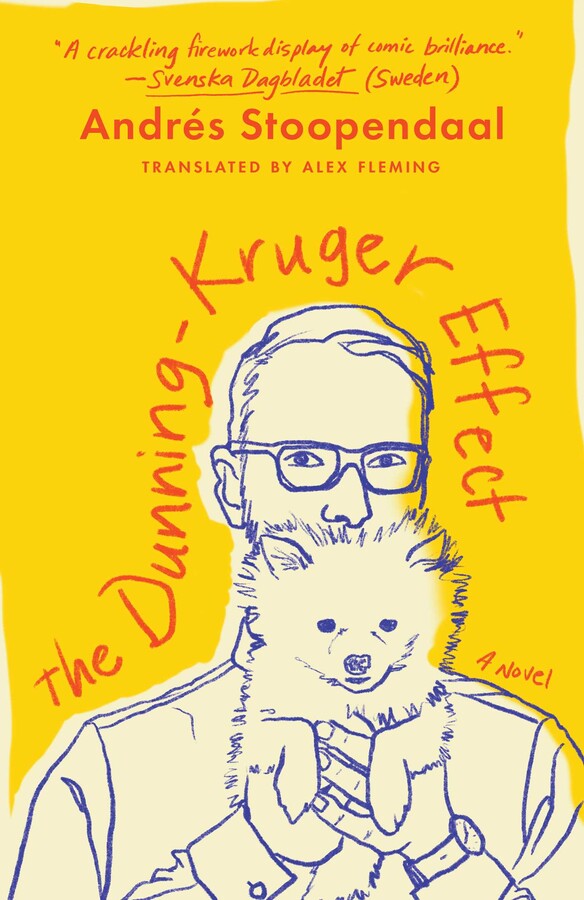

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

A Novel

LIST PRICE $27.99

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Convinced of his own moral and intellectual superiority, the nameless protagonist of this debut novel is also paralyzed by self-consciousness. Yet, inspired by Stephen King’s On Writing, he decides to dedicate four hours a day to work on his own novel over the course of one summer. Only, he must also balance his creative goals with a part-time government job and looking after his girlfriend’s possibly brain-damaged Pomeranian dog.

Too bad he’s uninspired by his job, almost kills the dog, and realizes his novel is slowly morphing into misguided fan fiction about French writer and enfant terrible Michel Houellebecq.

Even when he’s alone, he can’t help but pontificate before an imagined audience, making over-the-top cases for and against all manner of culture war battles and obsessing over identity politics. He’s an emblem of all the follies of our age—happily unaware that in his refusal to be ordinary, he’s become a walking cliché of misguided manhood.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a portrait of a person belatedly coming of age, a blistering takedown of a privileged man who believes he’s a revolutionary, and “a crackling firework display of comic brilliance” (Svenska Dagbladet, Sweden).

Excerpt

It was only in late March 2018, as fate would have it just weeks after the publication of Carl Cederström’s peculiar article in Svenska Dagbladet about Jordan B. Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos,I that I seriously came to understand what a truly incendiary, if not scandalous, figure the Canadian psychologist cut, among not only ordinary folk but also people in my own social circle.

My girlfriend, Maria, who was by this point fairly instrumental in managing my social life, and at whose place I was increasingly spending the night, had decided to invite her friend Agnes, a PhD student in art history, and Agnes’s partner, Otto, a historian of ideas, over for dinner one Friday evening at her apartment on Linnégatan in Gothenburg.

Otto was a few years past thirty, as was I, and Agnes a few below, like Maria. Maria was a pretty good cook (we were both big fans of Anthony BourdainII) and had prepared a lamb casserole that had had to spend most of the afternoon on the stove.

She had warned me, though.

It would be a good idea to tread softly, so to speak, with Agnes and Otto (and be a little extra nice to them), since just a few weeks earlier their cat, Frodo—so named after the hero in The Lord of the Rings—had fallen from their third-floor window and subsequently vanished without a trace. One of them, either Agnes or Otto, had forgotten to shut the kitchen window. They had found claw marks on the window ledge, Maria told us. Poor Frodo, a rather diminutive cat, must have been—or at least so I imagined as Maria recounted the story—nonchalantly sniffing around by the window, surveying the street outside, when all of a sudden he lost his balance; in full-blown panic he would have scrabbled at the window ledge, only to slowly but surely—and possibly to the screech of splayed claws on metal (like in a Tom & Jerry cartoon)—lose his grip completely, at which time he must have plunged headlong in the darkness and cold and down onto the pavement, where he, Frodo, this patently indoor cat, hella terrified by the wider world, would presumably have perished. Agnes and Otto hadn’t given up hope, mind; they had plastered half of Kungsladugård and Majorna with posters of little Frodo. Beneath a photo of the timid cat, the whole sorry tale was described. The infuriatingly unshut window. The claw marks on the window ledge. Frodo’s putative nosedive onto the hard tarmac below.

So, Frodo had already been gone a few weeks, and, according to Maria, who knew Agnes well, it was clear that they had started to lose hope just a tad. Maria told me she had heard it in Agnes’s voice when they had last chatted. Notwithstanding all that, I’d venture to say that spirits at dinner were high. Maria and Agnes mostly reminisced about their student days in Lund, and there was only the odd mention of Frodo. Like when Agnes talked about how much she missed the little cat, while Otto caressed her back with a very serious and strained expression, torn between the urge to comfort Agnes and to scrutinize our reactions; as though Otto, model boyfriend that he was, nevertheless to some extent presumed that I, mainly—at whom he cast a suspicious glance when Agnes was perilously close to tears—actually found the whole story, and, indeed, this whole pet fixation, pretty ridiculous, which was basically true. It was awkward. Agnes valiantly squeezed her boyfriend’s hand. They would get through this together. “Yes, yes, we will, Agnes. We will get through this.”

It seemed obvious to me that Frodo—about whom my thoughts were already in the past tense, as ex-Frodo, say—had been something of a “transitional object” for the couple, even if they themselves were naturally incapable of regarding him as such. If Agnes and Otto managed to look after a little cat and were both capable of showing him the requisite tenderness and consideration, thus proving to each other their “adult responsibility” as well as warm feelings for the cute little furball, they could then “level up,” as it were, and perhaps eventually allow themselves to make a real little baby, an undertaking that would reasonably demand both responsibility and maturity.

That Frodo had fallen from the window had, I assumed, not only come as a shock to them both; it was, conceivably, a genuine disaster. They probably wouldn’t say as much openly to each other, but I imagined the issue hovering over them all the same: What if that had happened to a real little baby? The fact of the matter was that such terrible tragedies did occur at times. Every now and then kids did fall from windows, much to society’s horror—and that was certainly no laughing matter.

Truth be told, I myself shuddered slightly at the thought of something like that happening to Maria and me, even though we didn’t yet have kids of our own (and perhaps never would). Admittedly, we did have—or, rather, Maria had—Molly. But the thought of that little white Pomeranian having the audacity to fall from a window felt far too outlandish for me to take seriously.

Agnes also revealed that they had just put up another set of fliers on their block, Poster 2.0, with the headline: Frodo is still missing! So eager was she for us to see it that she whipped out her smartphone and started scrolling through her photos. In the photo on the (ambitiously) laminated, and thereby waterproof, poster, there was an additional picture of Frodo, this time in color, which made the little cat’s unique coat patterns clearer, all to facilitate a correct identification. As I gazed at the image, I strangely enough felt a keen impulse to pretend I’d seen Frodo near my flat in Majorna, but I bit my tongue, tried to rustle up a look of sincere concern, and hoped that it would seem like my heart was bleeding for them, so to speak.

Agnes was, I noted, very keen to emphasize that Frodo was their cat. Agnes’s and Otto’s. They were in this together. On the poster they had given both of their phone numbers. Just in case, I guess. So two numbers. And two email addresses. Yes, I could unequivocally state that they were both indeed traumatized—and at the same time strangely bound—by the tragedy of Frodo’s disappearance.

After dinner we retired to the living room, where Maria and Agnes went on drinking white, while I took another Urquel and Otto a bottle of Stigbergets pilsner from a local brewery. It was only then that the generally breezy atmosphere would take an abrupt turn. It had all started with a pretty uncontroversial conversation about Sweden’s “consensus culture,” and the conformism that could be deemed characteristic of Scandinavian countries. We unanimously agreed to leave unsaid for the moment whether said conformism and consensus culture were for better or for worse. In this respect we were still pretty much of one mind, as we had been about most of what was discussed at dinner. Donald Trump was dumb. Putin was dumb. Margaret Thatcher had, admittedly, been Europe’s (and maybe even the world’s) first female prime minister, and as such perhaps deserved just a smidgen of feminist admiration—not to mention the fact that she’d spoken out against climate change at a relatively early stage—but in the grand scheme of things she, too, had been dumb. A great many people were generally dumb—on that we were all agreed—perhaps especially so in those days.

Thus, with no great friction, we could all agree on the existence of what might be termed a Swedish consensus culture (without ipso facto outing ourselves as exponents of that social norm). Otto soon got onto the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement between the trade unions and employer associations, and the Swedish labor movement’s long and well-documented collaboration with industry, which had largely, he believed, been a boon for Sweden. A statement that was music to my ears, and perhaps lulled me into a false sense of security, for it was then that I thought—since Otto seemed like a “sensible” chap with a certain understanding of social democracy’s reformist strategy—that the time was ripe for me to recount a Jordan B. Peterson anecdote that my friend Johannes had told me during a session at Plankan, our local watering hole.

The anecdote was about an elderly Canadian man who stops at a pedestrian crossing to wait for the light to turn green. It’s early in the morning and freezing cold; maybe minus 4. No car as far as the eye can see. The city is empty, deserted. Still, the man stands there waiting for ages—a long, long time—for the light to go from red to green. For this Canadian pedestrian, to cross on red would be simply unthinkable. It makes no difference that the traffic is pretty much nonexistent, or that he, this lone pedestrian, is in actual fact the only traffic there is! He abides by the law and the rules, he does, for that’s what he has always done. Now, if one were to apply the terms of personality psychology to this man, one would say that he has a strong measure of agreeableness and is also, I assumed, a relatively conscientious person; in this case extreme in his exactitude and complete symbiosis with Canadian society’s wholly rational (and potentially universally applicable) traffic rules. Which I supposed was perhaps why Peterson had used the man as an example of something that to me seemed equally characteristic of many of us Nordic peoples: an almost idiotic readiness to comply with law and order.

“Not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with that, generally speaking,” I said. “But then again it might not be wholly positive. The man undeniably stands there freezing like a poor animal, without needing to!”

Otto replied with grim resolve that there may be some degree of truth to that, certainly, but then he added, surprisingly harshly, and so out of the blue that I almost recoiled, that he actually thought Peterson was “a joke,” and that he couldn’t understand how anyone could take the man seriously. It was as though he hadn’t even listened to my (or, rather, Peterson’s) example of our interesting Nordic psychology. For my part, while recounting the anecdote, I hadn’t quite picked up on his apparent transformation into a completely different—all but crackling—person.

For a second I thought Otto was on the brink of tears. I also got the unpleasant feeling that he could easily throw a punch or something. The thing is, even though I’d bumped into Agnes and Otto a few times in town, I didn’t really know Otto; to me he was a blank page. Maria and Agnes said nothing, but Maria shot me a glance that I interpreted as an expression of surprise and perhaps an appeal for caution. To my knowledge she wasn’t really up on who Peterson was, and in a way neither was I. Agnes, for her part, looked altogether unfussed.

Though I soon suspected that Otto had some sort of beef with Peterson, under the circumstances it didn’t feel right to completely capitulate, so to say. As such, it seemed a not-entirely-inappropriate moment to bring up Carl Cederström’s bizarre Svenska Dagbladet article, in which Cederström, an associate professor in organization studies, described the psychologist as someone who looked up to or even praised bullies and scorned the weak. The article was illustrated with an image of Nelson Muntz from The Simpsons; a classic problem child in the cartoon who, as Peterson would have it, serves as a corrective for keeping weak and pathetic behaviors in check.

“Personally, I have a hard time—a really hard time, frankly…” I said, “believing that Peterson actually looks up to bullies and scorns the weak.” I went on: “Though I haven’t read 12 Rules for Life myself.”

“Yes, but why would anyone read it!” Otto bristled. Something I chose to ignore.

“But wasn’t Cederström’s article extremely black-and-white and weird? Was he not guilty of guilt by association? A clear-cut case of bias, surely? I mean, he went on to mention Breivik, the alt-right, the far right, Trump, and the like. Only ‘lost boys’ admire Peterson, yada yada yada. The only one missing was Hitler!”

“Apparently young men call him and cry down the line,” Otto said jeeringly.

“Even Peterson cries sometimes—on his own YouTube channel!” Agnes jumped in merrily; she didn’t seem at all as outraged by the Canadian psychologist as her partner, for whom the man was clearly an extreme trigger.

“Well, I for one have no intention of reading him,” Otto declared sourly. “He has no substance!” he went on. “There are loads of contemporary conservative thinkers who are better. Way more worth reading. If I had to read conservative thinkers today I’d prefer… well, maybe Mark Steyn or Peter Hitchens. Peterson pretends he’s some kind of expert on myths and folktales, but he takes examples from works that he clearly doesn’t realize were originally written by Hans Christian Andersen…. You know, it actually upsets me to talk about him. I mean, he isn’t good! What sort of people like that person? Well, actually I do know… what they are.”

Otto, the historian of ideas, had more or less hissed that last sentence, and it had also sounded more or less insinuating, as though there was an underlying accusation there. But I couldn’t quite make out if it was directed at me, or he’d simply disappeared into some sort of private sphere of festering conflicts and traumas. Perhaps he had a junkie brother who loved Peterson, somehow, and perhaps this (in Otto’s eyes) loathsome adoration simply constituted yet another alienating element in their relationship. But it would be extraordinary, if not completely absurd, for him to think I belonged to some Swedish alt-right faction or the like. For my political leaning was definitely no secret. I had always been left wing. Much like Otto himself, I assumed, even if he was perhaps to the left of the left on the political spectrum.

In any case, it was clear to me—and I assume the others, too—that Otto’s entire bearing had changed. He looked almost emasculated. Sat there with his shoulders hunched, as though preparing to fend off an attack. His gaze had darkened, his eyes anxious and glassy. For a second I pictured Frodo the missing cat and the Canadian psychologist both materializing in the middle of the room, and the latter—the, in Otto’s view, would-be deranged and fascistoid right-winger—screaming and blustering at the little cat and transitional object: You are small and weak, Frodo! You don’t even deserve to live! But the little cat (and baby substitute) didn’t deserve Peterson’s unreserved taunts. Of course not! Otto’s fists may well have been clenched beneath the low coffee table where they were hidden, and his knuckles may well have been turning white, but still he didn’t straighten his back. The damage was done. He would not recover.

A man (like Peterson), that intellectual scum, I imagined Otto thinking, a man who was clearly willing to rape and pillage his way through the entire Shire—the hobbit Arcadia—was no better than Saruman himself! In that moment it didn’t seem at all inconceivable that that was exactly how Otto saw things. He had lost it, in short, and in almost exactly the same way that associate professor Cederström had lost it in his bizarre article in Svenskan. Both had seemed in thrall to passions; pathos had occupied the place that had once housed their identities; their personalities had completely dissolved; their autonomy dissipated. They had allowed themselves to be hurled into chaos—and ressentiment.

“I just don’t get how anyone can take him seriously,” Otto grumbled, appearing all of a sudden both highly hot and bothered and pathetic all at once, to the point of deep despondency. It was a very strange scene to behold—and from what I could tell the man wasn’t even all that drunk!

“I just don’t get why people take Peterson seriously,” he repeated. “How can anyone take such a character seriously?”

“Still, it seems like a whole lot of people in the world do take him seriously. And he clearly provokes a lot of people, too. In any case, Camille Paglia has called him the greatest Canadian thinker since Marshall McLuhan.”

“But isn’t Paglia mainly just a provocateur?” Agnes wondered.

“Possibly,” I said, “but she’s also a pretty brilliant person.”

Nope, when it came to Paglia I had no plans of backing down an inch. I liked her keenly.

“I would even go so far as to say that she has certain… well, wholly genius aspects…” I went on. “Which for that matter I don’t think Peterson has.”

I’d thrown in that last part mainly to please or even appease Otto, who for at least a second lit up with what I assumed were gratitude and relief; but no, I didn’t think Professor Peterson was a genius, absolutely not. Professor Paglia, on the other hand, had been an idol of mine for years, even if lately—that is, in the late 2010s—I’d been increasingly disappointed by the author of the monumental Sexual Personae.

One of her more recent books, Glittering Images, which discussed Western art—from Nefertiti’s grave to George Lucas’s volcano-planet duel in Revenge of the Sith—hadn’t lived up to my expectations. Besides which, she’d clearly gotten ever more stuck in the role of someone who both wrote and spoke in what she herself termed “sound bites.”

She doesn’t really get to the heart of it, I thought and took a swig of my Urquel, supposing it would be a faux pas to air some of her more famous quotes, such as: “There is no female Mozart because there is no female Jack the Ripper.” Personally, I assumed Paglia was right on that one—since there was de facto no female counterpart to the musical genius of Mozart or Beethoven or Bach (which was kind of sad in a way), and there was de facto no female counterpart to serial killers like Jack the Ripper or Ted Bundy or Jeffrey Dahmer (and a good thing, too!)—but it could take all night to explain why. And it definitely wouldn’t be worth it.

Maria and Agnes had gradually—and perhaps more or less demonstratively—started to turn to each other to discuss other things entirely, as though signaling that it was time for us men to amuse ourselves for a while. It didn’t seem unlikely that they were mildly embarrassed by Otto’s exaggeratedly emotional reaction. But then again they might not have been all that interested in the topic, either. It wasn’t like they were Peterson’s target market, exactly. Or at least not in the same way that Otto and I were.

Neither he nor I, it has to be said, were actually confused or lost young men—or at least not in our own eyes, I guess—but men we were, and we were also at least to some degree involved—Otto more so than myself—in the fields of academia that Peterson considered his targets.

As I would only later come to understand, Peterson saw Marxist, postmodern, and above all feminist-oriented academics—and institutions—as his enemies. In essence, he wanted to close down all the humanities and rebuild them from the ground up, since the world of academia was corrupt beyond redemption. For decades, professors had increasingly become the activist defenders of political correctness and identity politics. But the revolution ate its own children; with time the ideology that they had championed would consume itself. The universities had, in addition, been feminized, according to Peterson; the prestige of having an academic (humanities) background was constantly being devalued. The Canadian psychologist regarded political correctness as an umbrella term for everything that had been de rigueur in academia of late: gender studies, women’s studies, postcolonial studies, intersectionality; so-called whiteness studies.

Now, if Otto identified with Marxism, postmodernism, and feminism—if these were an integral aspect of his academic persona and identity (and, perhaps, his strategy for winning over his peers)—then it possibly wasn’t so strange that he would react as strongly as he did. But the fact that Peterson could seem so monstrous in Otto’s eyes was, at the time, simply astonishing to me, even if I should, admittedly, have suspected that Cederström’s article would be symptomatic—a sort of morphological paradigm—of how many people nevertheless viewed the Canadian psychologist.

Anyhow, I tried to coax Otto into small talk about other things, and after a while the reluctant guest started to tell me about an essay he was working on—I seem to recall it was on the concept of the deep state—but in the wake of the Peterson Debate, any good-mannered banter was well and truly off the table. The atmosphere was irreparably damaged. Peterson had exposed something. A wound? A sore point? Otto’s contention that Peterson was “a joke” was hardly a real argument in my view. On the one hand, that there were contemporary conservative thinkers who were more worth reading seemed plausible enough—that much I could buy (clueless as I was when it came to conservative thinkers); on the other hand, Otto hadn’t really put his finger on what was so conservative about Peterson’s thinking in the first place.

As for me, I still didn’t get what this thinking was, and I certainly didn’t get what about it more or less whipped people like Otto and Cederström up into hysterics when confronted with it. Be that as it may, that I would sooner or later have to read Peterson’s book and make the effort to familiarize myself with his thinking was now seeming increasingly unavoidable.

Once Agnes and Otto had finally left—much earlier than expected (we never got round to playing Trivial Pursuit, which I’d kind of been looking forward to)—both Maria and I breathed a sigh of relief. As I got down to the dishes I had a certain trepidation that Maria would blame me for sabotaging the agreeable vibe, but thankfully she, too, expressed shock at how “weird” Otto had gotten at the mere mention of Peterson’s name. Something that she linked to the “trauma” of Frodo’s disappearance. But it wasn’t like I’d been particularly offensive or unruly in any way. I had led the conversation, as I myself and Maria also saw it, with a demonstratively reasoned, formal tone, which I suppose may in and of itself have provoked the historian of ideas. Nor had I defended Peterson to any great degree. I was also grateful that Agnes hadn’t assumed an overly loyal and uncompromising defensive position vis-à-vis her partner. It would have been sad if Agnes had started to think badly of me, especially seeing as she often dropped in at Maria’s or popped by to join us when we were out in cafés, and so on.

As such, I would be seeing Agnes more than Otto going forward—provided, of course, that my relationship with Maria was to last, which, given that we’d already been together a year and a half, felt extremely feasible.

Fact was, we were very happy together. We had what one would call a “serious” relationship. We also had a number of shared interests. Maria had initially studied art history, but she had changed tack and was now reading librarianship over in Borås, where she had one year left of her training. She was cute, pretty smart, and exciting in erotic respects. Sometimes she would surprise even me by going along with things that I think are difficult or possibly compromising to consciously articulate, even if just to yourself. So long as we were singing from the same song sheet, as it were, and she got what I would term “the concept”—which she seemed to do intuitively, in fact—she was never disgusted or in any way alarmed by the “acts,” “scenarios,” or even “episodes” that occasionally popped up in and of themselves. I’m not sure even I knew where some of them came from.

Now, admittedly we were just two people, but even so I would sometimes find myself thinking of our lovemaking—in group-dynamic terms—as a sort of erotic play community whose diffuse rules emerged—there and then—from an exclusive, chaotic, and unique play sphere. In such a way one could draw parallels between the mystical rules of said play sphere and the so-called willing suspension of disbelief in the reading of literary works. Only if disbelief surfaced—if the fiction didn’t work—would love’s spell, or what one could perhaps also call that of the sexual manuscript, be broken. It would backfire, just as art backfired when said suspension was not achieved.

Sometimes I would even find myself contemplating the German-American psychologist Kurt Lewin’s behavior equation, as described in his 1936 work Principles of Topological Psychology. The equation, B = ƒ(P, E), describes behavior (B) as a function (f) of the person (P) and his or her environment (E). This equation was usually paired with Lewin’s field theory, which posits that an individual’s “life space” comprises a psychological field that includes both the individual and their immediate environment. As such, an individual’s actions can’t be explained—or at all understood—by internal or external factors alone but are rather the product of a complex interplay of internal and external motivations.

A group—or perhaps even just a couple (like Maria and myself)—thus always consisted of more than the sum of its individual contracting parties. When the group—or in this case the couple, or participants in the binary play sphere—was formed, it constituted a unified system with supervening qualities that would be impossible to understand through an individual evaluation of its parts alone.

Apparently it was my turn to take Molly out that night. I don’t know how Maria came to that conclusion, but it didn’t really matter anyway. Besides, I could see that her greatest wish was simply to curl up in bed with Grace Coddington’s Grace: A Memoir and get swept up in its glamorous world. She had gone all in with that book lately. Whenever Maria was reading she was impossible to reach. The strange thing was, she read so slowly that I almost got the feeling she was pretending. It wasn’t that she was bad at English. She just read extremely slowly. Yes, even in Swedish. Ah well.

I stopped dead in my tracks in the hallway, Molly’s lead dangling from my hand, caught by my own reflection in the full-length mirror. I didn’t have any particularly big mirrors at my place, so I found it a little disconcerting to see myself in my own magnificent totality, as it were. No, to be honest it was more that I was genuinely taken aback by how enormously critical I was about my own appearance. Or, more precisely: on that particular night I was surprised by how extremely alien I looked to myself. Namely, I was struck by the fact that my once-so-slender build was starting to exhibit a meatiness that I had never really noticed in myself before. I pinched the layer of subcutaneous fat on my belly and noted that it was still no thicker than one (1) inch (2.54 cm). “Pinch an inch,” as an American woman had said to me once in Berlin. Yeah, I’d fancied her all right. According to her, one inch of subcutaneous fat was a sign of good health.

It struck me now that I not only was, but was increasingly starting to look like, a grown man. My waist wasn’t as slim as before, and if I didn’t consciously suck in my belly and stand up straight it was there; not so big, perhaps, but still. Suddenly I recalled the impression that actor Harvey Keitel had made on me when I saw Jane Campion’s The Piano for the first time. I’d been in my early teens, maybe, or thereabouts. There had been something hypnotic about that fifty-odd-year-old man’s aging, yet muscular, slightly squat and solid physiognomy. Now, it would be unreasonable to claim I felt an erotically tinged attraction to that actor’s physique, if that’s what you’re thinking, but there was absolutely something there. An intense fascination—and perhaps a kind of envy. A longing for a body with weight, strength, and power. After all, I was just a scrawny kid when I saw the film; perhaps back then I didn’t even feel like I had a body. In any case not a body with strength and power, and certainly not weight. I’d thought: Well, my movements may well be nimble, like an elf’s—but at the end of the day an elf is, by its very elfishness, so to speak, masculinity’s antithesis. An elf is an androgynous being. Its slender, sexless body could never be a source of masculine pride.

Well, long gone were the days when I could still catch an air of elfishness in my look. If I’m honest, all things aside, this realization filled me with a sort of happiness. (Though to be fair I was pleasantly intoxicated by this point.) I looked older and I was older—and this didn’t really bother me at all (even though I couldn’t deny that the man now gazing back at me was something of a stranger to himself). It would be extremely narcissistic to feel wronged by the passage of time—though surely wronged wasn’t how I felt, was it? Was it not rather gratitude I felt—yes, actual genuine gratitude—that time had shaped me into a person—at least outwardly—who was perhaps better able to shoulder certain types of responsibility in life? Indeed, perhaps even the sort of “adult responsibility” that I had (not unmockingly) inferred Agnes and Otto were doing their utmost to summon, through their project (or experiment) with the now-missing cat Frodo?

Earlier on in the day, I remembered, Maria had brought up the topic of kids in a way that wasn’t quite a request, but wasn’t entirely without its pretensions, either. We’d been together so long that it was a given that the question would come up sooner or later. While the topic had in fact filled me with sadness, I was pleased that my comments, at least as I saw it, had made me come across as a relatively wise individual. Indeed, when is one really ready for parenthood? No one knows. I’d said: Perhaps no one’s ever ready? Now, later, as I stood before my own reflection, I concluded that at the very least it was unquestionably a plus to be able to take care of oneself. Of someone else. I cast a glance at Molly, who was quivering with anticipation ahead of her short walk. “All right, all right, I’ll get my coat.”

It felt objectionable to imagine Molly as some sort of baby surrogate or biological Tamagotchi, but I couldn’t deny that at dinner I’d also toyed with the idea that perhaps she, too, was a kind of “transitional object” for Maria and me, in the same way that I’d seen Frodo as one for Agnes and Otto.

A kind of experiment. Yes, I’d thought I’d sounded wise during that kids chat, but now I realized that my words could just as easily have seemed like muddled clichés. The child is father of the man, I’d said. Maria had asked me to repeat that possibly age-old saying, and I’d changed the gender: The child is mother of the woman. Maria had contemplated these words in silence for a while. She should get this, I thought. She’s pretty smart and all. But I also realized that the initial breeziness or perhaps impartiality with which we’d embarked upon this most sensitive topic wasn’t all that compatible with such an existential and almost solemn statement.

Hypothetically speaking, any notional babymaking lay some way down the line, at least. Maria would have to finish her studies. Maybe get a job somewhere. But anyway, I felt no acute concern on that front. In days gone by I might have pondered the risk that I was way too damaged by my troubled upbringing to be a good father, but perhaps I’d been too hard on myself. Maria was great. Her family were super bougie, but great all the same; they had, at the very least, produced her, her genius—I was almost tempted to say. Put it this way: If Maria was to fall pregnant, I wouldn’t cry tears of blood. The opposite, in fact! We would handle the situation when or if it should arise. That it would then entail a lifelong commitment and extreme curtailment of my personal freedoms was terrifying. Freedom as I knew it would be over. But had I not started to tire of that same freedom? For many years I had had no responsibility for anyone but myself. At the same time, I couldn’t help but admit that I’d repeatedly failed to take that responsibility. Informally, I still saw myself as a “goof-off.” Someone who did fuckups.

Though, it was true, in recent years I had matured slightly; I’d toed the line.

And now the domain of my responsibility had also expanded to encompass both Maria and her dog, Molly, and there was something beautiful (almost touching) and natural about that. The mere act of taking that little creature for a walk was to take adult responsibility. My responsibility for Maria was different, I expect. Yes, that was probably true. I had no responsibility for her per se. Obviously. It was more like I was accountable to her, in a quasi-juridical sense, as though to a judge or supplementary superego.

But if a man were to suddenly attack her? Of course then I would be compelled to defend her, purely physically. Naturally! In essence it was perhaps more about care than responsibility, I thought, and perhaps that was how it was for Maria, too. Those caring or nurturing traits that she had most certainly extended toward me because she felt, I supposed, and perhaps to a much greater degree than I did, that her self-care comprised my person, too.

If we were to ever have kids, I thought, as I clipped the lead onto Molly’s bright-pink collar with a certain sense of routine, that care would in all likelihood be more or less completely redirected toward them. This was all natural enough in itself, but it could also lead to discord. If in that situation I couldn’t bring myself to be mature enough, indeed, authentically adult as it were; if I hadn’t completely rooted myself in my adulthood, the situation would prove unbearable—and a separation inevitable. Maria’s body and soul would belong to another being entirely. My own offspring. Her entire existence would be symbiotically linked to that little individual.

Not that that that would be strange, I thought and suddenly lurched slightly, nothing strange at all, really, it would simply demand a higher amplitude of adulthood on my part!

I, too, would have to “level up,” and preferably sooner rather than later, given that Maria’s longing for babies was—I suspected—programmed into every cell of her slender body, in roughly the same way that it was programmed into Molly’s, since Molly was a bitch.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (June 11, 2024)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668020197

Raves and Reviews

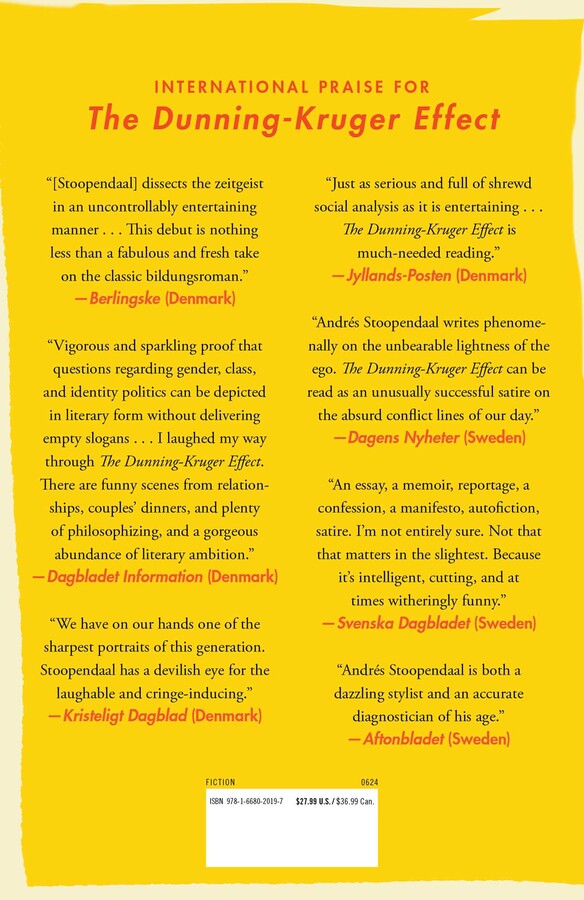

“Darkly, deeply funny and acclaimed... this biting satire portrays a meandering class of millennial men living a seemingly consequence- and purpose-free existence.” —Kirkus

“[A] crackling firework of comic brilliance. The narrator’s self-preoccupation spins so far and uninhibitedly that it inevitably turns into something completely different.” —Svenska Dagbladet (Sweden)

“An intelligent and ironic humor that you rarely find in contemporary literature. . . Original and very entertaining.” —Kapprakt (Sweden)

“The Dunning-Kruger Effect is vigorous and sparkling proof that questions regarding gender, class and identity politics can be depicted in literary form without delivering empty slogans…I laughed my way through The Dunning-Kruger Effect. There are funny scenes from relationships, couples’ dinners, and plenty of philosophizing, and a gorgeous abundance of literary ambition.” —Information (Denmark)

“As a millennial of the depicted demographic group…I feel pinpointed by [Stoopendaal’s] clear-eyed satire of a generation of ‘pretend adults’ with a pathological need to justify work that is neither obviously meaningful nor reflective of their desired identity…We have on our hands one of the sharpest portraits of this generation. Stoopendaal has a devilish eye for the laughable and cringe-inducing.” —Kristeligt Dagblad (Denmark)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Dunning-Kruger Effect Hardcover 9781668020197

- Author Photo (jpg): Andrés Stoopendaal Karl Oskar Sundfelt(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit