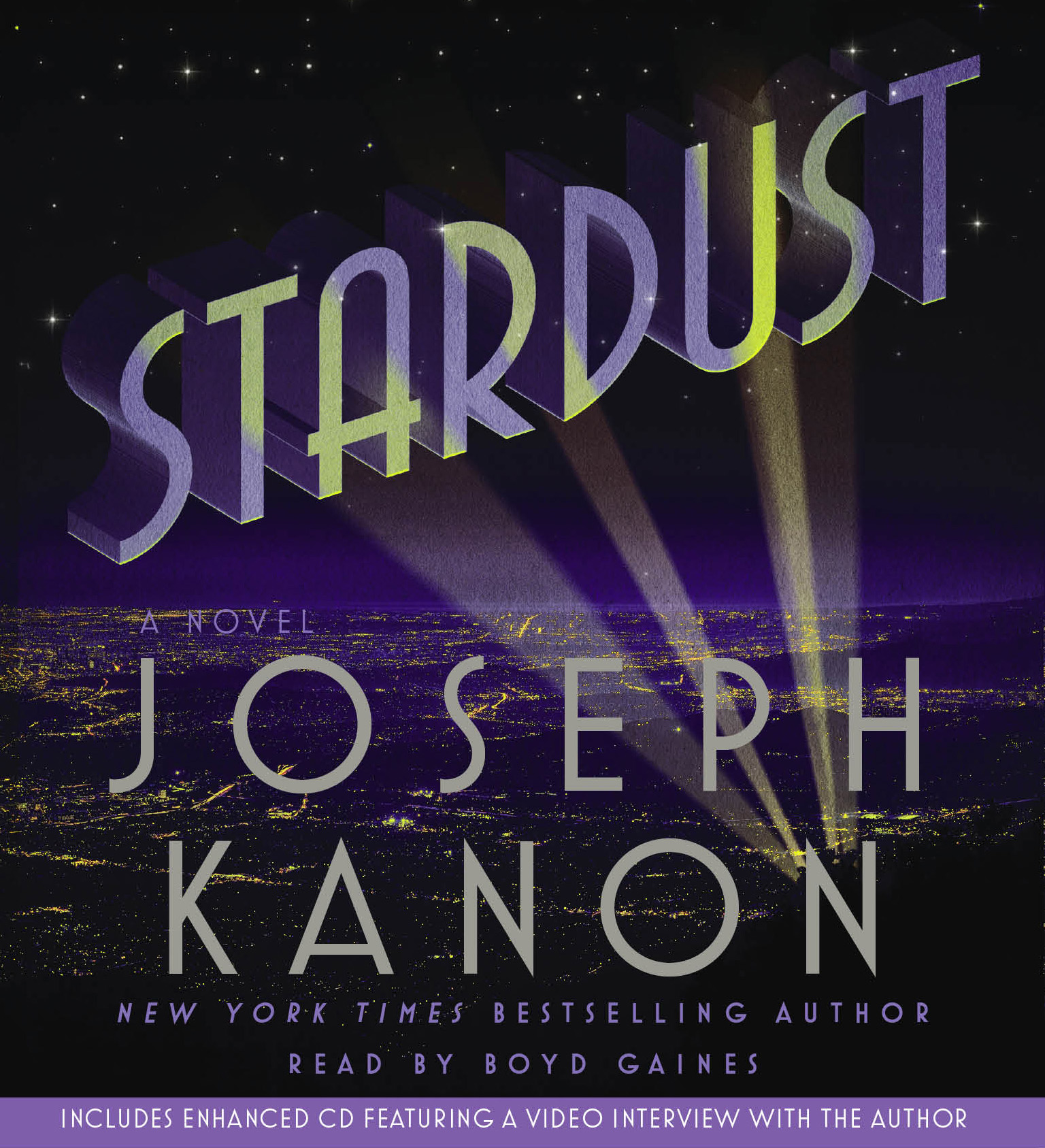

Stardust

A Novel

LIST PRICE $19.99

Digital products purchased on SimonandSchuster.com must be read on the Simon & Schuster Books app. Learn more.

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Hollywood, 1945. Ben Collier has just arrived from war-torn Europe to find his brother has died in mysterious circumstances. Why would a man with a beautiful wife, a successful movie career, and a heroic past choose to kill himself?

Ben enters the uneasy world beneath the glossy shine of the movie business, where politics and the dream factories collide and Communist witch hunts are rendering the biggest star makers vulnerable. Even here, where the devastation of Europe seems no more real than a painted movie set, the war casts long and dangerous shadows. When Ben learns troubling facts about his own family’s past and embarks on a love affair that never should have happened, he is caught in a web of deception that shakes his moral foundation to its core.

Rich with atmosphere and period detail, Stardust flawlessly blends fact and fiction into a haunting thriller evoking both the glory days of the movies and the emergence of a dark strain of American political life.

Reading Group Guide

Introduction

In post-WWII Hollywood, Ben Collier has returned from the front lines to find that his brother Danny has died from a fall off a hotel balcony. But the information surrounding Danny’s accident is blurred, and Ben makes his way to Los Angeles wondering why Danny, a war hero and burgeoning filmmaker, would leave behind a life of promise and respect. Or was it not his choice after all?

Joseph Kanon’s most intricate novel to date, Stardust follows Ben on an informative and mysterious trek through the hush-hush world of 1940s Hollywood. As he attempts to piece together the specifics of his brother’s death, Ben is hurled into a stream of secret deals, political maneuvering, and the beginning murmurs of the Hollywood Communist witch hunts.

With a lush depiction of the era, Kanon weaves a tale of intrigue, suspense, and romance that looks behind the film lens and into the hearts of émigrés and American moviemakers of the time. Lights, camera, action…

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. Did you expect the final outcome? Did the identity of Danny’s murderer come as a shock?

2. Discuss Liesl and her numerous lovers over the course of the narrative. (Consider Danny, Ben, and Dick Marshall). Did she ever love Ben, or was he just an extension of Danny? As Ben asks, “Was any of it real?”

3. Discuss the courtroom debate between Minot and Lasner. Who do you think won in the end? Did Lasner successfully thwart Minot’s attack on Hollywood, or did he merely delay the inevitable?

4. Ben is supplied information (and misinformation) by a variety of questionable sources. Did you trust his various informants? (Consider Kelly, Riordan, Polly, Minot, and Bunny Jenkins).

5. Bunny is one of the more complex characters within the narrative, a child star turned Hollywood Studio second-in-command and “fixer.” Discuss his evolution and multiplicity. How did you interpret his relationship with Jack (the mangled veteran)? Or his compliance with Minot’s proposed witch hunt? And, of course, consider his role in saving Ben’s life. Did you ever have a firm grasp on his character, or intentions?

6. Did you trust Ben’s deductive skills? He was led down the wrong path on numerous occasions. Were Liesl and Riordan right in persuading him to let Danny go? Is he any better off once Danny’s past allegiances are uncovered?

7. Murder plays a large role throughout the story, as two killings spur Danny to uncover the secrets behind the studio and the Red Scare. Were you certain as to why Danny had to die? What about Genia, the Holocaust survivor?

8. Where do you think Ben goes after watching War Bride?

9. Who was your favorite starlet in Stardust’s versions of Hollywood? Rosemary? Paulette Goddard? The new and improved Liesl Eastman? Are any of them safe from Minot and Polly Marks?

10. Who makes a better case for Ben’s future in Hollywood? Bunny, or Lasner?

Expand Your Book Club

1. Read another thriller/mystery novel, such as Le Carre’s A Most Wanted Man or a title from Ferrigno’s Assassin series, and discuss the way the writers build up and establish intrigue, and the methods by which they reveal the truth.

2. There is an immense amount of misinformation, secret connections, and crossed lines throughout the narrative. See if you can draw a map that clearly indicates how everyone is associated, who supplied whom with information, and how Dieter’s machinations work underneath it all.

3. The novel is a representation of a very specific era of Hollywood. Watch some of the movies from that era to get a better idea of what Tinsel Town was producing during the 1940s. Try You’ll Never Get Rich (Rita Hayworth, 1941) or Casablanca (Ingrid Bergman, 1942). There is also a rich selection of German cinema from this informative period, mentioned frequently in the beginning of the text. See any of Fritz Lang or Brecht’s seminal post-occupation films.

4. Continuing with the previous question, do you find any Communist or Socialist undertones in these films? Could you make a case for or against an imaginary Red inquisition?

5. Who would you cast in the Stardust movie?

A Conversation with Joseph Kanon

1. You obviously did a great amount of period-specific research for the book. What was the information-gathering process like for such an undertaking?

All of my books begin with a place. I have to know where my characters live, how the streets look to them. The best way to get a feel for a city is to walk it—for The Good German I spent days walking all over Berlin, trying to imagine the ruined city of 1945 beneath the modern one, a kind of literary archaeology. Los Angeles resists that kind of walking—you have to drive it—but the period details required a similar re-imagining. Many of the settings in Stardust still exist: the emigres’ houses (Feuchtwanger’s, Salka Viertel’s, etc.), the studios, Mt. Wilson, the Farmers Market, Union Station. But they exist in a very different city. In 1945 there were no freeways, streetcars ran down Hollywood Boulevard, there were still orange groves in the Valley. And it felt more remote. The fastest train from Chicago took 40 hours (and a full weekend from New York). Beverly Hills a generation before had been bean fields.

You can learn a great deal from old photographs and histories, but by far the most useful source of period details are memoirs. Luckily, Hollywood has provided an almost endless stream of anecdotes, memoirs and biographies, and while they’re often self-serving or misleading about their subjects, they’re usually accurate about the way people lived. This kind of research can be so enjoyable that the problem is having to stop.

The more serious area was the political climate—the union infighting, the red baiting and beginning of the witch hunts. The trick here is not only getting the background right, but getting the tone right. It’s impossible to quote directly from the actual transcripts of the hearings. The exchanges are so ludicrous and shameful that they seem implausible now. So in an odd way you have to elevate them, give them an intellectual seriousness they never had, and still somehow capture their almost surreal circus atmosphere.

2. Ben seems to possess an inexplicable detective’s intuition. What makes him such a good sleuth?

I don’t know that he’s a particularly good detective—he’s just following his nose and wherever logic seems to lead him. I’ve never written a book with a professional detective because I don’t have any idea how they actually work, what tricks they know. I just have Ben do what anyone would do. If you suspect something’s wrong, how do you go about finding the truth? Of course, playing detective is also simply a convention of the genre—if there’s a murder, somebody has to investigate or you don’t have a story. But I found it useful to have Ben get things wrong too. Stardust is about seeing, about the dust that gets in the way of our seeing things clearly, sometimes because we’d rather not see. And of course it’s complicated here by being set in a community whose business is illusion.

3. What are your favorite movies from Stardust-era Hollywood?

1939 is generally considered Hollywood’s annus mirabilis, the peak year of the studio era, but the golden period continued right through the 40s, when Stardust is set. Favorites? Too many to list, but I never tire of watching Preston Sturges’ The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story, to me the wittiest comedies ever filmed. Notorious is perfect entertainment, Double Indemnity still the best—and best written—film noir. Is there anyone who doesn’t love Casablanca? Meet Me in St. Louis is a beautifully made sentimental piece. Citizen Kane is inevitably on the top of every list.

It’s important to remember, though, that even during the golden years, first-rate movies like these were rare. We know the movies that endured, not necessarily the ones audiences liked then, and few things change faster than pop culture. The Crosby-Hope Road pictures, big hits at the time, are barely watchable now. The Bells of St. Mary’s was far and away the most successful movie of 1945. To us the big stars of the 40s are Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Rita Hayworth, Cary Grant and indeed they were big stars, but the box office champs were Bing Crosby and Betty Grable and her musicals aren’t even redeemed by camp now—they’re just inane.

4. Considering the subject matter of Stardust, it must have been useful to see The Good German translated to film. How do you feel about literature adapted for Hollywood?

I wasn’t involved in the making of The Good German, so the one really didn’t affect the other. I did, however, visit the set and that was useful because the director, Steven Soderbergh, wanted to made the movie that way it would have been done in 1945—shooting on sound stages and studio back lots, even using the same camera lenses that would have been available then. So in a sense I got to spend time on a set that might actually have been in Stardust. This even extended to the breaks between set-ups. Because The Good German was a period movie, all the actors were in 1945 dress—upswept hair, bright lipstick, uniforms, etc. To see the extras milling around the lot was to see exactly how it would have looked in 1945. The movie was shot on the old Columbia lot on Gower, just across the street from Continental in Stardust, so even the buildings had the right period feel.

The book-to-movie transition has always been difficult for writers—they are notorious complainers about film adaptations—because what they really want to see is an illustrated version of the novel that’s already in their heads. But film isn’t a visual translation, it’s a medium unto itself, made by other people. The best a writer can hope for is that talented people are taken by something in his material that prompts them to do good work of their own.

I don’t think there are any hard and fast rules about adaptations. It’s often just the luck of the draw. Lolita didn’t seem a natural for the screen but Kubrick made an interesting movie from it anyway. The 1940 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (script by Aldous Huxley) is still a delight, if not what Jane Austen intended. But does it really matter? The original books remain just as they were, still available, as rich and complex as ever. Why can’t we enjoy both?

The problem is that movies are so central to our popular culture that we tend of think as adaptations as replacements. They’re not. And the better the book, the less likely it is to be replaced. I suppose you could see Gone With the Wind without ever reading Margaret Mitchell and not miss much, but even though Garbo is in Anna Karenina and Gwyneth Paltrow made a fine Emma, imagine how much you’d miss by not reading the books. Of course, this process also works the other way—a movie can drive readers back to the book, always a good thing.

5. There has always been a large interest in following a child star’s coming of age. How do you view Bunny’s rise to the upper echelons of studio business? Or is it a fall from the limelight?

Bunny is one of the most complicated characters in the book and to me in some ways the most interesting. He represents the generation that will succeed the pioneering moguls and as such will steer the studio system through radical change (and eventual collapse) but he’s very much a product of that system—he grew up in it—so his feelings are contradictory. There is a built-in poignancy, a sense of loss, to the lives of child stars. Very few of them ever carry their careers into adulthood (Elizabeth Taylor being a notable exception). But there’s a built-in toughness too—they learn at an early age how arbitrary and unfair life can be.

Bunny has both these qualities. He prides himself on being pragmatic and shrewd, but he is still hopelessly romantic about movies. He knows that Hollywood will change—he is alert to the rise of television, he is willing to compromise people and principles for the sake of the studio—but he is not yet one of the corporate suits who would take over what was left of the studios in the 60s and 70s. He cares about making movies, not just making money. He can be manipulative, even Machiavellian, a cold-blooded plotter, and yet when he stands outside a closed set he’s looking at his own version of paradise lost, when he worked with people “closer than family”. Now he’s the boss. He’s clear-eyed about this—what’s past is past—but a part of him will always feel outside too.

6. This novel has a very cinematic feel. Did you think about a big screen version while writing it? Who would you cast in the Stardust movie?

To me writing is like making a movie in your head, the only one you can control, that’s really yours. What appears on the screen is inevitably someone else’s. So I don’t consciously think of movies as I write, what would work on the screen. But possibly what makes the books feel cinematic is that I tend to shape the narrative in scenes and rely heavily on dialogue. I like scenes where more than one thing is happening at once—in this case, say the dinner party at Sol Lasner’s house, when four or five plot elements are overlapping. The challenge for the writer, aside from the dialogue itself, which keeps the scene going, is knowing when and how to shift emphasis, moving the reader through it, in much the same way as a director has to know where to place the camera.

As for casting, this is everybody’s favorite parlor game. At bookstore readings I’m constantly asked whom I think should play a character or even whom I had in mind when I was writing. The truth is that the characters have to be so real to you that they can only be themselves, not look like anyone else. That having been said, there’s no denying the extraordinary power of film. I may not have thought of Jake and Lena as George Clooney and Cate Blanchett when I was writing The Good German, but that’s how they look to me now. As a matter of fact, I think they’d look right in Stardust too.

7. With all the duplicity and background connections in the book, did you have a hard time keeping track during the writing process? Was there a particular way in which you organized the book?

No, I never work from outlines or plans. Aside from having a general idea of what will happen—and certainly the whodunit—I tend to make things up as I go along. I like that surprise of seeing where the story will take you, the detours. In Stardust, though, I did reach a point where things became so complicated that I started keeping track of the scenes—what in the movies would be called continuity. This mostly had to do with chronology, when somebody would have known something, etc. And there were broader problems of chronology in the backstory—when did Danny and Ben last see each other, how old would Ben have been when his mother died, etc.

Strictly speaking none of these really affect the ongoing action, but I find that readers tend to trust the larger story more if you get the small details right. The Congressional hearings in Stardust take place earlier than the actual ones did, but the schedule for the Super Chief is accurate, right to the minute. And since I assumed, or hoped, that Stardust might appeal to film buffs all the industry details are true: Paulette Goddard was about to do a picture with Milland, Saratoga Trunk was released as described, the palms in the Cocoanut Grove really were from the set of The Sheik, or so sources said. This sort of thing may seem insignificant, but I think details give the story weight. And of course they’re fun to research.

8. What was the most challenging aspect of writing such an intricate narrative?

Trying to keep it to a manageable length. The material is so rich that I wanted to do more, particularly about Hollywood itself, but the book kept getting longer and you don’t want to try the reader’s patience. The front story—the crime and Ben’s solving it—inevitably takes up space at the expense of the backstory, which to me was a portrait of Hollywood just before it began to fall apart.

The seeds of that fall are there but some aren’t covered as extensively as I originally intended. The all-important Justice Department consent decree (separating the studios and their theaters), which would hit the studios with a financial body blow, is referred to here—it’s the reason Minot’s been invited to Lasner’s party—but not in great detail. The internal politics of the labor unions were too complicated (and, frankly, dated) to develop, so I had to be content with some conversation and a strike action. Television appears only in one scene but at least that’s consistent with how little attention the studios themselves gave it in 1945.

Other factors in the decline—the sense of the audience changing, the complacency hat set in with the wartime boom years—were more subtle and could be explored through the characters. Only the anti-Communist hearings became a centerpiece in the story, not only because they’re inherently dramatic but because they open a window on Hollywood’s vulnerabilities: its reliance on fickle public opinion, the special sensitivity of an industry run largely by assimilated Jews, revered for its patriotism during the war and now accused of being traitorous and un-American. The poison that these hearings introduced into the American body politic would go on for years and affect virtually every aspect of American life, but the poison began in Hollywood, where the headlines were. And the stardust.

9. Ben is the son of a German film director and his brother had close ties to German émigrés. What made you introduce so many Germans into a Hollywood story?

Actually, the Germans came first. I was originally drawn to Los Angeles as a setting because of the extraordinary group of German refugees who ended up there—a phenomenon still very little known, even in Los Angeles itself. Hollywood had always been a magnet for talent from the German film industry, especially in the 20s and early 30s, when the move was motivated by career opportunities or family ties, as well as politics. F. W. Murnau, Ernst Lubitsch, Fritz Lang, William Wyler, Billy Wilder, Peter Lorre, Marlene Dietrich—a long list, all early arrivals.

The Germans who came later were somewhat different, an increasingly desperate group of exiles, part of the European intellectual diaspora that was Hitler’s inadvertent gift to America. In a sense, this was for me a continuation of The Good German. That had been a book about a city utterly devastated by war, both physically and morally. But what about the people who had been lucky enough to get out? I was particularly interested in the group that went to L.A.—whether for the climate, the cheaper cost of living, or hopes of finding work in Hollywood—because of the great cultural dislocation L.A. represented in their lives. This was a city, after all, that even most Americans at the time considered exotic, a sunny Eden. Imagine its impact then on the émigrés, often representatives of high culture, who had literally just escaped with their lives, sometimes a few steps ahead of the Gestapo, and now find themselves in a world of palm trees and swimming pools and milkshakes, and a popular culture largely indifferent to them. This seemed to me a story rich in dramatic possibilities, especially since, as technically enemy aliens, they were subject to FBI surveillance (and hounded for any leftist sympathies), the very kind of political intimidation they’d left Germany to escape.

The émigrés are still very much a part of Stardust but book ideas often grow in ways you don’t quite expect and as the story went along I began to see that the Germans were only a part of the larger story, that what they really offered me was a way to look at Hollywood from a different angle.

10. In Stardust you combine history and storytelling to weave your tale. What plotlines or characters from the book are historically based, and which are your own inventions?

The major plot lines, the murder, the motivation for it, the love story, are all invented. Only the background is historically based. But of course the background is an important part of this book and it needs to be as accurate as possible to make the fiction plausible. None of the principal characters are intentional composites or stand-ins for anyone real, except possibly Kaltenbach, who was inspired by Heinrich Mann. Some real people do appear—Paulette Goddard, Jack Warner—but they are only real in the sense that this is how I imagine them to have been. You listen to their voices in memoirs and anecdotes (and of course film) and hope they sound that way here, but in any case these are minor characters in the larger story.

I have mixed feelings about using real people in fiction, in part because readers can bring their own sense of the character to the page and find yours inconsistent. In fact, this is the first time I have done so since Los Alamos--how could Oppenheimer have been anyone else? But celebrity is so important a part of the culture of Hollywood that some star-gazing seemed inevitable and I found that using real people could make a point about the ephemeral nature of celebrity itself.

I avoided enduring icons like Bogart. The movie people who appear here were certainly famous at the time, but perhaps not so well known today. At Lasner’s party Paulette, Ann Sheridan, and Alexis Smith all make an appearance (and dress up the party) but so does the fictional Rosemary, whose shining moment this is, and my hope was to make them interchangeable to the reader, Rosemary just as real as the boldface names—and now all of them faded. Real people also appear from the émigré community—Brecht, Feuchtwanger, Alma Mahler, etc—but again this is primarily to lend more plausibility to the fictional ones (Ostermann and Liesl). What isn’t made up is the mixed blessing of their exile, saved but not rootless in a town of strangers.

About The Reader

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Audio (September 29, 2009)

- Runtime: 6 hours and 30 minutes

- ISBN13: 9780743597944

Raves and Reviews

"Spectacular in every way...wonderfully imagined, wonderfully written, an urgent personal mystery set against the sweep of glamorous and sinister history. Joseph Kanon owns this corner of the literary landscape and it's a joy to see him reassert his title with such emphatic authority." -- Lee Child

"The new Joe Kanon is one of the best, Stardust is the perfect combination of intrigue and accurate history brought to life." -- Alan Furst

"Stardust is sensational! No one writes period fiction with the same style and suspense - not to mention substance - as Joseph Kanon. A terrific read." -- Scott Turow

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Stardust Abridged Audio Download 9780743597944(0.8 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Joseph Kanon © Chad Griffith(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit