How God Works

The Science Behind the Benefits of Religion

By David DeSteno

LIST PRICE $18.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

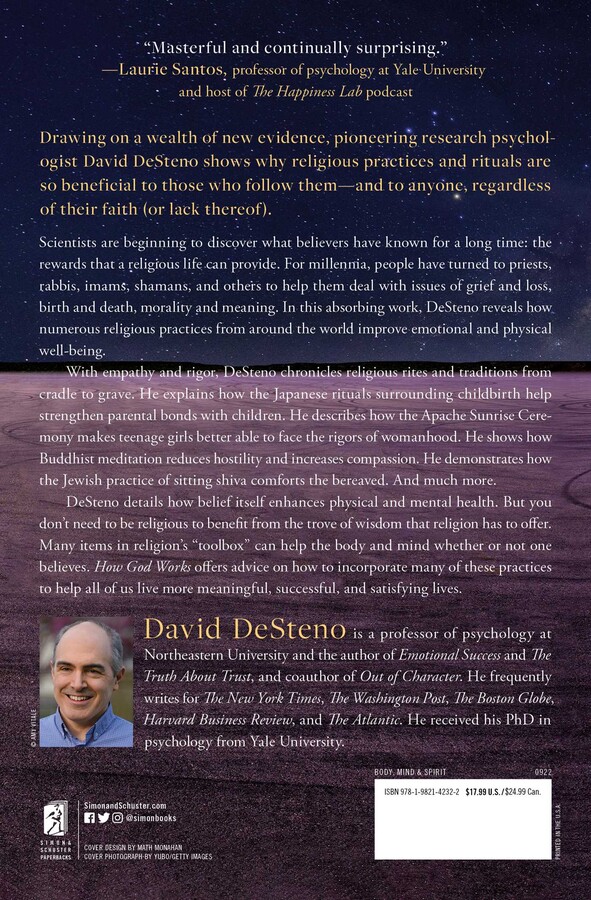

Drawing on a wealth of new evidence, pioneering research psychologist David DeSteno shows why religious practices and rituals are so beneficial to those who follow them—and to anyone, regardless of their faith (or lack thereof).

Scientists are beginning to discover what believers have known for a long time: the rewards that a religious life can provide. For millennia, people have turned to priests, rabbis, imams, shamans, and others to help them deal with issues of grief and loss, birth and death, morality and meaning. In this absorbing work, DeSteno reveals how numerous religious practices from around the world improve emotional and physical well-being.

With empathy and rigor, DeSteno chronicles religious rites and traditions from cradle to grave. He explains how the Japanese rituals surrounding childbirth help strengthen parental bonds with children. He describes how the Apache Sunrise Ceremony makes teenage girls better able to face the rigors of womanhood. He shows how Buddhist meditation reduces hostility and increases compassion. He demonstrates how the Jewish practice of sitting shiva comforts the bereaved. And much more.

DeSteno details how belief itself enhances physical and mental health. But you don’t need to be religious to benefit from the trove of wisdom that religion has to offer. Many items in religion’s “toolbox” can help the body and mind whether or not one believes. How God Works offers advice on how to incorporate many of these practices to help all of us live more meaningful, successful, and satisfying lives.

Scientists are beginning to discover what believers have known for a long time: the rewards that a religious life can provide. For millennia, people have turned to priests, rabbis, imams, shamans, and others to help them deal with issues of grief and loss, birth and death, morality and meaning. In this absorbing work, DeSteno reveals how numerous religious practices from around the world improve emotional and physical well-being.

With empathy and rigor, DeSteno chronicles religious rites and traditions from cradle to grave. He explains how the Japanese rituals surrounding childbirth help strengthen parental bonds with children. He describes how the Apache Sunrise Ceremony makes teenage girls better able to face the rigors of womanhood. He shows how Buddhist meditation reduces hostility and increases compassion. He demonstrates how the Jewish practice of sitting shiva comforts the bereaved. And much more.

DeSteno details how belief itself enhances physical and mental health. But you don’t need to be religious to benefit from the trove of wisdom that religion has to offer. Many items in religion’s “toolbox” can help the body and mind whether or not one believes. How God Works offers advice on how to incorporate many of these practices to help all of us live more meaningful, successful, and satisfying lives.

Excerpt

Chapter 1: Infancy: Welcoming and Binding Infancy: Welcoming and Binding

Allah is most great. I bear witness that there is none worthy of being worshipped except Allah. I bear witness that Muhammad is the apostle of Allah. Come to prayer. Come to success.

Whether in the hospital, or more traditionally surrounded by female family and friend attendants at home, these are the first words that a Muslim child hears moments after birth. As the infant is presented to its father for the first time, he cradles it adoringly and recites these words, which constitute part of the adhan, or Muslim call to prayer, into the child’s right ear.

A few moments afterward, another honored family member or friend rubs a small piece of softened date or other sweet treat on the infant’s upper palate—a ritual known as the tahneek. The symbolism of this action is twofold. Traditionally, the person offering the date had first softened it in their own mouth, so passing their saliva to the infant marked a hope that their noble traits would pass as well. The second symbolism of tahneek is the hope that the treat would bode good fortune for the child’s coming life—a life to be filled with sweet things.

As beautiful as birth is, it marks one of the biggest changes in life. For infants, it’s the start of a journey. For parents, it’s a reset of sorts—an event that will fundamentally change their routines and priorities. And while everyone involved wants this new life to be a success, that success is by no means guaranteed. It will require a mix of sacrifice and support to bring it to fruition.

Our success in the first few years of life boils down to gaining acceptance, both from our parents and by the larger web of people who surround us. The more practical and emotional sustenance our parents give us, the better off we’ll be throughout our lives. And the more favorably our community looks upon us, the better chance we’ll have for support in the short and long term.

Fortunately, we humans come equipped with tools for ingratiating ourselves to others right from the start. Hormonal responses, the specific sound of cries, and even babies’ physical appearances all help to elicit care from parents and welcoming smiles form passersby. Babies are cute for a reason. Their rounded features evoke an instinctual affection in most people—even strangers.

Biology isn’t destiny, though. Sometimes it goes wrong or just isn’t strong enough on its own to create and maintain the support growing babes need to thrive. Sometimes parents can face a lot of stress or anxiety that impedes their ability to connect with a new child. Sometimes they’re just burned out or not willing to give as much time, attention, or support to their child as they could. Sometimes, especially for someone who isn’t a parent, appreciating the specialness and potential of any infant can be difficult. They’re squishy, demanding blobs, after all.

Here’s where the spiritual technologies that surround birth come into play. Whichever faith they come from—Muslim, Christian, Shinto, or the like—they all serve one overarching goal: to boost any infant’s odds. Although the symbols and practices may differ a bit, these practices work to help parents provide the support their new young ones need and to help the community see why they should welcome these babies into their midst. As the Muslim adhan states explicitly: by coming to prayer and services—by adopting these technologies—people will be coming to success. That’s as true at the beginning of life as it is later on.

Tending Comes First

Shinto is the national religion of Japan, and most Japanese practice it to some extent. The word shinto means “the way of the gods,” and Shinto practice centers on belief in kami—spirits that inhabit natural places and living beings.

In Shinto, the birth of a child is a gift of the kami, and throughout the early years of its life, the rituals focus parents not only on caring for and celebrating their child but also on gratitude for their existence. The child is so prized that ritualized care for it starts well before its birth. During the fifth month of pregnancy, Japanese mothers-to-be celebrate the obiiwai—the ritual of sash binding. Here, a close female relative ties a beautiful cotton belt around the expectant mother’s belly to provide gentle support, warmth, and protection for the growing child it cradles. Often, obiiwai takes places in Shinto shrines but it can be performed in the home as well. The ritual also involves prayers for the coming child’s welfare. The sash itself also serves as a reminder of the responsibilities of motherhood. It marks the symbolic start of caretaking.

Assuming all goes well at birth, the next ritual Shinto prescribes is oshichiya, or the naming ceremony. On the seventh evening after a child is born, the parents invite family and friends to take part in a joyous meal, traditionally consisting of sea bream (a fish whose name in Japanese is a homonym of the word for joy) and rice with red beans. Up to now, the family may have been using a silly nickname to refer to the baby, but on this evening the parents formally announce the true name to everyone and begin to use it. To mark the specialness of the occasion and the pride they take in their new little one, who is traditionally dressed in white, they also ceremonially write the child’s name using calligraphy on special white paper that they then hang on the wall. This celebration formally begins the child’s introduction to the world beyond its home.

After a month, the family takes part in omiyamairi: the infant’s first visit to a Shinto shrine. Parents and babies dress their best for this, which for the baby means buying another new outfit and a special kimono to wrap it in. Traditionally, it’s the paternal grandmother who carries the child into the shrine, as Japanese custom suggests that mothers need to rest as much as possible after giving birth.

Once inside, the Shinto priest will wave an onusa—a stick with dozens of billowing papers attached to it—from side to side to purify everyone before using another sacred rod with bells attached to it to remove the influence of any evil spirits from the child. Throughout all of this, the priests also thank the kami for the child’s birth and beseech them to protect the child and give it good fortune. Omiyamari, like many Shinto rites around a child’s early years, also entails a significant cost for the parents. Besides the expense for the new clothes and kimono, the parents also are expected to make a sizable donation to the shrine and to provide commemorative gifts to everyone who attended.

Next, when the child is about four months old, the family celebrates okuizome: the first bite of food. Since it’s not a great idea to feed adult food to kids that age, the meal is largely symbolic. The parents first purchase an expensive red (for boys) or black (for girls) set of dishware and then prepare a traditional Japanese meal, again consisting of sea bream, red beans and rice, but also pickled vegetables and soup. Small bits are then pretend-fed to the child while the larger family enjoys the banquet in earnest.

When the first March 3 for girls or May 5 for boys rolls around, it’s time for hatsuzekku. As with the earlier rituals, the focus here is on celebrating the child and expressing gratitude that he or she has, hopefully, been growing in size and strength. Girls receive hina—ornamental dolls representing the royal family and court. For boys, the home is decorated with samurai figures and armor. Here, too, the larger family often gathers for celebratory meals provided by the young one’s parents.

When it’s time for a child’s first birthday, there’s yet another ritual celebration. Here, parents put sticky rice patties, a sacred Shinto food, in a pouch on the baby’s back while the child tries to walk with the added weight. The goal isn’t to weigh them down but to transfer power to them.

No matter how you count it, that’s a very busy first year! But it’s not where Shinto’s ritual celebrations of children ends. At three, five, and seven years of age, shichigosan is celebrated—a ritual in which children are again dressed in traditional clothes and taken to shrines for prayers and blessings that express appreciation for their development and ask for continued good fortune. With each, parents again face costs in terms of time and money. There are new clothes to buy, donations to make, and meals to provide for family and friends.

Almost all of the world’s religions include rituals similar to Shinto’s oshichiya and omiyamairi. For Hindus, the name-giving ceremony known as namakarana usually occurs around the twelfth day after birth and centers on family and friends gathering while a parent, led by a priest, writes the child’s name on a piece of paper (to be sanctified by the priest) and then whispers it into the child’s ear before announcing it to all. In Islam, the naming ceremony known as the aqiqah takes place a week after the child’s birth. Christians baptize their babies. That ceremony doesn’t reveal the child’s name per se, but the priest does highlight the name while blessing the new arrival with holy water. Jews hold a brief ceremony in which an infant’s Hebrew name is announced to the congregation at temple.

This convergence of rites for naming and blessing across religions anticipates a truth more recently discovered by psychologists and other scientists. We don’t name what we don’t value, and giving something or someone a name confers value upon it. At the most basic psychological level, a specific name, as opposed to a generic label like “baby,” implies that something has a mind; it has agency. And whatever has agency—whatever can think and feel—is worthy of our concern. Its joys and its pains matter, even if it doesn’t yet have the ability to express them.

Just giving or recognizing that something has a name makes us feel more empathetic toward it. Pets are a great example, but it even works for mundane, mindless objects. Your car, your computer, even a cucumber. Research has shown that many people’s brains respond differently to the piercing of a vegetable that has been given a human name. Via brain imaging, we can see that people show greater signs of empathic distress when vegetables that have been named Bob or Sue get pricked with a needle compared to when their unnamed counterparts get stuck on the cutting board.

A name serves not only as a form of identification, but as a marker of moral worth. And giving or announcing a name as part of a ritual stands as a public way of reinforcing that value. It’s an additional reminder to people, especially those beyond the immediate family, that a baby—a wriggly lump of flesh who can’t even look anyone in the eye—is nonetheless a being capable of feeling who deserves the community’s respect and protection. It’s also why many faiths encourage parents to name their children after saints, respected family members, and the like. Those names are associated with virtues—virtues that come to mind and color impressions of the seeming blank slates that infants present.

You can also see the psychological power of naming in another way: its reverse. The process of dehumanization often begins by refusing to call people by their names. Referring to people by a number, or calling them pigs or dogs, is a first step many regimes have used to enable later cruelty. When you remove people’s names, you automatically inhibit the normal empathy we’d feel for them. This is also why we don’t name the animals we intend to eat.

The rites of Shinto, though, go much beyond naming rituals. And while it’s not the only religion that has some additional rites surrounding the early years of a child’s life, the front-loaded package it offers is exceptional in the ways it focuses parents on tending to and embracing the value of their children in a very costly public way.

Since a child depends on its parents for everything, quickly developing a strong bond between the two is an essential ingredient for their health and well-being, both in the moment and in the long run. Children who grow up without strong and nurturing relationships with their parents have trouble forming friendships and romantic relationships, and they’re more susceptible to depression, anxiety, and related illness later in life. Put simply, not receiving consistent parental care and warmth sets a child up for failure. For this reason, our bodies come equipped with a suite of tools meant to help us rapidly form deep attachments with infants.

During birth and the months that follow, hormones flood a mother’s brain to help ensure that this needy, crying, helpless human evokes love rather than ire or indifference. Fathers, too, get a hormone boost: their levels of oxytocin, which is central to forming bonds, rise when they hold or play with their child. But, for some parents—20 percent to 30 percent, depending on the survey—the hormonal boost just isn’t enough to make the love flow. Try as they might, they can’t connect with their baby. And even for the 80 percent who can connect, maintaining their devotion during sleepless nights, constant cleanup, and the many other trials of new parenthood can often be a challenge. Yet, as Alison Gopnik, one of the world’s leading experts on child development, has said, “We don’t care for children because we love them; we love them because we care for them.”

I realize this sounds kind of backward. And I’m not saying that the only reason we love our children is because we go through the motions of care. But for those times when biology isn’t enough, it’s good to have a backup. And that’s exactly what many religious rituals surrounding children’s early years provide. They make parents provide care, often in very public ways, and in so doing, they psychologically nudge parents’ minds toward increased feelings of commitment to their children.

It might seem strange to say that parents need help staying committed to their children, but it makes sense. The parent-infant relationship is among the most one-sided of all human bonds. Parents must make huge sacrifices of time, money, and energy for little or no short-term gain. From the parents’ point of view, it’s all give and no take. For them, the benefits—having someone to help and support you emotionally, physically, and financially—only start accruing years later. In most areas of life, we humans prefer immediate satisfaction over delayed rewards, even when those delayed benefits are bigger. It’s one reason so many of us spend more than we save, eat more than we should, or seek out other pleasures that can only harm us in the long term (e.g., any drug from nicotine to methamphetamine). When it comes to babies, we’re built to get pleasure from coos, smiles, and snuggles as a way to offset these short-term costs. But sometimes those fleeting pleasures aren’t enough.

Fortunately, the brain has a mental glitch of sorts that works to combat our desire for immediate pleasure. Psychologists call it the sunk cost fallacy. It’s the idea that after having put money or other resources toward a goal, people become more likely to stick with that goal even if, objectively speaking, it no longer seems to be the most desirable option. It’s why people who have paid to take a class or pursue a degree keep paying more to finish the program even if they don’t like it. It’s also why gamblers so frequently throw good money after bad. They feel their previous costs would be wasted if they stopped. But it’s often more logical to cut your losses than to keep spending to justify what you started.

It’s a bias that affects social relationships too. People often stay in poor ones because they feel they have already invested so much time and effort that it would be a shame to leave. So in many cases the sunk cost fallacy leads to irrational behavior.

Children aren’t exactly a sunk cost. But, as I noted, the benefits they offer lag far behind the costs to time, energy, and money that parents incur. As a result, those expenditures—the ones made during the preceding days, weeks, and even years before children can “pay back”—can feel like sunk costs. If you’re a parent, you may not think your mind is keeping track of these sacrifices, but it is subconsciously.

The good news is that, when it comes to children, this mental glitch can actually be an advantage. Your mind’s resistance to forfeiting sunk costs counteracts its desire for immediate gratification. And in cases where the rewards for sacrifice are real but delayed—cases like parenting—that can be quite helpful and rational.

Rituals reinforce this advantage in three ways. The first is by increasing the feelings of sunk costs. Spending time, money, and effort to organize and host several ceremonies along with the gifts and other accessories they entail amounts to a sizable cost. Secondly, ceremonies enhance memory. Your brain will only use feelings of sunk costs to increase commitment to the extent that it encodes and remembers them. And while memories of the caretaking behaviors of the daily grind might grow dim, memories of major celebrations won’t. The third and most important way rituals reinforce commitment is through their very public nature. Decades of psychological research show that we all cling harder to views and behaviors that we publicly announce or demonstrate. By taking part in several Shinto ceremonies designed to honor their children, Japanese parents publicly affirm and reinforce their devotion time and again. With each iteration, their minds’ desire for consistency between acts and beliefs nudges those beliefs about their children’s value to greater heights.

There’s evidence to support this thesis that the repeated Shinto rituals we’ve seen here strengthen the bonds between parents and children. On average, the bond between Japanese mothers and their children is one of the most empathic and intimate of any culture. Note that I’m focusing on the mother-infant bond here, as across most cultures mothers tend to be the primary caretakers of children. This is especially evident in Japan, a country with one of the most gender-biased work cultures in the world. By custom, Japanese men are devoted to their employers. For most, this results in long hours spent away from the home. This gender bias can certainly cause much unfair stress for many Japanese mothers, who could otherwise pursue their careers as well.

Still, when it comes to the mother-infant bond, Japanese mothers do everything they can to deepen it, even when controlling for their levels of available time. For example, they choose to spend more time near their children, engage in greater co-sleeping (this statistic includes fathers as well), have more skin-to-skin contact through play and bathing (again, this applies to Japanese fathers too), speak in warmer and more emotionally laden tones, and generally share more activities with their children than do most people in other cultures. These behaviors forge very deep bonds between mother and child—so much so that Japanese children tend to show less demanding and defiant behaviors when spending time with their moms than do children of many other nationalities.

In fact, the bond between Japanese mother and child is so strong and central to the culture that it produces a rather distinct emotion known as amae. Although the word amae has no direct translation into English, it can be described as a sense of intense closeness between mother and child—one where the child is feeling loved and cared for and the mother is enjoying cherishing her child. As an example, amae is the feeling that emerges when a young child climbs up on the lap of their busy mother, asking her to read a story, and she lovingly assents. It’s that cherishing feeling that leads her to enjoy putting her child’s needs first. Here, the child feels a comforting sense of being taken care of, and the mother feels a warm sense of being needed and trusted. That complex bundle of emotions—experienced in many different situations—is amae.

You don’t have to be Japanese to feel amae; most parents have experienced something similar at times while raising their children. But the reason amae doesn’t have a matching counterpart in English or many other languages is because it’s not as common an experience as it is in Japan. Cultures develop labels for the emotions that they experience most frequently. And while states like sadness and anger are fairly common across the globe, others, like amae, only occur with regularity in certain places.

There’s no way to prove conclusively that the Shinto rituals directly helped to create and reinforce Japanese parent-child bonds. To test this idea in a truly scientific way, we’d have to randomly select hundreds of nonreligious couples about to become pregnant, convert half of them to Shinto, ensure they perform these rituals, and then examine and compare the bonds they have with their children over the next seven years. For obvious ethical and practical reasons, that’s an impossible experiment to carry out.

Still, I believe these rituals do play a central role in strengthening bonds. If I brought parents to my lab and had them repeatedly spend time and money to celebrate their child, I’d fully expect, based on a large body of scientific work, that their feelings and behaviors toward them would become even more positive afterward. From everything scientists know, these types of behaviors increase feelings of commitment and attachment.

Conducting these rituals not in a lab but in a more meaningful and public way that evokes even stronger emotions can only amplify the effects the rituals have on parental care and devotion, one that accumulates over time—a snowball effect. How parents feel and act toward their children on one day builds on all the feelings and actions that preceded that day. The more they act in ways that show care and devotion to their child, the more committed they become to keep doing so. And the more they remember such acts, spend time and money on them, and reflect on them, the better. There will always be bumps—events that can stress these bonds—but here again is why a series of rituals can help ensure parents don’t metaphorically throw in the towel. You can think of these as booster shots for devotion. They can even leverage biology. As they nudge parents to increase or at least maintain caretaking, those actions in turn release more oxytocin to help cement the bonding.

You can already see some evidence for this idea—that simply acting out caring behaviors can create feelings of love—intuited in the recommendations that many physicians and parenting organizations offer to help people bond with their babies. Most recommend performing rituals (their word, not mine) that include regular times to massage the baby, to read them a story, to rock them while humming or singing. A time when the baby is the only focus. Such rituals, for all the reasons we’ve just seen, will further convince the mind that love for a child should and must be there, and, as a result, love will grow.

From the naming ceremony onward (or even before birth, as in Shinto), religious rituals offer tools to do just this. But you don’t have to be a person of faith to benefit. In fact, if you go back and look at many of the Shinto practices I described, most aren’t deeply religious in nature. Shinto prayers play only a small part. The main activities of almost all the ceremonies could be done in a completely secular way. What matters most in all cases is the ritualized repetition of the acts that makes them feel more special, meaningful, and public than eating a simple meal or giving a simple gift. By holding several ceremonies for your child during the first years of life, when their ability to give back is limited—maybe by adding quarter- or half-birthday celebrations, or celebrations with extended family focused on honoring different milestones in your child’s development during the first years—you will deepen your feelings of connection. Even setting aside special times every day for activities that show devotion to a child—reading to, massaging, or playing a game—can help increase love and patience for them. Those feelings will prod you to keep the bonds between you strong and support you during the challenges that will invariably arise.

Parting the Clouds

In virtually every society, mothers bear the brunt of the challenges child-rearing entails. For this reason, many faiths have long recognized the need to give new mothers some sort of respite. In the month or two after birth, many religions have rituals and practices that relieve mothers of some or most of their new responsibilities. For example, Muslim mothers are encouraged to rest for up to forty days, during which they’re exempted from many responsibilities. They don’t need to complete certain prayers or religious obligations. Other people help with household chores. The I Ching, China’s earliest book of divination, dictates that women should practice zuo yue zi, or “taking the month” as it’s now colloquially called, to rest, eat, and sleep, without being disturbed by the normal intrusions of daily life. Hindu tradition, guided by Ayurvedic medical knowledge, also advocates that mothers spend a month or so being attended to by family so that they can rest and bond with their newborns, often with both benefiting from daily ritualistic massage.

Although these practices might simply seem like well-deserved pampering, they’re an important backstop of sorts. As joyous as it can be to welcome a new child, it’s also very stressful. Sleep and work routines change. Responsibilities intensify. And a crying infant regularly makes its needs known. For many, this stress is temporary; any uptick in anxiety or “baby blues” quickly dissipates. But for some mothers, those baby blues mark the start of a dangerous downward spiral to depression. And women who have suffered from depression earlier in life are at an even greater risk of experiencing it again during or after pregnancy.

On average, about 12 percent of new mothers will develop postpartum depression (PPD)—a figure that rises to 17 percent if we include cases where the depression began during pregnancy rather than after birth. Fathers, too, can experience depression following the birth of a child; the best estimates suggest that about 8 percent do.

For mothers, three broad factors tend to predict whether PPD develops. The first is how much anxiety a mother feels during her pregnancy, with chronic worry making PPD more likely. The second is a lack of social support. As you might imagine, the more support a new mother has in the period following birth, the more protected she will be against PPD. The third is stress. Living a more stressful life, whether due to uncertainties about economic or physical safety, increases the likelihood that a new mom will develop PPD.

The potential damage of PPD isn’t limited to the mother. Its severity is linked to poorer outcomes for children, too, both immediate ones, including impaired bonding with parents, and long-term ones, such as increased behavioral problems and reduced cognitive abilities. As a result, PPD is particularly pernicious. It can lead mothers to feel guiltier because of the effect that PPD has on their children—and this guilt often intensifies depression.

Because of the threat posed by PPD, several faith traditions have developed tools to support new mothers. Through practices like zuo yue zi and, as we’ll soon see, prayers of acceptance, religions have found ways to reduce anxiety and stress to combat PPD.

In the case of zuo yue zi and related traditions, it’s important to recognize that how well these rituals work does depend on a few factors. Unlike the rituals that celebrate a baby’s arrival—rituals that everyone looks upon with joy—these postpartum practices can be double-edged swords. It all depends on context. Anthropologists bundle all these rituals under the label “postpartum confinement.” Almost all involve removing new mothers from their normal routines, usually by separating them from men or visitors in order to be cared for in relative privacy by their own mothers, mothers-in-law, or other female relatives. But whether such confinement feels like a luxury or a prison can vary.

Not every new mother relishes this change. And during the past several decades, with many societies across the globe in rapid economic and social transition, traditional roles are being upended at a faster rate, making it even more likely that many women might not see a value in adhering to these traditional rituals. Even though they may ultimately accept the practice due to family pressure, they might well feel that taking a monthlong respite would adversely affect their professional or social lives.

If, however, a new mother would like the respite and feels comfortable with those providing it, these rituals can offer a sizable psychological benefit. For example, in one study of 186 Taiwanese women, those who freely chose to follow the ritual practice of “doing the month” suffered from significantly fewer depressive symptoms. Similar findings come from a study on postpregnancy well-being among women in Hong Kong.

Religions have other ways to build support besides isolation periods. Just taking part in the regular activities of faith can be a great help. In fact, participating in religious activities even a few times per month decreases the likelihood of postpartum depression by more than 80 percent. It’s well-known that getting support from a community of friends—help with chores, times to laugh or bond in a safe environment—protects against PPD. What’s fascinating, though, is that being more religiously active increases this type of support for parents.

One way to see this comes from the puzzling finding that among religious families increasing numbers of children don’t correspond to less quality time being spent with them or poorer long-term outcomes (e.g., education, wealth, health). Usually, as the number of children in a family grows, each child gets fewer resources. But this doesn’t hold among those who are very religious, at least when compared to those who are completely secular.

One reason why is alloparenting. In the strictest sense, “alloparenting” means giving care to a child much as a parent would even though those children aren’t direct descendants. So, if an aunt or a friend provides care for a child that usually falls to a mother or father, that aunt or friend is acting as an alloparent. And, of course, the more alloparenting that goes on in any one family, the more time the parents have to devote energy and resources toward things that benefit each of their children—more time to teach or care for them individually, or even to attend to other responsibilities that improve the family’s, and thus each child’s, opportunities.

In 2020, a groundbreaking study of over twelve thousand people confirmed that religious people are more likely to have a child than are those who identify as secular. More notably, it showed that as parents’ involvement with their religion increases, so, too, does their ability to successfully raise more children. A central reason why was that stronger faith and stronger participation also increased the amount of alloparenting from community members who didn’t have children of their own. By so doing, community members not only help parents increase the time and resources they can give to each of their children, they also help reduce the stress, anxiety, and guilt often felt by parents who are pushed to the limit.

As important as community support is for a new parent’s well-being, belief can play a role as well. Since the brain is a prediction machine, it’s always running simulations—what-ifs, if you will—as a way to help us prepare for what might be coming down the pike. When it comes to pregnancy and new children, those what-ifs can feel especially urgent: What if the baby isn’t healthy? What if there’s not enough money to take care of it? What if…? You get the picture. Since heightened anxiety can make it more likely that women will have to deal with PPD or related types of psychological distress, anything that calms worry should help. And here’s where a belief in God comes in.

The psychologist Andrea Clements has long studied religious surrender, which she defines as an active, intentional subordination of one’s hopes and actions to God’s will. This doesn’t mean living in passive ignorance, simply expecting God to assist or punish you as It sees fit. But it does mean accepting that not everything is under your control and taking comfort in the fact that greater forces are shaping your destiny.

As Clements has found, religious surrender is an effective buffer against stress and anxiety. Those who accept this notion are calmer than the rest of us, both generally and in the face of specific anxiety-provoking events—like the ones that often occur around a baby’s birth. Pregnant women who embrace a greater surrender as part of their religious beliefs and prayers experience less worry and stress during this time as well as lower rates of PPD at six months after their children are born. Similarly, women who report finding greater strength, comfort, and peace from their faith and prayers—a notion closely aligned with religious surrender—also experience PPD at much lower rates months after giving birth.

The upshot here is clear. Belief soothes worry. Avoiding the impulse to assess every possible outcome—many of which we can’t control—eases stress, making us calmer and healthier.

These rituals suggest that whether or not we belong to a particular faith, we can make use of the tools faith has devised to handle what is arguably the greatest transition—birth—for both parents and newborns. Perhaps the easiest to apply outside of any particular religious tradition is isolating the new mother—as long as she welcomes the isolation and the people who will be helping her acclimate to the challenges of her new role. Many families already do something along these lines by having a dear relative or friend visit the family in the days or weeks after the new baby arrives.

I’d urge the families of any parent-to-be to find out what they need and to make time for them to rest and feel supported. It needn’t be 24/7, although the more time, the better. What is essential, though, is doing it in a way that’s special, preplanned, and orderly. I’m talking about a sort of care that’s more formal than a friend dropping off supplies or stopping by to visit the parents for an hour. There’s nothing wrong with such casual assistance, but it lacks the power that a more structured approach gives the new parents. The latter reduces their anxiety by bolstering their confidence in a network of friends and family whom they can always count on.

Belief in a deity also reduces anxiety, but even nonbelievers can access some of the benefits of psychological surrender we saw earlier. This may well be a trickier process in cognitive terms than establishing a support network, but it’s possible. One needn’t be a Buddhist to see the wisdom of the eighth-century Buddhist teacher Shantideva: “If a problem can be solved, what reason is there to be upset? If there is no possible solution, what use is there being sad?” Again, it may be tricky to adopt such a Zen stance right away, but its logic is undeniable and worth embracing. The idea is that surrender or acceptance can be given not only to God but also to fate or the inscrutable mechanisms of an extremely complicated universe. That probably won’t make it any easier to deal with tragedy or misfortune if they do come, but it will free worrying minds from running every possible scenario beforehand and the stress that mindset always brings. Mindfulness means living in the present moment while not clinging to, yearning for, or dreading possibilities that may or may not ever come.

As we’ve seen, then, the primary challenge for children during the first few years of life is ensuring they get the care from family that they need to survive. This requires strengthening not only the commitment of their parents but also their parents’ well-being. It’s hard to care for someone if you’re feeling distressed yourself.

Once children reach school age, though, their success will begin to depend more on others. How they behave will start to drive how the community views them. And with that change comes the possibility that selfish or unethical behaviors can harm their standing in the community—a harm that often has lasting effects. We humans are built to be social. We need the cooperation and company of others to thrive. Virtually all faiths take this into account by wielding spiritual technologies that build children’s character and make them good citizens of their community, as we’ll see in the next chapter.

Allah is most great. I bear witness that there is none worthy of being worshipped except Allah. I bear witness that Muhammad is the apostle of Allah. Come to prayer. Come to success.

Whether in the hospital, or more traditionally surrounded by female family and friend attendants at home, these are the first words that a Muslim child hears moments after birth. As the infant is presented to its father for the first time, he cradles it adoringly and recites these words, which constitute part of the adhan, or Muslim call to prayer, into the child’s right ear.

A few moments afterward, another honored family member or friend rubs a small piece of softened date or other sweet treat on the infant’s upper palate—a ritual known as the tahneek. The symbolism of this action is twofold. Traditionally, the person offering the date had first softened it in their own mouth, so passing their saliva to the infant marked a hope that their noble traits would pass as well. The second symbolism of tahneek is the hope that the treat would bode good fortune for the child’s coming life—a life to be filled with sweet things.

As beautiful as birth is, it marks one of the biggest changes in life. For infants, it’s the start of a journey. For parents, it’s a reset of sorts—an event that will fundamentally change their routines and priorities. And while everyone involved wants this new life to be a success, that success is by no means guaranteed. It will require a mix of sacrifice and support to bring it to fruition.

Our success in the first few years of life boils down to gaining acceptance, both from our parents and by the larger web of people who surround us. The more practical and emotional sustenance our parents give us, the better off we’ll be throughout our lives. And the more favorably our community looks upon us, the better chance we’ll have for support in the short and long term.

Fortunately, we humans come equipped with tools for ingratiating ourselves to others right from the start. Hormonal responses, the specific sound of cries, and even babies’ physical appearances all help to elicit care from parents and welcoming smiles form passersby. Babies are cute for a reason. Their rounded features evoke an instinctual affection in most people—even strangers.

Biology isn’t destiny, though. Sometimes it goes wrong or just isn’t strong enough on its own to create and maintain the support growing babes need to thrive. Sometimes parents can face a lot of stress or anxiety that impedes their ability to connect with a new child. Sometimes they’re just burned out or not willing to give as much time, attention, or support to their child as they could. Sometimes, especially for someone who isn’t a parent, appreciating the specialness and potential of any infant can be difficult. They’re squishy, demanding blobs, after all.

Here’s where the spiritual technologies that surround birth come into play. Whichever faith they come from—Muslim, Christian, Shinto, or the like—they all serve one overarching goal: to boost any infant’s odds. Although the symbols and practices may differ a bit, these practices work to help parents provide the support their new young ones need and to help the community see why they should welcome these babies into their midst. As the Muslim adhan states explicitly: by coming to prayer and services—by adopting these technologies—people will be coming to success. That’s as true at the beginning of life as it is later on.

Tending Comes First

Shinto is the national religion of Japan, and most Japanese practice it to some extent. The word shinto means “the way of the gods,” and Shinto practice centers on belief in kami—spirits that inhabit natural places and living beings.

In Shinto, the birth of a child is a gift of the kami, and throughout the early years of its life, the rituals focus parents not only on caring for and celebrating their child but also on gratitude for their existence. The child is so prized that ritualized care for it starts well before its birth. During the fifth month of pregnancy, Japanese mothers-to-be celebrate the obiiwai—the ritual of sash binding. Here, a close female relative ties a beautiful cotton belt around the expectant mother’s belly to provide gentle support, warmth, and protection for the growing child it cradles. Often, obiiwai takes places in Shinto shrines but it can be performed in the home as well. The ritual also involves prayers for the coming child’s welfare. The sash itself also serves as a reminder of the responsibilities of motherhood. It marks the symbolic start of caretaking.

Assuming all goes well at birth, the next ritual Shinto prescribes is oshichiya, or the naming ceremony. On the seventh evening after a child is born, the parents invite family and friends to take part in a joyous meal, traditionally consisting of sea bream (a fish whose name in Japanese is a homonym of the word for joy) and rice with red beans. Up to now, the family may have been using a silly nickname to refer to the baby, but on this evening the parents formally announce the true name to everyone and begin to use it. To mark the specialness of the occasion and the pride they take in their new little one, who is traditionally dressed in white, they also ceremonially write the child’s name using calligraphy on special white paper that they then hang on the wall. This celebration formally begins the child’s introduction to the world beyond its home.

After a month, the family takes part in omiyamairi: the infant’s first visit to a Shinto shrine. Parents and babies dress their best for this, which for the baby means buying another new outfit and a special kimono to wrap it in. Traditionally, it’s the paternal grandmother who carries the child into the shrine, as Japanese custom suggests that mothers need to rest as much as possible after giving birth.

Once inside, the Shinto priest will wave an onusa—a stick with dozens of billowing papers attached to it—from side to side to purify everyone before using another sacred rod with bells attached to it to remove the influence of any evil spirits from the child. Throughout all of this, the priests also thank the kami for the child’s birth and beseech them to protect the child and give it good fortune. Omiyamari, like many Shinto rites around a child’s early years, also entails a significant cost for the parents. Besides the expense for the new clothes and kimono, the parents also are expected to make a sizable donation to the shrine and to provide commemorative gifts to everyone who attended.

Next, when the child is about four months old, the family celebrates okuizome: the first bite of food. Since it’s not a great idea to feed adult food to kids that age, the meal is largely symbolic. The parents first purchase an expensive red (for boys) or black (for girls) set of dishware and then prepare a traditional Japanese meal, again consisting of sea bream, red beans and rice, but also pickled vegetables and soup. Small bits are then pretend-fed to the child while the larger family enjoys the banquet in earnest.

When the first March 3 for girls or May 5 for boys rolls around, it’s time for hatsuzekku. As with the earlier rituals, the focus here is on celebrating the child and expressing gratitude that he or she has, hopefully, been growing in size and strength. Girls receive hina—ornamental dolls representing the royal family and court. For boys, the home is decorated with samurai figures and armor. Here, too, the larger family often gathers for celebratory meals provided by the young one’s parents.

When it’s time for a child’s first birthday, there’s yet another ritual celebration. Here, parents put sticky rice patties, a sacred Shinto food, in a pouch on the baby’s back while the child tries to walk with the added weight. The goal isn’t to weigh them down but to transfer power to them.

No matter how you count it, that’s a very busy first year! But it’s not where Shinto’s ritual celebrations of children ends. At three, five, and seven years of age, shichigosan is celebrated—a ritual in which children are again dressed in traditional clothes and taken to shrines for prayers and blessings that express appreciation for their development and ask for continued good fortune. With each, parents again face costs in terms of time and money. There are new clothes to buy, donations to make, and meals to provide for family and friends.

Almost all of the world’s religions include rituals similar to Shinto’s oshichiya and omiyamairi. For Hindus, the name-giving ceremony known as namakarana usually occurs around the twelfth day after birth and centers on family and friends gathering while a parent, led by a priest, writes the child’s name on a piece of paper (to be sanctified by the priest) and then whispers it into the child’s ear before announcing it to all. In Islam, the naming ceremony known as the aqiqah takes place a week after the child’s birth. Christians baptize their babies. That ceremony doesn’t reveal the child’s name per se, but the priest does highlight the name while blessing the new arrival with holy water. Jews hold a brief ceremony in which an infant’s Hebrew name is announced to the congregation at temple.

This convergence of rites for naming and blessing across religions anticipates a truth more recently discovered by psychologists and other scientists. We don’t name what we don’t value, and giving something or someone a name confers value upon it. At the most basic psychological level, a specific name, as opposed to a generic label like “baby,” implies that something has a mind; it has agency. And whatever has agency—whatever can think and feel—is worthy of our concern. Its joys and its pains matter, even if it doesn’t yet have the ability to express them.

Just giving or recognizing that something has a name makes us feel more empathetic toward it. Pets are a great example, but it even works for mundane, mindless objects. Your car, your computer, even a cucumber. Research has shown that many people’s brains respond differently to the piercing of a vegetable that has been given a human name. Via brain imaging, we can see that people show greater signs of empathic distress when vegetables that have been named Bob or Sue get pricked with a needle compared to when their unnamed counterparts get stuck on the cutting board.

A name serves not only as a form of identification, but as a marker of moral worth. And giving or announcing a name as part of a ritual stands as a public way of reinforcing that value. It’s an additional reminder to people, especially those beyond the immediate family, that a baby—a wriggly lump of flesh who can’t even look anyone in the eye—is nonetheless a being capable of feeling who deserves the community’s respect and protection. It’s also why many faiths encourage parents to name their children after saints, respected family members, and the like. Those names are associated with virtues—virtues that come to mind and color impressions of the seeming blank slates that infants present.

You can also see the psychological power of naming in another way: its reverse. The process of dehumanization often begins by refusing to call people by their names. Referring to people by a number, or calling them pigs or dogs, is a first step many regimes have used to enable later cruelty. When you remove people’s names, you automatically inhibit the normal empathy we’d feel for them. This is also why we don’t name the animals we intend to eat.

The rites of Shinto, though, go much beyond naming rituals. And while it’s not the only religion that has some additional rites surrounding the early years of a child’s life, the front-loaded package it offers is exceptional in the ways it focuses parents on tending to and embracing the value of their children in a very costly public way.

Since a child depends on its parents for everything, quickly developing a strong bond between the two is an essential ingredient for their health and well-being, both in the moment and in the long run. Children who grow up without strong and nurturing relationships with their parents have trouble forming friendships and romantic relationships, and they’re more susceptible to depression, anxiety, and related illness later in life. Put simply, not receiving consistent parental care and warmth sets a child up for failure. For this reason, our bodies come equipped with a suite of tools meant to help us rapidly form deep attachments with infants.

During birth and the months that follow, hormones flood a mother’s brain to help ensure that this needy, crying, helpless human evokes love rather than ire or indifference. Fathers, too, get a hormone boost: their levels of oxytocin, which is central to forming bonds, rise when they hold or play with their child. But, for some parents—20 percent to 30 percent, depending on the survey—the hormonal boost just isn’t enough to make the love flow. Try as they might, they can’t connect with their baby. And even for the 80 percent who can connect, maintaining their devotion during sleepless nights, constant cleanup, and the many other trials of new parenthood can often be a challenge. Yet, as Alison Gopnik, one of the world’s leading experts on child development, has said, “We don’t care for children because we love them; we love them because we care for them.”

I realize this sounds kind of backward. And I’m not saying that the only reason we love our children is because we go through the motions of care. But for those times when biology isn’t enough, it’s good to have a backup. And that’s exactly what many religious rituals surrounding children’s early years provide. They make parents provide care, often in very public ways, and in so doing, they psychologically nudge parents’ minds toward increased feelings of commitment to their children.

It might seem strange to say that parents need help staying committed to their children, but it makes sense. The parent-infant relationship is among the most one-sided of all human bonds. Parents must make huge sacrifices of time, money, and energy for little or no short-term gain. From the parents’ point of view, it’s all give and no take. For them, the benefits—having someone to help and support you emotionally, physically, and financially—only start accruing years later. In most areas of life, we humans prefer immediate satisfaction over delayed rewards, even when those delayed benefits are bigger. It’s one reason so many of us spend more than we save, eat more than we should, or seek out other pleasures that can only harm us in the long term (e.g., any drug from nicotine to methamphetamine). When it comes to babies, we’re built to get pleasure from coos, smiles, and snuggles as a way to offset these short-term costs. But sometimes those fleeting pleasures aren’t enough.

Fortunately, the brain has a mental glitch of sorts that works to combat our desire for immediate pleasure. Psychologists call it the sunk cost fallacy. It’s the idea that after having put money or other resources toward a goal, people become more likely to stick with that goal even if, objectively speaking, it no longer seems to be the most desirable option. It’s why people who have paid to take a class or pursue a degree keep paying more to finish the program even if they don’t like it. It’s also why gamblers so frequently throw good money after bad. They feel their previous costs would be wasted if they stopped. But it’s often more logical to cut your losses than to keep spending to justify what you started.

It’s a bias that affects social relationships too. People often stay in poor ones because they feel they have already invested so much time and effort that it would be a shame to leave. So in many cases the sunk cost fallacy leads to irrational behavior.

Children aren’t exactly a sunk cost. But, as I noted, the benefits they offer lag far behind the costs to time, energy, and money that parents incur. As a result, those expenditures—the ones made during the preceding days, weeks, and even years before children can “pay back”—can feel like sunk costs. If you’re a parent, you may not think your mind is keeping track of these sacrifices, but it is subconsciously.

The good news is that, when it comes to children, this mental glitch can actually be an advantage. Your mind’s resistance to forfeiting sunk costs counteracts its desire for immediate gratification. And in cases where the rewards for sacrifice are real but delayed—cases like parenting—that can be quite helpful and rational.

Rituals reinforce this advantage in three ways. The first is by increasing the feelings of sunk costs. Spending time, money, and effort to organize and host several ceremonies along with the gifts and other accessories they entail amounts to a sizable cost. Secondly, ceremonies enhance memory. Your brain will only use feelings of sunk costs to increase commitment to the extent that it encodes and remembers them. And while memories of the caretaking behaviors of the daily grind might grow dim, memories of major celebrations won’t. The third and most important way rituals reinforce commitment is through their very public nature. Decades of psychological research show that we all cling harder to views and behaviors that we publicly announce or demonstrate. By taking part in several Shinto ceremonies designed to honor their children, Japanese parents publicly affirm and reinforce their devotion time and again. With each iteration, their minds’ desire for consistency between acts and beliefs nudges those beliefs about their children’s value to greater heights.

There’s evidence to support this thesis that the repeated Shinto rituals we’ve seen here strengthen the bonds between parents and children. On average, the bond between Japanese mothers and their children is one of the most empathic and intimate of any culture. Note that I’m focusing on the mother-infant bond here, as across most cultures mothers tend to be the primary caretakers of children. This is especially evident in Japan, a country with one of the most gender-biased work cultures in the world. By custom, Japanese men are devoted to their employers. For most, this results in long hours spent away from the home. This gender bias can certainly cause much unfair stress for many Japanese mothers, who could otherwise pursue their careers as well.

Still, when it comes to the mother-infant bond, Japanese mothers do everything they can to deepen it, even when controlling for their levels of available time. For example, they choose to spend more time near their children, engage in greater co-sleeping (this statistic includes fathers as well), have more skin-to-skin contact through play and bathing (again, this applies to Japanese fathers too), speak in warmer and more emotionally laden tones, and generally share more activities with their children than do most people in other cultures. These behaviors forge very deep bonds between mother and child—so much so that Japanese children tend to show less demanding and defiant behaviors when spending time with their moms than do children of many other nationalities.

In fact, the bond between Japanese mother and child is so strong and central to the culture that it produces a rather distinct emotion known as amae. Although the word amae has no direct translation into English, it can be described as a sense of intense closeness between mother and child—one where the child is feeling loved and cared for and the mother is enjoying cherishing her child. As an example, amae is the feeling that emerges when a young child climbs up on the lap of their busy mother, asking her to read a story, and she lovingly assents. It’s that cherishing feeling that leads her to enjoy putting her child’s needs first. Here, the child feels a comforting sense of being taken care of, and the mother feels a warm sense of being needed and trusted. That complex bundle of emotions—experienced in many different situations—is amae.

You don’t have to be Japanese to feel amae; most parents have experienced something similar at times while raising their children. But the reason amae doesn’t have a matching counterpart in English or many other languages is because it’s not as common an experience as it is in Japan. Cultures develop labels for the emotions that they experience most frequently. And while states like sadness and anger are fairly common across the globe, others, like amae, only occur with regularity in certain places.

There’s no way to prove conclusively that the Shinto rituals directly helped to create and reinforce Japanese parent-child bonds. To test this idea in a truly scientific way, we’d have to randomly select hundreds of nonreligious couples about to become pregnant, convert half of them to Shinto, ensure they perform these rituals, and then examine and compare the bonds they have with their children over the next seven years. For obvious ethical and practical reasons, that’s an impossible experiment to carry out.

Still, I believe these rituals do play a central role in strengthening bonds. If I brought parents to my lab and had them repeatedly spend time and money to celebrate their child, I’d fully expect, based on a large body of scientific work, that their feelings and behaviors toward them would become even more positive afterward. From everything scientists know, these types of behaviors increase feelings of commitment and attachment.

Conducting these rituals not in a lab but in a more meaningful and public way that evokes even stronger emotions can only amplify the effects the rituals have on parental care and devotion, one that accumulates over time—a snowball effect. How parents feel and act toward their children on one day builds on all the feelings and actions that preceded that day. The more they act in ways that show care and devotion to their child, the more committed they become to keep doing so. And the more they remember such acts, spend time and money on them, and reflect on them, the better. There will always be bumps—events that can stress these bonds—but here again is why a series of rituals can help ensure parents don’t metaphorically throw in the towel. You can think of these as booster shots for devotion. They can even leverage biology. As they nudge parents to increase or at least maintain caretaking, those actions in turn release more oxytocin to help cement the bonding.

You can already see some evidence for this idea—that simply acting out caring behaviors can create feelings of love—intuited in the recommendations that many physicians and parenting organizations offer to help people bond with their babies. Most recommend performing rituals (their word, not mine) that include regular times to massage the baby, to read them a story, to rock them while humming or singing. A time when the baby is the only focus. Such rituals, for all the reasons we’ve just seen, will further convince the mind that love for a child should and must be there, and, as a result, love will grow.

From the naming ceremony onward (or even before birth, as in Shinto), religious rituals offer tools to do just this. But you don’t have to be a person of faith to benefit. In fact, if you go back and look at many of the Shinto practices I described, most aren’t deeply religious in nature. Shinto prayers play only a small part. The main activities of almost all the ceremonies could be done in a completely secular way. What matters most in all cases is the ritualized repetition of the acts that makes them feel more special, meaningful, and public than eating a simple meal or giving a simple gift. By holding several ceremonies for your child during the first years of life, when their ability to give back is limited—maybe by adding quarter- or half-birthday celebrations, or celebrations with extended family focused on honoring different milestones in your child’s development during the first years—you will deepen your feelings of connection. Even setting aside special times every day for activities that show devotion to a child—reading to, massaging, or playing a game—can help increase love and patience for them. Those feelings will prod you to keep the bonds between you strong and support you during the challenges that will invariably arise.

Parting the Clouds

In virtually every society, mothers bear the brunt of the challenges child-rearing entails. For this reason, many faiths have long recognized the need to give new mothers some sort of respite. In the month or two after birth, many religions have rituals and practices that relieve mothers of some or most of their new responsibilities. For example, Muslim mothers are encouraged to rest for up to forty days, during which they’re exempted from many responsibilities. They don’t need to complete certain prayers or religious obligations. Other people help with household chores. The I Ching, China’s earliest book of divination, dictates that women should practice zuo yue zi, or “taking the month” as it’s now colloquially called, to rest, eat, and sleep, without being disturbed by the normal intrusions of daily life. Hindu tradition, guided by Ayurvedic medical knowledge, also advocates that mothers spend a month or so being attended to by family so that they can rest and bond with their newborns, often with both benefiting from daily ritualistic massage.

Although these practices might simply seem like well-deserved pampering, they’re an important backstop of sorts. As joyous as it can be to welcome a new child, it’s also very stressful. Sleep and work routines change. Responsibilities intensify. And a crying infant regularly makes its needs known. For many, this stress is temporary; any uptick in anxiety or “baby blues” quickly dissipates. But for some mothers, those baby blues mark the start of a dangerous downward spiral to depression. And women who have suffered from depression earlier in life are at an even greater risk of experiencing it again during or after pregnancy.

On average, about 12 percent of new mothers will develop postpartum depression (PPD)—a figure that rises to 17 percent if we include cases where the depression began during pregnancy rather than after birth. Fathers, too, can experience depression following the birth of a child; the best estimates suggest that about 8 percent do.

For mothers, three broad factors tend to predict whether PPD develops. The first is how much anxiety a mother feels during her pregnancy, with chronic worry making PPD more likely. The second is a lack of social support. As you might imagine, the more support a new mother has in the period following birth, the more protected she will be against PPD. The third is stress. Living a more stressful life, whether due to uncertainties about economic or physical safety, increases the likelihood that a new mom will develop PPD.

The potential damage of PPD isn’t limited to the mother. Its severity is linked to poorer outcomes for children, too, both immediate ones, including impaired bonding with parents, and long-term ones, such as increased behavioral problems and reduced cognitive abilities. As a result, PPD is particularly pernicious. It can lead mothers to feel guiltier because of the effect that PPD has on their children—and this guilt often intensifies depression.

Because of the threat posed by PPD, several faith traditions have developed tools to support new mothers. Through practices like zuo yue zi and, as we’ll soon see, prayers of acceptance, religions have found ways to reduce anxiety and stress to combat PPD.

In the case of zuo yue zi and related traditions, it’s important to recognize that how well these rituals work does depend on a few factors. Unlike the rituals that celebrate a baby’s arrival—rituals that everyone looks upon with joy—these postpartum practices can be double-edged swords. It all depends on context. Anthropologists bundle all these rituals under the label “postpartum confinement.” Almost all involve removing new mothers from their normal routines, usually by separating them from men or visitors in order to be cared for in relative privacy by their own mothers, mothers-in-law, or other female relatives. But whether such confinement feels like a luxury or a prison can vary.

Not every new mother relishes this change. And during the past several decades, with many societies across the globe in rapid economic and social transition, traditional roles are being upended at a faster rate, making it even more likely that many women might not see a value in adhering to these traditional rituals. Even though they may ultimately accept the practice due to family pressure, they might well feel that taking a monthlong respite would adversely affect their professional or social lives.

If, however, a new mother would like the respite and feels comfortable with those providing it, these rituals can offer a sizable psychological benefit. For example, in one study of 186 Taiwanese women, those who freely chose to follow the ritual practice of “doing the month” suffered from significantly fewer depressive symptoms. Similar findings come from a study on postpregnancy well-being among women in Hong Kong.

Religions have other ways to build support besides isolation periods. Just taking part in the regular activities of faith can be a great help. In fact, participating in religious activities even a few times per month decreases the likelihood of postpartum depression by more than 80 percent. It’s well-known that getting support from a community of friends—help with chores, times to laugh or bond in a safe environment—protects against PPD. What’s fascinating, though, is that being more religiously active increases this type of support for parents.

One way to see this comes from the puzzling finding that among religious families increasing numbers of children don’t correspond to less quality time being spent with them or poorer long-term outcomes (e.g., education, wealth, health). Usually, as the number of children in a family grows, each child gets fewer resources. But this doesn’t hold among those who are very religious, at least when compared to those who are completely secular.

One reason why is alloparenting. In the strictest sense, “alloparenting” means giving care to a child much as a parent would even though those children aren’t direct descendants. So, if an aunt or a friend provides care for a child that usually falls to a mother or father, that aunt or friend is acting as an alloparent. And, of course, the more alloparenting that goes on in any one family, the more time the parents have to devote energy and resources toward things that benefit each of their children—more time to teach or care for them individually, or even to attend to other responsibilities that improve the family’s, and thus each child’s, opportunities.

In 2020, a groundbreaking study of over twelve thousand people confirmed that religious people are more likely to have a child than are those who identify as secular. More notably, it showed that as parents’ involvement with their religion increases, so, too, does their ability to successfully raise more children. A central reason why was that stronger faith and stronger participation also increased the amount of alloparenting from community members who didn’t have children of their own. By so doing, community members not only help parents increase the time and resources they can give to each of their children, they also help reduce the stress, anxiety, and guilt often felt by parents who are pushed to the limit.

As important as community support is for a new parent’s well-being, belief can play a role as well. Since the brain is a prediction machine, it’s always running simulations—what-ifs, if you will—as a way to help us prepare for what might be coming down the pike. When it comes to pregnancy and new children, those what-ifs can feel especially urgent: What if the baby isn’t healthy? What if there’s not enough money to take care of it? What if…? You get the picture. Since heightened anxiety can make it more likely that women will have to deal with PPD or related types of psychological distress, anything that calms worry should help. And here’s where a belief in God comes in.

The psychologist Andrea Clements has long studied religious surrender, which she defines as an active, intentional subordination of one’s hopes and actions to God’s will. This doesn’t mean living in passive ignorance, simply expecting God to assist or punish you as It sees fit. But it does mean accepting that not everything is under your control and taking comfort in the fact that greater forces are shaping your destiny.

As Clements has found, religious surrender is an effective buffer against stress and anxiety. Those who accept this notion are calmer than the rest of us, both generally and in the face of specific anxiety-provoking events—like the ones that often occur around a baby’s birth. Pregnant women who embrace a greater surrender as part of their religious beliefs and prayers experience less worry and stress during this time as well as lower rates of PPD at six months after their children are born. Similarly, women who report finding greater strength, comfort, and peace from their faith and prayers—a notion closely aligned with religious surrender—also experience PPD at much lower rates months after giving birth.

The upshot here is clear. Belief soothes worry. Avoiding the impulse to assess every possible outcome—many of which we can’t control—eases stress, making us calmer and healthier.

These rituals suggest that whether or not we belong to a particular faith, we can make use of the tools faith has devised to handle what is arguably the greatest transition—birth—for both parents and newborns. Perhaps the easiest to apply outside of any particular religious tradition is isolating the new mother—as long as she welcomes the isolation and the people who will be helping her acclimate to the challenges of her new role. Many families already do something along these lines by having a dear relative or friend visit the family in the days or weeks after the new baby arrives.

I’d urge the families of any parent-to-be to find out what they need and to make time for them to rest and feel supported. It needn’t be 24/7, although the more time, the better. What is essential, though, is doing it in a way that’s special, preplanned, and orderly. I’m talking about a sort of care that’s more formal than a friend dropping off supplies or stopping by to visit the parents for an hour. There’s nothing wrong with such casual assistance, but it lacks the power that a more structured approach gives the new parents. The latter reduces their anxiety by bolstering their confidence in a network of friends and family whom they can always count on.

Belief in a deity also reduces anxiety, but even nonbelievers can access some of the benefits of psychological surrender we saw earlier. This may well be a trickier process in cognitive terms than establishing a support network, but it’s possible. One needn’t be a Buddhist to see the wisdom of the eighth-century Buddhist teacher Shantideva: “If a problem can be solved, what reason is there to be upset? If there is no possible solution, what use is there being sad?” Again, it may be tricky to adopt such a Zen stance right away, but its logic is undeniable and worth embracing. The idea is that surrender or acceptance can be given not only to God but also to fate or the inscrutable mechanisms of an extremely complicated universe. That probably won’t make it any easier to deal with tragedy or misfortune if they do come, but it will free worrying minds from running every possible scenario beforehand and the stress that mindset always brings. Mindfulness means living in the present moment while not clinging to, yearning for, or dreading possibilities that may or may not ever come.

As we’ve seen, then, the primary challenge for children during the first few years of life is ensuring they get the care from family that they need to survive. This requires strengthening not only the commitment of their parents but also their parents’ well-being. It’s hard to care for someone if you’re feeling distressed yourself.

Once children reach school age, though, their success will begin to depend more on others. How they behave will start to drive how the community views them. And with that change comes the possibility that selfish or unethical behaviors can harm their standing in the community—a harm that often has lasting effects. We humans are built to be social. We need the cooperation and company of others to thrive. Virtually all faiths take this into account by wielding spiritual technologies that build children’s character and make them good citizens of their community, as we’ll see in the next chapter.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (September 6, 2022)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982142322

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): How God Works Trade Paperback 9781982142322

- Author Photo (jpg): David DeSteno Amy Vitale(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit