night with Orestes, so much so that we did not think about what we would say when we arrived home.

All of the others must have wondered, as I did, if word of the fate of Iphigenia had reached Electra, or reached the elders who had been left to advise her. On the last night of our journey, I concentrated on keeping Orestes calm under a high, starry sky as I started to think about what I would do now, how I would live and whom I might trust.

I would trust no one, I thought. I would trust no one. That was the most useful thing to hold in my mind.

*

In the weeks we had been away, Electra had heard rumors, and the rumors had aged her and made her voice shrill, or more shrill than I had remembered it. She ran towards me for news. I know now that not concentrating on her and her alone was my first mistake with her. The isolation and the waiting seemed to have unhinged some part of her so it was hard to make her listen. Maybe I should have stayed up through the night taking her into my confidence, telling her what had happened to us step by step, minute by minute, and asking her to hold me and comfort me. But my legs still hurt and it was hard to walk. I was still ravenous for food and no amount of water quenched my thirst. I wanted to sleep.

I should not have brushed her aside, however. Of that I am sure. I was dreaming of fresh clothes, my old bed, a bath, food, a pitcher of sweet water from the palace well. I was dreaming of peace, at least until Agamemnon returned. I was making plans. I left the others to tell her the story of her sister’s death. I moved like a hungry ghost through the rooms of the palace away from her, away from her voice, a voice that would come to follow me more than any other voice.

*

When I woke on the first morning, I realized that I was a prisoner. The four men had been sent to guard me, to watch over Electra and Orestes, to ensure the loyalty of the elders to Agamemnon. They were happy once I was in my chambers, once I asked for nothing more than food and drink and time to sleep and to walk in the garden and restore the power in my legs. If I left my own quarters, two of them followed me. They let no one see me except the women who took care of me and they questioned those women each night about what I said and did.

It occurred to me that I would have to murder all four of them on a single night. Nothing could happen until that was done. When I was not sleeping, I was planning how best this could be carried out.

Even though the women brought me news, I could not be sure of them. I could be sure of no one.

Electra continued to run through the palace, unsettling the very air. She developed a habit of repeating the same lines to me, the same accusations. “You let her be sacrificed. You came back without her.” I, in turn, continued to ignore her. I should have made her see that her father was not the brave man she still believed him to be, but rather a weasel among men. I should have made her see that it was his weakness that caused the death of her sister.

I should have had her join me in my rage. Instead, I left her free to have her own rage, much of it now directed against me.

When she came to my room, I often feigned sleep, or turned away from her. She had many things to say to the elders and to the four men her father had sent. They, I saw, grew weary of her too.

But one day, I began to listen to her carefully, as she seemed more agitated than usual.

“Aegisthus,” she said, “is walking these corridors in the night. He is appearing in my room. Some nights when I wake, he is standing at the foot of my bed smiling at me and then he retreats into the shadows.”

Aegisthus was being held hostage; he had been in the dungeon under our care, as my husband phrased it, for more than five years. It was agreed that he must be well fed and not harmed, since he was a glittering prize, clever and handsome and ruthless, I was told, with many followers in the outreaches, the wild places.

When our armies had first taken Aegisthus’ family stronghold, no one could fathom how two of my husband’s guards were found each morning lying in their own blood. Some felt that it was a curse. Guards were detailed to guard the guards. Spies were positioned to watch through the night. But still, each morning, once first light came, two guards were found lying facedown in their blood. It was soon believed that Aegisthus was the killer, and this was confirmed when he was taken hostage, as no more guards were found dead. His followers offered to pay ransom, but my husband saw that, so great was Aegisthus’ standing, holding him here, keeping him in chains, was more powerful than sending an army to put down his followers, who had fled into the hills.

When he met with his advisers, my husband often asked, amused, if there was any word of unruliness in the conquered territories and then, on hearing that all was well, he would smile and say: “As long as we keep Aegisthus here, all will be at peace. Make sure that his chains are firmly in place. Have him checked each day.”

There was talk of our prisoner as the years passed, of his good manners and his good looks. Some of the women who served me spoke of how he had tamed the birds that flew through the high window of his cell. One of the women whispered too that Aegisthus knew how to attract young women into his cell, and indeed young servant boys. One day when I asked my women why they were trying to suppress their laughter, they finally explained that one of them had heard the sound of the clanking of chains echoing from Aegisthus’ cell and had stood outside until one of the serving boys had emerged with a furtive, sheepish look and had fled back into the kitchen to resume his duties there.

There was also something that my mother had told me at the time of my marriage. There was, she said, a story that my father-in-law in the heat of rage had ordered Aegisthus’ two half brothers killed and then stuffed and cooked with spices and served to their father at a feast. This stayed in my mind now as I thought about our prisoner. He might have his own reasons to wish to take revenge on my husband were he given the chance.

When Electra mentioned again that she had seen the prisoner standing in her room, I told her that she was dreaming. She insisted that she was not.

“He woke me from my sleep. He whispered words I could not hear. He disappeared before I could call the guards. When the guards came, they swore that no one had passed them, but they were mistaken. Aegisthus moves through the palace at night. Ask your women, if you do not believe me.”

I told her that I did not want to hear of this again.

“You will hear of it each time it happens,” she said defiantly.

“You sound as though you want him to appear,” I said.

“I want my father to return,” she said. “Not until then will I feel safe.”

I was about to tell her that her father’s interest in the safety of his daughters was not something that could be so confidently invoked, but instead I questioned her further about Aegisthus. I asked her to describe him.

“He is not tall. He lifts his face and smiles when I awake, as though he knows me. His face is the face of a boy, and his body too is boyish.”

“He has been a prisoner for many years. He is a murderer,” I said.

“The figure I saw,” she replied, “is the same figure that the women describe who have seen him chained in his cell.”

I began to sleep early so that I would wake when it was still dark. I noticed the soundlessness around me. The guards outside my door were sleeping. Some nights I practiced moving from room to room in bare feet, hardly breathing. Not going far. The only sounds I heard were men snoring in one of the rooms in the distance. I liked the sound because it meant that the noise I made was nothing, a noise that could not be easily heard.

I had a plan now, and the plan involved finding Aegisthus and seeking his support.

After a week or more, I risked traveling into the bowels of this building. I would feign sleepwalking, I thought, if anyone found me. I could not work out, however, where exactly Aegisthus was held, in a dungeon floor below the one where the kitchens and storerooms were or in some outer dungeon.

I started to haunt the corridors in the hard hours of night when it was silent. And it was on one of those nights that I came across our hostage face-to-face. He was as young and boyish as Electra had described, with no hint that he had been in a dungeon for many years.

“I have been looking for you,” I whispered.

He was not frightened or ready to turn and run. He examined me with equanimity.

“You are the woman whose daughter was sacrificed,” he said. “You were buried in a hole. You have been walking in these corridors. I have been watching you.”

“If you betray me,” I replied, “you will be found dead by the guards.”

“What do you want? You must be direct,” he said. “If you do not use me, perhaps someone else will.”

“I will have guards put at your door all night.”

“Guards?” he asked and smiled. “I know the ones who matter. Nothing escapes me. Now what do you want?”

I had one second to decide, but I knew as I spoke that I had decided some time before. I was ready now.

“The four men,” I said, “who came with us from the camp, I want them killed. I can guide you to where they sleep. They have guards at their door, but the guards sleep at night.”

“All four killed on the same night?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And in return?”

“Everything,” I said, and put a finger to my lips and moved back as quietly as I could to my quarters.

Nothing happened then. I realized that perhaps I had risked too much, but I knew that I would have to risk even more were anything to happen. I watched the four guards. I watched the elders who had been left here when my husband went to war. I listened carefully to the murmurings and gossip of the women. I used Orestes as an excuse to wander beyond my own quarters. I followed his sword fights with one of the guards and his young son who often accompanied his father. I knew in this strange time as rumors came of how our army had prevailed that something would move or shift, that somebody would give me a sign, even unwittingly, a sign that would help me, a sign before official news would come to me of Agamemnon’s victorious return.

Each night, I made my soundless journeys in the corridors and then I returned and slept, often sleeping beyond the dawn until Orestes came to my side, all energy still, all talk of his father and the soldiers and the swords. On one of those nights, having fallen into the deepest sleep, I was woken by the sound of an owl screaming at my window and then by some other sound. I lay listening, hearing footsteps from outside my door and voices and shouts to the guards that they must protect me with their lives.

When I approached the door, they would not let me leave my room, or allow anyone to enter. Louder sounds then began, men shouting orders, and others running and the high-pitched voice of Electra. Then Orestes was rushed into my room by two men.

“What has happened?” I asked.

“The four men who came with you were found in their own blood, murdered by their guards,” one of the men said.

“Their guards?”

“Do not worry. The guards have been dispatched.”

I looked out and saw the bodies being carried along the corridor outside and then I returned to the room and spoke softly to Orestes to distract him. When Electra came, I signaled to her not to speak of what had occurred in her brother’s presence. Soon she tired of having to be silent and left me and my son in peace. When she returned, she whispered to me that she had spoken to the elders, who had assured her that this had been a feud over cards or dice between the guards and the four men. They had been drinking.

“The guards’ faces were all badged with blood,” she said, “and so were their daggers. They must have been drunk. They will do no more drinking now, no more killing either.”

It was nothing more than a feud between men, Electra added, and would seem nothing to her father when he returned. She had issued an order in my name against any dice or card games. All drinking would be banned too, she said, until Agamemnon returned.

I moved with Orestes into the open air. I spoke to him gently as we went in search of a soldier who would train him further in the art of sword fighting.

It was too dangerous, I thought, to venture far in the corridors at night. In the dark hours, I stayed by my door, watching, listening for the slightest sound.

One night, when Aegisthus appeared as I knew he would, like a fox following a trail, he beckoned me to a chamber where there was no one.

“I have men under my control,” he whispered. “We are now ready. We can do anything.”

“Go to the house of each of the elders my husband left to govern,” I whispered. “Take a child. A son or a grandson. Your men must explain that I gave orders for this and that if they want the child returned they must appeal to me. Take the children some distance away. Do not harm them. Keep them safe.”

He smiled.

“Are you sure?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said and moved silently away from him and back to my chamber.

Nothing happened for some days. More rumors came of Agamemnon’s victories and of the enormous spoils he was conveying back to the palace. The elders came to consult with me when it was clear that Agamemnon would return once some further territories were under his control.

“We must prepare a fitting welcome for him,” they said, and I bowed and nodded and asked their permission to call Orestes into the room, and Electra, so that they might hear of their father’s glory, so that they too might prepare themselves for his return. Orestes came in solemnly with his sword by his side. He listened as a man might listen, not smiling but mimicking the gestures of a man. Electra asked that she might greet her father before I did, or the elders did, since she had been the one who had remained, who had ensured that her father’s rule prevailed while I was away. This was agreed. I bowed.

A few days later, some women came to my quarters in the hours after dawn to say that the elders wished to see me, that they had gathered one by one as the light came up and they seemed agitated. Some, indeed, had wanted to visit me in my room, only to be informed that I was sleeping and could not be disturbed. I sent a woman to find Orestes so that he would not come looking for me and asked her to accompany him to the garden. I dressed carefully and slowly. It would be better, I thought, if the men were left to wait.