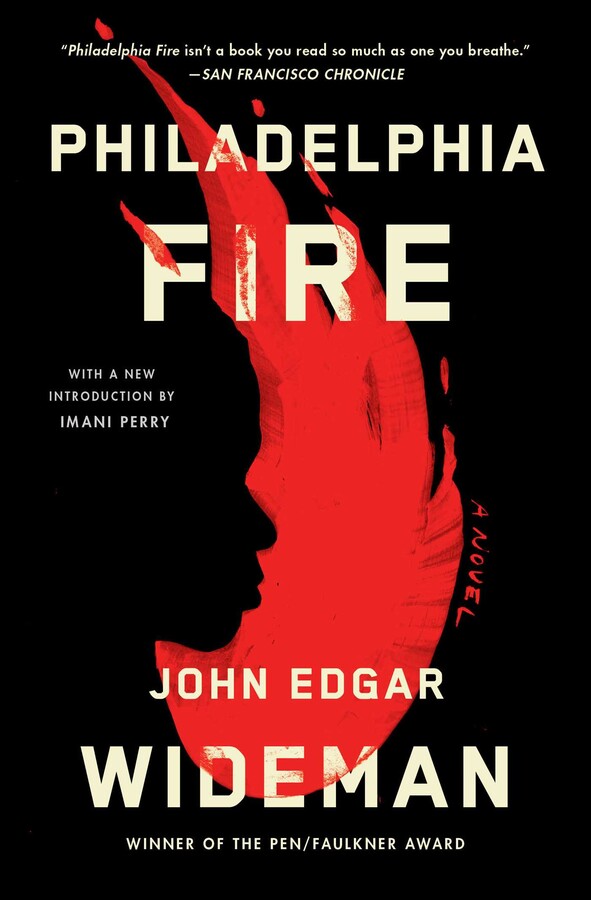

Philadelphia Fire

A Novel

LIST PRICE $17.00

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

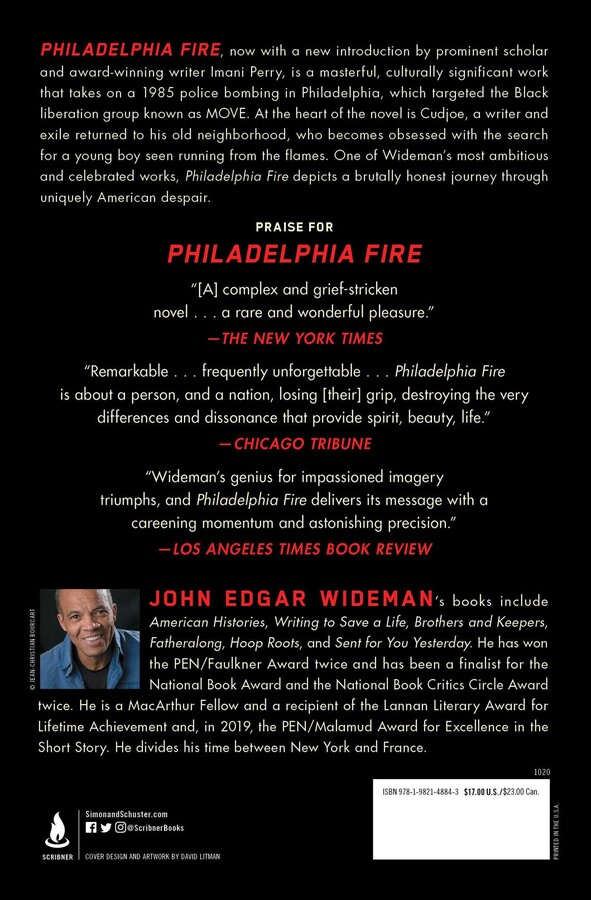

In 1985, police bombed a West Philadelphia row house owned by the Afrocentric cult known as Move, killing eleven people and starting a fire that destroyed sixty other houses. At the heart of Philadelphia Fire is Cudjoe, a writer and exile who returns to his old neighborhood after spending a decade fleeing from his past, and who becomes obsessed with the search for a lone survivor of the event: a young boy seen running from the flames.

Award-winning author John Edgar Wideman brings these events and their repercussions to shocking life in this seminal novel. “Reminiscent of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man” (Time) and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, Philadelphia Fire is a masterful, culturally significant work that takes on a major historical event and takes us on a brutally honest journey through the despair and horror of life in urban America.

Excerpt

On a day like this the big toe of Zivanias had failed him. Zivanias named for the moonshine his grandfather cooked, best white lightning on the island. Cudjoe had listened to the story of the name many times. Was slightly envious. He would like to be named for something his father or grandfather had done well. A name celebrating a deed. A name to stamp him, guide him. They’d shared a meal once. Zivanias crunching fried fish like Rice Krispies. Laughing at Cudjoe. Pointing to Cudjoe’s heap of cast-off crust and bones, his own clean platter. Zivanias had lived up to his name. Deserted a flock of goats, a wife and three sons up in the hills, scavenged work on the waterfront till he talked himself onto one of the launches jitneying tourists around the island. A captain soon. Then captain of captains. Best pilot, lover, drinker, dancer, storyteller of them all. He said so. No one said different. On a day like this when nobody else dared leave port, he drove a boatload of bootleg whiskey to the bottom of the ocean. Never a trace. Not a bottle or bone.

Cudjoe watches the sea cut up, refusing to stay still in its bowl. Sloshing like the overfilled cup of coffee he’d transported this unsteady morning from marble-topped counter to a table outdoors on the cobblestone esplanade. Coffee cooled in a minute by the chill wind buffeting the island. Rushes of wind and light play with rows of houses like they are skirts. Lift the whitewashed walls from their moorings, billow them as strobe bursts of sunshine bounce and shudder, daisy chains of houses whipping and snapping as wind reaches into the folds of narrow streets, twisting tunnels and funnels of stucco walls, a labyrinth of shaky alleyways with no roof but the Day-Glo blue-and-gray crisscrossed Greek sky hanging over like heavy, heavy what hangs over in the game they’d played back home in the streets of West Philly.

Zivanias would hold his boat on course with his foot. Leaning on a rail, prehensile toes snagged in the steering wheel, his goatskin vest unbuttoned to display hairy chest, eyes half shut, humming an island ballad, he was sailor-king of the sea, a photo opportunity his passengers could not resist. Solitary females on holiday from northern peninsulas of ice and snow, secretaries, nurses, schoolteachers, clerks, students, the druggies who’d sold dope and sold themselves to get this far, this last fling at island sun and sea and fun, old Zivanias would hook them on his horny big toe and reel them in. Plying his sea taxi from bare-ass to barer-ass to barest-ass beach, his stations, his ports of call along the coast.

But not today. No putt-putting around the edges of Mykonos, no island hopping. Suicide on a day like this to attempt a crossing to Delos, the island sacred to Apollo where once no one was allowed to die or be born. No sailing today even with both hands on the wheel and all ten toes gripping the briny deck. Chop, chop sea would eat you up. Swallow your little boat. Spew it up far from home. Zivanias should have known better. Maybe he did. Maybe he couldn’t resist the power in his name summoning him, Zivanias, Zivanias. Moonshine. Doomshine. Scattered on the water.

Cudjoe winces. A column of feathers and stinging grit rises from the cobblestones and sluices past him. Wind is steady moan and groan, a constant weight in his face, but it also bucks and roils and sucks and swirls madly, sudden stop and start, gust and dust devil and dervishes ripping the world apart. Clouds scoot as if they’re being chased. Behind him the café window rattles in its frame. Yesterday at this same dockside table he’d watched the sunset. Baskets of live chickens unloaded. Colors spilled on the sea last evening were chicken broth and chicken blood and the yellow, wrinkled skin of plucked chickens. Leftover feathers geyser, incongruous snowflakes above stacks of empty baskets. The island exiled today. Jailed by its necklace of churning sea. No one could reach Mykonos. No one could leave. Dead sailorman Zivanias out there sea-changed, feeding the fish. Cudjoe’s flight home disappearing like the patches of blue sky. Sea pitches and shivers and bellows in its chains. Green and dying. Green and dying. Who wrote that poem. Cudjoe says the words again, green and dying, can’t remember the rest, the rest is these words repeating themselves, all the rest contained in them, swollen to bursting, but they won’t give up the rest. Somebody keeps switching a light on and off. Gray clouds thicken. White clouds pull apart, bleed into the green sea. A seamless curtain of water and sky draws tighter and tighter. The island is sinking. Sea and wind wash over its shadow, close the wound.

Take that morning or one like it and set it down here in this city of brotherly love, seven thousand miles away, in a crystal ball, so it hums and gyrates under its glass dome. When you turn it upside-down, a thousand weightless flakes of something hover in the magic jar. It plays a tune if you wind it, better watch out, better not cry. Cudjoe cups his hands, fondles the toy, transfixed by the simplicity of illusion, how snow falls and music tinkles again and again if you choose to play a trick on yourself. You could stare forever and the past goes on doing its thing. He dreams his last morning on Mykonos once more. If you shake the ball the flakes shiver over the scene. Tiny white chicken feathers. Nothing outside the sealed ball touches what’s inside. Hermetic. Unreachable. Locked in and the key thrown away. Once again he’ll meet a dark-haired woman in the café that morning. Wind will calm itself, sky clear. The last plane shuttles him to the mainland. Before that wobbly flight he’ll spend part of his last day with her on the beach. There will be a flash of fear when she rises naked from the sea and runs toward him, crowned by a bonnet of black snakes, arms and legs splashing showers of spray, sun spots and sun darts tearing away great chunks of her so he doesn’t know what she is. They’ll lie together on the sand. She will teach him the Greek for her body parts. Hair is… eyes are… nose is… the Greek words escaping him even as he hears them. But he learns the heat of her shoulders, curve of bone beneath the skin. No language she speaks is his. She doubles his confusion. He forgets how to talk. When she tests him, pointing to his eyes, he traces with a fingertip the pit of bone containing hers. He closes his eyes. He is blind. Words are empty sounds. Saying them does not bring her back. He’d tasted salt when he’d matched his word for lips with hers.

Cudjoe is remembering the toy from his grandmother’s cupboard. A winter scene under glass. Lift it by its black plastic base, turn it upside-down, shake it a little, shake it, don’t break it, and set the globe down again watch the street fill up with snow the little horse laugh to see such a sight and the dish run away with the spoon. He wonders what happened to his grandmother’s souvenir from Niagara Falls. When did she buy it? Why did he always want to pry it open and find the music and snow wherever they were hiding when the glass ball sat still and silent? He wanted to know but understood how precious the trinket was to his grandmother. She would die if he broke it. She lay in bed, thinner every day the summer after the winter his grandfather died. She was melting away. Turning to water which he mopped from her brow, from her body parts when he lifted the sheets. Could he have saved her if he’d known the Greek for arms and legs? His grandmother’s sweaty smell will meet him when he returns to the house on Finance and walks up the front-hall stairs and enters the tiny space where he cared for her that summer she melted in the heat of grief. Her husband of forty years dead, her flesh turning to water. Sweat is what gives you life. He figured that out as life drained from her. Her dry bones never rose from the bed. You could lift her and arrange her in the rocking chair but life was gone. He’d wiped it from her brow, her neck. Dried the shiny rivers in her scalp. Leg is… arm is… He learned the parts of a woman’s body caring for her, the language of sweat and smell they spoke. He had been frightened. He knew everything and nothing. Why was he supposed to look away from her nakedness when his aunts bathed her? He loved her. Shared her secrets. If he sat in the rocker keeping watch while she slept, she would not die.

The crystal ball long gone. He can’t recall the first time he missed it. Nothing rests in the empty cup of his hands. Not the illusion of a chilly winter day, not snowfall or a dark-haired woman’s face, her skin brown and warm as bread just out the oven. Ladybug, Ladybug. Fly away home. Your house is on fire. Your children burning. He is turning pages. Perhaps asleep with a book spread-eagled on his lap, the book he wishes he was writing, the story he crossed an ocean to find. Story of a fire and a lost boy that brought him home.

He had taped what she said. She is Margaret Jones now, Margaret Jones again. Her other names are smoke curling from smashed windowpanes of the house on Osage. A rainbow swirl of head kerchief hides her hair, emphasizes the formal arrangement of eyes, nose, lips embedded in blemishless yellow-brown skin. No frills, no distractions, you see the face for what it is, severe, symmetrical, eyes distant but ready to pounce, flared bulk of nose, lips thick and strong enough to keep the eyes in check.

She thinks she knows people who might know where the lost child could be. And she is as close to the boy as he’s come after weeks of questions, hanging around, false leads and no leads, his growing awareness of getting what he deserved as he was frowned at and turned away time after time. The boy who is the only survivor of the holocaust on Osage Avenue, the child who is brother, son, a lost limb haunting him since he read about the fire in a magazine. He must find the child to be whole again. Cudjoe can’t account for the force drawing him to the story nor why he indulges a fantasy of identification with the boy who escaped the massacre. He knows he must find him. He knows the ache of absence, the phantom presence of pain that tricks him into reaching down again and again to stroke the emptiness. He’s stopped asking why. His identification with the boy persists like a discredited rumor. Like Hitler’s escape from the bunker. Like the Second Coming.

What Cudjoe has discovered is that the boy was last seen naked skin melting, melting, they go do-do-do-do-do-do-do like that, skin melting Stop kids coming out stop stop kids coming out skin melting do-do-do-do-do-do like going off—like bullets were going after each other do-do-do-do fleeing down an alley between burning rows of houses. Only one witness. A sharpshooter on a roof who caught the boy’s body in his telescopic sight just long enough to know he’d be doomed if he pulled the trigger, doomed if he didn’t. In that terrible light pulsing from the inferno of fire-gutted houses the boy flutters, a dark moth shape for an instant, wheeling, then fixed forever in the crosshairs of the infrared sniperscoped night-visioned weapon trained on the alley. At the same instant an avalanche of bullets hammers what could be other figures, other children back into boiling clouds of smoke and flame. The last sighting reports the boy alone, stumbling, then upright. Then gone again as quickly as he appeared.

Cudjoe hears screaming stop stop kids coming out kids coming out as the cop sights down the blazing alley. Who’s screaming? Who’s adding that detail? Could a cop on a roof two hundred feet away from a ghost hear what’s coming from its mouth? Over crackling flames? Over volleys of automatic-weapons fire thudding into the front of the house, over the drum thump of heart, roar of his pulse when something alive dances like a spot of grease on a hot griddle there in the molten path between burning row houses? The SWAT-team rifleman can’t hear, barely sees what is quivering in the cross hairs. Is it one of his stinging eyelashes? He squints and the vision disappears. Did he pull the trigger? Only later as he’s interrogated and must account for rounds fired and unfired does it become clear to him that what he saw was a naked boy, a forked stick with a dick. No. No, I didn’t shoot then. Others shot. Lots of shooting when the suspects tried to break out of the house. But I didn’t shoot. Not then. Because what I seen was just a kid, with no clothes on screaming. I let him go.

Cudjoe reminds himself he was not there and has no right to add details. No sound effects. Attribute no motives nor lack of motive. He’s not the cop, not the boy.

Tape is rewinding on his new machine. The woman with the bright African cloth tied round her head had not liked him. Yet she was willing to talk, to be taped. She’d agreed to meet him again, this time in the park instead of the apartment of the mutual friend who’d introduced them. You know. Clark Park, Forty-third and Baltimore. He’d nodded, smiled, ready after an hour of listening and recording to say something about the park, about himself, but she’d turned away, out of her chair already, already out the door of Rasheed’s apartment, though her body lagged behind a little saying good-bye to him, hollering good-bye over her shoulder to Rasheed. She’d watched the tape wind from spool to spool as she’d talked. Rasheed had waited in another room for them to finish. Cudjoe might as well have been in there, too. He spoke only once or twice while she talked. Margaret Jones didn’t need him, care for him. She was permitting him to overhear what she told the machine. Polite, accommodating to a degree, she also maintained her distance. Five thousand miles of it, plus or minus an inch. The precise space between Cudjoe’s island and West Philly. Somehow she knew he’d been away, exactly how long, exactly how far, and that distance bothered her, she held it against him, served it back to him in her cool reserve, seemed unable ever to forgive it.

How did she know so much about him, not only her but all her sisters, how, after the briefest of conversations, did they know his history, that he’d married a white woman and fathered half-white kids? How did they know he’d failed his wife and failed those kids, that his betrayal was double, about blackness and about being a man? How could they express so clearly, with nothing more than their eyes, that they knew his secret, that he was someone, a half-black someone, a half man who couldn’t be depended upon?

He peels a spotty banana down to the end he holds. Bites off a hunk. Rewraps the fruit in its floppy skin and rests it on a paper towel beside the tape recorder. Spoons a lump of coffee-flavored Dannon yogurt into his mouth. The tastes clash. One too sweet. One too tart. The cloying overripe odor of unzipped banana takes over. In an hour he should be in the park. Will Ms. Jones show up? If he admits to her he doesn’t know why he’s driven to do whatever it is he’s trying to do, would she like him better? Should he tell her his dream of a good life, a happy life on a happy island? Would she believe him? Fine lines everywhere to negotiate. He knows it won’t be easy. Does she think he’s stealing from the dead? Is he sure he isn’t? Tape’s ready. He pushes the button.

… Because he was so sure of hisself, bossy, you know. The big boss knowing everything and in charge of everything and could preach like an angel, they called him Reverend King behind his back. Had to call him something to get his attention, you know. James didn’t sound right. He wasn’t a Jimmy or Jim. Mr. Brown wouldn’t cut it. Mr. Anything no good. Reverend King slipped out a couple times and then it got to be just King. King a name he answered to. Us new ones in the family had to call him something so we called him King because that’s what we heard from the others. Didn’t realize it kind of started as a joke. Didn’t realize by calling him something we was making him something. He was different. You acted different around him so he’d know you knew he was different. Then we was different.

He taught us about the holy Tree of Life. How we all born part of it. How we all one family. Showed us how the rotten system of this society is about chopping down the Tree. Society hates health. Society don’t want strong people. It wants people weak and sick so it can use them up. No room for the Life Tree. Society’s about stealing your life juices and making you sick so the Tree dies.

He taught us to love and respect ourselves. Respect Life in ourselves. Life is good, so we’re good. He said that every day. We must protect Life and pass it on so the Tree never dies. Society’s system killing everything. Babies. Air. Water. Earth. People’s bodies and minds. He taught us we are the seeds. We got to carry forward the Life in us. When society dies from the poison in its guts, we’ll be there and the Tree will grow bigger and bigger till the whole wide earth a peaceful garden under its branches. He taught us to praise Life and be Life.

We loved him because he was the voice of Life. And our love made him greater than he was. Made him believe he could do anything. All the pains we took. The way we were so careful around him, let him do whatever he wanted, let him order us around like we was slaves. Now when I look back I guess that’s what we was. His slaves. And he was king because we was slaves and we made him our master.

He was the dirtiest man I ever seen. Smell him a mile off. First time I really seen him I was on my way home from work and he was just sitting there on the stone wall in front of their house. Wasn’t really stone. Cinder blocks to hold in yard dirt. Stacked four or five high and a rusty kind of broken-down pipe fence running across the top of the blocks. Well, that’s where he was sitting, dangling his bare legs and bare toes, sprawled back like he ain’t got a care in the world. Smelled him long before I seen him. Matter of fact when I stepped down off the bus something nasty in the air. My nose curls and I wonder what stinks, what’s dead and where’s it hiding, but I don’t like the smell so I push it to the back of my mind cause nothing I can do about it. No more than I can stop the stink rolling in when the wind blows cross from Jersey. Got too much else to worry about at 5:30 in the evening. I’m hoping Billy and Karen where they supposed to be. Mrs. Johnson keep them till 5:00, then they supposed to come straight home. Weather turning warm. Stuffy inside the house already so I say OK youall can sit out on the stoop but don’t you go a step further till I’m home. Catch you gallivanting over the neighborhood it’s inside the house, don’t care if it’s a oven in there. Billy and Karen mind most the time, good kids, you know what I mean, but all it takes is one time not minding. You know the kinda trouble kids can get into around here. Deep trouble. Bad, bad trouble. One these fools hang around here give them pills. One these jitterbugs put his hands on Karen. I’m worried about that sort of mess and got dinner to fix and beat from work, too beat for any of it. My feet ache and that’s strange because I work at a desk and I’m remembering my mama keeping house for white folks. Her feet always killing her and here I am with my little piece of degree, sitting on my behind all day and my feet sore like hers. Maybe what it is is working for them damned peckerwoods any kind of way. Taking their shit. Bitterness got to settle somewhere don’t it? Naturally it run down to your feet. Anyway, I’m tired and hassled. Ain’t ready for no more nonsense. Can’t wait till Billy and Karen fed and quiet for the night, safe for the night, the kitchen clean, my office clothes hung up, me in my robe and slippers. Glass of wine maybe. One my programs on TV. Nothing but my own self to worry about.

When I step off the bus stink hits me square between the eyeballs. No sense wrinkling up my nose. Body got to breathe and thinking about what you breathing just make it worse so I starts towards home which is three and a half blocks from where I get off the Number 62. Almost home when I see a trifling dreadlocked man draped back wriggling his bare toes. Little closer to him and I know what’s dead, what’s walking the air like it ain’t had a bath since Skippy was a pup. Like I can see this oily kind of smoke seeping up between the man’s toes. He’s smiling behind all that hair, all that beard. Proud of his high self working toejam. I know it ain’t just him stinking up the whole neighborhood. It’s the house behind him, the tribe of crazy people in it and crazy dogs and loudspeakers and dirty naked kids and the backyard where they dump their business, but sitting the way he is on the cinder blocks, cocked back and pleased with hisself, smiling through that orangutan hair like a jungle all over his face, it’s like he’s telling anybody care to listen, this funk is mine. I’m the funk king sitting here on my throne and you can run but you can’t hide.

See, it’s personal then. Me and him. To get home I have to pass by him. His wall, his house, his yard. Either pass by or go way round out my way. Got my route home I’ve been walking twelve years. Bet you find my footprints in the pavement I been walking home from work that way so long. So I ain’t about to change just cause some nasty man sitting there like he’s God Almighty. Huh. Uh. This street mine much as it’s anybody’s. I ain’t detouring one inch out my way for nothing that wears britches and breathes. He ain’t nothing to me no matter how bad he smell, no matter if he blow up in a puff of black smoke cause he can’t stand his own self. Tired as my feet be at the end of the day I ain’t subjecting them to one extra step around this nasty man or his nasty house.

So I just trots on by like he ain’t there, like ain’t none of it there. Wall. Pipe he’s got his greasy arms draped over. House behind him and the nuts in it. You know. Wouldn’t give him the satisfaction. What I do do is stop breathing. Hold my breath till I’m past him, hold it in so long when I let it out on the next corner, I’m dizzy. But I’m past him and don’t give him the satisfaction. Tell the truth, I almost fainted before I made it up on the curb. And wouldn’t that have been a sight. Me keeling over in the street. He woulda had him a good laugh at that. Woulda told all them savages live with him. They could all have a good laugh together. The hounds. But what I care? Didn’t happen, did it? Strutted right past him like he wasn’t there. Didn’t even cross to the other side of Osage like I knew he was sitting there betting I would. Hoping I would so he could tell his tribe and they could all grin and hee-haw and put me on their loudspeakers.

No. No. Walked home the way I always walk home. Didn’t draw one breath for a whole block. Almost knocked myself out, but be damned if I’d give him the satisfaction.

Doesn’t make much sense, does it? Because the day I’m telling you about, the first time I seen him eyeball to eyeball, wasn’t much more than a year ago. Three months from that day I was part of his family. One his slaves that quick. Still am in a way. Even though his head’s tore off his body and his body burned to ash. See because even though he did it wrong, he was right. What I mean is his ideas were right, the thoughts behind the actions righteous as rain. He be rapping and he’d stop all the sudden, look over to one the sisters been a real strong church woman her whole life and say: Bet your sweet paddy boy Jesus amen that, wouldn’t he now? Teasing sort of, but serious too. He be preaching what Jesus preached except it’s King saying the words. Bible words only they issuing from King’s big lips. And you know he means them and you understand them better cause he says them black, black like him, black like you, so how the sister gon deny King? Tell that white fella Jesus stop pestering you. Tell him go on back to the desert and them caves where he belong.

Got to her Christian mind. Got to my tired feet. Who I been all the days of my life? A poor fool climb on a bus in the morning, climb down at night. What I got to show for it but sore feet, feet bad as my mama’s when, God bless her weary soul, we laid her to rest after fifty years cleaning up white folks’ mess. My life wasn’t much different from my mama’s or hers from her mama’s on back far as you want to carry it back. Out in the field at dawn, pick cotton the whole damned day, shuffle back to the cabin to eat and sleep so’s you ready when the conch horn blows next morning. Sheeet. Things spozed to get better, ain’t they? Somewhere down the line, it ought to get better or what’s the point scuffling like we do? Don’t have to squat in the weeds and wipe my behind with a leaf. Running water inside my house and in the supermarket I can buy thirty kinds of soda pop, twelve different colors of toilet paper. But that ain’t what I call progress. Do you? King knew it wasn’t. King just told the truth.

My Billy and Karen in school. Getting what they call an education. But what those children learn. Ask them where they come from, they give you the address of a house on Osage Avenue. Ask them what’s on their minds, they mumble something they heard on the TV. Ask them what color they are, they don’t even know that. Look them in the eye you know what they really thinking. Only thing they ever expect to be is you. Working like you for some white man or black man don’t make no difference cause all they pay you is nigger wages, enough to keep you guessing, keep you hungry, keep you scared, keep you coming back. Piece a job so you don’t never learn nothing, just keep you busy and too tired to think. But your feet think. They tell you every day God sends, stop this foolishness. Stop wearing me down to the nubs.

Wasn’t like King told me something new. Wasn’t like I had a lot to learn. Looked round myself plenty times and said, Got to be more to it than this. Got to be. King said out loud what I been knowing all along. Newspapers said King brainwashing and mind control and drugs and kidnapping people turn them to zombies. Bullshit. Because I been standing on the bank for years. Decided one day to cross over and there he was, the King take my hand and say, Welcome, come right in, we been waiting. Held my breath walking past him and wasn’t more than a couple months later I’m holding my breath and praying I can get past the stink when he’s raising the covers off his mattress and telling me lie down with him. By then stink wasn’t really stink no more. Just confusion. A confused idea. An idea from outside the family, outside the teachings causing me to turn my nose up at my own natural self. Felt real ashamed when I realized all of me wasn’t inside the family yet. I damned the outside part. Left it standing in the dark and crawled up under the covers with King cause he’s right even if he did things wrong sometimes, he’s still right cause ain’t nothing, nowhere any better.

Cudjoe stops the tape. Was Margaret Jones still in love with her King, in love with the better self she believed she could become? He’d winced when she described King lifting the blanket off his bed. Then Cudjoe had leaned closer, tried to sneak a whiff of her. Scent of the sacred residue. Was a portion of her body unwashed since the holy coupling? She had looked upon the King’s face and survived. Cudjoe sees a rat-gnawed, bug-infested mattress spotted with the blood of insects, of humans. Her master’s face a mask of masks. No matter how many you peel, another rises, like the skins of water. Loving him is like trying to solve a riddle whose answer is yes and no. No or yes. You will always be right and wrong.

Not nice to nose under someone’s clothes. Cudjoe knows better. He had cheated, sniffing this witness like some kind of evil bloodhound.

The spools spin:

My kids wouldn’t have nothing to do with King. When I moved into his house they ran away. I think Karen might have moved with me but Billy, thank goodness, wouldn’t let her. Went to my sister’s in Detroit. Then Detroit drove to Philly to rescue me. A real circus. I’m grateful to God nobody was hurt. King said, You nebby, bleached negroes come round here hassling us again I’ll bust you up. He was just woofing. But he sounds like he means every word and I’m standing in the doorway behind him amening what he’s saying. My own sister and brother-in-law, mind you. Carl worked at Ford. My sister Anita a schoolteacher. Doing real good in Detroit and they drove all the way here to help me but I didn’t want no help. Thought all I needed was King. They came out of love but I hated them for mixing in my business. Hated them for taking care of Karen and Billy. See, I believed they were part of the system, part of the lie standing in the way of King’s truth. The enemy. The ones trying to kill us. Up there in their dicty Detroit suburb living the so-called good life.

Cudjoe fast-forwards her story. Would she tell more about the boy this time? Or would the tape keep saying what it had said last time he listened.

… Had the good sense not to sell my house when I moved out. Rented it. Gave the rent money to King. If I’d sold it, would’ve give all the money to him. Wouldn’t have nothing now. No place for Billy and Karen to come back to, if they coming back. Don’t want them here yet. City spozed to clean up and rebuild but you see the condition things in. My place still standing. Smoke and water tore it up inside but at least it’s still standing. Next block after mine looks like pictures I seen of war. Look like the atom bomb hit. Don’t want Karen and Billy have to deal with what the bombs and fire and water did. They see the neighborhood burned down like this, they just might blame me. Because like I said, I was one of them. King’s family. Rented my house and moved in with them. Yes. But for the grace of God coulda been me and my kids trapped in the basement, bar-b-qued to ash.

I still can’t believe it. Eleven people murdered. Babies, women, didn’t make no nevermind to the cops. Eleven human beings dead for what? Tell me for what. Why did they have to kill my brothers and sisters? Burn them up like you burn garbage? What King and them be doing that give anybody the right to kill them? Wasn’t any trouble till people started coming at us. Then King start to woofing to keep folks off our case. Just woofing. Just talk. You ask anybody around here, the ones still here or the ones burnt out, if you can find them. Ask them if King or his people ever laid a hand on anybody. You find one soul say he been hurt by one of us he’s a lying sack of shit.

King had his ways. We all had our ways. If you didn’t like it, you could pass on by. That’s all anybody had to do, pass us by. Hold your nose, your breath if you got to, but pass on by and leave us alone, then we leave you alone and everybody happy as they spozed to be.

The boy?

Cudjoe is startled by his voice on the tape, asking the question he’s thinking now. Echo of his thought before he speaks it.

The boy?

Little Simmie. Simmie’s what we called him. Short for Simba Muntu. Lion man. That’s what Clara named him when she joined King’s people. Called herself Nkisa. She was like a sister to me. We talked many a night when I first went there to live. Little Simmie her son. So afterwhile I was kind of his aunt. All of us family, really. Simmie’s an orphan now. His mama some of those cinders they scraped out the basement of the house on Osage and stuffed in rubber bags. I was behind the barricade the whole time. Watched it all happening. Almost lost my mind. Just couldn’t believe it. I saw it happening and couldn’t believe my eyes.

Those dogs carried out my brothers and sisters in bags. And got the nerve to strap those bags on stretchers. Woman next to me screamed and fainted when the cops start parading out with them bags strapped on stretchers. Almost fell out my ownself watching them stack the stretchers in ambulances. Then I got mad. Lights on top the ambulances spinning like they in a hurry. Hurry for what? Those pitiful ashes ain’t going nowhere. Nkisa and Rhoberto and Sunshine and Teetsie. They all gone now, so what’s the hurry? Why they treating ash like people now? Carrying it on stretchers. Cops wearing gloves and long faces like they respect my brothers and sisters now. Where was respect when they was shooting and burning and flooding water on the house? Why’d they have to kill them two times, three times, four times? Bullets, bombs, water, fire. Shot, blowed up, burnt, drowned. Nothing in those sacks but ash and guilty conscience.

What they carried out was board ash and wall ash and roof ash and hallway-step ash and mattress ash and the ash of blankets and pillows, ashes of the little precious things you sneaked in with you when you went to live with King because he said, Give it up, give up that other life and come unto me naked as the day you were born. He meant it too. Never forget being buck naked and walking down the rows of my brothers and sisters each one touch me on my forehead. Shivering. Goose bumps where I forgot you could get goose bumps. Thinking how big and soft I was in the behind and how my titties must look tired hanging down bare. But happy. Oh so happy. Happy it finally come down to this. Nothing to hide no more. Come unto me and leave the world behind. Like a newborn child.

My brothers and sisters and the babies long gone and wasn’t much else in the house to make ash, so it’s walls and floors in those bags, the pitiful house itself they carting away in ambulances.

His mother died in the fire.

All dead. All of them dead.

But he escaped.

She pushed him and two the other kids out the basement window. Simmie said he was scared, didn’t want to go. Nkisa had to shove him out the window. He said she threw him and then he doesn’t remember a thing till he wakes up in the alley behind the house. Must of hit his head on something. He said he was dreaming he was on fire and took off running and now he doesn’t know when he woke up or when he was dreaming or if the nightmare’s ever gon stop. Poor Simmie an orphan now. Like my Karen and Billy till I got myself thinking straight again. Till I knew I couldn’t put nobody, not even King, before my kids. They brought me back to the world. And it’s as sorry-assed today as it was when I walked away. Except it’s worse now. Look round you at the neighborhood. Where’s the houses, the old people on their stoops, the children playing in the street? Nobody cares. The whole city seen the flames, smelled the smoke, counted the body bags. Whole world knows children murdered here. But it’s quiet as a grave, ain’t it? Not a mumbling word. People gone back to making a living. Making some rich man richer. Losing the only thing they got worth a good goddamn, the children the Lord gives them for free, and they ain’t got the good sense to keep.

You’ve talked to Simmie?

Talked to people talked to him.

Do you know where he is?

I know where to find somebody who might know where he is. Why do you want to know?

I need to hear his story. I’m writing a book.

A book?

About the fire. What caused it. Who was responsible. What it means.

Don’t need a book. Anybody wants to know what it means, bring them through here. Tell them these bombed streets used to be full of people’s homes. Tell them babies’ bones mixed up in this ash they smell.

I want to do something about the silence.

A book, huh. A book people have to buy. You want Simmie’s story so you can sell it. You going to pay him if he talks to you?

It’s not about money.

Then why you doing it?

The truth is, I’m not really sure.

You mean you’ll do your thing and forget Simmie. Write your book and gone. Just like the social workers and those busybodies from the University. They been studying us for years. Reports on top of reports. A whole basement full of files in the building where I work. We’re famous.

Why don’t you leave poor Simmie alone, mister? He’s suffered enough. And still suffering. Nightmares. Wetting the bed. Poor child’s trying to learn what it’s like to live with people ain’t King’s people.

Will you help me find him?

I don’t think so.

Can we meet again at least? Talk some more?

Saturday maybe. That will give me time to ask around. Not here. In Clark Park. I don’t like being in here with that machine sucking up all the air.

I’ll meet you anywhere. Anytime. Tape or no tape.

Saturday morning. Clark Park.

What time, Saturday?

Early.

I’ll be there.

I bet you will. Tell you a secret, though, my feelings won’t be hurt if you ain’t.

Clark Park. Forty-third and Osage. Saturday early. I’ll be there.

One more thing… is that damned machine still running?

Yes… no.

Click

If the city is a man, a giant sprawled for miles on his back, rough contours of his body smothering the rolling landscape, the rivers and woods, hills and valleys, bumps and gullies, crushing with his weight, his shadow, all the life beneath him, a derelict in a terminal stupor, too exhausted, too wasted to move, rotting in the sun, then Cudjoe is deep within the giant’s stomach, in a subway-surface car shuddering through stinking loops of gut, tunnels carved out of decaying flesh, a prisoner of rumbling innards that scream when trolleys pass over rails embedded in flesh. Cudjoe remembers a drawing of Gulliver strapped down in Lilliput just so. Ropes staked over his limbs like hundreds of tiny tents, pyramids pinning the giant to the earth. If the city is a man sprawled unconscious drunk in an alley, kids might find him, drench him with lighter fluid and drop a match on his chest. He’d flame up like a heap of all the unhappy monks in Asia. Puff the magic dragon. A little bald man topples over, spins as flames spiral up his saffron robe. In the streets of Hue and Saigon it had happened daily. You watched priests on TV burst into fireballs, roll as they combusted, a shadow flapping inside the flaming pyre. You thought of a bird in there trying to get out. You wondered if the bird was a part of the monk refusing to go along with the program. A protest within the monk’s protest. Hey. I don’t want nothing to do with this crazy shit. Wings get me out of here. Screeching and writhing as hot gets hotter, a scarecrow in the flame’s eye.

Same filthy-windowed PTC trolley car carries you above and below ground, in and out of flesh, like a needle suturing a wound. You hear an echo of wind and sea, smell it. As you ride beneath city streets there are distant explosions, muffled artillery roar and crackle of automatic weapons, sounds of war you don’t notice in the daylight world above. Down here no doubt the invisible warfare is real. You are rattling closer to it. It sets the windows of the trolley vibrating. Around the next blind curve the firefight waits to engulf you.

Above the beach at Torremolinos was another city of tunnels and burrows. Like a termite mound. Once, instead of following the shore path, he’d taken the vertical shortcut from beach to town. Haphazard steps hacked from rock, worn smooth by a million bare feet. You couldn’t see very far ahead or behind as you climbed up the cliff. Quickly the tourists baking like logs on the beach disappeared as you picked your way through a warren of dugout houses, the front stoops of some being the stations that formed a pathway from beach back up to hotels, shops and restaurants. Children sat at the mouths of caves and you planted your bare feet over, under and around their bare bodies, afraid of contamination, embarrassed by proximity, trespass. Bony gypsy children. Eyes dark as mirrors draped with black cloth. Eyes that should flash and play, be full of curiosity or mischief, but stare past you, through you. Riding these trains sunken in the earth, the sound of the sea waits in ambush. Near and far. Turn a corner and there sits one of these world hunger poster children silently begging to be something other than an image of disaster. Fingers of rib bone grasp the swollen belly like it’s a spoiled toy.

He recalls the sound of waves lapping the pilings, breaking and shimmying slow motion against a golden slice of beach three hundred yards below the outcropping of stone where he had paused. He’s naked except for bikini briefs, a gaudy towel slung like a bandolier over his shoulder. He’s ashamed of his skin, its sleekness, its color, the push of his balls against the flimsy pouch of black nylon. No pockets to empty, no language to confess his shame. He couldn’t make things right for the hollow-eyed, big-bellied children even if he had a thousand pockets and dumped silver from every one and the coins sparked and scintillated like the flat sea when a breath of wind passes over it, sequins, a suit of lights rippling to the horizon. From where he’d stood on the steep cliffside, eyes stinging from shame at having everything and nothing to give, the sea reached him as whisper, the same insinuating murmur that can seep from under his bed at night in this city thousands of miles away, that can squeeze from behind a picture frame on a wall, that hums in this subway tunnel miles beneath the earth.

He’ll tell Margaret Jones we’re all in this together. That he was lost but now he’s found.

I could smell the smoke five thousand miles away. Hear kids screaming. We are all trapped in the terrible jaws of something shaking the life out of us. Is that what he’d tell her? Is that why he’s back? Runagate, runagate, fly away home / Your house’s on fire and your children’s burning.

Should he admit to her he’d looked into the eyes of those gypsy children and shrugged, turned his hands inside out? The pale emptiness of his palms flashed like a minstrel’s white gloves, a silent-movie charade so he could pick his way in peace past stick legs and stick arms, the long feet that looked outsize because they sprouted first then nothing else grew. Big heads, big feet. Everything in between wasted away, siphoned into the brutal swell of their bellies. Skin the color of his, the color those tourists down on the beach dreamed of turning.

The subway takes you under ground, under the sea. When the train slows down for a station you can see greenish mold, sponge-like algae, yellow and red speckling the dark stones. Sometimes you hear the rush of water behind you flooding the tunnel, chasing your lighted bubble, rushing closer and closer each time the train halts. Damp, slimy walls the evidence of other floods, other cleansings, guts of the giant flushed clear of debris. He groans, troubled in his sleep as his bowels contract and shudder from the sudden passage of icy water.

When Cudjoe’s aboveground, heading toward Clark Park, the sidewalk’s unsteady under his feet. Should he be swimming or flying or crawling.

He will explain to Margaret Jones that he must always write about many places at once. No choice. The splitting apart is inevitable. First step is always out of time, away from responsibility, toward the word or sound or image that is everywhere at once, that connects and destroys.

Many places at once. Tromping along the sidewalk. In the air. Underground. Astride a spark coughed up by the fire. Waterborne. Climbing stone steps. To reach the woman in the turban, the boy, he must travel through those other places. Always moving. He must, at the risk of turning to stone, look back at his own lost children, their mother standing on a train platform, wreathed in steam, in smoke. An old-fashioned locomotive wheezes and lurches into motion. His wife waves a handkerchief wet with tears. One boy grasps the backs of her legs. The other sucks his thumb with a fold of her skirt that shows off her body’s sweet curves. His sons began in that smooth emptiness between her legs. They hide and sniffle, clutch handfuls of her silky clothes. It hurts him to look, hurts him to look away. Antique station he’s only seen in movies. A new career for his wife and sons. Wherever they are, he keeps them coming back to star in this scene. Waving. Clinging. But it’s the wrong movie. He’s not the one leaving. All aboard, all aboard. Faces pressed to the cold glass. Caroline had never owned a silk handkerchief, let alone a long silky skirt.

A trolley begins its ascent of Woodland Avenue, the steep curve along the cemetery where rails are bedded in cobblestones older than anything around them. A fence of black spears seven feet tall guards the neat, green city of the dead. When you choose to live in a city, you also are choosing a city to die in. A huge rat sidles over the cobbles, scoots across steel tracks, messenger from one domain to the other, the dead and living consorting in slouched rat belly.

Teresa, the barmaid once upon a time in Torremolinos, would listen to anything you had to say, as long as you bought drinks while you said it. Beautiful and untouchable, she liked to shoot rats at night after work, in the wee hours neither light nor dark over on the wrong side of town, in garbage dumps, the pits dug for foundations of luxury hotels, aborted high rises never rising any higher than stacks of debris rimming the edges of black holes. She’d hide in the shadows and wait for them to slink into exposed areas. Furry, moonlit bodies, sitting up like squirrels, a hunk of something in their forepaws, gnawing, quivering, profiled just long enough for her to draw a bead between their beady eyes. She never missed.

She was English. Or had lived in England long enough to acquire a British accent, a taste for reggae. Teresa never took Cudjoe seriously. He could amuse her, tease out her smile, but she never encouraged him to go further. She knew his habits—endless shots of Felipe II, determined assaults on each new batch of female tourists—and he knew she shot rats in the old quarter gypsies had inhabited before they were urban-removed.

He’d daydream of leaving the bar with Teresa, her alabaster skin luminous in the fading moonlight. They were survivors. No one else in the streets, the only sound their footfalls over wooden sidewalks, then padding through dusty alleys as they entered the ghetto. He’d watch her do her Annie Oakley thing. Her unerring aim. Her face pinched into a mask of concentration as she sights down the barrel. When she tires of killing, when she leans her rifle against a broken wall and huddles in her own skinny, pale arms, he’ll create himself out of the shadows, wrap her in his warmth, the heat of his body he’s been hoarding while she shot. He loves this moment when she’s weak and exhausted, the pallor of her skin, the cold in her bones, the starry distance of all those nights at the bar when he made her smile but could trick nothing more from those sad eyes. Yes. Take her in the stillborn shell of a building that is also the grave of a gypsy hovel, abandoned when the urban gypsies fled to join their brethren in caves above the sea. Make love to her in the ruins that had never been a city, ruins that were once a wish for a city, a mile-high oasis of steel and glass and rich visitors. Surprise her and take her there, loving her to pieces while rats scuttle from the darkness to eat their dead.

Yes. Clark Park. He knew the location of Clark Park. He’d nodded at Margaret Jones. Yes, I know Clark Park. He’d beaten up his body many a day on the basketball court there. Drank wine and smoked reefer with the hoop junkies many a night after playing himself into a stupor. Clear now what he’d been trying to do. Purge himself. Force the aching need for Caroline and his sons out of his body. Running till his body was gone, his mind whipped. Till he forgot his life was coming apart. Keep score of the game, let the rest go. The park a place to come early and stay late, punish the humpty-dumpty pieces of himself till they’d never want to be whole again.

Clark Park where he’d see a face like Teresa’s. A woman sat in the grass, on a slope below the asphalt path circling the park, in a bright patch of early-morning sunshine. She was staring at the hollow’s floor, a field tamped hard and brown by countless ball games. This woman who could be Teresa, who would be Teresa until Cudjoe satisfied himself otherwise, rested her chin on her drawn-up knees. No kids playing in the hollow, no dog walkers strolling on the path, just the two of us, Cudjoe had thought as he stopped and ambled down the green slope, lower than she was, so he could check out her face. He’ll smile, one early bird greeting another. Pass on if she’s a stranger.

Under her skimpy paisley dress, the woman was naked. She hugged her legs to her chest. Goose bumps prickled her bare loins. At the center of her a dark crease, a spray of curly hairs, soft pinch of buttocks. Cudjoe expected her to raise her chin off her knees, snap her legs straight, but she remained motionless, staring at the hollow. It could be Teresa’s face perched on the woman’s bare knees, a perfect match even though the body bearing it no way Teresa’s. But still it could be Teresa’s face. Right head, wrong body, like a sphinx. The eyes are dreamy, express a vulnerability Teresa never exposed. Teresa’s eyes were mirrors. You saw yourself, your unhappy secrets in them. Nothing in Teresa’s gaze suggested you could change her or change yourself. This woman, girl in Clark Park whose face was Teresa’s, whose body was compact, generously fleshed where Teresa was lithe and taut, this woman who let him see under her dress, had finally smiled down at him over her knees, a smile saying no more or less than this gift of sun feels good and I’m content to share it.

Then she had leaned backward catching her weight on her arms, knees steepled, eyes closing as she tilted her forehead into the light filtering through the trees. Cudjoe’s throat had tightened; he was afraid to swallow, to move an inch. He stared at the dark hinge between her legs. Though she seemed unconcerned by his presence, she wasn’t ignoring him. She was stretching, yawning, welcoming, returning to him after centuries of sleep. She’d chosen her spot and he was part of it, so nothing was foreign, nothing could disturb this moment of communion when what she was was boundless, new, Eve to his Adam, Cudjoe had told himself, half-believing, as he peered into the crack between her legs, the delicate pinks, soft fleece. Born again.

Her green-and-white minidress clearly an afterthought. Didn’t matter to her if it was off or on. She rolled slowly onto her side. From where Cudjoe stood the dress disappeared except for a green edging along the top of one bare flank. Neat roundness of her buttocks, graceful drape of thighs glowed in soft morning light. He couldn’t see a face now. Teresa disintegrates in the smoky shafts of sunlight painting the bank. Above him the remnant of a statue, a woman perfectly formed from marble.

He’d been stuck. Like a fly in honey. He couldn’t look away. Couldn’t go on about his business. What was he looking for then, now as he remembers her, remembers her wisp of dress and the sun, his throat dry, loins filling up, growing so heavy he believed he was sinking into the ground, remembering how she was Teresa, then she wasn’t, then she was, and the loud clanking of trolleys up Woodland, down Baltimore, cables popping, laughing at himself, believing none of it was real? At some point she’d risen, awkward, stiff from sitting too long. A flash of red-dimpled white cheek before she smooths down the flowered hem of her dress. How long had he stood there like a dummy, gazing into the empty stripe of sunlight?

On Mykonos scuffing his way through hot sand he’d seen naked bodies every size, shape and color stretched for acres between green sea and rocks spilled at the base of cliffs, bodies so casual, blasé, he ignored them, preferred them at night, clothed, in the restaurants and discos. Funny how quickly he’d gotten used to nakedness. Hair, skin, bones. What was different, what was the same about all the bodies. Blond, dark, lean, stubby, every nation represented, all shapes of male and female displayed in any angle he could imagine. What was he looking for in women’s bodies? Surely he’d have tripped over it trudging up and back those golden beaches on Mykonos. But no. The mystery persisted. His woman in the park. A daydream till she brushes bits of straw from the seat of her paisley dress. Runs away.

Rules posted in the park, but the signs, blasted by spray paint, unreadable. No rules, no signs when he’d lived here a decade ago. He’d remembered a green oasis. Forgotten those seasons, months when the park was the color of the neighborhood surrounding it. No color. Grays and browns of dead leaves. July now. Trees should be full, the grass green. He’d been hoping for green. Hoping the park sat green and waiting between Woodland and Baltimore avenues, that it had not been an invention, one more lie he’d told himself about this land to which he was returning.

A statue of Charles Dickens. Only one in the world at last count. Little Nell at his knee stares imploringly up at the great man’s distant face. They are separated and locked together by her gaze. Both figures larger than life, greener than the brittle grass. Both blind. In a notebook somewhere Cudjoe had recorded the inscription carved into the pedestal. For his story about people who frequent the park. A black boy who climbs on Dickens’s knee and daydreams. A crazy red-haired guy muttering and singing nonsense songs to himself. A blind man who shoots baskets at night. A boy-girl vignette about a baby the girl’s carrying, how the couple strolls round and round the path, kids on a carousel, teaching themselves the news of another, unexpected life.

Twenty blocks west the fire had burned. If the wind right, smoke would have drifted here, settled on leaves, grass, bushes. Things that eat leaves and buds must have tasted smoke. Dark clouds drifting this way carried the ashy taste of incinerated children’s flesh. Could you still smell it? Was the taste still part of what grew in the park? Would it ever go away?

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (October 6, 2020)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982148843

Raves and Reviews

"Daring and award-winning ... Wideman’s quasi-cubist approach to storytelling — full of angular sentence shards and deft rule-breaking — explores multiple facets of the tragedy and sometimes drags the reader and the author himself onto the page."

—Philadelphia Inquirer

"A passionate, angry and formally fascinating novel of urban disintegration."

—The New York Times Book Review

"A book brimming over with brutal, emotional honesty and moments of beautiful prose lyricism."

—Washington Post Book World

"A blaze of rage... Wideman's genius for impassioned imagery triumphs."

—Los Angeles Times Book Review

"Philadelphia Fire isn't a book you read so much as one you breathe."

—San Francisco Chronicle

"A pyrotechnic display... Wideman charges his sentence with energy that flares into beauty at unexpected moments... [His] work reflects extraordinary talent, will, and courage."

—Boston Globe

"Very few writers have Wideman's gifts and range. His artistic courage is rare these days."

—Philadelphia Inquirer

"Like the Russian master [Dostoyevsky], Wideman probes the torments of the soul... Powerful."

—U.S. News & World Report

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Philadelphia Fire Trade Paperback 9781982148843

- Author Photo (jpg): John Edgar Wideman ©Jean-Christian Bourcart(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit