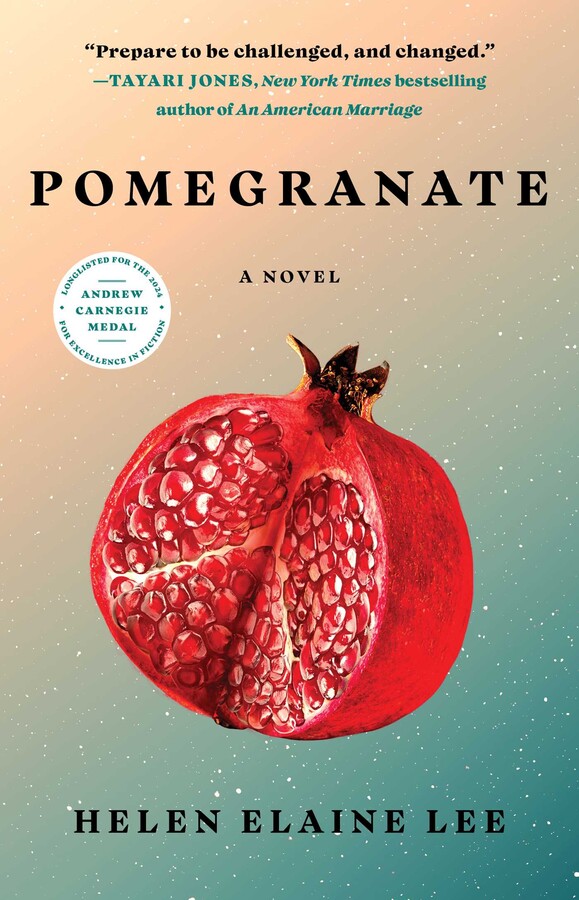

Pomegranate

A Novel

LIST PRICE $18.99

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

The acclaimed author of The Serpent’s Gift returns with this “deep and beautiful” (Jaqueline Woodson, New York Times bestselling author) story about a queer Black woman working to stay clean, pull her life together, and heal after being released from prison.

Ranita Atwater is “getting short.”

She is almost done with her four-year sentence for opiate possession at Oak Hills Correctional Center. Three years sober, she is determined to stay clean and regain custody of her two children. Ranita is regaining her freedom, but she’s leaving behind her lover Maxine, who has inspired her to imagine herself and the world differently.

My name is Ranita, and I’m an addict, she has said again and again at recovery meetings. But who else is she? Who might she choose to become? Now she must steer clear of the temptations that have pulled her down, while atoning for her missteps and facing old wounds. With a fierce, smart, and sometimes funny voice, Ranita reveals how rocky and winding the path to wellness is for a Black woman, even as she draws on family, memory, faith, and love in order to choose life.

Pomegranate is a complex portrayal of queer Black womanhood and marginalization in America from an author “working at the height of her powers” (Tayari Jones, New York Times bestselling). In lyrical and precise prose, Helen Elaine Lee paints a humane and unflinching portrait of the devastating effects of incarceration and addiction, and of one woman’s determination to tell her story.

Excerpt

February 2019

I live my life forward and backward.

Seems like my body remembers what I can’t afford to forget.

I’ll be carrying on, trying to choose right, and then the past comes for me, rumbling from my chest into my shoulders, pushing through my neck and up into my head. I try and answer its call, own where all I’ve been.

Remember, even when forgetting feels like the only mercy.

Four years of captivity, and here I sit on this hard plastic chair, surrounded by cinder block, about to leave Oak Hills. Waiting to be thrown back to the world. And I cannot get still. My knees jackhammer; my feet tap. They’ve got wills of their own. My interlocking fingers steeple and flatten and steeple.

I try and empty my mind, but my Oak Hills life thunders to the surface and flashes before me, like those shifting pieces of colored glass in the tin kaleidoscope I had when I was six. Damn, really? On my out day, which is stressful enough. I choose a pomegranate and try to see myself holding it, broken open, in my hands. Leathery skin. Pointy stalk. Jeweled seeds.

And I can just about feel the shape and weight of it again when I hear the shout, “Did I say you’re free to go?” and I’m surprised to find myself standing up. I look the overseer in the eye… why give him a name when all I am is inmate?… and rein in my anger as I sit my ass back down.

It’s true what they say about time slowing down the shorter you get. These last few days have inched by, me hoping and praying I’ve got it in me to keep doing right. I wait to get back the belongings I came in with, wondering what my stuff will look like to me now. Clothes that no longer fit. Cheap pleather purse full of what? Lip gloss. Suspended license. Empty wallet. Two keys that no longer open anything.

Dear God… dear Power Greater Than Me (whoever… whatever you are)… let me prove I deserve to be a mother to Amara and Theo. Let me handle my business, work my program, stay on track. Keep away from temptation, avoid the people who can pull me down. In here, meetings give you the fellowship that gets you through, and a place to say… to remember… you’re a human with a story that’s got a next chapter. Even if the confessing is excruciating, I’ll find a meeting and go every day if I have to.

Own being powerless and powerful.

Choose right.

Behind the walls, in this concrete desert, everything’s regulated and decided for you. All the everyday stuff, the whats and the whens. Wake up and go to chow. Get your meds. Go outside and come back in. Take a shower. Go to sleep. Line up for this. Sit down and wait for that. And all those things that on the outside you do and pay no attention? Behind the walls they’re the high points of your day. Makes me feel like that German shepherd of Jasper’s. He named him King and kept him in a chain-link corridor. Nobody ever played with him or loved on him. He lived to eat.

Buff that floor. Scrape those plates. Sew labels into these T-shirts, one after another and then some more, and sew American flags for the folks who hate your kind to jab you with. Improve yourself with classes and groups.

All day long you’re told what and when and how, and the cost of defiance, too. And you hear the echoes of ancestors, whispering that though the best chance of survival may be submission, that could also be the death of you. And love… affection… touch… the stuff that makes your heart keep beating? Contraband. Now who, I ask, can keep alive that way?

Nothing much grows in here unless you go hard against the script. To keep alive, you’ve got to choose what you can, small though it may seem. Imagine yourself past the razor wire. Notice those trees and birds way in the distance. Look at the sky and picture it whole. You’ve got to see yourself free from the demon that rides you, believing something new, something clean, can happen, after all. Behind the walls, nothing’s small. And choosing, it’s something precious, and it means life just might have some mystery in store for you.

I choose you, Maxine once told me, and you’re against the rules.

Yesterday, at the end of my little leaving party, I stood there as she left the dayroom before me. All of my well-wishers were there. Gwen and her latest boo. Avis, crocheting her endless blanket. Eldora and the family she builds and mothers in here. Even my new cellie Keisha came, though she still thinks she can do her time solo. We ate the makeshift treats and canteen snacks they all chipped in, and everyone said what they’d do if it was them getting out. And when it was over, I watched Maxine’s proud, upright back fade away.

Tender-tough Maxine. Along with her free-world walk and the way she breaks down the politics of just about everything 24/7, her ink and her no-nonsense way and her legal know-how, there’s a world of other stuff inside. She can talk up pomegranates and make me taste them. She can conjure grass or clouds or cornfields, tell Chesapeake riverbanks and make me feel the current and the muddy floor.

I wanted to run after her, call out to her, touch her. I love that back, that’s what I was thinking. Its moles and scars. Its tats. Its defiant pride, no matter what she’s been through. Like most of us in here, the only sleep she knows is broken.

Last night, I sat in my cell with the card everyone signed and the little in-spite-of gifts from the leaving party, so sweet and painful, and started counting down the last bit of time I owed.

I could feel Keisha’s crying shake the bunk above me. Mostly we look away to give a little privacy. This time I stood and asked, “You alright?” Like usual, she didn’t answer. I’d seen her with a letter earlier and figured it must have been the kind that tells you something bad, maybe the kind that says you’ve been foreclosed.

I made my voice as gentle as possible. “Word from home?”

She sat up, pulled the envelope from the covers, and ripped it up. Then she threw the pieces to the floor, oozing angry and bitter, and said, “Where the fuck is home?”

I didn’t even know what to say to that. Maybe it’s a good question for most of us in here, but I couldn’t answer and I couldn’t just go back to my bunk, so I stood there looking at the photos she’d stuck up on the wall with toothpaste. And I knew it was risky, but there’s one sure way to get a woman to open up.

“That your baby girl?”

She nodded, wiping her eyes with her sleeve. “Tyeisha. She’s almost three.”

I was relieved. Pained, too, I’ll admit it, when she said, “She’s with my moms.” Some folks have mothers beside them through their thick and thin. Then I asked about her girl. Keisha kept her answers short, but I saw a light in her eyes come on. “She knows her letters and numbers. Her favorite color’s green.”

She jumped down from the top bunk and walked across the torn pieces of her letter to get to the stingy window where she likes to stand, looking out at the sky. Something in me wanted to make her face reality, tell her even if she could find the drinking gourd up there, she wouldn’t be following it to freedom. And part of me wanted to hug her to me like she’s one of mine. But I’m out of here tomorrow, I reminded myself, getting my feelings in check as I turned away.

Trying to ignore her, I got ready to rise up and go, come morning. Took my hair out of the cornrows I’ve been wearing these last few years, thinking on how I tripped when I first got here. No relaxers. No extensions. Barely any hair products at all. Easiest thing to do is either learn to braid or figure out something you can trade to someone who knows how, turn in your weapons, and forget about cute. I sat on the edge of my bunk, picking out my braids with the end of my comb, and it felt good as I freed up my hair, though when it was all loose I couldn’t help thinking how Mama would have shut her eyes to the sight of me either way, cornrows or my wild kinks, and did my best to smooth it back into an Afro puff.

I gathered up my worldly possessions, starting a pile on my bunk. Laid out my second-string beater sneakers, T-shirts, socks, two of the unsexiest bras you ever saw, and a week’s worth of high-waisted gray cotton underwear you can’t really call panties. Comb and hair grease. Wounded dictionary. I unfolded the loose-leaf paper Eldora pushed into my hand today and my eyes teared up as I looked at what she’d shared with me from last summer’s garden plot, though she had so little to spare: pale discs from her bell peppers and zucchini seeds, smooth and eye shaped.

I’d already returned everything I’d borrowed from the donated library that made up the one cubic foot of reading and writing material allowed, and passed on my flip-top tuna and ramen noodles. Traded envelopes and paper for extra socks. Put aside my extra toilet paper for Keisha, along with the little bars of soap that made me itchy and ashy. Tossed my shower flip-flops. And that was it, what I had to show for my Oak Hills life. I was already wearing my good sneakers, my thermals, and the windbreaker that passes for a winter coat.

Looking at my list of Boston-area NA meetings before adding them to the pile, I tried not to be cynical about the names: Freedom Express… Clean and Proud… The Solution… South End Miracles. I read through the affirmations I’d put on index cards, remembering how embarrassed I was at first by their corniness, certain that Jasper was having a good laugh at them, at me, from the afterlife. The cards and letters and artwork from Amara and Theo. The program from Daddy’s funeral service. And the kites Maxine’s left for me over the last two and a half years. I keep that cache inside the Bible a missionary prison volunteer gave me. The little paper messages that gave me and Maxine another way of touching, and added some mystery and discovery to a world of regulations and taboos.

No sacred space in here except the ones we create, we made do and left them behind the dayroom microwave, where even if they were found, they could not be tied to us. Milagros. To be added to the free things list we make out loud, and the one I keep on my own.

Maxine got me plugged into recognizing and naming the things that cost nothing and don’t depend on permission, the things available to everyone, present and past tense. Future, too, one hopes. The smell of new-cut grass. Skipping stones. A curl of white birch bark. Eyelash kisses. Reading. Looking. Walking, even if it’s only round and round the Yard.

Next I added my notebook log of everything I did to keep in contact with my kids. Once I got my balance, I started putting it all down: every phone call; every card and letter; every visit Daddy, Auntie Jessie, and Auntie Val made here with them; every call to the caseworker, whether it got answered or not; every paper filed with DCF.

Then I pulled their photos off the wall, trying not to be vexed by the curled, worn edges, and spent some time with each one. The baby pictures, school photos, backyard snaps, and the one we posed for during visitation one year in, with the tropical beach background. Amara’s 13 now and Theo just turned 8, and it’s six months since I’ve seen them. Like always, I saw how much Amara looks like me, and wondered how hard that’s been. People used to say, Girl, you spit her out, and I’d smile, like it was some kind of trick or spell I’d managed, while hoping things would turn out different for her. Same wide nose. Same full lips I got from Mama, who told me I could learn to hold them in and “minimize” them, like she had. They got me teased when I was little and cruised before I was even grown. Same freckles and eyes that shift from green to brown, depending on who knows what… my contrary mood, that’s what Mama said… mud with a bit of algae, in my opinion, though I’ve heard them called by fancier names.

Black folks, we’re still obsessed with eyes and skin color and hair, and all my life people have either praised my eyes or decided I think I’m the shit for having them. Whatever. It’s not like I went to Walmart and picked them out. We all know what they come from: Ownership. Possession. Rape. Anyway, I hope Amara uses hers for seeing.

In Theo’s face, like always, I saw Jasper. He’s got his father’s sharp nose, which people love to focus on… dark, but keen featured, Mama would say… and his deep plum skin, instead of the russet brown of mine and Amara’s. Like Daddy’s, his eyes are dark and sparkly. But sometimes when I look at my boy I feel like his father’s still among the living, and I work at recalling what drew me to him, the pluses, instead of the minuses.

Wondering just who my kids are now, and what it’ll take for them to forgive me, my heart started banging around, and I laced my fingers together to stop them from shaking, then fished my cards from the pile to play some solitaire and thought some love over to my kids across the miles.

I pictured my boy, tender and easy to cry, asking his nonstop questions. What are dogs feeling when they bark? Why aren’t the double o’s in “look” and “loon” pronounced the same? Why are leaves green? And Amara, asking whether thinking you can do something makes you better at it, why her teachers talk down to the students in her class, whether a family is something you’re born into or something that’s decided. I hope Val and Jessie at least try and answer the questions about facts. How far away are the planets? What do you call a dolphin’s tail? I know the harder ones are the problem. What does “mother” mean? Which fights are worth it? How can you tell where you belong?

Keisha left her post at the window and climbed back up. She went still, slipping under, and I closed my eyes. Sleep would be hard to come by, and I prayed to get through one last night and morning without a shakedown storm.

Heartsick at losing Maxine as I gained my freedom, I tried to focus on the blessing of having been with her at all. And then I named what I was grateful for, moving from macro to micro. I had someone who’d loved me right. People on the outside who’d never stopped showing up. Children I could still earn back. One thousand one hundred and fifty-nine clean days, but who’s counting? A novel I’d just finished that was echoing through me. Trees that would soon be in reach. And the photo of Amara, torn down the middle by a shakedown boot heel, had survived. I had mended it, and here it was, on the pile right beside me.

Out loud, I said, “I don’t know their favorite colors,” speaking to I-don’t-know-who, just trying to get a sounding in the big, wide dark. I expected no answer from Keisha and got none, but I could hear her breathing and it was a comfort, that thread of body music just above my head.

Then morning came. The sky faded to stubborn gray. The lights came on and the morning noise kicked off, and when they hadn’t come to set me free I went to chow and couldn’t eat a bite. Looked for Maxine, but she didn’t show.

Two COs came for me soon after, barking orders to get my things and come with them. Like usual, they looked at me like I’m trash, even though the places they come from were at least as shitty and broken as the ones that grew most of us in here, even though they and theirs know the same rung where we’ve bottomed, turnkey being the other path out of the basement so many of us know.

And now I’m waiting to be told I’m free to go.

I stop trying to call up my pomegranate. It’s gone, for now. So I start my silent chant: Get to Auntie Jessie’s. Meetings. Job. My own place. My kids. I can do it. I’m never coming back.

My two aces are my aunties. Daddy’s baby sister, Val, she got a job in Boston and moved here to help. Since he died she’s been carrying the whole thing by herself. The house, the kids, they’re off-limits to me. And she’s in charge.

And big sis Jessie, she’s letting me crash with her for a couple months, even though she just got out of the rehab from her stroke. I can stay until my cousin Gil gets back from Afghanistan, where the warring never seems to end. Jessie, she stood by me when I screwed up, disappeared, relapsed. Until she didn’t.

She drew a hard line with me, but she kept on showing up for Amara and Theo. And once I had 30 days clean, she came to visit, along with Daddy and the kids. Sent me cards and photos and novels from Amazon. Put money on my books, adding to my 72-cents-an-hour “job” doing laundry, cleaning, flag sewing, kitchen work, minus the half taken out for forced savings and the deductions for medical fees, account activity fees, disciplinary violations. Jessie said she’ll give me shelter, and I know the deal. Long as I’m working my program, I can stay.

Soon as they say so, I’ll be walking through the gate, a year since they let me out to say good-bye to Daddy. Wake or funeral, I had to choose and picked the former, unsure I could keep my shit together for the funeral, arriving in church with escorts, everyone’s eyes on me. At least I had a few quiet, private minutes with Daddy during the viewing at the funeral home. Soon, when I can bear it, I’ll visit his grave.

Looking at him lying in his coffin, I thought he seemed peaceful, unburdened. Unlike Mama, who seemed to still be raging, still saying no to me. Now I’ve lost Daddy, who said yes even when he shouldn’t have.

I was swamped by sadness as I stood beside his body, and by anger, too, the general kind, at all the things: the world, the way things work, the “carceral state,” my lot. And at Daddy, too, I admit it, for leaving me. Before I walked away from his casket I closed my eyes and imagined slipping my two-year sobriety chip into the pocket of his suit.

Jessie and Val were standing at the door to the viewing room, exhausted. Wrecked. Greeting the neighbors and friends from work and church who filed in, and at least I was spared making small talk about what felt like the end of the world. Amara and Theo sat together in the corner, looking numb and out of reach, blaming me, no doubt, for taxing Daddy till he broke. I hugged them, but their arms hung limp. They were going through the motions with me. Daddy, the backbone, he was the hard loss.

The aftershocks still hit, and the sadness body-slams me again and again, just when I think my mourning is done. Feels like a part of me now, like the rainy-weather ache of a mended bone. We’re all still standing, but I can’t help worrying about the TPR law. Termination of Parental Rights, if you can believe that, and if that ever does go down, I’ll be thinking on joining Daddy, and I know ways, fast and slow, to do that.

I get $75 gate money in cash and a check for the $264.57 in my account, and peek in the bag they give me, the stuff I came in with four years ago. I keep the keys and throw the purse in the trash. It’s winter in America, I’m making a new start, and along with the windbreaker they let me keep, my lightweight sweats and T-shirt will have to get me home. They show me where to change and I force my expanding hips into them, then return my DOC scrubs, grab the bag with my belongings, and hold on tight to my release sheet, my hands shaking so bad the papers flap like white flags: Okay, I still surrender. Whatever you say still goes.

I try and imagine myself singing, but seems like that’s over. Lost in the crash that landed me here.

I try and see myself down the road in my own cozy apartment, but the hallway’s as far as I usually get. I try to forget the room where I last holed up, tornadoed with covers and clothes, unwashed dishes and pizza boxes and the bitter, vinegar smell of cooked-up drugs. And if I’m not careful with my imagining, my before blocks out everything that might could happen, pushing it all together into a shakedown pile, and I’m in the middle, yelling, Remember me? There’s a sista in here, trying to breathe her way into tomorrow. Remember me?

I stand up, like I’m told. And as I approach the gates, the CO who’s opening them up gives me a last bit of scorn: “Hasta luego; see you back here soon.” I throw some shade his way and walk through. And here it is, what I’ve been wanting and fearing. Freedom.

Reading Group Guide

Introduction

Ranita Atwater is “getting short.”

She is almost done with her four-year sentence for opiate possession at Oak Hills Correctional Center. With three years of sobriety, she is determined to stay clean and regain custody of her two children.

My name is Ranita, and I’m an addict, she has said again and again at recovery meetings. But who else is she? Who might she choose to become? As she claims the story housed within her pomegranate-like heart, she is determined to confront the weight of the past and discover what might lie beyond mere survival.

Ranita is regaining her freedom, but she’s leaving behind her lover Maxine, who has inspired her to imagine herself and the world differently. Now she must steer clear of the temptations that have pulled her down, while atoning for her missteps and facing old wounds. With a fierce, smart, and sometimes funny voice, Ranita reveals how rocky and winding the path to wellness is for a Black woman, even as she draws on family, memory, faith, and love in order to choose life.

Perfect for fans of Jesmyn Ward and Yaa Gyasi, Pomegranate is a complex portrayal of queer Black womanhood and marginalization in America: a story of loss, healing, redemption, and strength. In lyrical and precise prose, Helen Elaine Lee paints a humane and unflinching portrait of the devastating effects of incarceration and addiction, and of one woman’s determination to tell her story.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. The first line narrated by Ranita is: “I live my life forward and backward.” How does this line announce a central theme of the novel and relate to its structure?

2. Upon Ranita’s release from prison, she resolves to remain sober and repair her relationships with her children. What obstacles did you predict Ranita would face? How did they differ from what she experiences in the novel? How does her freedom entail both empowerment and obstacles?

3. After she gets out of Oak Hills, how does Ranita navigate her encounters with Auntie Jessie, Auntie Val, Judy, Vera, Leon, and David Quarles? What roles do these interactions and evolving relationships play in Ranita’s journey?

4. Ranita is mandated to meet with a psychotherapist and a caseworker as part of her push for family reunification. What do her encounters and relationships with those figures reveal?

5. In Chapter 10, Ranita tells Drew Turner, “I have been loved right. Once.” What made her relationship with Maxine feel right to her, and what distinguishes it from her previous relationships with Jasper and David Quarles?

6. Maxine offers Ranita a series of kites with questions during their unfolding relationship at Oak Hills. What do these questions reveal about Ranita and Maxine’s relationship?

7. What insights did Ranita’s story give you about incarceration and the experiences of people within the criminal justice system?

8. How does Ranita navigate her shame regarding her addiction, her incarceration, her childhood, and her mothering?

9. How is Ranita’s mothering affected by her relationship with Geneva? What distinctions and similarities do you see in these relationships? What kind of mother does Ranita strive to be?

10. How do Ranita’s engagements with psychotherapy, speculation, and dance develop over the course of the novel?

11. How do Ranita’s feelings about her queerness change over the course of the novel?

12. What are some of the things Ranita realizes about love as the novel develops and concludes?

13. What inner strengths does Ranita have that will help her to navigate difficulty? What is important about her memory of going out into the rain that is captured in Chapter 32?

14. How would you characterize the journey Ranita makes in this novel?

15. What do pomegranates represent in the novel? Does the meaning of the pomegranate that was gifted to Ranita by her father change for her over the course of the novel?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Create your own messages and challenges, like the kites Maxine and Ranita make for each other while at Oak Hills. Offer your own questions that you believe will help reveal inner truths, trade them with partners, and respond.

2. Music and dance are refuges for Ranita throughout the novel. Create your own playlists of songs that help you release and offer comfort and share them with the group. If you’re comfortable, try dancing to a few songs and talk about how the music makes you feel.

3. Books are also a refuge for Ranita. What books have brought you joy and helped you through hard times?

4. Being in tune with the ordinary beauty around her and continuing the “free things list” she made with Maxine help sustain Ranita. How do you engage in this kind of practice and how does it make you feel? What would you put on your own free things list?

5. Pomegranate offers an intimate look into life within prison, including the horrors, the sisterhood, the disruption of families. Discuss the different portrayals you have read and seen about life in prison, and how they compare to the depictions in Pomegranate.

A Conversation with Helen Elaine Lee

When did you first find the inspiration for this novel?

I’ve always been compelled by the questions of how people pull light from darkness and how we renew and reinvent ourselves. And in everything I write, I’m exploring remembering, the role of narrative in our lives, and how we keep alive despite deprivation.

My interest in the lives of people who are incarcerated was instilled in me by my father, who was a criminal defense attorney. He taught me that everyone has a complex and important story, that many people grow up without love or opportunity or choices, and that justice is a fiction for some of us. And the people he represented were not invisible to me as I was growing up. Their lives were connected to mine. Because of the urgency of the injustice of mass incarceration, I wanted to write about it. And although a lot has been written about it from an academic distance, fiction has the potential to move readers past fear and indifference to feel the lived and emotional truths of addiction, imprisonment, and recovery.

It’s the role of the fiction writer to imagine lives other than her own. But I count those who have been imprisoned as my people, and I feel a responsibility to use the access and privilege I have had to speak. Still, I have not been incarcerated, and although I didn’t know for a couple of years what shape it would take, I knew I needed to try to “earn” the story I might be able to tell. I began to volunteer, twenty years ago, by leading creative writing workshops for people who were locked up in a county house of correction, and then in a medium-security prison and a prerelease facility through a program I helped to establish with PEN New England.

In those workshops, I was transformed by what people had endured, by the survival of dignity, by the practice of divining what has mattered in our lives. I was moved by the self-interrogation and generosity I witnessed. Writing is an act of recovery and power, and for those writers behind the walls, telling their stories was an assertion of visibility, of meaning, of humanity. And I’m indebted to those participants, and to others whose lives were touched by incarceration, for the stories they shared with me.

What else did you draw on to write Pomegranate?

I volunteered, interviewed people who had been incarcerated and their family members and people who had been in community with them. I read and watched films and talked to people and worked with people to try to educate myself about various aspects of the novel. And I drew on the personal. Loved ones pained by addiction and abuse. My own story of mothering, and daughtering, and family. My understanding of the ongoing roles and intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality in our lives. My experience of queerness and queer communities. What I know about the tensions between fierceness and sensitivity, belonging and marginality, the struggle and recompense of speaking out. I drew on my experience with the mandate to carry on. The healing forces of narrative and nature. The ways in which the present is burdened by the past. Really, it felt like I drew on everything I have been and done, everything in my pomegranate heart, to write this book.

Both within the jail and outside of it, Ranita is supported by those in community with her. What is the importance of community in this novel?

Community . . . fellowship . . . solidarity . . . are necessary for overcoming addiction, depression, trauma, the dehumanization and deprivation of incarceration, adversity, and oppression of all kinds. And in the most basic sense, humans need both connection and autonomy. Resistance through collective action, imagination, and expression has been critical to Black survival. By these means we have persevered through enslavement, diaspora, struggles for civil and human rights, racial terrorism, and state violence . . . through the panoply of historic and contemporary injustices. Collective action and solidarity have been critical to struggles for racial, economic, gender, and sexual justice, and intersectional belonging that honors our multiple experiences and identities is also necessary for surviving and thriving.

Ranita is deeply tied to Black people and Black women, through experience and history. She is tied to family, through which the story of who we are is passed, made and remade. None of those things, though, is without complexity. Disabling codes of masculinity and femininity, for example, shape the characters, as do destructive beauty standards. Geneva’s silence about her family history, which constitutes a wounding rupture, is shaped by racism and patriarchy. I wanted to show the power of community, but to get beyond mythologizing cultural inheritance and romanticizing belonging. After all, as Toni Morrison shows us so beautifully in her novels, community is both inclusive and exclusive. It has the power to wound and heal.

Ranita has had a kind of community of women of color at Oak Hills. And she has had a recovery community, though she has some inner conflict about fitting there. She is struggling with where she is welcome and where she belongs in various ways, and especially in terms of faith and organized religion, and in terms of queerness. She is struggling with the degree to which belonging and being loved mean being known. And with the balance between group affiliation and autonomy. By the end of the book, she begins to resolve some of these questions, but they are lifelong efforts for all of us.

Flashbacks in the novel reveal important moments of Ranita’s life and offer readers context into how she arrived at her current situation. Why did you choose to structure the book this way?

I came upon the structure, with the help of an editor, as I grappled with how to reveal the aspects of the past that inform Ranita’s struggles with addiction. I tried different strategies and ultimately found that the way the alternation between first-person present tense and third-person past tense allowed us to hear Ranita’s story as she is living it, in her own voice, and also to gain insights into her story that are beyond her understanding, or her memory, or about which she is just coming to awareness. The third-person omniscient narrator gives us pivotal moments in Ranita’s story from her point of view, but also sees more broadly and deeply. Together, they tell a fuller story than either one could alone.

The mother-daughter dynamics of this story were fraught and complex. How did you come up with these dynamics?

I think writers are often interested in imagining the things we have not experienced. I had a very warm and loving mother, and we had a close relationship until she died at ninety-four. She was a literature professor . . . a Black woman pioneer . . . and she gave me stories and books to see by. She was there for me always. She helped me raise my son. And she believed in me, as a person and a writer, even when I doubted myself.

So, I sought to imagine what it would be like to have the opposite kind of mother. For Ranita, I was imagining what kinds of wounds are disabling and lead to disempowerment and addiction. Her feeling that her mother has invalidated her emotionally is devastating. And Geneva’s transmission of shame about the body and its appetites has a profound effect. But I also wanted to portray Geneva as complex, in her own right and in terms of how Ranita perceives her. She is a product of her individual and family experience, societal values, and cultural inheritance. Indeed, we often pass down the things that have hurt us.

I wanted to explore how Geneva had been shaped by a racist and misogynist and classist society, looking at the force of respectability politics and the complexities of self-rejection in terms of race and gender and class. There are hints at her own thwarted dreams, her buried trauma, and her misguided efforts to toughen up Ranita, which instead demean and disable her. Black women continue to receive the message, from family and institutions and social context, that we are both too little and too much. And I am familiar with that double bind.

Ranita’s experience with therapy allows her to resurface repressed childhood memories. What did you want to show readers about therapy?

Although there has been understandable resistance to psychotherapy among Black people, it is possible to interrogate our stories and make a journey of self-examination, awareness, and healing, with the guidance of a psychotherapist who is trustworthy and compassionate and insightful. I wanted to show that uninterrogated suffering festers and is passed down. And that through being able to speak and feel the things that have been bounded by silence and shame, we are sometimes liberated and able to access and celebrate powerful and generative parts of our lives and ourselves that have felt inaccessible.

Maxine often speaks on the justice system and how society works against Black women, exemplified by Ranita’s experience in and outside of jail. How does Blackness permeate Ranita’s experience of finding freedom?

In my experience, the intersecting and interacting forces of race, gender, sexuality, and class do permeate our lives. These forces shape our every experience. I am never unaware of my experience as a Black queer woman who has had educational and economic privilege, but is, in the broader sense, still marginalized and doubted, no matter what threshold I’m crossing. I also feel that as I cross, my people, my ancestors are with me. But I didn’t consciously say to myself, Now I’m going to show how this works. I just wrote out of what I experience and understand about the world.

You seem interested in the role of the body in your characters’ lives. What did you have in mind with this thematic thread?

I wanted to explore how Black women’s bodies are contended territory through which control, personal and societal, is exercised. And I wanted to examine how the struggle between freedom and domination continues to play out through our bodies. How social and cultural conceptions of our bodies shape our experiences. How our bodies cannot be denied. How they keep records of our lives. And how, from enslavement to incarceration, we have had to manage being reduced to bodies, being denied the basic things that bodies need, remaining embodied and insisting on corporeal pleasure and joy, and sometimes psychically leaving behind our bodies, in order to survive.

I wanted to ask how we are shamed and silenced by being looked at, but not seen. How we are shaped by being scrutinized, desired, measured, feared, stereotyped, eroticized, mythologized, reduced. And how we can reclaim our bodies and our vision and our voices.

How did you decide that the pomegranate would be such an important item in the novel? Why the pomegranate and not another fruit?

Well, it’s funny, but my first novel also begins with a gift of fruit. In that case an orange, which embodies the duality of sweet and sour, is given at a time of running from family violence and being offered refuge. And somehow, I didn’t realize while writing Pomegranate that I was articulating the theme of loss and receiving in this way again.

By chance I was offered the pomegranate as a symbol of the precious and rare act of choice during imprisonment, by a friend who was incarcerated. I started off being compelled by that idea, and by the plain exterior of the fruit belying the striking jewels within. As I wrote and rewrote, it gathered meaning and came to resonate in multiple ways over the course of the story. It is the gift given with love and generosity during a time of loss. The possibility of wonder beneath the surface. The unexpected discovery from an unexpected source. It is a mythic symbol of fertility, prosperity, and more in many cultural traditions. In its spongy membrane Ranita sees the seemingly ordinary acts of carrying on that bind our lives and communities together. It is the heart that houses what is precious. The acceptance of our full and complex stories.

Product Details

- Publisher: Washington Square Press (January 30, 2024)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982171902

Raves and Reviews

"An aching portrayal of a woman whose young life gets waylaid by self-splintering challenges: abusive mother, wrong boy, debilitating addictions, grievous betrayals."

– Booklist

“A slow-burning, bittersweet novel of recovery, repair, and familial love.”

– Boston Globe

“A bold novel…[and] a complex, layered illustration of the effects structural racism, patriarchy, marginalization and violence can have on queer Black women throughout the U.S.”

– Ms. Magazine

“A raw, beautiful story of reintegration and a mother trying to do and be better for her kids. Oscillating between present-day Ranita and her past self, this story paints a real, painful picture of a woman caught in a cycle of drug use and eventual prison time, and her daily fight for sobriety and wellness when she returns to her family.”

– Southern Bookseller Review

“Lee writes beautifully about the healing power of Black kin networks, queer love, community support systems, and literature.”

– Buzzfeed News

“With a light, poetic touch, Lee balances the painful details of Ranita’s reality with genuine, persistent hope for new beginnings. It’s irresistible.”

– Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Like the pomegranate of the title…filled with unexpected treasures. Lee has created a powerful, beautifully written story of a woman who painfully confronts her past to build her future.”

– Booklist (starred review)

“Lee’s handling of trauma is deft, and her portrayal of the carceral system’s cruelty is unflinching and empathetic…a cache of jewels.”

– Kirkus Reviews

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Pomegranate Trade Paperback 9781982171902

- Author Photo (jpg): Helen Elaine Lee Photograph by Mark Ostow(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit