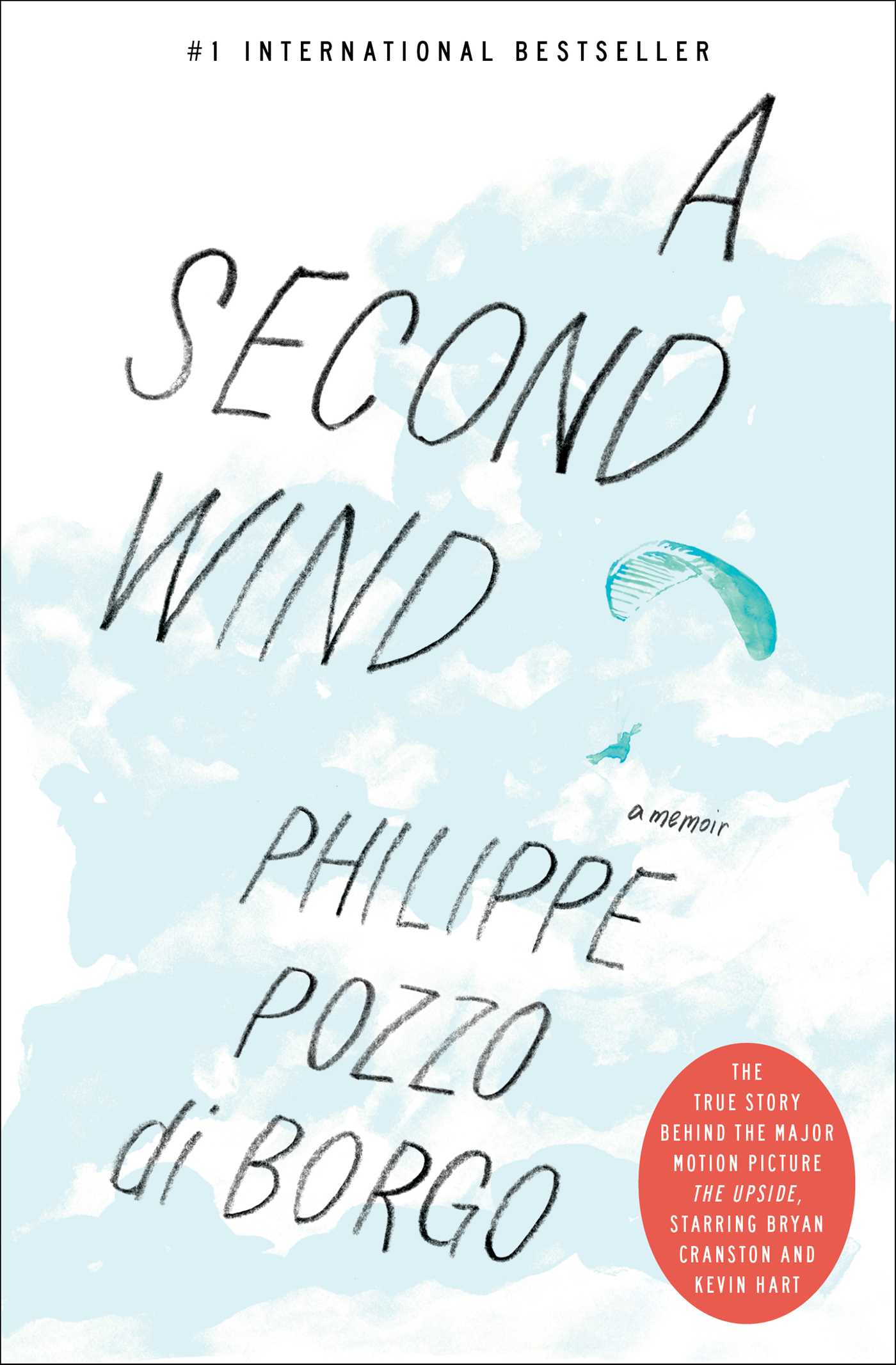

A Second Wind

A Memoir

By Philippe Pozzo di Borgo

LIST PRICE $16.00

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Now a major motion picture—The Upside—starring Bryan Cranston, Kevin Hart, and Nicole Kidman.

Discover the moving and heartfelt #1 international bestseller and inspiration for the film The Upside about an aristocratic Frenchman who is paralyzed in an accident and has to adjust to his new normal with the help of his unlikely caregiver.

As the descendant of two prominent French families and director of a legendary vineyard, Philippe Pozzo di Borgo was not in the habit of asking for help. Then, in 1993, right on the heels of his beloved wife’s diagnosis of a terminal illness, a paragliding accident left him a quadriplegic. He was forty-two years old and unable to do anything—even feed himself—without the help of another person.

Passing his days hidden behind the high walls of his Paris townhouse, Philippe was totally isolated. His paralysis rendered him unable to reach out to others and seemed to make people unwilling to touch him or acknowledge the reality of his existence. For the first time, he learned what it felt like to be excluded.

The only person who seemed not to be bothered by Philippe’s condition was someone who had been marginalized his entire life: Abdel, an unemployed, uninhibited Algerian immigrant from the outskirts of society who would become Philippe's unlikely caretaker. With his tenacious spirit and irreverent sense of humor, Abdel is able to reawaken Philippe’s connection to people and the larger world around him.

A Second Wind is the inspiring true story of two men who refused to ask for help, and then wound up helping each other in more ways than they could imagine.

Discover the moving and heartfelt #1 international bestseller and inspiration for the film The Upside about an aristocratic Frenchman who is paralyzed in an accident and has to adjust to his new normal with the help of his unlikely caregiver.

As the descendant of two prominent French families and director of a legendary vineyard, Philippe Pozzo di Borgo was not in the habit of asking for help. Then, in 1993, right on the heels of his beloved wife’s diagnosis of a terminal illness, a paragliding accident left him a quadriplegic. He was forty-two years old and unable to do anything—even feed himself—without the help of another person.

Passing his days hidden behind the high walls of his Paris townhouse, Philippe was totally isolated. His paralysis rendered him unable to reach out to others and seemed to make people unwilling to touch him or acknowledge the reality of his existence. For the first time, he learned what it felt like to be excluded.

The only person who seemed not to be bothered by Philippe’s condition was someone who had been marginalized his entire life: Abdel, an unemployed, uninhibited Algerian immigrant from the outskirts of society who would become Philippe's unlikely caretaker. With his tenacious spirit and irreverent sense of humor, Abdel is able to reawaken Philippe’s connection to people and the larger world around him.

A Second Wind is the inspiring true story of two men who refused to ask for help, and then wound up helping each other in more ways than they could imagine.

Excerpt

A Second Wind

I Was Born…

AS THE DESCENDANT of the Dukes of Pozzo di Borgo and the Marquis de Vogüé, to say I was born lucky is putting it mildly.

During the Reign of Terror, Carl-Andrea Pozzo di Borgo parted ways with his erstwhile friend Napoleon. While he was still very young, Pozzo di Borgo became prime minister of Corsica under British protection, was forced into exile in Russia, and from there—thanks to his knowledge of the “Ogre”—played his part in the monarchies’ victory. Whereupon he set about amassing a fortune by putting a very high price on the considerable influence he had with the tsar. Dukes, counts, and all the other European nobles swept aside by the French Revolution thanked him handsomely when he helped them to recover their properties and positions. Louis XVIII went so far as to say that Pozzo “was the one who cost him the most.” Through judicious alliances, the Pozzos have handed down this family dough from generation to generation until the present. You can still hear people in the Corsican mountains say that someone is as “rich as a Pozzo.”

Joseph, or “Joe” as he preferred, Duke of Pozzo di Borgo, my grandfather, married an American gold mine, whose grandchildren called her by the English epithet “Granny.” Grandpapa Joe used to relish telling the story of how they got married in 1923. Granny was twenty and had embarked with her mother on a grand tour of Europe to meet the continent’s most eligible bachelors. The two women arrived at the Château de Dangu in Normandy to stay with a Corsican, who turned out to be a head shorter than Granny. Addressing her daughter across the vast dining room table at lunch, Granny’s mother remarked in English (which of course everyone understood), “Don’t you think the duke we saw yesterday had a much prettier château, dear?” This didn’t, however, prevent Granny from choosing the little Corsican over his rival.

When the Left came to power in 1936, Joe Pozzo di Borgo was imprisoned for membership in La Cagoule, an extreme right-wing organization that was hell-bent on overthrowing the Third Republic, even though he wasn’t remotely in sympathy with them. During his stay in La Santé prison, he was visited by his wife and a select group of friends. “The awkward thing about being in prison when people want to see you,” he joked, “is that you can’t send someone to say you’re not in.”

The Corsican Perfettini clan, who had defended our interests on the island since our exile to Russia, were outraged by grandfather’s plight. A delegation went to Paris armed to the teeth and descended on La Santé. Philippe, the Perfettini patriarch, asked the duke for a hit list so they could mete out retribution, only to be advised by Grandfather to go home quietly. On his way out, old Philippe, surprised and disappointed, anxiously asked the duchess, “Is the duke tired?”

Grandfather stopped playing an active role in politics after that and withdrew to his properties: the Parisian town house, the Norman château, the Corsican mountain, and the Dario Palace in Venice. There he held court to a brilliant circle of friends; a center of opposition no matter who was in power. He died when I was fifteen. I can’t think I was ever won over by any of his flights of oratory, dazzling though they were. They seemed to be from another age. But I do remember a party in Paris, when their ballroom was aglitter with diamonds. I was a child. My head came up to the “posteriors” of the glamorous crowd. At one point, to my perplexity, I spotted my dear grandfather’s hand resting on a generously upholstered behind, which did not belong to his lawfully wedded wife.

The Vogüé family’s origins, meanwhile, are lost in the mists of time. As grandfather Pozzo said to grandfather Vogüé (the two patriarchs loathed each other): “At least our titles are recent enough for us to prove they’re genuine!” Robert-Jean de Vogüé didn’t rise to the bait.

Grandfather Vogüé, who was a regular officer, fought in both world wars: he was seventeen in the first, and an N.N. political prisoner in Ziegenhain during the second. N.N.—“Nacht und Nebel” (Night and Fog)—was a Nazi directive in 1941 whereby prisoners were secretly transported to Germany and all knowledge of them was denied to their relatives; in most cases they did not return alive. He was a brave man with deeply felt convictions. Loyal to the code of his knightly ancestors, he saw his family’s inherited privileges as compensation for its services to society: in the Middle Ages, to its defense; in the twentieth century, to its economic development. He married the most beautiful girl of her generation, one of the Moët & Chandon heiresses, and in the 1920s left the army to join the champagne company, which he subsequently ran—and expanded hugely—until his retirement in 1973. In his hands, a small family concern grew into an empire.

These remarkable achievements were the product not only of his strength of character but also his political convictions, which he gathered together at the end of his life in a small book titled, Alerte aux patrons! (A Warning to Employers!) (1974). It is still on my bedside table.

As might be expected, Robert-Jean de Vogüé was heavily criticized by his peers for throwing in his lot so emphatically with the workers. He was even called “the red marquis,” to which his reply was “I am not a marquis, I am a count.” He let them think what they liked about his political allegiances. The financiers who succeeded him destroyed his work. He remains my mentor to this day. Our son is named Robert-Jean after him.

My father, Charles-André, was the eldest of Joe Pozzo di Borgo’s children. He decided to go to work to prove himself. There is an argument, in fact, to say he was the first Pozzo to have a job. It was his way of standing up to his father. He started working on the oil fields in North Africa, then built a career in the oil business through industriousness, enterprise, and consummate efficiency. His professional life took him all over the world, and I followed from an early age. A few years after his father died—he was running an oil company at the time—he put his career on hold to sort out the family’s affairs.

My dear mother had three children in one year: first my older brother Reynier, then me and my twin, Alain, eleven months later. She moved fifteen times during my father’s career, always leaving behind large amounts of bulky furniture and the few friends she’d been able to acquire. As we traveled constantly, she had a nanny to protect her from the worst of our unruliness. I had a habit, for instance, of sitting on Alain when we shared a stroller. He waited many years—and until he was a couple of inches taller than me—before giving me a thrashing that relieved a modicum of his pent-up frustration.

*

NOWADAYS HE pushes me about like a hunchback in my wheelchair. They all tower over me. I refuse to look up.

*

IN TRINIDAD, we spent all our time on the beach, dressed like the locals with whom we swam and played from dusk till dawn. We learned to express ourselves in patois before we could even speak French. In the evening we’d fight in our room. I have a vivid memory of one game, which involved jumping up and down on your bed while pissing on your neighbor’s. North Africa was next: Algeria and Morocco. We discovered school, learned French from a spinster of indeterminate age—a shy, still girlish woman. One day there was a high wind, and as I clung to a telephone pole I saw my puny brother being blown away. Mademoiselle tried to hang on to him, without success. A fence stopped them. For the first time I felt a twinge of jealousy for this twin of mine, who was getting a woman’s full attention.

*

NOW I am a good five feet nine. One hundred and twelve pounds of inert matter, the rest deadweight. No use to anyone.

*

REYNIER QUICKLY distanced himself from us. We gave him an English nickname, Big Fat. Soon the only show in town was The Twins vs. Big Fat, the Enforcer. Keenly aware of his responsibilities as heir, our elder brother wouldn’t hesitate to use his height advantage to pummel us with his platelike hands whenever he felt we needed to be taught a lesson.

*

NOW I am pitiful and cry and can’t hit the people who take advantage of my paralysis.

*

AFTER MOROCCO came London. The nanny this time was called Nancy. I noticed Reynier had a little game he’d play with this beautiful brunette. He’d slip into her bed without my parents knowing and I’d hear him chuckling in there. Without really knowing why, I tried everything I could think of to get into Nancy’s bed. I even tried to catch a fever once by sitting on a boiling hot radiator. I figured that if Nancy would look after me, maybe I’d end up in her bed.… The attempt was short-lived. I had a traitor in the ranks, my bottom. With my buttocks and cheeks on fire, I had to lift the siege.

*

I MISS the sensations that used to prove where I ended and the world began. This body, with its unfathomable boundaries, doesn’t belong to me anymore. Even if someone wants to caress me, their hand never touches me. But these images still move me, despite the fact that I am constantly on fire now.

I Was Born…

AS THE DESCENDANT of the Dukes of Pozzo di Borgo and the Marquis de Vogüé, to say I was born lucky is putting it mildly.

During the Reign of Terror, Carl-Andrea Pozzo di Borgo parted ways with his erstwhile friend Napoleon. While he was still very young, Pozzo di Borgo became prime minister of Corsica under British protection, was forced into exile in Russia, and from there—thanks to his knowledge of the “Ogre”—played his part in the monarchies’ victory. Whereupon he set about amassing a fortune by putting a very high price on the considerable influence he had with the tsar. Dukes, counts, and all the other European nobles swept aside by the French Revolution thanked him handsomely when he helped them to recover their properties and positions. Louis XVIII went so far as to say that Pozzo “was the one who cost him the most.” Through judicious alliances, the Pozzos have handed down this family dough from generation to generation until the present. You can still hear people in the Corsican mountains say that someone is as “rich as a Pozzo.”

Joseph, or “Joe” as he preferred, Duke of Pozzo di Borgo, my grandfather, married an American gold mine, whose grandchildren called her by the English epithet “Granny.” Grandpapa Joe used to relish telling the story of how they got married in 1923. Granny was twenty and had embarked with her mother on a grand tour of Europe to meet the continent’s most eligible bachelors. The two women arrived at the Château de Dangu in Normandy to stay with a Corsican, who turned out to be a head shorter than Granny. Addressing her daughter across the vast dining room table at lunch, Granny’s mother remarked in English (which of course everyone understood), “Don’t you think the duke we saw yesterday had a much prettier château, dear?” This didn’t, however, prevent Granny from choosing the little Corsican over his rival.

When the Left came to power in 1936, Joe Pozzo di Borgo was imprisoned for membership in La Cagoule, an extreme right-wing organization that was hell-bent on overthrowing the Third Republic, even though he wasn’t remotely in sympathy with them. During his stay in La Santé prison, he was visited by his wife and a select group of friends. “The awkward thing about being in prison when people want to see you,” he joked, “is that you can’t send someone to say you’re not in.”

The Corsican Perfettini clan, who had defended our interests on the island since our exile to Russia, were outraged by grandfather’s plight. A delegation went to Paris armed to the teeth and descended on La Santé. Philippe, the Perfettini patriarch, asked the duke for a hit list so they could mete out retribution, only to be advised by Grandfather to go home quietly. On his way out, old Philippe, surprised and disappointed, anxiously asked the duchess, “Is the duke tired?”

Grandfather stopped playing an active role in politics after that and withdrew to his properties: the Parisian town house, the Norman château, the Corsican mountain, and the Dario Palace in Venice. There he held court to a brilliant circle of friends; a center of opposition no matter who was in power. He died when I was fifteen. I can’t think I was ever won over by any of his flights of oratory, dazzling though they were. They seemed to be from another age. But I do remember a party in Paris, when their ballroom was aglitter with diamonds. I was a child. My head came up to the “posteriors” of the glamorous crowd. At one point, to my perplexity, I spotted my dear grandfather’s hand resting on a generously upholstered behind, which did not belong to his lawfully wedded wife.

The Vogüé family’s origins, meanwhile, are lost in the mists of time. As grandfather Pozzo said to grandfather Vogüé (the two patriarchs loathed each other): “At least our titles are recent enough for us to prove they’re genuine!” Robert-Jean de Vogüé didn’t rise to the bait.

Grandfather Vogüé, who was a regular officer, fought in both world wars: he was seventeen in the first, and an N.N. political prisoner in Ziegenhain during the second. N.N.—“Nacht und Nebel” (Night and Fog)—was a Nazi directive in 1941 whereby prisoners were secretly transported to Germany and all knowledge of them was denied to their relatives; in most cases they did not return alive. He was a brave man with deeply felt convictions. Loyal to the code of his knightly ancestors, he saw his family’s inherited privileges as compensation for its services to society: in the Middle Ages, to its defense; in the twentieth century, to its economic development. He married the most beautiful girl of her generation, one of the Moët & Chandon heiresses, and in the 1920s left the army to join the champagne company, which he subsequently ran—and expanded hugely—until his retirement in 1973. In his hands, a small family concern grew into an empire.

These remarkable achievements were the product not only of his strength of character but also his political convictions, which he gathered together at the end of his life in a small book titled, Alerte aux patrons! (A Warning to Employers!) (1974). It is still on my bedside table.

As might be expected, Robert-Jean de Vogüé was heavily criticized by his peers for throwing in his lot so emphatically with the workers. He was even called “the red marquis,” to which his reply was “I am not a marquis, I am a count.” He let them think what they liked about his political allegiances. The financiers who succeeded him destroyed his work. He remains my mentor to this day. Our son is named Robert-Jean after him.

My father, Charles-André, was the eldest of Joe Pozzo di Borgo’s children. He decided to go to work to prove himself. There is an argument, in fact, to say he was the first Pozzo to have a job. It was his way of standing up to his father. He started working on the oil fields in North Africa, then built a career in the oil business through industriousness, enterprise, and consummate efficiency. His professional life took him all over the world, and I followed from an early age. A few years after his father died—he was running an oil company at the time—he put his career on hold to sort out the family’s affairs.

My dear mother had three children in one year: first my older brother Reynier, then me and my twin, Alain, eleven months later. She moved fifteen times during my father’s career, always leaving behind large amounts of bulky furniture and the few friends she’d been able to acquire. As we traveled constantly, she had a nanny to protect her from the worst of our unruliness. I had a habit, for instance, of sitting on Alain when we shared a stroller. He waited many years—and until he was a couple of inches taller than me—before giving me a thrashing that relieved a modicum of his pent-up frustration.

*

NOWADAYS HE pushes me about like a hunchback in my wheelchair. They all tower over me. I refuse to look up.

*

IN TRINIDAD, we spent all our time on the beach, dressed like the locals with whom we swam and played from dusk till dawn. We learned to express ourselves in patois before we could even speak French. In the evening we’d fight in our room. I have a vivid memory of one game, which involved jumping up and down on your bed while pissing on your neighbor’s. North Africa was next: Algeria and Morocco. We discovered school, learned French from a spinster of indeterminate age—a shy, still girlish woman. One day there was a high wind, and as I clung to a telephone pole I saw my puny brother being blown away. Mademoiselle tried to hang on to him, without success. A fence stopped them. For the first time I felt a twinge of jealousy for this twin of mine, who was getting a woman’s full attention.

*

NOW I am a good five feet nine. One hundred and twelve pounds of inert matter, the rest deadweight. No use to anyone.

*

REYNIER QUICKLY distanced himself from us. We gave him an English nickname, Big Fat. Soon the only show in town was The Twins vs. Big Fat, the Enforcer. Keenly aware of his responsibilities as heir, our elder brother wouldn’t hesitate to use his height advantage to pummel us with his platelike hands whenever he felt we needed to be taught a lesson.

*

NOW I am pitiful and cry and can’t hit the people who take advantage of my paralysis.

*

AFTER MOROCCO came London. The nanny this time was called Nancy. I noticed Reynier had a little game he’d play with this beautiful brunette. He’d slip into her bed without my parents knowing and I’d hear him chuckling in there. Without really knowing why, I tried everything I could think of to get into Nancy’s bed. I even tried to catch a fever once by sitting on a boiling hot radiator. I figured that if Nancy would look after me, maybe I’d end up in her bed.… The attempt was short-lived. I had a traitor in the ranks, my bottom. With my buttocks and cheeks on fire, I had to lift the siege.

*

I MISS the sensations that used to prove where I ended and the world began. This body, with its unfathomable boundaries, doesn’t belong to me anymore. Even if someone wants to caress me, their hand never touches me. But these images still move me, despite the fact that I am constantly on fire now.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (February 13, 2018)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501193330

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): A Second Wind Trade Paperback 9781501193330