LIST PRICE $7.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

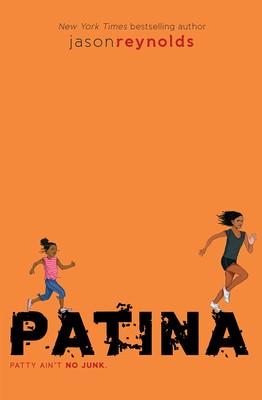

A newbie to the track team, Patina must learn to rely on her teammates as she tries to outrun her personal demons in this New York Times bestselling follow-up to the National Book Award finalist Ghost by New York Times bestselling author Jason Reynolds.

Ghost. Lu. Patina. Sunny. Four kids from wildly different backgrounds with personalities that are explosive when they clash. But they are also four kids chosen for an elite middle school track team—a team that could qualify them for the Junior Olympics if they can get their acts together. They all have a lot to lose, but they also have a lot to prove, not only to each other, but to themselves.

Patina, or Patty, runs like a flash. She runs for many reasons—to escape the taunts from the kids at the fancy-schmancy new school she’s been sent to ever since she and her little sister had to stop living with their mom. She runs from the reason WHY she’s not able to live with her “real” mom anymore: her mom has The Sugar, and Patty is terrified that the disease that took her mom’s legs will one day take her away forever. And so Patty’s also running for her mom, who can’t. But can you ever really run away from any of this?

As the stress builds, it’s building up a pretty bad attitude as well. Coach won’t tolerate bad attitude. No day, no way. And now he wants Patty to run relay…where you have to depend on other people? How’s she going to do THAT?

Ghost. Lu. Patina. Sunny. Four kids from wildly different backgrounds with personalities that are explosive when they clash. But they are also four kids chosen for an elite middle school track team—a team that could qualify them for the Junior Olympics if they can get their acts together. They all have a lot to lose, but they also have a lot to prove, not only to each other, but to themselves.

Patina, or Patty, runs like a flash. She runs for many reasons—to escape the taunts from the kids at the fancy-schmancy new school she’s been sent to ever since she and her little sister had to stop living with their mom. She runs from the reason WHY she’s not able to live with her “real” mom anymore: her mom has The Sugar, and Patty is terrified that the disease that took her mom’s legs will one day take her away forever. And so Patty’s also running for her mom, who can’t. But can you ever really run away from any of this?

As the stress builds, it’s building up a pretty bad attitude as well. Coach won’t tolerate bad attitude. No day, no way. And now he wants Patty to run relay…where you have to depend on other people? How’s she going to do THAT?

Excerpt

Chapter 1 1

TO DO: Everything (including forgetting about the race and braiding my sister’s hair)

AIN’T NO SUCH thing as a false start. Because false means fake, and ain’t no fake starts in track. Either you start or you don’t. Either you run or you don’t. No in-between. Now, there can be a wrong start. That makes more sense to me. Means you just start at the wrong time. Just jump early and break out running with no one there running with you. No competition except for your own brain that swears there’s other people on your heels. But ain’t nobody there. Not for real. Ain’t no chaser. That’s what they really mean when they say false start. A real start at the wrong time. And at the first meet of the season, nobody knew this more than Ghost.

Before the race, me and everybody else stood on the sidelines, clapping and hyping Ghost and Lu up as they took their marks. This was of course after they had already gassed each other up, talking to each other like there was no one else on the track but them. Funny how they went from mean-muggin’ each other when they first met, to becoming all buddy-buddy like they their own two-man gang or something. Lu and Ghost—sticking together like glue. Ha! Glue! Ghost and Lu, Glue. Get it? That could be their corny crew name. Lost would also work. Matter fact, there was a moment where I thought that name might even be more fitting. Especially after what Ghost did.

See, at first, I thought he’d timed it perfectly. I thought Ghost pushed off from the line at the exact moment the gun went off, as if he just knew when it was coming. Like he could feel it on the inside of him or something. But he didn’t hear the second shot. Well, I take that back. Of course he heard it. It was a loud boom. It was impossible not to hear it. But he didn’t know it meant that he’d jumped too early, that he’d false started. I mean, this was his first race, so he had no clue that that second shot meant to stop running, and start over. So… he didn’t.

He ran the entire hundred meters. Didn’t know that people weren’t cheering him on, but were yelling for him to pull up, to go back to the starting line. So when he got to the finish line, he threw his hands up in victory and turned around with one of them million-toothed smiles until he noticed all the other runners—his competition—were still up at the top of the track. He looked out into the crowd. Everybody, laughing. Pointing. Shaking their heads, while Ghost dropped his. Stared at the black tar, his chest like someone blowing up a balloon inside him, then letting the air out, then blowing it back up, then letting the air out. I was afraid that balloon was gonna bust. That Ghost would burst open like he used to do when he first joined the team. And I could tell by the way he was chewing on the side of his jaw that he wanted to, or maybe just keep running, off the track, out of the park, all the way home.

Coach walked over to him, whispered something in his ear. I don’t know what it was. But it was probably something like, “It’s okay, it’s okay, settle down, you’re still in it. But if you do it again, you’re disqualified.” Nah, knowing Coach, it was probably something a little more deep, like… I don’t know. I can’t even think of nothing right now, but Coach was full of deep. Whatever it was, Ghost lifted his head and trotted back to the line, where Lu was waiting with his hand out for a five. Ghost was still out of breath, but there was no time for him to catch it. He had to get back down on his mark. Get ready to run it all over.

The starter held the gun in the air again. My stomach flipped over again. The man pulled the trigger again. Boom! again. And Ghost took off. Again. It was almost like his legs were sticks of dynamite, and the first run was just the fuse being lit, and now, the tiny fire had gotten to the blowup part. And let me tell you, Ghost… blew up. Busted wide open in the best way. I mean, the dude exploded down the line in a blur, even faster this time, his silver shoes like sparks flicking up off the track.

First race. First place.

Even after a false start.

And if a false start means a real start at the wrong time—the wrong time being too early—then I must’ve had a false finish, which also ain’t a fake finish, but a real finish, just… too late. Make sense?

Just in case it don’t, let me explain.

My race was up next. And here’s the thing, I’ve been running the eight hundred for three years straight. It’s my race. I have a system, a way of running it. I come off the block strong and low and by the time I’m straight up, my stride is steady, but I always allow myself to drop back a little. You know, keeping it cool for the first lap. Pace. That’s where eight-hundred runners blow it. They start out too fast and be rigged by the second lap. I seen a lot of girls get roasted out there, showboatin’ on that first four hundred. But I knew better. I knew the second four hundred was the kicker. What I didn’t know, though, was just how fast the girls in this new league were. What kinda shape they were in. So when the gun blew, and we took off, I realized that the pace I had to keep just to stay with the pack was faster than I was used to. But, of course, I’m thinking, these girls are stupid and are gonna be tired in twenty seconds.

In thirty seconds.

In forty seconds.

Never happened, and instead it ended up being me saying to myself, Oh God, I’m tired. How am I tired? And as we rounded into the final two hundred meters, I had to dig deep and step it up. So I turned on the jets.

Here’s how it went.

Cornrows, Low-Cut, Ponytail, and Puny-Tail in front of me. Chop ’em down, Patty. Push, push, push, breathe. Cornrows is on my side now. The crowd is screaming the traditional chant when someone is getting passed—Woooop! Woooop! Woooop! Push. Push. Cornrows is toast. One hundred meters to go. Mouth wide open. Eyes wide open. Stride wide open. Chop ’em down, Patty. Arms pumping, whipping the air out of my way like water. Low-Cut is slowing up. Her little pea-head’s bobbling like it could snap right off. She’s tired. Finally. Woooop! Woooop! Got her. Two more to go. Ponytail can feel me coming. She can probably hear my footsteps over the screaming crowd. She knows I’m close, and then she makes the biggest mistake ever—the one thing every coach tells you to never do—she looked back. See, when you look back, it automatically knocks your stride off and it gets you messed up mentally. And once Ponytail looked over her shoulder, the woooops started back up like a siren. Woooop! Woooop! Woooop! Fifty meters. That’s right, I’m coming. Chop ’em down, Patty. I’m coming. I could see Puny-Tail just ahead of her, that little twist of hair in the back of her head like a snake tongue. She was running out of breath. I could see that by the way her form had broken down. Ponytail was too. We all were. And even worse for me, we were also running out of track.

I got Ponytail by a nose—second place—then collapsed, people cheering all around me, jumping up and down in the stands quickly becoming a wavy blur of color as the tears rose. Second? Stupid second place? Ugh. No way was I going to cry. Trust me, I wanted to, water pricking at my eyelids, but no way. I wanted to kick something, I was so mad! Coach Whit came over and helped me up, and once I was standing, I yanked away from her and limped over to the bench. My legs were burning and cramping, but I wanted to kick something anyway. Maybe kick the bench over. Kick those stupid orange slices Lu’s mother brought. Anything. But instead I just sat down and didn’t say a word for the rest of the meet. Yes, I’m a sore loser, if that’s what you wanna call it. To me, I just like to win. I only wanna win. Anything else is… false. Fake.

But real.

So real, I didn’t even want to talk about it on the way to church the next day. Not with no one. Not even with God. I’d spent all morning braiding Maddy’s hair the same way Ma used to braid mine when I was little. Only difference is Ma got fat fingers, and used to be braiding like she was trying to strip my edges or make me bald. Talkin’ ’bout, “Gotta make it tight so it don’t come loose.” Right. But I don’t even do Maddy’s that tight, and I can knock out a whole head full of hair in half an hour if she sits still. Which she never does.

“How many more?” Maddy whined, squirming on the floor in front of me.

“I’m almost done. Just chill out, so I can…” I picked up the can of beads and shook them in her ear like one of them Spanish shaker things. And just like that, she calmed down and let me tilt her head forward so I could braid the last section, the bit of curls tightly wound at the base of her neck. I dipped my finger in the gunk on the back of my hand, then massaged it into Maddy’s scalp. Then I stroked grease into the leftover bush-ball, tugging it straight, then letting it go, watching it shrink back into dark brown cotton candy.

“What colors you want?” I asked, separating the hair into the three parts.

“Ummmm…” Maddy put a finger to her chin, acting like she thinking. I say acting, because she knew what color she wanted. She picked the same one every week. Matter fact, there was only one color in the can.

“Red,” we both said at the same time, me, of course, with a little more pepper and a little less pep. Maddy tried to whip around and give me a funny face, but I was mid-braid.

“Uh-uh. Stay still.”

Then came the beading. Today, thirty braids. So, three red beads on each braid. Ninety beads. I used tiny bits of aluminum foil on the ends to keep the beads from slipping off, even though I knew they would anyway. But who got time to use those little rubber bands? Not me. And definitely not Maddy.

When we finished, Maddy did what she always did—ran to the bathroom. I followed her, like I always did, and lifted her up so she could see herself in the mirror. She smiled, her mouth like a piano with only one black key, one front tooth missing. Then Maddy ran back to the living room and blew a kiss at a picture propped up on the table next to the TV—the same picture every time—of me at her age, six, with a big cheese and a missing front tooth and braids, red beads, aluminum foil on the ends.

I do Maddy’s hair every Sunday for two reasons. The first is because Momly can’t do it. If it was up to her, Maddy’s hair would be in two Afro-puffs every day. Either that, or Momly would’ve shaved it all off by now. It’s not that she don’t care. She does. It’s just that she don’t know what to do with hair like Maddy’s—like ours. Ma do, but Momly… nope. She never had to deal with nothing like it, and there ain’t no rule book for white people to know how to work with black hair. And her husband, my uncle Tony, he ain’t no help. Ever since they adopted us, every time I talk about Maddy’s hair, Uncle Tony says the same thing—just let it rock. Like he’s gonna sit in the back of Maddy’s class and stink-face all the six-year-old bullies in barrettes. Right. But luckily for everybody, especially Maddy, I know what I’m doing. Been a black girl all my life.

The other reason I always do Maddy’s hair on Sundays is because that’s when we see Ma, and she don’t wanna see Maddy looking like “she ain’t never been nowhere.” So after Maddy’s hair is done, we get dressed. As in, dressed up. All the way up. Maddy puts on one of her church dresses, white patent leather shoes that most people only wear on Easter Sunday, but for us—for Ma—every Sunday is like Easter Sunday. I put on a dress too, run a comb through my hair until it cooperates. Ugly black ballerina flats because Ma don’t want me “looking fast in the house of the Lord.” Then Momly drives us across town to Barnaby Terrace, my old neighborhood.

Barnaby Terrace is… fine. I don’t really know what else to say about it except for the fact that there’s nothing really to say about it. Ain’t nobody rich, that’s for sure. But ain’t nobody really poor, neither. Everybody’s just regular. Regular people going to regular jobs having regular kids who go to regular schools and grow up to be regular people with regular jobs, and on and on. And I guess everything was pretty regular about me, too, until six years ago. Follow me. I’d just turned six, and me and my dad were having one of our famous invisible cupcake parties. Kinda like how little girls on old TV shows be having tea parties, but you know how it don’t ever really be tea in the cups? Like that. Except I didn’t have a tea set, and my mom wouldn’t let us use her real teacups, which were really just random coffee mugs, plus my dad always said tea don’t even taste good enough to pretend to drink it. He also said “tea” and “eat” are made of the same letters anyway, so pretending to eat was pretty much the same as pretending to drink. And what better thing to pretend to eat than cupcakes. And that’s what we always had—imaginary cupcakes.

But on this night, my mother cut the party short because it was a school night, plus she was pregnant with Maddy at the time and needed my father to massage her feet. So he whispered in my ear, “Sleep tight, sweet Pancake, your mama and the Waffle need me.” Then he kissed me good night—first on the forehead, then on one cheek, then on the other cheek. I don’t know what happened next. My guess is that after rubbing Ma’s feet, he kissed her good night too. And Maddy, the “Waffle” who was probably being all fidgety in Ma’s stomach. I bet Dad smooched right on the belly button, then rolled over and went to sleep.

But he never woke up.

Like… ever.

It was crazy. And if we had been allowed to drink pretend tea from my mother’s real cups, they all would’ve been shattered the next morning after she woke me up, her face wet with tears, and blurted, “Something’s happened.” I would’ve smashed each and every one of them cups on the floor. And I would’ve smashed more of them two years later when my mother had two toes cut off her right foot. And six months after that, when she had that whole foot cut off. And six months after that—three years ago—when my mother had both her legs chopped off, which, I’m telling you, would’ve left the whole stupid cabinet empty. Broken mugs everywhere. Nothing left to drink from.

But I didn’t. Instead I just swallowed it all. And wished this was all some kind of invisible, pretend… something. But it wasn’t.

And just so you don’t get the wrong idea, it’s not like my mom just wanted her legs cut off. She got the sugar. Well, it’s really a disease called diabetes, but she calls it the sugar, so I call it the sugar, plus I like that better than diabetes because diabetes got the word “die” in it, and I hate that word. The sugar broke Ma’s lower extremities, which is how doctors say legs. It just went crazy all in her body. Stopped the blood flow to her feet. I used to have to rub and grease them at night, just like my dad used to, and it was like putting lotion on two tree trunks. Dry and cracked. Swollen and dark like she’d been standing in coal. But at some point she just couldn’t feel them no more, and I went from moisturizing them to trying to rub them back to life. And after that, they were basically… I guess the best way to explain it is to just say… dead. Her feet had died. Like I said, I hate that word, but ain’t no way else to say it. And I guess death can travel, can spread like a fire in the body, so the doctors had to go ahead and cut her legs off—they call it “amputate,” which for some reason makes me think of something growing, not something being chopped—just above the knee to keep more of her from dying.

Maddy’s only six now, and ever since she was born I’d been helping out the best I could with her. But with Ma losing her toes and feet, helping out became straight-up taking care of. I’m talking about keeping lists in my head of things I had to take care of.

TO DO: Make sure Maddy’s bathed.

TO DO: Make sure Maddy’s dressed.

TO DO: Make sure Maddy’s fed.

TO DO: Everything.

But after Ma lost her legs, my godparents—my dad’s brother, Tony, and his wife, Emily—stepped in and took over as our “sole guardians,” which, the first time I heard it, I thought was “soul guardians,” which, I guess, is just as good. Kinda like guardian angels. I bet Uncle Tony and Auntie Emily—who Maddy used to call Mama Emily, which became Momly—had no idea that when they said they would be our godparents they were inheriting all this drama. I bet they just thought they’d have to give us gifts on random days—days that wasn’t our birthday or Christmas. Slip us ten-dollar bills just because. Stuff like that. Not take care of us, all the way. That’s… a lot. But they always acted like they were cool with it—like this is what they signed up for—and we grateful, even though I still gotta look out for Maddy because, you know… I just do. I still keep a list in my brain. Plus, Momly can’t do black hair for nothing.

Why am I telling you this long story?

Oh, I remember.

Because, Sundays. On Sundays, like I said, Maddy’s hair gotta be right. For Ma.

TO DO: Everything (including forgetting about the race and braiding my sister’s hair)

AIN’T NO SUCH thing as a false start. Because false means fake, and ain’t no fake starts in track. Either you start or you don’t. Either you run or you don’t. No in-between. Now, there can be a wrong start. That makes more sense to me. Means you just start at the wrong time. Just jump early and break out running with no one there running with you. No competition except for your own brain that swears there’s other people on your heels. But ain’t nobody there. Not for real. Ain’t no chaser. That’s what they really mean when they say false start. A real start at the wrong time. And at the first meet of the season, nobody knew this more than Ghost.

Before the race, me and everybody else stood on the sidelines, clapping and hyping Ghost and Lu up as they took their marks. This was of course after they had already gassed each other up, talking to each other like there was no one else on the track but them. Funny how they went from mean-muggin’ each other when they first met, to becoming all buddy-buddy like they their own two-man gang or something. Lu and Ghost—sticking together like glue. Ha! Glue! Ghost and Lu, Glue. Get it? That could be their corny crew name. Lost would also work. Matter fact, there was a moment where I thought that name might even be more fitting. Especially after what Ghost did.

See, at first, I thought he’d timed it perfectly. I thought Ghost pushed off from the line at the exact moment the gun went off, as if he just knew when it was coming. Like he could feel it on the inside of him or something. But he didn’t hear the second shot. Well, I take that back. Of course he heard it. It was a loud boom. It was impossible not to hear it. But he didn’t know it meant that he’d jumped too early, that he’d false started. I mean, this was his first race, so he had no clue that that second shot meant to stop running, and start over. So… he didn’t.

He ran the entire hundred meters. Didn’t know that people weren’t cheering him on, but were yelling for him to pull up, to go back to the starting line. So when he got to the finish line, he threw his hands up in victory and turned around with one of them million-toothed smiles until he noticed all the other runners—his competition—were still up at the top of the track. He looked out into the crowd. Everybody, laughing. Pointing. Shaking their heads, while Ghost dropped his. Stared at the black tar, his chest like someone blowing up a balloon inside him, then letting the air out, then blowing it back up, then letting the air out. I was afraid that balloon was gonna bust. That Ghost would burst open like he used to do when he first joined the team. And I could tell by the way he was chewing on the side of his jaw that he wanted to, or maybe just keep running, off the track, out of the park, all the way home.

Coach walked over to him, whispered something in his ear. I don’t know what it was. But it was probably something like, “It’s okay, it’s okay, settle down, you’re still in it. But if you do it again, you’re disqualified.” Nah, knowing Coach, it was probably something a little more deep, like… I don’t know. I can’t even think of nothing right now, but Coach was full of deep. Whatever it was, Ghost lifted his head and trotted back to the line, where Lu was waiting with his hand out for a five. Ghost was still out of breath, but there was no time for him to catch it. He had to get back down on his mark. Get ready to run it all over.

The starter held the gun in the air again. My stomach flipped over again. The man pulled the trigger again. Boom! again. And Ghost took off. Again. It was almost like his legs were sticks of dynamite, and the first run was just the fuse being lit, and now, the tiny fire had gotten to the blowup part. And let me tell you, Ghost… blew up. Busted wide open in the best way. I mean, the dude exploded down the line in a blur, even faster this time, his silver shoes like sparks flicking up off the track.

First race. First place.

Even after a false start.

And if a false start means a real start at the wrong time—the wrong time being too early—then I must’ve had a false finish, which also ain’t a fake finish, but a real finish, just… too late. Make sense?

Just in case it don’t, let me explain.

My race was up next. And here’s the thing, I’ve been running the eight hundred for three years straight. It’s my race. I have a system, a way of running it. I come off the block strong and low and by the time I’m straight up, my stride is steady, but I always allow myself to drop back a little. You know, keeping it cool for the first lap. Pace. That’s where eight-hundred runners blow it. They start out too fast and be rigged by the second lap. I seen a lot of girls get roasted out there, showboatin’ on that first four hundred. But I knew better. I knew the second four hundred was the kicker. What I didn’t know, though, was just how fast the girls in this new league were. What kinda shape they were in. So when the gun blew, and we took off, I realized that the pace I had to keep just to stay with the pack was faster than I was used to. But, of course, I’m thinking, these girls are stupid and are gonna be tired in twenty seconds.

In thirty seconds.

In forty seconds.

Never happened, and instead it ended up being me saying to myself, Oh God, I’m tired. How am I tired? And as we rounded into the final two hundred meters, I had to dig deep and step it up. So I turned on the jets.

Here’s how it went.

Cornrows, Low-Cut, Ponytail, and Puny-Tail in front of me. Chop ’em down, Patty. Push, push, push, breathe. Cornrows is on my side now. The crowd is screaming the traditional chant when someone is getting passed—Woooop! Woooop! Woooop! Push. Push. Cornrows is toast. One hundred meters to go. Mouth wide open. Eyes wide open. Stride wide open. Chop ’em down, Patty. Arms pumping, whipping the air out of my way like water. Low-Cut is slowing up. Her little pea-head’s bobbling like it could snap right off. She’s tired. Finally. Woooop! Woooop! Got her. Two more to go. Ponytail can feel me coming. She can probably hear my footsteps over the screaming crowd. She knows I’m close, and then she makes the biggest mistake ever—the one thing every coach tells you to never do—she looked back. See, when you look back, it automatically knocks your stride off and it gets you messed up mentally. And once Ponytail looked over her shoulder, the woooops started back up like a siren. Woooop! Woooop! Woooop! Fifty meters. That’s right, I’m coming. Chop ’em down, Patty. I’m coming. I could see Puny-Tail just ahead of her, that little twist of hair in the back of her head like a snake tongue. She was running out of breath. I could see that by the way her form had broken down. Ponytail was too. We all were. And even worse for me, we were also running out of track.

I got Ponytail by a nose—second place—then collapsed, people cheering all around me, jumping up and down in the stands quickly becoming a wavy blur of color as the tears rose. Second? Stupid second place? Ugh. No way was I going to cry. Trust me, I wanted to, water pricking at my eyelids, but no way. I wanted to kick something, I was so mad! Coach Whit came over and helped me up, and once I was standing, I yanked away from her and limped over to the bench. My legs were burning and cramping, but I wanted to kick something anyway. Maybe kick the bench over. Kick those stupid orange slices Lu’s mother brought. Anything. But instead I just sat down and didn’t say a word for the rest of the meet. Yes, I’m a sore loser, if that’s what you wanna call it. To me, I just like to win. I only wanna win. Anything else is… false. Fake.

But real.

So real, I didn’t even want to talk about it on the way to church the next day. Not with no one. Not even with God. I’d spent all morning braiding Maddy’s hair the same way Ma used to braid mine when I was little. Only difference is Ma got fat fingers, and used to be braiding like she was trying to strip my edges or make me bald. Talkin’ ’bout, “Gotta make it tight so it don’t come loose.” Right. But I don’t even do Maddy’s that tight, and I can knock out a whole head full of hair in half an hour if she sits still. Which she never does.

“How many more?” Maddy whined, squirming on the floor in front of me.

“I’m almost done. Just chill out, so I can…” I picked up the can of beads and shook them in her ear like one of them Spanish shaker things. And just like that, she calmed down and let me tilt her head forward so I could braid the last section, the bit of curls tightly wound at the base of her neck. I dipped my finger in the gunk on the back of my hand, then massaged it into Maddy’s scalp. Then I stroked grease into the leftover bush-ball, tugging it straight, then letting it go, watching it shrink back into dark brown cotton candy.

“What colors you want?” I asked, separating the hair into the three parts.

“Ummmm…” Maddy put a finger to her chin, acting like she thinking. I say acting, because she knew what color she wanted. She picked the same one every week. Matter fact, there was only one color in the can.

“Red,” we both said at the same time, me, of course, with a little more pepper and a little less pep. Maddy tried to whip around and give me a funny face, but I was mid-braid.

“Uh-uh. Stay still.”

Then came the beading. Today, thirty braids. So, three red beads on each braid. Ninety beads. I used tiny bits of aluminum foil on the ends to keep the beads from slipping off, even though I knew they would anyway. But who got time to use those little rubber bands? Not me. And definitely not Maddy.

When we finished, Maddy did what she always did—ran to the bathroom. I followed her, like I always did, and lifted her up so she could see herself in the mirror. She smiled, her mouth like a piano with only one black key, one front tooth missing. Then Maddy ran back to the living room and blew a kiss at a picture propped up on the table next to the TV—the same picture every time—of me at her age, six, with a big cheese and a missing front tooth and braids, red beads, aluminum foil on the ends.

I do Maddy’s hair every Sunday for two reasons. The first is because Momly can’t do it. If it was up to her, Maddy’s hair would be in two Afro-puffs every day. Either that, or Momly would’ve shaved it all off by now. It’s not that she don’t care. She does. It’s just that she don’t know what to do with hair like Maddy’s—like ours. Ma do, but Momly… nope. She never had to deal with nothing like it, and there ain’t no rule book for white people to know how to work with black hair. And her husband, my uncle Tony, he ain’t no help. Ever since they adopted us, every time I talk about Maddy’s hair, Uncle Tony says the same thing—just let it rock. Like he’s gonna sit in the back of Maddy’s class and stink-face all the six-year-old bullies in barrettes. Right. But luckily for everybody, especially Maddy, I know what I’m doing. Been a black girl all my life.

The other reason I always do Maddy’s hair on Sundays is because that’s when we see Ma, and she don’t wanna see Maddy looking like “she ain’t never been nowhere.” So after Maddy’s hair is done, we get dressed. As in, dressed up. All the way up. Maddy puts on one of her church dresses, white patent leather shoes that most people only wear on Easter Sunday, but for us—for Ma—every Sunday is like Easter Sunday. I put on a dress too, run a comb through my hair until it cooperates. Ugly black ballerina flats because Ma don’t want me “looking fast in the house of the Lord.” Then Momly drives us across town to Barnaby Terrace, my old neighborhood.

Barnaby Terrace is… fine. I don’t really know what else to say about it except for the fact that there’s nothing really to say about it. Ain’t nobody rich, that’s for sure. But ain’t nobody really poor, neither. Everybody’s just regular. Regular people going to regular jobs having regular kids who go to regular schools and grow up to be regular people with regular jobs, and on and on. And I guess everything was pretty regular about me, too, until six years ago. Follow me. I’d just turned six, and me and my dad were having one of our famous invisible cupcake parties. Kinda like how little girls on old TV shows be having tea parties, but you know how it don’t ever really be tea in the cups? Like that. Except I didn’t have a tea set, and my mom wouldn’t let us use her real teacups, which were really just random coffee mugs, plus my dad always said tea don’t even taste good enough to pretend to drink it. He also said “tea” and “eat” are made of the same letters anyway, so pretending to eat was pretty much the same as pretending to drink. And what better thing to pretend to eat than cupcakes. And that’s what we always had—imaginary cupcakes.

But on this night, my mother cut the party short because it was a school night, plus she was pregnant with Maddy at the time and needed my father to massage her feet. So he whispered in my ear, “Sleep tight, sweet Pancake, your mama and the Waffle need me.” Then he kissed me good night—first on the forehead, then on one cheek, then on the other cheek. I don’t know what happened next. My guess is that after rubbing Ma’s feet, he kissed her good night too. And Maddy, the “Waffle” who was probably being all fidgety in Ma’s stomach. I bet Dad smooched right on the belly button, then rolled over and went to sleep.

But he never woke up.

Like… ever.

It was crazy. And if we had been allowed to drink pretend tea from my mother’s real cups, they all would’ve been shattered the next morning after she woke me up, her face wet with tears, and blurted, “Something’s happened.” I would’ve smashed each and every one of them cups on the floor. And I would’ve smashed more of them two years later when my mother had two toes cut off her right foot. And six months after that, when she had that whole foot cut off. And six months after that—three years ago—when my mother had both her legs chopped off, which, I’m telling you, would’ve left the whole stupid cabinet empty. Broken mugs everywhere. Nothing left to drink from.

But I didn’t. Instead I just swallowed it all. And wished this was all some kind of invisible, pretend… something. But it wasn’t.

And just so you don’t get the wrong idea, it’s not like my mom just wanted her legs cut off. She got the sugar. Well, it’s really a disease called diabetes, but she calls it the sugar, so I call it the sugar, plus I like that better than diabetes because diabetes got the word “die” in it, and I hate that word. The sugar broke Ma’s lower extremities, which is how doctors say legs. It just went crazy all in her body. Stopped the blood flow to her feet. I used to have to rub and grease them at night, just like my dad used to, and it was like putting lotion on two tree trunks. Dry and cracked. Swollen and dark like she’d been standing in coal. But at some point she just couldn’t feel them no more, and I went from moisturizing them to trying to rub them back to life. And after that, they were basically… I guess the best way to explain it is to just say… dead. Her feet had died. Like I said, I hate that word, but ain’t no way else to say it. And I guess death can travel, can spread like a fire in the body, so the doctors had to go ahead and cut her legs off—they call it “amputate,” which for some reason makes me think of something growing, not something being chopped—just above the knee to keep more of her from dying.

Maddy’s only six now, and ever since she was born I’d been helping out the best I could with her. But with Ma losing her toes and feet, helping out became straight-up taking care of. I’m talking about keeping lists in my head of things I had to take care of.

TO DO: Make sure Maddy’s bathed.

TO DO: Make sure Maddy’s dressed.

TO DO: Make sure Maddy’s fed.

TO DO: Everything.

But after Ma lost her legs, my godparents—my dad’s brother, Tony, and his wife, Emily—stepped in and took over as our “sole guardians,” which, the first time I heard it, I thought was “soul guardians,” which, I guess, is just as good. Kinda like guardian angels. I bet Uncle Tony and Auntie Emily—who Maddy used to call Mama Emily, which became Momly—had no idea that when they said they would be our godparents they were inheriting all this drama. I bet they just thought they’d have to give us gifts on random days—days that wasn’t our birthday or Christmas. Slip us ten-dollar bills just because. Stuff like that. Not take care of us, all the way. That’s… a lot. But they always acted like they were cool with it—like this is what they signed up for—and we grateful, even though I still gotta look out for Maddy because, you know… I just do. I still keep a list in my brain. Plus, Momly can’t do black hair for nothing.

Why am I telling you this long story?

Oh, I remember.

Because, Sundays. On Sundays, like I said, Maddy’s hair gotta be right. For Ma.

Reading Group Guide

A Reading Group Guide to

Patina

By Jason Reynolds

About the Book

Patina “Patty” Jones may be a newbie on the Defenders track team, but she is determined to be the best. Her mother always tells her that “she ain’t no junk.” Still, Patty’s been through her share of problems, from her father’s sudden death to her mother’s battle with diabetes. When complications from the disease cause her mother to lose her legs, Patty and her little sister Maddy move in with Uncle Tony and Aunt Emily. Now Patty is living in a different house, attending a fancy new school filled with rich kids, and trying to be a good example for Maddy. Patty has gotten used to taking care of things herself and not depending on anyone else, but after Coach puts her on a relay and her teacher assigns a group project with the snobbiest hair flippers of all, she learns that the only way to win is to come together as a team.

Discussion Questions

1. Do you think Patty was right to be upset about coming in second in her first race with the Defenders? What does her response to the second-place finish reveal about her personality?

2. Why do Maddy and Patina need to live with Momly and Uncle Tony? How is life different than it was in her old house in Barnaby Terrace?

3. Why did Patty start running track? Toward the end of the book, she says that running helps her by giving her a way to “Leave everything, all the hurting stuff. . .in the dust.” What activity helps you feel better when you are stressed or anxious?

4. Describe the relationship between Maddy and Patina. How does Maddy feel about her big sister? How can you tell? How does Patty feel about her little sister? Find a detail in the book that reveals something about the sisters’ relationship.

5. Why did Patty change schools? How is her new school different from Barnaby Middle? What does she miss most about her old school? How would you describe your school? What do you like the best about it? What would you like to change?

6. How can you tell that Patty’s mother loves and emotionally supports her even though she can’t physically take care of her? How have the adults in your life shown you that they support you?

7. When they are assigned the history project on an important woman from the past, each member of Patty’s group wants to choose a different person. Who does Patty suggest? Who does Becca suggest? If you were given this project, who would you want to research?

8. Why does Patty dislike group projects? Do you agree with her reasons? Why is it important to learn to work with a group? What does Patty learn about her classmates after working with them on the project?

9. When Patty is placed in a relay, she spends time learning how to be part of a team. How do her coaches teach the girls to work together? What do you think it means to be a good teammate?

10. Why is lunchtime challenging for Patty? Do you enjoy lunchtime and free time, or do you dread them? What could you do to make sure that nobody feels left out or lonely at your school?

11. When Patty moves in with Momly and Uncle Tony and changes schools, she is not as close to her best friend, Cotton. What specific things does she miss about spending time with Cotton? Who is your best friend? What do you enjoy doing with them?

12. What causes the fight between Krystal and Patty? What mistakes did each girl make? What strategies helped them resolve their disagreement?

13. In chapter 5, Patty, Lu, and Ghost laugh and tease one another after Coach makes them ballroom dance on the track. Why do the three friends accept this kind of behavior from one another? What might the reaction have been if Patty had said the same thing to kids who were not her close friends? Can you think of other instances in your life when you’ve said something to a friend that could have been interpreted differently if you’d said it to someone else? Why do you think friends are able to tease each other in a way that’s funny, rather than hurtful?

14. Why do you think it is hard for Patty to tell people about her mom’s illness and her father’s death? What happens when she does talk about it? Have you ever held your feelings in? What happened?

15. What does Patty learn about Momly’s childhood? How does this knowledge change her perception of Momly? How does it change her perception of her school?

16. Why is Patty surprised when she visits Becca’s house? Why do you think Becca hides her love of space from her classmates at school? Do you think she’s pretending to be someone she isn’t when she is at school?

17. Sometimes we don’t really appreciate things until they are gone. What event helps Patty appreciate Momly? How does she show her appreciation?

18. Compare the race at the end of the novel to the race at the beginning. How has Patty grown and changed?

19. Jason Reynolds chooses to end the novel without letting the reader know the results of the race. Why do you think he ends his novel this way?

20. So far, each of the novels in this series has focused on a different member of the Defenders: Ghost and Patina. Who would you like to see featured in the next novel? What do you want to know about them?

Extension Activities

1. Patina’s mother lives with diabetes. Do you know anyone with diabetes? Visit the American Diabetes Association website (http://www.diabetes.org/) to learn more about this disease. Consider joining Team Diabetes and plan or participate in a community athletic event to raise awareness and/or funds to help find a cure for diabetes.

2. Patty and her classmates choose to research the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo for their school project. Research the life and art of Frida Kahlo and use what you have learned to create your own project. If you enjoy art, you may want to include a self-portrait in the style of the artist.

3. Coach has the girls on the relay team practice waltzing to learn to work together. Research teambuilding activities online and vote on one to play as a class or group. Do you feel differently after working together on the activity?

4. Read the poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by Tennyson (the poem can be found online at www.poetryfoundation.org) and research the battle that inspired the poem. Why do you think Patty ends up connecting to this poem? We usually think of poems as being personal and expressing emotions, but lyric poetry is only one form of poetry. Using Tennyson’s poem as a model, try writing your own narrative or dramatic poem about a real-life event.

5. Patina is written using first person narration, which means that the story is told from Patty’s point of view. To write this way, Jason Reynolds had to develop a unique voice for Patty. Compare Patty’s voice in this novel to other first person narrators (in particular, the narrator of Ghost, the first book in this series). Try writing in the style of one of your favorite first person narrators.

6. One of Patty’s heroes is Florence Griffith Joyner (Flo Jo). Research her life and accomplishments. Why do you think Patina admires her?

Guide prepared by Amy Jurskis, English Department Chair at Oxbridge Academy in Florida.

This guide has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

Patina

By Jason Reynolds

About the Book

Patina “Patty” Jones may be a newbie on the Defenders track team, but she is determined to be the best. Her mother always tells her that “she ain’t no junk.” Still, Patty’s been through her share of problems, from her father’s sudden death to her mother’s battle with diabetes. When complications from the disease cause her mother to lose her legs, Patty and her little sister Maddy move in with Uncle Tony and Aunt Emily. Now Patty is living in a different house, attending a fancy new school filled with rich kids, and trying to be a good example for Maddy. Patty has gotten used to taking care of things herself and not depending on anyone else, but after Coach puts her on a relay and her teacher assigns a group project with the snobbiest hair flippers of all, she learns that the only way to win is to come together as a team.

Discussion Questions

1. Do you think Patty was right to be upset about coming in second in her first race with the Defenders? What does her response to the second-place finish reveal about her personality?

2. Why do Maddy and Patina need to live with Momly and Uncle Tony? How is life different than it was in her old house in Barnaby Terrace?

3. Why did Patty start running track? Toward the end of the book, she says that running helps her by giving her a way to “Leave everything, all the hurting stuff. . .in the dust.” What activity helps you feel better when you are stressed or anxious?

4. Describe the relationship between Maddy and Patina. How does Maddy feel about her big sister? How can you tell? How does Patty feel about her little sister? Find a detail in the book that reveals something about the sisters’ relationship.

5. Why did Patty change schools? How is her new school different from Barnaby Middle? What does she miss most about her old school? How would you describe your school? What do you like the best about it? What would you like to change?

6. How can you tell that Patty’s mother loves and emotionally supports her even though she can’t physically take care of her? How have the adults in your life shown you that they support you?

7. When they are assigned the history project on an important woman from the past, each member of Patty’s group wants to choose a different person. Who does Patty suggest? Who does Becca suggest? If you were given this project, who would you want to research?

8. Why does Patty dislike group projects? Do you agree with her reasons? Why is it important to learn to work with a group? What does Patty learn about her classmates after working with them on the project?

9. When Patty is placed in a relay, she spends time learning how to be part of a team. How do her coaches teach the girls to work together? What do you think it means to be a good teammate?

10. Why is lunchtime challenging for Patty? Do you enjoy lunchtime and free time, or do you dread them? What could you do to make sure that nobody feels left out or lonely at your school?

11. When Patty moves in with Momly and Uncle Tony and changes schools, she is not as close to her best friend, Cotton. What specific things does she miss about spending time with Cotton? Who is your best friend? What do you enjoy doing with them?

12. What causes the fight between Krystal and Patty? What mistakes did each girl make? What strategies helped them resolve their disagreement?

13. In chapter 5, Patty, Lu, and Ghost laugh and tease one another after Coach makes them ballroom dance on the track. Why do the three friends accept this kind of behavior from one another? What might the reaction have been if Patty had said the same thing to kids who were not her close friends? Can you think of other instances in your life when you’ve said something to a friend that could have been interpreted differently if you’d said it to someone else? Why do you think friends are able to tease each other in a way that’s funny, rather than hurtful?

14. Why do you think it is hard for Patty to tell people about her mom’s illness and her father’s death? What happens when she does talk about it? Have you ever held your feelings in? What happened?

15. What does Patty learn about Momly’s childhood? How does this knowledge change her perception of Momly? How does it change her perception of her school?

16. Why is Patty surprised when she visits Becca’s house? Why do you think Becca hides her love of space from her classmates at school? Do you think she’s pretending to be someone she isn’t when she is at school?

17. Sometimes we don’t really appreciate things until they are gone. What event helps Patty appreciate Momly? How does she show her appreciation?

18. Compare the race at the end of the novel to the race at the beginning. How has Patty grown and changed?

19. Jason Reynolds chooses to end the novel without letting the reader know the results of the race. Why do you think he ends his novel this way?

20. So far, each of the novels in this series has focused on a different member of the Defenders: Ghost and Patina. Who would you like to see featured in the next novel? What do you want to know about them?

Extension Activities

1. Patina’s mother lives with diabetes. Do you know anyone with diabetes? Visit the American Diabetes Association website (http://www.diabetes.org/) to learn more about this disease. Consider joining Team Diabetes and plan or participate in a community athletic event to raise awareness and/or funds to help find a cure for diabetes.

2. Patty and her classmates choose to research the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo for their school project. Research the life and art of Frida Kahlo and use what you have learned to create your own project. If you enjoy art, you may want to include a self-portrait in the style of the artist.

3. Coach has the girls on the relay team practice waltzing to learn to work together. Research teambuilding activities online and vote on one to play as a class or group. Do you feel differently after working together on the activity?

4. Read the poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by Tennyson (the poem can be found online at www.poetryfoundation.org) and research the battle that inspired the poem. Why do you think Patty ends up connecting to this poem? We usually think of poems as being personal and expressing emotions, but lyric poetry is only one form of poetry. Using Tennyson’s poem as a model, try writing your own narrative or dramatic poem about a real-life event.

5. Patina is written using first person narration, which means that the story is told from Patty’s point of view. To write this way, Jason Reynolds had to develop a unique voice for Patty. Compare Patty’s voice in this novel to other first person narrators (in particular, the narrator of Ghost, the first book in this series). Try writing in the style of one of your favorite first person narrators.

6. One of Patty’s heroes is Florence Griffith Joyner (Flo Jo). Research her life and accomplishments. Why do you think Patina admires her?

Guide prepared by Amy Jurskis, English Department Chair at Oxbridge Academy in Florida.

This guide has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books (October 23, 2018)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481450195

- Ages: 10 - 99

- Lexile ® 710L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Awards and Honors

- ALA Notable Children's Books

- ILA Teachers' Choices

- CCBC Choices (Cooperative Children's Book Council)

- Chicago Public Library's Best of the Best

- Dorothy Canfield Fisher Book Award Master List (VT)

- ALA Top Ten Quick Picks for Reluctant Young Adult Readers

- Bank Street Best Children's Book of the Year Selection Title

- ALA Notable Children's Recording

- Amazing Audiobooks for YA

- Wisconsin State Reading Association's Reading List

- Lectio Book Award Finalist (TX)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Patina Trade Paperback 9781481450195

- Author Photo (jpg): Jason Reynolds Photograph (c) Adedayo "Dayo" Kosoko(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit