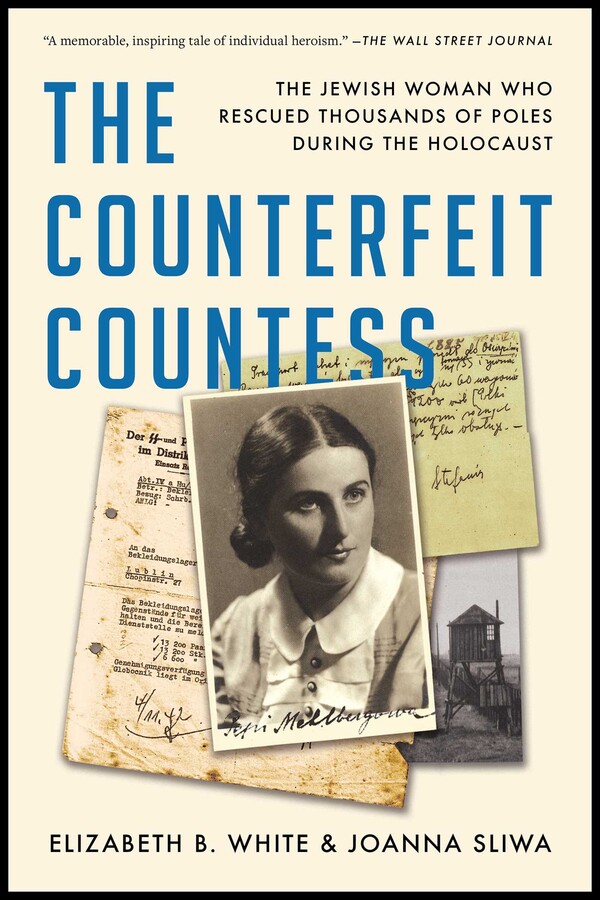

The Counterfeit Countess

The Jewish Woman Who Rescued Thousands of Poles During the Holocaust

By Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa

LIST PRICE $19.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

The “remarkable…inspiring” (The Wall Street Journal) true story of Dr. Josephine Janina Mehlberg—a Jewish mathematician who saved thousands of lives in Nazi-occupied Poland by masquerading as a Polish aristocrat—drawing on Mehlberg’s own unpublished memoir.

World War II and the Holocaust have given rise to many stories of resistance and rescue, but The Counterfeit Countess is unique. It tells the astonishing unknown story of “Countess Janina Suchodolska,” a Jewish woman who rescued more than 10,000 Poles imprisoned by Poland’s Nazi occupiers, becoming “a heroine for the ages” (Larry Loftis, author of The Watchmaker’s Daughter).

Mehlberg operated in Lublin, Poland, headquarters of Aktion Reinhard, the SS operation that murdered 1.7 million Jews in occupied Poland. Using the identity papers of a Polish aristocrat, she worked as a welfare official while also serving in the Polish resistance. With guile, cajolery, and steely persistence, the “Countess” persuaded SS officials to release thousands of Poles from the Majdanek concentration camp. She won permission to deliver food and medicine—even decorated Christmas trees—for thousands more of the camp’s prisoners. At the same time, she personally smuggled supplies and messages to resistance fighters imprisoned in Majdanek, where 63,000 Jews were murdered in gas chambers and shooting pits. Incredibly, she eluded detection, and ultimately survived the war and emigrated to the US.

Drawing on the manuscript of Mehlberg’s own unpublished memoir supplemented with prodigious research, Elizabeth White and Joanna Sliwa, professional historians and Holocaust experts, have uncovered the full story of this remarkable woman. They interweave Mehlberg’s sometimes harrowing personal testimony with broader historical narrative. Like The Light of Days, Schindler’s List, and Irena’s Children, The Counterfeit Countess is a “riveting…stunning” (Debbie Cenziper, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and author of Citizen 865) account of inspiring courage in the face of unspeakable cruelty.

World War II and the Holocaust have given rise to many stories of resistance and rescue, but The Counterfeit Countess is unique. It tells the astonishing unknown story of “Countess Janina Suchodolska,” a Jewish woman who rescued more than 10,000 Poles imprisoned by Poland’s Nazi occupiers, becoming “a heroine for the ages” (Larry Loftis, author of The Watchmaker’s Daughter).

Mehlberg operated in Lublin, Poland, headquarters of Aktion Reinhard, the SS operation that murdered 1.7 million Jews in occupied Poland. Using the identity papers of a Polish aristocrat, she worked as a welfare official while also serving in the Polish resistance. With guile, cajolery, and steely persistence, the “Countess” persuaded SS officials to release thousands of Poles from the Majdanek concentration camp. She won permission to deliver food and medicine—even decorated Christmas trees—for thousands more of the camp’s prisoners. At the same time, she personally smuggled supplies and messages to resistance fighters imprisoned in Majdanek, where 63,000 Jews were murdered in gas chambers and shooting pits. Incredibly, she eluded detection, and ultimately survived the war and emigrated to the US.

Drawing on the manuscript of Mehlberg’s own unpublished memoir supplemented with prodigious research, Elizabeth White and Joanna Sliwa, professional historians and Holocaust experts, have uncovered the full story of this remarkable woman. They interweave Mehlberg’s sometimes harrowing personal testimony with broader historical narrative. Like The Light of Days, Schindler’s List, and Irena’s Children, The Counterfeit Countess is a “riveting…stunning” (Debbie Cenziper, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and author of Citizen 865) account of inspiring courage in the face of unspeakable cruelty.

Excerpt

Prologue PROLOGUE

August 9, 1943

Lublin, Poland

Once again, the commandant of Majdanek concentration camp found Countess Suchodolska in his office, making yet another absurd demand.

SS-Obersturmbannführer Hermann Florstedt had served at several concentration camps in Germany, but Majdanek, he had found, bore little resemblance to them. Located in Lublin in German-occupied Poland, the camp was primitive and chaotic compared to the concentration camps in the Reich. Florstedt’s assignment as the camp’s commandant in 1942 had been a promotion, but also punishment for suspected corruption at Buchenwald. He had arrived at Majdanek to find a massive construction site with unpaved roads, no running water, contaminated wells, and open latrines that gave off an overpowering stench. Towering billows of smoke regularly belched from the camp’s crematorium chimney, raining down the ashes of men, women, and children murdered in the gas chambers. Currently 23,000 prisoners were languishing in unimaginable filth. Infectious diseases were so rampant that even the SS guards sickened and died.

Majdanek did have one compensation in Florstedt’s view: it was the repository of the personal belongings of many of the hundreds of thousands of Jews being murdered by the SS in German-occupied central Poland. SS warehouses in Lublin held mountains of clothes, shoes, furs, and leather goods, and boxes full of currency, jewelry, watches, wedding bands, and gold teeth. It was Florstedt’s responsibility to ensure that Majdanek prisoners processed these goods so that the SS could fully profit from them. But who would notice if Florstedt and his most trusted men took some of the riches as recompense for their service in plundering and murdering Germany’s racial enemies?

One of the vexations of Florstedt’s work, however, was the meddling of Polish aid organizations that sought to provide food and medicines for Majdanek’s Polish prisoners. The Polish Main Welfare Council and the Polish Red Cross were far more assertive than any similar organizations in the Reich. They had actually obtained permission to make weekly deliveries of bread and food products for the prisoners’ kitchens, to supply the prisoners with packages of food and necessities, and to provide medicines for the camp infirmaries. And yet Countess Janina Suchodolska of the Polish Main Welfare Council continually pressed for more: to make more frequent deliveries of more food and more medicines. She even proposed delivering prepared soup for the prisoners. Such things would be out of the question in any other concentration camp. But when told no, the Countess simply made the rounds of higher SS and Nazi authorities until she finally persuaded one that her requests were somehow in German interests.

To make matters worse, the Countess used her visits to Majdanek to spy on the conditions there. Efforts to deter her had proved fruitless. The petite brunette aristocrat remained utterly unflappable in the face of shouts and threats from the SS. Recently, she had even alerted health officials to a typhus epidemic among the prisoners, forcing Florstedt to arrange some semblance of treatment for them.

Now she was pestering Florstedt about the thousands of Polish peasants in the camp. The SS had dumped them there in July after evicting them from their farms to make room for German settlers. Since the SS quickly culled the able-bodied adults for forced labor in the Reich, the peasants still in the camp were mostly children or elderly. After just a few weeks in the camp, these prisoners were already dying of dehydration, starvation, and diseases at a rate that was extreme even for Majdanek. Somehow, the Countess had persuaded German authorities to release the 3,600 Polish peasants still on Majdanek’s rolls, but only on condition that her organization provided all the necessary paperwork and found places for them to live. In just a couple of days, Countess Suchodolska and her coworkers managed to do both.

The Countess had arrived at the camp gate in the morning to receive the civilians. There she was informed, with no further explanation, that nearly half of them were no longer “available” for release. The remaining civilians had been assembled in the third of Majdanek’s five prisoner compounds, about a kilometer from the gate where the Countess awaited them. The distance had proved too far for many to walk: the Countess had watched with increasing alarm as prisoners, trying in vain to hold each other up, stumbled, fell, and lay helpless in the dust. And so here she was in Florstedt’s office, insisting that he allow trucks and ambulances to enter the camp and pick up the prisoners. Allowing Polish civilian transport inside a concentration camp was in complete violation of SS security regulations! But Florstedt knew there was no point in refusing—the Countess would just go over his head.

Within two hours, trucks, buses, and ambulances arrived, recruited by the Countess from businesses and organizations throughout the city.

In the end, 2,106 peasants were released from Majdanek in August 1943. More than 25 percent of them wound up in Lublin’s two main hospitals, and nearly 200 died within days, over half of them children under age twelve. But some 1,900 survived, thanks to the efforts of Countess Suchodolska and her many colleagues.

Her efforts to help the prisoners of Majdanek did not end there. The Countess relentlessly pressed Nazi authorities for more concessions, and gradually they agreed to permit increased deliveries of food, medicines, and supplies. They even allowed her to bring in decorated Christmas trees so that the prisoners could celebrate the holiday. By February 1944, the Polish Main Welfare Council was supplying soup and bread five times a week for 4,000 Polish prisoners in Majdanek, in addition to other deliveries of food and medicine. The Countess herself usually brought the soup into the camp, under the close supervision of SS guards.

Throughout all her dealings with Nazi and SS officials, no one ever suspected that the indomitable Countess, so self-assured and aristocratic in her demeanor, was not a countess at all, nor was her name really Suchodolska. She was Janina Spinner Mehlberg, a brilliant mathematician, an officer in the underground Polish Home Army, and a Jew.

August 9, 1943

Lublin, Poland

Once again, the commandant of Majdanek concentration camp found Countess Suchodolska in his office, making yet another absurd demand.

SS-Obersturmbannführer Hermann Florstedt had served at several concentration camps in Germany, but Majdanek, he had found, bore little resemblance to them. Located in Lublin in German-occupied Poland, the camp was primitive and chaotic compared to the concentration camps in the Reich. Florstedt’s assignment as the camp’s commandant in 1942 had been a promotion, but also punishment for suspected corruption at Buchenwald. He had arrived at Majdanek to find a massive construction site with unpaved roads, no running water, contaminated wells, and open latrines that gave off an overpowering stench. Towering billows of smoke regularly belched from the camp’s crematorium chimney, raining down the ashes of men, women, and children murdered in the gas chambers. Currently 23,000 prisoners were languishing in unimaginable filth. Infectious diseases were so rampant that even the SS guards sickened and died.

Majdanek did have one compensation in Florstedt’s view: it was the repository of the personal belongings of many of the hundreds of thousands of Jews being murdered by the SS in German-occupied central Poland. SS warehouses in Lublin held mountains of clothes, shoes, furs, and leather goods, and boxes full of currency, jewelry, watches, wedding bands, and gold teeth. It was Florstedt’s responsibility to ensure that Majdanek prisoners processed these goods so that the SS could fully profit from them. But who would notice if Florstedt and his most trusted men took some of the riches as recompense for their service in plundering and murdering Germany’s racial enemies?

One of the vexations of Florstedt’s work, however, was the meddling of Polish aid organizations that sought to provide food and medicines for Majdanek’s Polish prisoners. The Polish Main Welfare Council and the Polish Red Cross were far more assertive than any similar organizations in the Reich. They had actually obtained permission to make weekly deliveries of bread and food products for the prisoners’ kitchens, to supply the prisoners with packages of food and necessities, and to provide medicines for the camp infirmaries. And yet Countess Janina Suchodolska of the Polish Main Welfare Council continually pressed for more: to make more frequent deliveries of more food and more medicines. She even proposed delivering prepared soup for the prisoners. Such things would be out of the question in any other concentration camp. But when told no, the Countess simply made the rounds of higher SS and Nazi authorities until she finally persuaded one that her requests were somehow in German interests.

To make matters worse, the Countess used her visits to Majdanek to spy on the conditions there. Efforts to deter her had proved fruitless. The petite brunette aristocrat remained utterly unflappable in the face of shouts and threats from the SS. Recently, she had even alerted health officials to a typhus epidemic among the prisoners, forcing Florstedt to arrange some semblance of treatment for them.

Now she was pestering Florstedt about the thousands of Polish peasants in the camp. The SS had dumped them there in July after evicting them from their farms to make room for German settlers. Since the SS quickly culled the able-bodied adults for forced labor in the Reich, the peasants still in the camp were mostly children or elderly. After just a few weeks in the camp, these prisoners were already dying of dehydration, starvation, and diseases at a rate that was extreme even for Majdanek. Somehow, the Countess had persuaded German authorities to release the 3,600 Polish peasants still on Majdanek’s rolls, but only on condition that her organization provided all the necessary paperwork and found places for them to live. In just a couple of days, Countess Suchodolska and her coworkers managed to do both.

The Countess had arrived at the camp gate in the morning to receive the civilians. There she was informed, with no further explanation, that nearly half of them were no longer “available” for release. The remaining civilians had been assembled in the third of Majdanek’s five prisoner compounds, about a kilometer from the gate where the Countess awaited them. The distance had proved too far for many to walk: the Countess had watched with increasing alarm as prisoners, trying in vain to hold each other up, stumbled, fell, and lay helpless in the dust. And so here she was in Florstedt’s office, insisting that he allow trucks and ambulances to enter the camp and pick up the prisoners. Allowing Polish civilian transport inside a concentration camp was in complete violation of SS security regulations! But Florstedt knew there was no point in refusing—the Countess would just go over his head.

Within two hours, trucks, buses, and ambulances arrived, recruited by the Countess from businesses and organizations throughout the city.

In the end, 2,106 peasants were released from Majdanek in August 1943. More than 25 percent of them wound up in Lublin’s two main hospitals, and nearly 200 died within days, over half of them children under age twelve. But some 1,900 survived, thanks to the efforts of Countess Suchodolska and her many colleagues.

Her efforts to help the prisoners of Majdanek did not end there. The Countess relentlessly pressed Nazi authorities for more concessions, and gradually they agreed to permit increased deliveries of food, medicines, and supplies. They even allowed her to bring in decorated Christmas trees so that the prisoners could celebrate the holiday. By February 1944, the Polish Main Welfare Council was supplying soup and bread five times a week for 4,000 Polish prisoners in Majdanek, in addition to other deliveries of food and medicine. The Countess herself usually brought the soup into the camp, under the close supervision of SS guards.

Throughout all her dealings with Nazi and SS officials, no one ever suspected that the indomitable Countess, so self-assured and aristocratic in her demeanor, was not a countess at all, nor was her name really Suchodolska. She was Janina Spinner Mehlberg, a brilliant mathematician, an officer in the underground Polish Home Army, and a Jew.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (January 21, 2025)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982189136

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Counterfeit Countess Trade Paperback 9781982189136

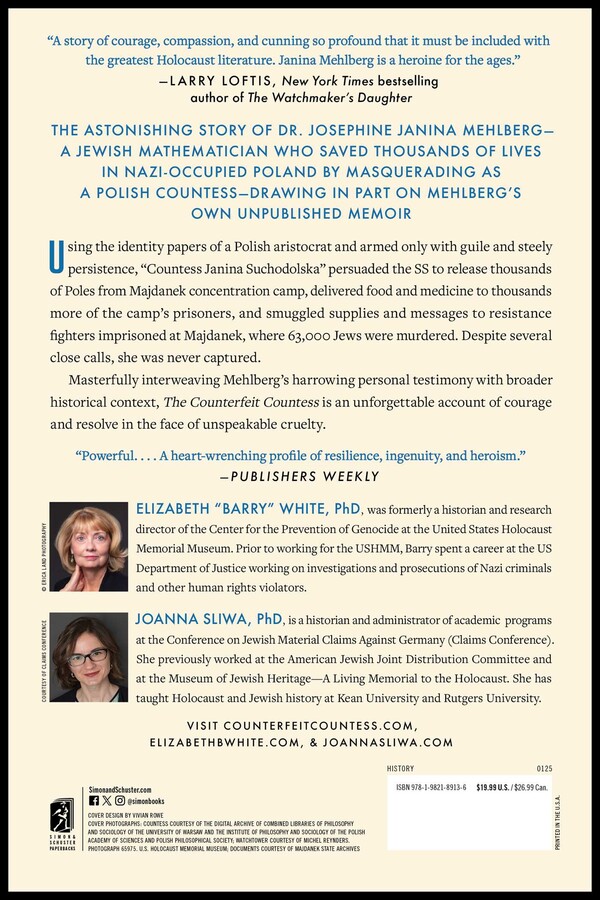

- Author Photo (jpg): Elizabeth B. White Photograph by Erica Land Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): Joanna Sliwa Photograph courtesy of Claims Conference(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit