Our American Friend

A Novel

LIST PRICE $17.99

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

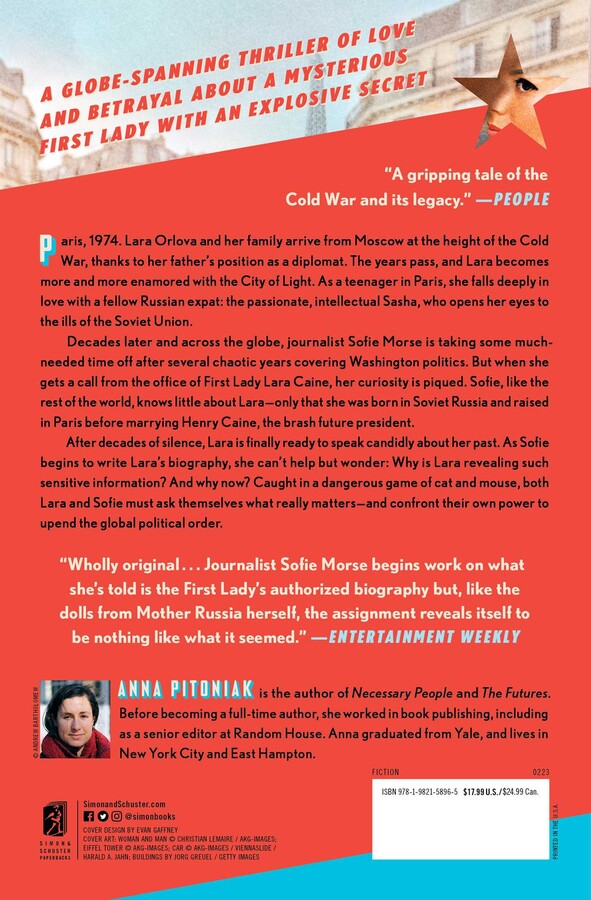

Paris, 1974. Lara Orlov and her family arrive from Moscow at the height of the Cold War, thanks to her father’s position as a diplomat. The years pass, and Lara becomes more and more enamored with the City of Lights. As a teenager in Paris, she falls deeply in love with a fellow Russian expat: the passionate, intellectual Sasha, who opens her eyes to the ills of the Soviet Union.

Decades later and across the globe, journalist Sofie Morse is taking some much-needed time off after several chaotic years covering Washington politics. But when she gets a call from the office of First Lady Lara Caine, her curiosity is piqued. Sofie, like the rest of the world, knows little about Lara—only that she was born in Soviet Russia and raised in Paris before marrying Henry Caine, the brash future president.

After decades of silence, Lara is finally ready to speak candidly about her past: about her father’s work for the KGB and about her ill-fated relationship with Sasha—which may be long in the past, but which could have explosive ramifications for the future. As Sofie begins to write Lara’s biography, she can’t help but wonder: Why is Lara revealing such sensitive information? And why now? Caught in a dangerous game of cat-and-mouse, both Lara and Sofie must ask themselves what really matters—and confront their own power to upend the global political order.

Excerpt

The Mediterranean was a deep winter blue, cold and dimpled like hammered steel, on the morning that I began wondering if I had made the worst mistake of my life.

The night before, I’d been walking home through our quiet corner of the city, no more or less nervous than usual. Light flickered from the dying bulb in the streetlight. Cars were parked tight up against the white stucco buildings. We lived on a narrow street where no one knew our name, in a home that was meant to remain anonymous. But in the doorway—our doorway—there was a strange figure, standing and waiting.

A young woman, blond hair peeking from beneath her knit hat, wearing a plush parka, bent over her phone, her face illuminated in an eerie glow. Hearing my footsteps, she suddenly looked up. “You’re Sofie, aren’t you?” she said. “Sofie Morse?”

She held out a business card and I glanced down. I recognized her name. My heart began thudding against my rib cage. With a patient smile, she explained how much effort it had taken for her to track me down, given that I hadn’t returned any of her emails or phone calls, and she didn’t mean to startle me but she really did have some important questions to ask.

I took the card from her and looked away, mumbling, “Right, right, thanks. Uh, sorry, got to get these groceries inside.” I could sense her continuing to stare at me. She stood in front of the door, blocking the way. “Sorry,” I repeated. “Do you mind?”

As she stepped aside, she placed her hand on my arm and said: “So you’ll call me?”

Though I had no intention of seeing this woman again, I needed to get away from her. I nodded, and said I’d call her, because every second we stood here was another second in which she might see through me.

Upstairs, I unlocked our apartment door with shaking hands. I dropped the grocery bags to the floor, forgetting the carton of eggs, which now seeped from their cracked shells. I took deep breaths, trying not to panic. Stop freaking out, I told myself. You’re okay.

Except that a stranger had tracked me down, flown across the Atlantic, and waited on my doorstep for who-knew-how-long in the cold January night, because that’s how badly she wanted to know the truth; the truth, which, if revealed, could cause the entire operation to collapse. It wasn’t just my safety, or Ben’s safety. I’d been reminded, time and again, that the stakes were much bigger than that. No, I wasn’t okay. I was definitely not okay.

“It’s unlikely that you’ll need it,” the man had said, last year, back in New York. He had the seen-it-all sangfroid of a person familiar with the furthest edges of life. “But if you’re in real trouble, and you need to signal for a meeting, here’s what you do.”

I hurried into the bedroom and took the red towel from the shelf in the closet. I grabbed a few stray items from the laundry hamper—a T-shirt, a sweatshirt—and soaked everything in the kitchen sink. The towel was brand-new, never washed before. The red dye bled and stained the water. The wet bundle left a trail along the floor as I carried it to our small balcony, where we kept a collapsible laundry rack. On the outermost edge, clearly visible to anyone passing, the red towel dripped and dripped.

When Ben got home an hour later, his eyes were wide. He had seen the towel. Silently, he nodded toward the balcony. Why the towel? What happened?

I slid the business card across the counter. His eyebrows arched in recognition. The woman was a journalist from a TV network back in New York. She told me she would love the chance to talk about my relationship with Lara Caine, the First Lady of the United States. Would love, that’s how she phrased it. Would sell a kidney for is a better way to put it.

That night I lay wide awake, unable to sleep. The fear had ebbed and flowed since we arrived in Croatia four months before, but this was the worst yet. Ben breathed steadily in the darkness. Okay, I thought, engaging in my usual practice. Ask yourself this. What was I scared of? Was I scared of her? I was familiar with the hunger she felt, the relentless drive to uncover the truth. Wasn’t she just a journalist, not so different from me? Anyway, it wasn’t like she was interested in me specifically. She was only doing her job. As the gray light of dawn softened the edges of the bedroom curtains, I convinced myself that I had overreacted.

“What are you doing?” Ben said drowsily, as I climbed out of bed.

“Nothing,” I said. “Go back to sleep.”

No harm, I thought, bringing the laundry back inside. It had been an unusually cold night, and the towel had frozen stiff. Maybe no one had seen it and I would be spared from embarrassment. I ran a hot shower. I got dressed, brushed my teeth, and put away last night’s dishes. You’re fine, Sofie. I would live my life like it was any ordinary day, because that’s what I wanted it to be.

And I began every day with a long walk through town and along the corniche, where the towering procession of palm trees shivered in the wind. Or, more accurately, shivered in the bora: the name of the winter wind that swept along the undulating Adriatic coastline. Ben had defined the word bora for me. He read constantly, to keep his mind busy. He’d recently read Ernest Shackleton’s memoir, which inspired his suggestion that we each establish our own daily routines to maintain our sanity during this strange exile.

We’d arrived in Split the previous September. I thought we’d be in Croatia for a month, two months tops. We’d left behind our life in New York in a hurry, figuring we’d be back soon enough. Then two months turned into three, and then it was Christmas, and then it was a new year, and still there was no end in sight. Whenever I expressed guilt about the mess I’d gotten us into, Ben shook his head.

“Stop,” he’d say. “We did this together, Sofe.”

Except that my decisions—mine, not his—had brought us to this point. And no matter how many times Ben told me that it was okay, I couldn’t quite bring myself to believe him.

That morning, walking along the corniche, as the cold wind whipped my hair into a frenzy, I scanned the faces of everyone I passed. I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for—a returned gaze? surreptitious sign language?—but whatever it was, it didn’t materialize.

“We’ll have people on the ground,” the man had said to us, before we left. “They’ll be watching, just in case.”

I remembered nodding. I remembered feeling relieved by his reassurances. I remembered thinking: This man is a stranger, and yet we’re trusting him with our lives.

The bell on the café door jangled, and the waiters waved at me as I headed to my regular table. I liked this place. The café was too haphazard to be elegant, but it was cozy and generously heated in the wintertime. The room was tall and narrow, like a shoebox stood on its end. The tables were covered in red damask, with squares of white paper to shield the fabric, and the warm light of the sconces were reflected in the wall-hung mirrors.

They made a decent cappuccino, and the pastries were passable, but mostly I liked this café because the waitstaff remembered me, and that kindness made a tiny dent in our anonymity. The waiters—teenagers for the most part—were as bored and affable as high school students sitting through last period. The café was cramped, so they were constantly colliding with one another, spilling coffee and yelping in indignation, but they also never had quite enough work to keep themselves busy, and they bickered to pass the time.

My waiter that day, Mirko, was my favorite. He was gangly and gregarious, and saving money toward the goal of achieving his greatest desire, which was to travel to America—specifically to Chicago. (He was obsessed with Michael Jordan and could recite the entire roster of the 1996 Bulls.) That morning, as he placed my cappuccino and cornet pastry on the table—I hadn’t even needed to order it—Mirko said, “There is a big story about your president.”

“Oh?” I said. Even though a lot of Americans had long since wearied of the conversation, the foreigners I’d met remained intensely curious about President Caine.

“Yes,” Mirko said, standing up straight, looking slightly indignant. “It is very bad news. He says he is planning to visit Serbia next month for an important meeting.”

“Why is that bad news?” I asked.

“Bad for Croatia!” he exclaimed. “We are much more beautiful than Serbia. Why would he go there instead of here? He is choosing our greatest rival instead of choosing us, even though we are so much better. It is very bad.” Mirko’s eyes were wide. “Why do you think he did this, Sofie?”

“Who knows?” I said. “No one understands him, Mirko.”

After Mirko left, I scrolled through the news on my phone, just like every morning. I glanced up whenever the bell on the door jangled— a pair of tourists chattering in German; a mother with a baby swaddled against her chest—but none of the new arrivals met my eye. There was a story that day about Caine’s recent phone call with Russian president Nikolai Gruzdev. The White House released little detail about the conversation, except to emphasize that Gruzdev was fully supportive of Caine’s recent decision to withdraw American troops from Mozambique.

“Great conversation with President Gruzdev, or as I call him, NICKY!” Caine tweeted. “We are making progress!”

I kept scrolling, but stopped abruptly when I saw a story about the construction of Nord Stream 2. Nord Stream 2 was Russia’s new natural gas pipeline, which would begin at the country’s western edge, snake through the Baltic Sea, and end in Germany. Officially, America was opposed to the pipeline for geopolitical reasons. Unofficially, President Gruzdev knew that his American friend Henry Caine wouldn’t do anything about it. The article described how worried the state department and foreign policy wonks in Washington were about the rapid progress of the pipeline. But no amount of saber rattling could change reality, which was that Caine wasn’t going to stand in Nicky’s way.

For a long time now, the world had suspected there was an understanding between the American president and the Russian president. Almost two years earlier, at the conclusion of a lengthy investigation, the Special Counsel released his report, which contained certain clear facts. Yes, the Russians used disinformation and propaganda to help Caine win his first election. Yes, Caine treated Gruzdev with special favoritism once elected. Yes, there was an increasingly worrisome pattern of their agendas aligning. But there was no smoking gun. No secretive backroom deal. If there was something distasteful, something ugly, about the relationship—well, Caine never let himself become troubled by mere ugliness.

My coffee and pastry long since finished, I was standing up and leaving a tip for Mirko when I noticed a gray-haired woman across the room. She stood at the bar, talking with the waiter. Another regular, it seemed. (But why had I never seen her before?) She turned away from the bar, carrying a brimming cup of coffee, but kept looking back at the waiter. As she walked blindly across the room, right toward me, the collision seemed to happen in slow motion. Scalding coffee, up and down my sweater.

“Oh my God! Oh my God, I am so sorry!” she exclaimed. She launched into a multilingual apology: “Je suis désolée! Mi scusi! Es tut mir Leid!”

I shook my head. “It’s fine,” I said, reaching for a napkin.

“No, no, I am so embarrassed. Please let me help you.” She seized the napkin and began dabbing. “Oh, your poor sweater. I ruined it. I am so sorry. Here, please. Come with me. I’ll help you.”

She grabbed my hand and, before I could object, dragged me toward the bathroom. She ran the faucet, and then turned around to lock the door.

“Well, Sofie,” she said in a brusque tone. “I’m sorry about the sweater, but it was the only way.”

I swallowed hard, performing rapid calculations. “You’re…? So you saw…?”

“My name is Greta,” she said. In the claustrophobic bathroom, with the harsh light and the scent of chemical cleaner, this woman had undergone a chameleon-like transformation. Her mouth set in a grim line, her eyes hard and unblinking, she looked nothing like the carefree woman of a few minutes ago. “I am a friend of your friend. Are you and Ben okay? You have something you need to tell us?”

I felt vaguely terrified of Greta, and inclined to do whatever she told me. But as I was starting to sputter out an explanation, it came back to me: another instruction from that distant day.

“No, wait. Wait a second,” I said, shaking my head. “How is… How is my neighbor Maurice doing?”

She gave a brisk nod. “The soil is healthy. The tulips will have a good spring.”

“Okay,” I said, mirroring her movement, nodding to myself. Okay.

I described what had happened the night before, how the producer, who had been calling and emailing for weeks, had actually shown up in person. “On my doorstep,” I said, my voice straining. Saying it out loud made me understand just how real it was. “Where we live. Where we’re supposed to be safe.”

“Yes,” she said. “I thought it might be that. We saw her, too.”

“Then you need to help me!” I exclaimed. “Get her to leave me alone.”

“No, Sofie. Think about how it would look if we interfered.”

“I don’t care how it looks!” I said, the heat rising in my cheeks.

“Certainly you care.” Her tone was cold, as if the concept of caring was mere abstraction. “Think, Sofie. Why would she come all the way to Croatia? She suspects something. Likely, that you haven’t told the full truth about your relationship with Lara Caine. You’re a journalist. If someone tried to stop you, what would it make you do?” She stared at me bloodlessly. “You’d just work ten times harder, wouldn’t you?”

A knock on the bathroom door.

“One minute!” Greta shouted. Then she continued: “Here’s what we want you to do. Take the meeting. Show her that you have nothing to hide. You might even learn something useful in the process. The nature of her suspicions. The reason for her persistence. Really.” She arched an eyebrow. “You have nothing to fear from her. She’s exactly who she says she is. She’s just looking for a good story.”

“I can’t do it,” I insisted. “I’m not a good enough liar.”

“She wants a good story,” Greta repeated, like a teacher instructing a slow-witted student. “Isn’t this the nature of your work? Certainly you have experience coming up with a good story.”

She grabbed a handful of paper towels and held them out to me. “Here,” she said. “You ought to clean yourself up before you go back outside.”

As I walked home through the cobblestoned streets, I pulled out my phone. Maurice was our upstairs neighbor in New York. It gave a pretext for my regular calls: he was checking our mail, watering the plants, keeping an eye on things. His landline rang, and there was his familiar voice, his Russian accent still strong even after decades in America: “Good morning, Sonechka.”

“How did you know it was me?”

“You’re the only person who calls this early,” he said. It would be dawn in New York, darkness out the window. Maurice was an early riser, brewing tea to the soft strains of Mozart on WQXR while the rest of the building slept. “But I’m glad you did. I have some news.”

“News?” I said, pricking to attention.

“I spoke to our friend yesterday,” he said. “Our friend was in good spirits.”

“That’s good,” I said, my heart suddenly thumping. “Isn’t it?”

“I said you were very happy with your new routine.”

“Oh,” I said. “Uh, yeah. Of course we’re happy. But there was nothing about”—I searched for the right words, the right disguise for the question I was asking—“about, you know. How the work is going?”

“I’m sorry, Sonechka,” he said. “We spoke for only a minute or two.”

“Ah,” I said. (Why did I bother? Why did I search for reassurance when I knew, I knew, there was none to be found?) “Okay. Well, the reason I called is that, actually, something weird happened last night.”

“Oh?”

“This TV producer from New York,” I said. “She wants to interview me for a feature about Lara Caine. She showed up on my doorstep. I don’t know how she found me.”

“Interesting,” Maurice said quietly. “Do you think you’ll say yes?”

“I think”—I coughed, my mouth gone dry—“I think I have to.”

A brief silence on the other end. I could picture it so vividly: Maurice walking to the window, pulling back the curtain, checking to see if anyone else on the block was awake. Keeping an eye on things, like always. I heard the clink of his china cup in its saucer.

“Yes, that sounds sensible. Curiosity is to be expected,” he said. “What you had with Lara Caine was very unusual. Of course this person wants to know more.”

Looking back, it’s strange to think how quickly everything happened. Lara Caine was the third wife of President Caine, the only First Lady since Louisa Adams to be born outside the United States, the most enigmatic occupant of the East Wing in decades, the silent companion of the most toxic leader in American history, the couture-clad Rorschach test for the nation at large—and the subject of my next book.

That was the plan, at least. After her husband was, horrifyingly, reelected to a second term, Mrs. Caine had approached me to write her biography. The access she granted was irresistible, giving me free rein with memories, diaries, photographs, and family members. She had no desire to write her own book. Like any wealthy woman, Mrs. Caine was comfortable with delegation: she relied on professionals to cook her meals, style her hair, tailor her clothes. So why not have a professional tell her story? The First Lady demanded no control over the final product. As far as I could tell, there were no strings attached.

I hesitated at first. I wondered whether it was selling out; whether devoting so much time to this project would be amoral, or immoral. Wasn’t it cynical to say yes? But Lara Caine had made it impossible for the public to get to know her. Like the rest of America, I’d assumed things about her without really knowing anything about her. So was it cynical to say no? I spun in circles for a while, but in the end, my curiosity decided for me.

And her life, I soon discovered, had been unusual and eventful. The material was rich. Mrs. Caine and I settled into a comfortable routine. Trust blossomed. We grew closer. I expected the arrangement to last awhile. There would be a lot to cover.

Before we began, I hadn’t been planning on doing anything like this. I’d written a book years earlier, but that was an accident more than anything else; after graduate school in England, I was able to turn my history dissertation into a book that sold modestly but respectably. After that, at the tail end of my twenties, I’d moved to New York. I began working as a journalist just as the brash oil tycoon Henry Caine was casting his eye toward Washington, DC.

Calling myself a journalist was charitable, at first. I had no training in cultivating sources, or digging up scoops, or writing on deadline. But I could reach into the past and unwind dusty skeins of context for readers, and my new boss, the managing editor of the newspaper, thought that was useful for the times we were living in. The day after Caine won his first election, she reassigned me to the White House beat.

“We need someone like you in that chair right now,” Vicky said. “And you wanted to learn, right? Well, you’re going to learn a lot on the fly.”

The newspaper was a lean operation, a few steps above the local city tabloids but nowhere near the New York Times and Wall Street Journals of the world. It was mostly propped up by analog subscribers who were too loyal or apathetic to cut bait, and while it had no national presence to speak of, it had been chronicling Henry Caine, a born-and-bred New Yorker, for decades. These were stories that the wider world suddenly cared about, and it led to a resurgence of readership, and profit. For the first time in years, the budget steadied. For those of us at the newspaper, it was nice to get a raise and a 401(k) match, but it was also unsettling to realize the source of this newfound prosperity.

Four years, which seemed like a life sentence at the outset, went by quickly. Despite his constant sabotage, both of himself and of the country, Caine had enjoyed an unbroken streak of luck. The corruption investigations resulted in a collective shrug; the impeachment proceedings failed to pass; and the economy remained white-hot, which apparently was all that mattered, because there we were, gathered in the newsroom on a Tuesday night in November, a little after 9:00 p.m., and the networks had just called Pennsylvania for President Caine.

Vicky Wethers crossed her arms as she stared at the TV. The electoral map disappeared from the screen, replaced by a panel of pundits, arguing about what to expect from his second term. Vicky said to no one in particular: “Well, of course. Who’s going to vote against three percent unemployment?”

“Someone with a conscience,” Eli chimed in. “Someone who gives a rat’s ass about more than their bank account.” Eli was old-school, coming up during the New York tabloid wars. He had the habit of cracking open hundreds of pistachios a day, which he started doing after he quit smoking because he had to do something with his hands.

Vicky sighed. “This is so depressing.”

“It’s like he’s made out of Teflon,” I said. “The normal rules just don’t apply to him.”

Eli craned his neck toward me, popping in a handful of pistachios. “When’d you get to be so jaded, Morse? Nah, the rules apply to everyone. Sometimes they just take longer to catch up.”

“How long is longer?” I said. “At this rate, he’ll be dead before they catch up to him.”

He shook his head. “Eventually something’s gonna stick. I’ve got this guy at Langley, he’s convinced there’s something weird about that Dresden meeting.”

“Dresden?” I echoed, half listening while texting with a White House source (on background, she said, most of them were miserable that night; his aides wanted nothing more than for Caine to lose, and for their lives to get back to normal). I didn’t give much attention to what Eli was saying. Eli had a lot of guys, and those guys tended to have a lot of theories.

“Yeah. That summit he had with Gruzdev, a few years back? Where the two of them snuck off and Caine wouldn’t let anyone else inside the room? Not even our side’s translator? My guy thinks that—”

“Hold up,” Vicky said, waving at Eli to be quiet. “We’re getting something out of Ohio.”

In unison, we swiveled toward the TV screen. Nights like this were when the office was most alive. Some moments in history arrive quietly. In graduate school, we talked about the hidden turning points, which are only revealed with plenty of retrospect. Who could imagine the ripple effects of these contingencies—the heir born with hemophilia; the Austrian boy rejected from art school; the invisible mutation of a spike protein structure? But other moments in history arrive like a screaming meteorite. You can’t help but know that you’re living through something. When that happened, we sprang into action.

That night, while Vicky paced the floor and asked for updates, I thought about Ben and our group of friends. They would be watching the returns at someone’s apartment on the Upper West Side, frantically changing channels, sifting for nuggets of hope as the night unfolded. I could imagine the empty bottles of wine on the sideboard, the remnants of cheese rind drying out, the shattered fragments of tortilla chip at the bottom of the bowl. I was glad not to be there; I was glad, at least, to have this task to keep myself busy. And yet that gladness left a sour taste in my mouth. It was an awful, ironic privilege of this job—to always be distracted, to always have more work to do. Chronicling the nonstop drama had created a strange set of blinders, numbing me to the pain. I hated that I felt this way. Four years of this had left their mark. What, I asked myself, will another four years do?

Vicky stepped behind me, leaning forward to look at my screen. “How’s it coming?”

“Almost done,” I said. “It’ll be ready to go as soon as the networks call it.”

Vicky once said it was my job to tell readers how bad it really was. Taking the long view, and considering everything we’ve been through before, tell us: Are we at DEFCON 3, or DEFCON 2, or, God forbid, DEFCON 1? I told her it wasn’t possible for any one person to know such a thing, and certainly not within the moment itself.

She said, “I’m not asking for perfect empiricism, honey. I’m asking for a smart person’s educated guess.”

It had taken me a while to really understand her request, and figure out how to answer it. Vicky wanted an assessment that wasn’t drawn solely from the brain. On a night like this, the screaming meteorite provoked a specific kind of physiological response: the adrenaline, the rapid heartbeat, the deepened breathing. Sometimes history announces itself within the bloodstream.

HENRY PHILIP CAINE, MORE THAN ANY CHIEF EXECUTIVE IN AMERICAN HISTORY, SPENT HIS FIRST TERM MIRED IN UNPRECEDENTED SCANDAL. AFTER DEVASTATING INVESTIGATIONS, REPEATED CALLS FOR HIS IMPEACHMENT, AND HISTORICALLY LOW APPROVAL RATINGS, PRESIDENT CAINE APPEARED TO BE A FATALLY WOUNDED CANDIDATE. BUT ON TUESDAY, AMERICA CHOSE TO RETURN HIM TO THE WHITE HOUSE FOR ANOTHER FOUR YEARS.

The next morning, I walked to a coffee shop on Eighth Avenue, a popular spot around the corner from the office. The sleek white walls and black cement floors were a trendy picture of elegant restraint. There were only a few drinks on the menu (cappuccino, latte, drip coffee), and even fewer pastries available within the small glass case. Fewer options meant fewer chances to choose the wrong thing, and lately people seemed to crave that certainty.

A long line of customers snaked through the front door into the November sunshine, smartly employed men and women within that substantial bracket of thirty- to fiftysomethings who had enough money to splurge on high-end coffee but not enough power to send an assistant to get it for them. As the line crept forward, people were mostly staring at their phones, insulated by white earbuds. Despite the morning rush, the tables inside were nearly empty. Except for a table in the back, where Vicky sat, two coffees already procured.

“I thought I was on time for once,” I said, unzipping my coat, which was too heavy for the mild weather. My neck was sticky, and sweat pricked my forehead. I felt vaguely, irrationally annoyed with myself. This was an important moment, and I felt like I was botching it.

“You are on time,” Vicky said, removing her reading glasses and setting aside her phone. “But you know me. Always early. My congenital defect. Did you manage to sleep?”

“A little. Poorly. Did you?” I said, as she handed me the coffee.

“Four hours, like a rock.” Vicky smiled. She somehow looked the same every single day, regardless of sleep or weather or season. Neatly cut gray hair, colorful blazer, her blue eyes radiating tiny deltas of wrinkles. “So this is it, huh? I’m guessing that if you’d changed your mind, you wouldn’t be looking so forlorn right now.”

I smiled weakly. “Do I really look that bad?”

“Well, you look ready for a change.”

“Vicky, I wanted to say thank you.” A lump was swelling in my throat. “For everything. I’m going to miss you. I’m going to miss this. And I wish I could keep going, but I just—”

“Oh, Sofie,” she said, waving a hand. “Sweetheart. Don’t say another word.”

Quitting had been contingent on the election. If Caine lost, I’d stick it out for at least a few more months and cover the transition, and then decide. But Caine winning only meant more of the same: more stress, more sleepless nights, more exhaustion. Other people, like Vicky, seemed to stay centered in the chaos. But I hadn’t figured out how to do that.

Vicky understood. And life was long, she said; maybe I’d come back someday. In the office, it took me only an hour to pack up my desk. I said my goodbyes, handed out my personal email, promised to keep in touch. As I stood at the elevator, pressing the Down button and surveying the newsroom one last time, Eli appeared, carrying a cup of coffee from the kitchen. “Jesus, Morse,” he said, eyes widening. “I almost forgot. You’re really quitting?”

“Don’t miss me too much,” I said, with a tremor of slightly false cheer.

“But you’ll be back,” he said, wrapping me in a bone-crushing hug. “I know you will.”

Many months after that, when I was in the thick of working on the First Lady’s biography—at times feeling almost cocky at how everything had worked out—I had lunch with Vicky at her favorite spot in Midtown. She said, “Level with me, Sofie. This whole Lara Caine thing. Did you always know this would be your exit ramp?”

In that moment, I was tempted to say yes. Fudge the timeline a little, make the narrative work in my favor. Sure, of course, this had been my plan all along.

But it wasn’t even the tiniest bit true, and the lie never felt worth it. Lara Caine had a meticulous memory. She hated half-truths and untruths muddying up the public record. If rumor reached her that her biographer was claiming to be the mastermind—well. A mistake like that would just make both of us look stupid.

The biography was entirely her idea. We were clear on that. Later, the sharpness of this delineation proved exculpatory: it was a relief, more than anything, to let her take the credit, to back away from what it had wrought. The same words, the same truth, took on a new valence: It wasn’t my idea, said quietly with shrugged deflection, became It wasn’t my idea!, shouted in defiance.

On that day in November, as I left the office with my box and tote bags, I did have vague ideas of writing another book—that much was true. Ben and I had repeatedly calculated how to pull this off. Our rent was this much. Ben’s law school debt was that much. His twice-monthly paychecks, my twice-yearly royalty statements from a book that continued to sell modestly, and a small mutual fund that could be liquidated if needed. All of this could keep us going for a while, as long as we kept our costs low.

After that last morning at the office, I came out of the subway at Sixty-Eighth and Lexington, emerging into a scrum of Hunter College students who were perched on stone ledges, shrieking energetically on their lunch break. The halal cart on the corner was doing brisk business, sending up savory billows of smoke and the mouthwatering scent of lamb gyro. The intersection had an almost summery mood. Virtually no one in New York City was happy about last night’s results, and yet life was carrying on, in the usual way.

I walked north on Lex and turned down Seventy-First Street, where Ben and I had lived for the past five years. We’d met on a dating app when I was thirty and Ben was thirty-one. Love was instant, borne both of chemistry and sheer relief. Neither of us felt like wasting time. Three months after our first date, we moved in together. Six months after that, we got married. Most people assumed the accelerated timeline was because we wanted a baby, or that one was already en route. They never imagined the opposite to be true: that part of our certainty sprung from a shared lack of that desire. Our apartment on East Seventy-First Street was charming and tiny. “Just right for two,” the broker said, when she showed us the space, five years earlier. She had given me a meaningful look, one that lingered on my midsection, one that any woman in her thirties quickly learns to decipher.

I loved our little apartment. We lived in the garden level of a narrow town house. The house had been divided into four apartments, one on each floor, and if you were lucky enough to land in one of them, you tended to stick. That day, in the small front courtyard outside the building, our neighbor Maurice Adler was watering his trough of bright yellow goldenrod and his hardy witch hazel shrub. Maurice was an elegant man, probably in his seventies, though I was never sure of his exact age. He was originally from Saint Petersburg (“Peter,” as he always called it), and had lived in the parlor level of the town house since moving to New York in the 1990s. He knew everything and everyone in the neighborhood. He liked to stroll around the block on summer evenings, and to linger at the coffee shop on Lexington. The moment he moved here, he said, he knew that his years of wandering were finished for good.

“Sonechka,” he said. The arcing spray from the hose caught in the sunlight, glittering like a chandelier. “Was today the day?”

“It was,” I said, stepping down into the courtyard, which wasn’t much bigger than a parking space and just deep enough for a few stone planters. “And I survived.”

“Bravo,” he said. “I had a good feeling about it. The sunshine is an omen.”

The faucet squeaked in rusty protest as Maurice bent to turn off the water. He’d retired a few years ago but still dressed as he did when he was a professor at Hunter. Pleated khakis, checked Turnbull & Asser shirt, softened penny loafers, trimmed gray mustache. As he wound the garden hose into a neat coil, he said, “Are you hungry? I was just about to have some lunch.”

I followed Maurice through the main door, to the right. Because Ben and I lived on the garden level, we used the old service entrance over to the left. This was one of my favorite details of the apartment. To live in Manhattan, and to have a proper front door? During our first winter in the apartment, when I bought an overpriced wreath from the Christmas tree stand on Third Avenue and hung it on that door, I felt anchored in a way that I hadn’t felt in years.

Maurice opened his door and ushered me into his bright, high-ceilinged living room. When he instructed me to sit, I sat, because I knew better than to offer my help in the kitchen. Even for a spur-of-the-moment lunch, Maurice took hosting seriously.

Several minutes later, he carried in a tray with two steaming bowls of chicken soup, shimmering gold studded with fragrant dill. On the side were slices of dark rye bread and a pot of sour cream. Maurice was a good cook, although his repertoire was mostly limited to the food that reminded him of home. When he was in the mood for French or Italian, he said, he would rather it be cooked by someone who knew what they were doing.

“I read your story in the paper this morning,” he said, spreading sour cream on his rye bread. “I liked it. It was quite good.”

I smiled. From Maurice, “quite good” was the highest compliment you could hope for.

“Thank you,” I said. “It’s funny, it felt hard to get that one right. Even though everyone knew Caine was going to win.”

Maurice nodded. “There’s a difference between knowing a thing and articulating a thing.”

“And a difference between articulating a thing and understanding a thing.” I blew on a spoonful of soup, waiting for it to cool. “Which, I think, we’re a long way from. No one knows what to do with a man like Henry Caine.”

Maurice frowned. “If only that were true.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I fear that some people know what to do with him.”

Before I could ask him to elaborate (Some people? Was he thinking of anyone specific?), we were interrupted by a shrill ring.

“Pardon me, Sonechka,” he said, standing to answer the phone. “My doctor is supposed to call about a prescription.”

Maurice spoke quietly for a few minutes, occasionally saying, “Could you repeat that, Doctor?” while he took notes on a pad on a small end table. The rotary telephone, like Maurice, was old-fashioned and worked perfectly well. Maurice’s health was sturdy, his mind sharp, his energy unflagging. He was one of those people who managed to locate the fountain of youth in the New York City water supply.

Once, in the early days of our friendship, I’d asked him if he would ever go home.

“To Russia?” he said. “No, never. There’s nothing for me in Russia.” A funny answer, it seemed, for a man whose apartment was bursting with nostalgic reminders of that past life. The old samovar on the sideboard; the sepia photographs of long-departed family members; even the too-warm temperature of the air and the lingering smell of woodsmoke spoke of his traditional Russian fear of the cold (from October to April, Maurice lit a fire in the fireplace every night, no matter how mild the weather).

“Did I tell you that I have a new internist?” Maurice said, as he returned to the brocade sofa. “She is very young. Younger than you, I think.”

“What happened to Dr. Feltner?”

Maurice drew his hand across his throat and then shrugged grimly.

I burst out laughing. “Sorry,” I said. “That isn’t funny.”

“Well, it comes for all of us, doesn’t it? So tell me. You’re still planning to write another book? Have you decided on a subject?”

I shook my head. “Not yet. I guess I could write about Caine. The gold rush is still going, you know? Those books do really well.”

“Yes, the appetite is endless,” he said. “But do you want to keep writing about him?”

“No. Not really. Actually, I want to get as far away from that as possible.”

“It doesn’t interest you anymore?”

“I just don’t think my writing about it—I mean writing about him, that whole world—will do anyone any good.” I paused, hesitating, but if Maurice wouldn’t understand these things, who would? I said, “Is it stupid to say that whatever I do next, I want it to… I don’t know, I want it to mean something?”

“My dear,” he said, “that is the opposite of stupid.”

We were quiet for a while, concentrating on our food. The old brass carriage clock on the mantelpiece ticked sedately. Maurice must have sensed what I was wrestling with, because he prompted: “Tell me again, Sofie, how you came to write your last book.”

“It’s not a very interesting story,” I said. “My tutor at Oxford, he thought Raisa Gorbacheva was never correctly assessed or understood, from a historical perspective. It bothered him that Westerners didn’t really know who she was. So that’s what I wound up writing about. Anyways, that’s my problem! It wasn’t my idea.”

“But you’re the one who actually wrote it,” Maurice said. “What I’m wondering is, why did you pursue that idea?”

“I was curious about her, I guess.”

“Well, then, that’s all you have to do.” He sat back on the couch, crossing one leg over the other. “Just follow that curiosity, Sonechka. It will lead you in the right direction. And then you will write a wonderful book.”

This was signature Maurice: he made it sound so simple. He’d adopted certain American habits over the decades—rooting for the Yankees, a weakness for Snickers—but he remained a Russian fatalist to his core. Things would unfold that way because they had to unfold that way. I wanted to believe him. But I also knew that wasn’t how the world worked.

Maurice Adler, my upstairs neighbor. What can I tell you about him? He was born in Leningrad in the wake of the Great Patriotic War. He was a brilliant and promising student. In the 1960s, he enrolled at the newly opened Novosibirsk State University to study physics, but he came to loathe the violent application of that science in a nuclear-obsessed Cold War world. He wanted to switch disciplines and study philosophy instead, but the Soviet Union in the era of general secretary Leonid Brezhnev was not a place in which personal opinion mattered very much. So Maurice left. He went to Heidelberg for a new course of study and patched together an itinerant career from temporary teaching positions across Europe. Finally, he came to America in 1991, settling into a post at Hunter College, where, for over twenty-five years, he was busy, productive, and beloved. When he retired, Hunter students past and present crowded into the back room of a nearby restaurant to toast him.

What else could I tell you about Maurice? The names of his doctors, and how he took his coffee at the coffee shop on Lexington, and what time he went grocery shopping. His smile when talking about a book he loved. The way he arched one eyebrow and leaned back slightly while preparing to engage himself in argument. The creaking sound of his footsteps across his living room floorboards, announcing his retreat to bed every night at ten. His unfailingly direct way of speaking.

It was easy to trust in the wisdom of everything he said. But he had lived an entire lifetime before ever setting foot in New York City, and I only ever knew the broadest strokes about his past. Well, what did that matter? He didn’t seem inclined to dwell on it. I never suspected what he was leaving out.

I thought it would come as a relief, having these acres of unbounded time, this chance for leisurely lunches and afternoon naps and unread novels. But that first week after leaving the newspaper, I only felt restless. I walked around the apartment, picking things up and putting them down, my attention span in tatters. Four years of President Caine had done something bad to my brain. I had to relearn how to live in the real world.

There was a diner around the corner from our apartment, with counter seating and vinyl booths and faded posters of Greek islands behind the cash register. That first week of freedom, I went for an omelet during the lull between breakfast and lunch, sitting in a booth and staring at the pages of a novel while the waiter refilled my coffee. I couldn’t concentrate, but passing time felt like a more meaningful act when performed in public.

A woman slid into the next booth over. “Coffee, please,” she said to the waiter. “And a blueberry muffin, toasted with butter.” She pushed her black sunglasses into her blond hair and squinted at her phone. Cashmere cardigan, Chanel flats, Goyard tote bag. Midthirties, around my age. She was a neighborhood type, but which? Mother of young children? Overworked professional? Both, it became clear, as she answered her buzzing phone.

“Tell them I need to call in to the eleven thirty,” she said. “Theo has some kind of stomach bug. That preschool is a hot zone. Anyway, listen, I looked at the board deck. The third slide is all wrong. You have to—”

Could I help feeling a slight envy? That life wasn’t the life I wanted, but still—that woman was so busy, so certain, so needed. I was having trouble breaking the habit of constantly looking at my phone, so I’d left it at the apartment when I went to the diner, hoping an hour of forced separation might help. It was mostly silent these days, anyway.

But when I got home, there was a missed call, and a voice mail.

“Sofie,” the vaguely familiar voice on the message said. “This is Gabi Carvalho, the First Lady’s chief of staff. We met a few years ago, as you probably remember. Could you call me back as soon as you get this? It’s important.”

Reading Group Guide

Introduction

Tired of covering the grating dysfunction of Washington and the increasingly outrageous antics of President Henry Caine, White House correspondent Sofie Morse quits her job and plans to leave politics behind. But when she gets a call from the office of First Lady Lara Caine, asking Sofie to come in for a private meeting[HK1] , her curiosity is piqued. Sofie, like the rest of the world, knows little about Lara—only that she was born in Soviet Russia, raised in Paris, and worked as a model before moving to America and marrying the notoriously brash future president.

When Lara asks Sofie to write her official biography, and to finally fill in the gaps of her history, Sofie’s intrigued. She begins to spend more and more time in the White House, slowly developing a bond with Lara—and eventually a deep and surprising friendship with her.

Even more surprising to Sofie is the fact that Lara is entirely candid about her mysterious past. The First Lady doesn’t hesitate to speak about her beloved father’s work as an undercover KGB officer in Paris—and how he wasn’t the only person in her family working undercover during the Cold War.

As Lara’s story unfolds, Sofie can’t help but wonder why Lara is rehashing such sensitive information. Why to her? And why now? Suddenly Sofie is in the middle of a game of cat and mouse that could have explosive ramifications.

For fans of The Secrets We Kept and American Wife, Our American Friend is a propulsive Cold War–era spy thriller crossed with a fictional biography of a First Lady. Spanning from the 1970s to the present day, traveling from Moscow and Paris to DC and New York, Anna Pitoniak’s novel is a gripping page-turner—and a devastating love story—about power and complicity and how sometimes, the fate of the world is in the hands of the people you’d never expect.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Consider the epigraph from Arthur Koestler (page vii). How does this passage set the tone of the novel? Who do you think is the “one” referenced in the quote? How is reading similar to thinking “through other people’s minds”?

2. In the opening chapter Sofie encounters Greta, who tells her to fend off a snooping journalist by feeding her a story, saying “She’s just looking for a good story. . . . Isn’t this the nature of your work?” (page 8). What do you consider the nature of Sofie’s work? How did Sofie’s perception of her work, or her purpose, change during the course of the novel?

3. “Lara Caine had made it impossible for the public to get to know her. Like the rest of America, I’d assumed things about her without really knowing anything about her” (page 10). Does Lara Caine remind you of any real individuals in the celebrity or political sphere? Do you think the American public deserves to know the life stories of the people in the White House? Are public figures obligated to share details of their personal lives and histories?

4. At its heart, Our American Friend centers on an unexpected relationship between two women. Would you call the connection between Sofie and Lara a friendship? What are the moments when their relationship seems to change? How do you define what makes a friendship?

5. Following Henry Caine’s second election win, Maurice and Sofie discuss the variable differences between knowing a fact, articulating a fact, and actually understanding a fact. Have you ever had a moment in your life where you’ve struggled to put something you know into words? Are there other examples in the novel where this consideration for knowing versus articulating versus understanding could be applied?

6. Early in the novel Sofie thinks to herself: “Some moments in history arrive quietly. In graduate school, we talked about the hidden turning points, which are only revealed with plenty of retrospect. Who could imagine the ripple effects of these contingencies—the heir born with hemophilia; the Austrian boy rejected from art school; the invisible mutation of a spike protein structure? But other moments in history arrive like a screaming meteorite. You can’t help but know that you’re living through something” (page 12). Have there been times in your life where you felt you were witnessing something of historical importance? Can you compare which instances felt obvious, and which arrived “quietly”?

7. Consider the novel’s structure. How did the multiple timelines and story-within-a-story contribute to your reading experience? Did you have a favorite perspective or period in Sofie or Lara’s stories?

8. The novel shares many ingredients with classic spy stories and Cold War novels from writers like John Le Carré, Graham Greene, and Alan Furst. Many of these stories center their plots on male protagonists and male spies. How is female voice and agency incorporated into Our American Friend?

9. Loyalty and trust are two themes that go hand in hand throughout the novel. Consider these themes in regards to Lara’s relationship with her family, especially her father. How do Lara’s loyalties evolve alongside her trust? Who and what is Sofie loyal to throughout the novel? Is there a difference between being loyal to an individual versus loyal to an ideology or state?

10. Describing Sasha’s point of view in 1980s Paris, Lara observes: “In a world full of murky unknowns, Sasha believed in certain incontrovertible facts. The KGB was always watching, women always wanted children, and so on. He could never quite let go of those bedrock assumptions” (page 14). What other “bedrock assumptions” are at play in the novel? What certainties do these characters cling to? And how do these certainties impact their decision making, for better or for worse?

11. Our American Friend is partially set in the 1980s, a period of open hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union (and their respective allies). How familiar were you with this period of history before reading the novel? Did you learn anything new? Did it challenge your opinion of the period or its ideologies?

12. Lara had specific reasons for choosing to tell her story through a biography rather than write her own memoir. Putting yourself in her shoes: Would you prefer to write your own memoir or share your life with a writer for a biography? If you could write the biography of someone—a celebrity, a historical figure, or even someone in your own life—who would it be and why?

13. Consider Lara’s age when she first met, fell in love with, and then lost Sasha. How do you think her actions would change if she were older, or at a different[HK2] point in her life? Discuss the arc of Lara’s motivations throughout the novel. What were the dramatic turning points which affected her actions?

14. Maxim, Lara’s grandfather, refers to her family’s life in Paris as “living with contradiction,” in that they “must hold two ideas in [their] head at the same time . . . love—as real as it feels—is not reality[HK3] , and it will never alter reality” (page 115). Are there other examples in the novel of characters living with contradiction? Do you believe Maxim’s statement that love is not reality? What are the instances where this is statement is illustrated, or challenged?

15. When Ben and Sofie decide to go live in Croatia, they are both making sacrifices that have immediate and long-term consequences. How would you feel if you needed to pick up and move your life to a totally new or foreign location? If you could choose one person to share that experience with, who would it be?

Enhance Your Book Club (3–5 Enhance Your Book Club Suggestions)

1. Find a recipe for the traditional Russian snack Irina makes Natasha and Lara as children, sirniki[HK4] , or cheese pancakes, and share with the group. Try a variety of savory and sweet toppings like jam, sour cream, cheese, or fresh fruit!

2. If you’re interested in experiencing more spy drama set during the Cold War, consider watching the films Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy or Bridge of Spies, or the TV shows The Americans or The Company.

3. Virtually visit Paris! Head to www.360cities.net and search for the Luxembourg Gardens, or use Google Maps to follow Sasha’s journey (found on page 140) from the offices of The Spark to the Île de la Cité and use street view to see the Notre Dame cathedral.

4. Check out one of Anna Pitoniak’s previous novels, Necessary People or The Futures. Learn more about both and author updates at www.annapitoniak.com.

A Conversation with Anna Pitoniak

Q: Congratulations on publishing Our American Friend! Can you tell us about the inspiration for the novel? Did you have any specific questions motivating your writing?

A: Thank you! The story evolved over time, but the first seed for this book was planted back in the spring of 2016 when I read a profile of Melania Trump. One detail really stuck with me: she grew up in Yugoslavia, in a Communist country where most people had very little money, but her family was well-off. Her father had a comfortable job, and he was a member of the Communist party.

I kept wondering what this would be like, to grow up with one culture and ideology, and eventually occupy the pinnacle of power in a very different kind of culture and ideology. What would that be like? Did her values change? Did her loyalties change? Had something happened to cause these changes?

I knew that I didn’t want to write about the real First Lady. I wanted to let my characters emerge from the imagination. So Lara Caine has a few things in common with the real First Lady, but she is also very much her own person.

Q: What kind of research did you do while writing? Were you very familiar with the Cold War era or spycraft before working on Our American Friend?

A: I was already curious about the Cold War and spycraft, which is probably what spurred me to write this story! But as I began the first draft, I realized how much I didn’t know. So I threw myself into research. I wanted to know the details of what it was like to be alive at that time, in 1980s Moscow and Paris, and what it was like to work as a spy for both Russia and for America. Most of my research came from reading, from dozens of books—biographies and memoirs and other nonfiction. But the coolest part of my research involved a visit the CIA headquarters down in Langley, and a weeklong trip to Russia. Those in-person experiences were hugely helpful.

Q: Do you think you could have made a good spy? Did you have any favorite spycraft details that stuck out to you?

A: I don’t know! Some of my novelist skills might have come in handy. Making up a cover story or identity might not be that different from writing a scene in the novel. But it takes so much courage to be a spy, to actually put your physical self on the line, to risk that danger. That isn’t easy. Spies have to be cool under pressure, and able to think on their feet. If they get trapped in a lie, they have to talk their way out of that trap.

I loved learning the details of how spies communicate with one another. They have to assume they’re being watched, which means everything happens in code. A spy might walk out of her house wearing a particular piece of clothing, or carrying a particular kind of bag, and that might communicate a very specific and urgent message to her handler. I loved that idea of secret messages hiding in plain sight.

Q: It’s difficult to categorize Our American Friend into one genre! Was it hard [HK5] to pull elements of historical fiction, spy novels, political thrillers, and romance together? Did you always know what the structure of the novel would be?

A: I didn’t set out to write a specific genre; my only goal was to tell the story of Lara and Sofie in a way that was exciting, vivid, and moving. It turned out that this meant pulling from all those different categories! I tried to let it unfold as organically as possible. At the beginning of the writing process, I played around with a few approaches, but quickly realized that, in order to tell the story I wanted to tell, I needed a two-part structure: the present-day story of Sofie uncovering the mystery, and then the biography of Lara, which takes us into the origins of that mystery.

Q: At its heart, Our American Friend is the story of two women from wildly different backgrounds who must trust each other. How do you see the relationship between Sofie and Lara? Was one character more enjoyable to write?

A: Their relationship definitely evolves over time. Lara is a cold and private woman married to a cruel and greedy man. At the beginning, Sofie is wary of her. But as they spend more time together, Sofie sees that Lara is more conflicted and complicated than she might appear, and that there’s a story behind this conflict. She starts to unravel the threads of Lara’s pain. Do they wind up being friends? I’ve never been sure about that word. I think their relationship is both deeper and more fraught than a friendship.

I loved writing both women, for very different reasons. They both wound up surprising me.

Q: Our American Friend explores questions of complicity, loyalty, and objectivity; as an author you must have found yourself wondering how you would react when put in either Sofie or Lara’s positions. Did you come to any conclusions? Did your position change during the course of your writing?

A: I wondered it all the time! Writing about Sofie’s journey was, actually, my way of asking myself some of those questions. Does a person like Lara Caine deserve my empathy or attention? Does telling her story imply that I “approve” of her story? Am I creating harm in the world by asking people to understand her? These are slippery questions. Even by the end of the book, I didn’t feel that I had found any answers. But I think the act of asking those questions is still important, even if we can’t be sure.

Q: Did you have a favorite scene or section in the novel which came to you most easily? Was there a part that was more difficult to write than others?

A: I loved writing the scenes between Sofie and her sister, Jenna[HK6] . They were looser, more restful, and less pressurized. In so much of the story, a character is forced to wonder: Is this person trying to hurt me? Is this person trying to manipulate me? But Sofie and Jenna love each other so much. Even when they disagree, the love is there. The trust is there.

The opposite also holds true: the hardest scenes to write were those in which trust is questioned. When everything feels uncertain and a character has to make an important high-stakes decision. Those scenes were very stop and start, and took a lot of revision.

Q: Did you always know you wanted to be a writer? How did the experience of writing Our American Friend compare to your previous novels?

A: I’ve always loved reading. Books have kept me company for my entire life! When I was a little kid, like eight or nine, I dreamed of being a writer. And then, interestingly, for a long time I thought I couldn’t be a writer. That maybe I wasn’t talented or special enough. It took many years for that old confidence to come back to me—but eventually it did!

With all of my novels, I’ve done a huge amount of rewriting. It’s not until I’m finished with the first draft that I actually understand what the story is about. At that point, the draft is a mess! I have to throw it out and rebuild it from scratch. In the second draft, thankfully, things are a little easier. They move a little quicker. I finally know what I’m trying to say.

Q: What do you hope readers will take away from finishing Our American Friend?

A: I hope Our American Friend gives you a good dose of escapism. I hope it whisks you away to another world and lets you forget about the stresses of your own life for a little while! But, at the same time, I also hope that this book raises certain questions. That it makes you wonder what you might do if you were in Sofie or Lara’s shoes. A morally provocative page-turner: that’s always my goal.

Q: Do you have any advice for aspiring novelists?

A: My best advice is to read. To read everything! To expose yourself to writers and ideas from all different backgrounds, cultures, and genres. To read books that push your boundaries, that disrupt your understanding of the world, and that raise uncomfortable questions. To be a good writer, you first have to be a good reader and a good thinker. The learning never ends. Only when you are challenging yourself are you growing.

Why We Love It

“This is Anna Pitoniak’s third novel, and I’m thrilled to say that Our American Friend is her best book yet.

While on its face, Our American Friend is a very different book from her first two novels, which were coming of age stories set in the worlds of finance and broadcast news, respectively, all three of her novels are about characters who are thrust into high-stakes situations—and how they choose to relate to one another within those circumstances. Who, or what, are they loyal to? Who do they choose to betray, when and why do they decide to lie? How does ambition factor in? How does love?

Our American Friend explores all of these themes, but in the propulsive package of a feminist spy thriller, a story of an unlikely friendship—and a subsequent betrayal—and a star-crossed romance that moved me to tears.”

—Carina G., Senior Editor, on Our American Friend

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (February 28, 2023)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982158965

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Our American Friend Trade Paperback 9781982158965

- Author Photo (jpg): Anna Pitoniak Andrew Bartholomew(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit