Diana

Her True Story--in Her Own Words

By Andrew Morton

LIST PRICE $20.00

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

The sensational biography of Princess Diana, written with her cooperation and now featuring exclusive new material to commemorate the 20th anniversary of her death.

When Diana: Her True Story was first published in 1992, it forever changed the way the public viewed the British monarchy. Greeted initially with disbelief and ridicule, the #1 New York Times bestselling biography has become a unique literary classic, not just because of its explosive contents but also because of Diana’s intimate involvement in the publication. Never before had a senior royal spoken in such a raw, unfiltered way about her unhappy marriage, her relationship with the Queen, her extraordinary life inside the House of Windsor, her hopes, her fears, and her dreams. Now, twenty-five years on, biographer Andrew Morton has revisited the secret tapes he and the late princess made to reveal startling new insights into her life and mind. In this fully revised edition of his groundbreaking biography, Morton considers Diana’s legacy and her relevance to the modern royal family.

An icon in life and a legend in death, Diana continues to fascinate. Diana: Her True Story in Her Own Words is the closest we will ever come to her autobiography.

When Diana: Her True Story was first published in 1992, it forever changed the way the public viewed the British monarchy. Greeted initially with disbelief and ridicule, the #1 New York Times bestselling biography has become a unique literary classic, not just because of its explosive contents but also because of Diana’s intimate involvement in the publication. Never before had a senior royal spoken in such a raw, unfiltered way about her unhappy marriage, her relationship with the Queen, her extraordinary life inside the House of Windsor, her hopes, her fears, and her dreams. Now, twenty-five years on, biographer Andrew Morton has revisited the secret tapes he and the late princess made to reveal startling new insights into her life and mind. In this fully revised edition of his groundbreaking biography, Morton considers Diana’s legacy and her relevance to the modern royal family.

An icon in life and a legend in death, Diana continues to fascinate. Diana: Her True Story in Her Own Words is the closest we will ever come to her autobiography.

Excerpt

Diana Foreword

Even at a distance of 25 years, it is a scarcely believable story. Hollywood producers would dismiss the script as much too far-fetched; a beautiful but desperate princess, an unknown writer, an amateur go-between and a book that would change the Princess’s life forever.

In 1991 Princess Diana was approaching 30. She had been in the limelight all of her adult life. Her marriage to Prince Charles in 1981 was described as a ‘fairytale’ by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the popular imagination, the Prince and Princess, blessed with two young sons, Princes William and Harry, were the glamorous and sympathetic face of the House of Windsor. The very idea that their ten-year marriage was in dire trouble was unthinkable – even to the notoriously imaginative tabloid press. Commenting on a joint tour of Brazil that year, the Sunday Mirror described them as presenting a ‘united front to the world’, their closeness sending a ‘shiver of excitement’ around the massed media ranks.

Shortly afterwards I was to learn the unvarnished truth. The unlikely venue for these extraordinary revelations was a working man’s café in the anonymous London suburb of Ruislip. As labourers noisily tucked into plates of egg, bacon and baked beans, I put on a pair of headphones, turned on a battered tape recorder and listened with mounting astonishment to the unmistakable voice of the Princess as she poured out a tale of woe in a rapid stream of consciousness. It was like being transported into a parallel universe, the Princess talking about her unhappiness, her sense of betrayal, her suicide attempts and two things I had never previously heard of: bulimia nervosa, an eating disorder, and a woman called Camilla.

I left the café reeling, scarcely able to believe what I had heard. It was as though I had been admitted into an underground club that was nursing a secret. A dangerous secret. On my way home that evening I kept well away from the edge of the Underground platform, my mind spinning with the same paranoia that infected the movie All the President’s Men, about President Nixon, the Watergate break-in and the subsequent investigation by Woodward and Bernstein.

For nearly ten years I had been writing about the royal family, and was part of the media circus chronicling their work as they toured the globe. It was, as the members of the so-called ‘royal ratpack’ used to say, the most fun you could have with your clothes on. I had met Prince Charles and Princess Diana on numerous occasions at press receptions which were held at the beginning of every tour. Conversations with the Princess were light, bright and trite, usually about my loud ties.

However, life as a royal reporter was not one long jolly. Behind the scenes of the royal theatre, there was a lot of hard work, cultivating contacts inside Buckingham Palace and Kensington Palace, where the Waleses occupied apartments eight and nine, in order to find out about royal life when the grease paint was removed. After writing books about life inside the various palaces, the royal family’s wealth and a biography of the Duchess of York, as well as other works, I had got to know a number of friends and royal staff reasonably well and thought I had a fair idea of what was going on behind the wrought-iron royal gates. Nothing had prepared me for this.

My induction to the truth came courtesy of the man in charge of the tape recorder. I first met Dr James Colthurst in October 1986 on a routine royal visit when he escorted Diana after she opened a new CT scanner in his X-ray department at St Thomas’ hospital in central London. Afterwards, over tea and biscuits, I questioned him about Diana’s visit. It soon became clear that Colthurst, an Old Etonian and son of a baronet whose family have owned Blarney Castle in Ireland for more than a century, had known the Princess for years.

He could become, I thought, a useful contact. We became friendly, enjoying games of squash in the St Thomas’ courts before sitting down to large lunches at a nearby Italian restaurant. Chatty but diffuse, James was happy to talk about any subject but the Princess. Certainly he had known her well enough to visit her when she was a bachelor girl living with her friends at Coleherne Court in Kensington and listen to her mooning about Prince Charles. They had even gone on a skiing holiday to France with a party of friends. Upon her elevation to the role of Princess of Wales, the easy familiarity that characterized her life was lost, Diana still speaking fondly of her ‘Coleherne Court’ but in the past tense.

It was only after she visited St Thomas’ that Colthurst and the Princess renewed their friendship, meeting up for lunch every now and again. By degrees he too was admitted into her secret club and was given glimpses of the real life, rather than the fantasy, endured by the Princess. It was clear that her marriage had failed and that her husband was having an affair with Camilla Parker Bowles, the wife of his Army friend Andrew who held the curious title of Silver Stick in Waiting to the Queen. Mrs Parker Bowles, who lived near to Highgrove, the Waleses’ country home, was so close to the Prince that she regularly hosted dinners and other gatherings for his friends at his Gloucestershire home.

While Colthurst felt he was being let in on a secret, he was not the only one. From the bodyguard who accompanied the Prince on his nocturnal visits to Camilla’s home at Middlewick House, to the butler and chef ordered to prepare and serve a supper they knew the Prince would not be eating as he had gone to see his lover, and the valet who marked up programmes in the TV listings guide Radio Times, to give the impression the Prince had spent a quiet evening at home – all those working for the Prince and Princess were pulled, often against their will, into the deception. His valet Ken Stronach became ill with the daily deceit while their press officer Dickie Arbiter found himself in an ‘impossible position’, maintaining to the world the illusion of happy families while turning a blind eye to the private distance between them.

When Prince Charles broke his arm in a polo accident in June 1990 and was taken to Cirencester hospital, his staff listened intently to the police radios reporting on the progress of the Princess of Wales on her journey from London to the hospital. They were keenly aware that they had to usher out his first visitor – Camilla Parker Bowles – before Diana arrived.

Those in the know realized that the simmering cauldron of deceit, subterfuge and duplicity was going to boil over sooner or later. Every day they asked themselves how long the conspiracy to hoodwink the future queen could continue. Perhaps indefinitely. Or until the Princess was driven mad by those she trusted and admired, who told her, time after weary time, that Camilla was just a friend. Her suspicions, they reasoned, were misplaced, the imaginings, as the Queen Mother told her circle, of ‘a silly girl’.

As Diana was to explain years later in her famous television interview on the BBC’s Panorama programme: ‘Friends on my husband’s side were indicating that I was again unstable, sick and should be put in a home of some sort in order to get better. I was almost an embarrassment.’

Far from being the ravings of a madwoman, Diana’s suspicions were to prove correct, and the painful awareness of the way she had been routinely deceived, not just by her husband but by those inside the royal system, instilled in her an absolute and understandable distrust and contempt for the Establishment. They were attitudes that would shape her behaviour for the rest of her life.

So, as Colthurst tucked into his chicken kiev, he watched as Diana toyed with her wilted salad and spoke with a mixture of anger and sadness about her increasingly intolerable position. She was coming to realize that unless she took drastic action she faced a life sentence of unhappiness and dishonesty. Her first thought was to pack her bags and flee to Australia with her young boys. There were echoes here of the behaviour of her own mother, Frances Shand Kydd, who, following an acrimonious divorce from Diana's father, Earl Spencer, lived as a virtual recluse on the bleak island of Seil in north-west Scotland.

This attitude, however, was merely bravado and resolved nothing. The central issue remained: how to give the public an insight into her side of the story while untangling the legal, emotional and constitutional knots that kept her tethered to the monarchy. It was a genuine predicament. If she had just packed her bags and left, the public and media, who firmly believed in the fairytale, would have considered her behaviour irrational, hysterical and profoundly unbecoming. As far as she was concerned, she had done everything in her power to confront the issue. She had spoken with Charles and been dismissed. Then she had talked to the Queen but faced a blank wall.

Not only did she consider herself to be a prisoner trapped inside a bitterly unfulfilled marriage, she also felt shackled to a wholly unrealistic public image of her royal life and to an unsympathetic royal system which was ruled, in her phrase, by the ‘men in grey suits’. She felt disempowered both as a woman and as a human being. Inside the palace she was treated with kindly condescension, seen as an attractive adornment to her questing husband. ‘And meantime Her Royal Highness will continue doing very little, but doing it very well,’ was the comment by one private secretary at a meeting to discuss future engagements.

Remember, this was the same woman who in 1987 had done more than anyone alive to remove the stigma surrounding the deadly Aids virus when she shook the hand of a terminally ill sufferer at London’s Middlesex Hospital. While she was not able to fully articulate it, Diana had a humanitarian vision for herself that transcended the dull, dutiful round of traditional royal engagements.

As she looked out from her lonely prison, rarely a day passed by without the sound of another door slamming, another lock snapping shut as the fiction of the fairytale was further embellished in the public’s mind. ‘She felt the lid was closing in on her,’ Colthurst later recalled. ‘Unlike other women, she did not have the freedom to leave with her children.’

Like a prisoner condemned for a crime she did not commit, Diana had a crying need to tell the world the truth about her life, the distress she felt and the ambitions she nurtured. Her sense of injustice was profound. Quite simply, she wanted the liberty to speak her mind, the opportunity to tell people the whole story of her life and to let them judge her accordingly.

She felt somehow that if she was able to explain her story to the people, her people, they could truly understand her before it was too late. ‘Let them be my judge,’ she said, confident that her public would not criticize her as harshly as the royal family or the mass media. However, her desire to explain what she saw as the truth of her case was matched by a nagging fear that at any moment her enemies in the Palace would have her classified as mentally ill and locked away. This was no idle fear – when her Panorama interview was screened in 1995, the then Armed Forces Minister, Nicholas Soames, a close friend and former equerry to Prince Charles, described her as displaying ‘the advanced stages of paranoia’.

It gradually dawned on her and her intimate circle that unless the full story of her life was told, the public would never appreciate or understand the reasons behind any actions she decided upon. She chewed over a number of options, from commissioning a series of newspaper articles, to producing a television documentary and publishing a biography of her life. Diana knew her message; she was struggling to find a medium.

How then could she smuggle her message to the outside world? Reviewing Britain’s social landscape she saw that there were few outlets for her story. The House of Windsor is the most influential family in the land, its tentacles wrapped tightly around the decision makers inside television and much of the press. Credible media outlets, the BBC, ITV and the so-called quality newspapers, would have had a collective attack of the vapours if she had signalled that she wanted them to publish the truth of her position. Again, if her story appeared in the tabloid press it would have been dismissed by the Establishment as so much exaggerated rubbish.

What to do? Within her small circle of intimate friends there was sufficient alarm at her current state of mind for several to fear for Diana’s safety. It was known that she had made a number of half-hearted suicide attempts in the past and, as her desperation grew, there was genuine concern that she could take her own life; worries tempered by a balancing belief that ultimately her love for her children could never take her down that path.

At the time she knew that I was researching a biography of her and had been reasonably pleased with an earlier work, Diana’s Diary, mainly because it irritated the Prince of Wales with its detailed description of the Highgrove interior. While researching that book, I had heard hints and rumours that all was not well inside the world of the Waleses. This gossip was but the bland hors d’œuvres before the barely digestible feast of information to come.

Without my fully knowing, Diana was gradually testing me out. She made it clear to Colthurst that she was not averse to him giving me titbits of information. In March 1991 he called me from a phone box on the southern tip of Ireland and told me that Prince Charles’s private secretary Sir Christopher Airey had been sacked. The resulting article in the Sunday Times quietly thrilled Diana, knowing that she had secretly fired a salvo of her own in the direction of her husband. There were other tests which, though not on the scale of riddles posed by Puccini’s Princess Turandot, had to be solved successfully.

She wanted to change her long-time hairdresser Richard Dalton and give another crimper a try. How best to dispense with his services tactfully and without his going to the newspapers to sell his story. Colthurst and I advised her to write him an honest letter, buy him an expensive present and send him on his way. The simple strategy worked.

At this time, what I completely failed to understand was that, for a woman who was living in a system where every significant decision was made by someone else, these small choices and acts of defiance gave her a feeling of control. For her it was tremendously liberating.

At some point she asked Colthurst: ‘Does Andrew want an interview?’ It was by any standards, a mind-blowing suggestion. Princesses don’t usually give interviews, especially when they are the most talked about and photographed princess of the age. These were the days before her Panorama confessional and before Prince Charles went on television to admit his adultery with Mrs Parker Bowles. It was simply unheard of.

Within days of Diana’s suggestion, Colthurst summoned me to that working man’s café in Ruislip to hear a sample of the story she had to tell. I expected it to be a few short sentences about her charity work and her thoughts about her humanitarian ambitions. Wrong again.

After jotting down notes on her suicide attempts, her eating disorders, her husband’s adultery with this woman called Camilla, I hotfooted it to see my publisher, Michael O’Mara. Drawing on a pre-lunch cigar, he listened to a summary of my meeting. Then, suspecting that Colthurst was a clever con man, he announced: ‘If she is so unhappy why is she always smiling in the photographs?’

That went to the heart of the matter. If I was going to swim against the tide of public sentiment regarding the Princess of Wales and her husband, I needed some help. A few scratchy notes taken from a worn-out tape recorder wasn’t going to cut it. What was needed was for the Princess to co-operate as far as she was able in a biography that told the story of her whole life, not just her royal career, thus placing her anxieties, her hopes and her dreams in context. To all intents and purposes the book that resulted from this co-operation, Diana: Her True Story, was her autobiography, the personal testament of a woman who saw herself at the time as voiceless and powerless.

Diana’s initial commitment to the project was immediate and naïvely enthusiastic, as she wondered how many days it would take to publish the book. There was one major stumbling block: how to conduct the interviews with Diana. While I was keen to talk to the Princess directly, this was simply out of the question. At six-foot-four and as a writer known to palace staff, I would hardly be inconspicuous. As soon as it was known that a journalist was inside Kensington Palace – and at this time Prince Charles was nominally in residence – the balloon would go up and Diana would be constrained from any further indiscretions.

Just as Martin Bashir, the television journalist who later interviewed the Princess, was to discover, subterfuge was the only way to circumvent an ever-vigilant royal system. In November 1995, when Bashir conducted his interview, he smuggled his camera crew into Kensington Palace on a quiet Sunday when all her staff were absent.

For my part Diana was interviewed by proxy, James Colthurst the perfect agent to undertake this delicate and, as it turned out, historic mission. Armed with a list of questions I had prepared and his tape recorder, Colthurst set off on his sit-up-and-beg bicycle and pedalled nonchalantly up the drive of Kensington Palace. In May 1991 he conducted the first of six taped interviews that continued through the summer and into autumn, and would ultimately change the way the world saw the Princess and the royal family forever.

Colthurst vividly remembers that first session: ‘We sat in her sitting room. Diana was dressed quite casually in jeans and a blue shirt. Before we began she took the phone off the hook and closed the door. Whenever we were interrupted by someone knocking she removed the body microphone and hid it in cushions on her sofa.

‘For the first 20 minutes of that first interview she was very happy and laughing, especially when talking about incidents during her schooldays. When she got to the heavy issues, the suicide attempts, Camilla and her bulimia, there was an unmistakable sense of release, of unburdening.’

Early in their first conversation Colthurst said to her: ‘Give me a shout if there is something you don’t want me to touch on.’ Her reply was telling: ‘No, no, it’s OK.’ It was clear she wanted the world to know the whole truth, as she saw it.

At times she was annoyed and angered by the way she had been treated by her husband and the royal system, and yet in spite of her raw emotional state, what the Princess had to say was highly believable as many pieces of the jigsaw puzzle of her life began to fall into place. Deep-seated and intense feelings of abandonment and rejection which had dogged her for most of her life came to the surface. Though her childhood was privileged it was also unhappy, Diana describing a bleak emotional landscape where she recalled her guilt for not being born a boy in order to continue the family line, her divorced mother’s tears, her father’s lonely silences and her brother Charles sobbing himself to sleep at night.

While this long-distance interview technique was an imperfect method which gave no opportunity for immediate follow-ups, many questions were simply redundant as, once Diana started talking, she barely paused for breath, her story spilling out. It was a great release and a form of confessional. ‘I was at the end of my tether. I was desperate,’ Diana argued during her subsequent television interview. ‘I think I was so fed up with being seen as someone who was a basket case because I am a very strong person and I know that causes complications in the system that I live in.’

The simple act of talking about her life aroused many memories for Diana, some cheerful, others almost too difficult to put into words. Like a gust of wind across a field of corn, her moods endlessly fluctuated. While she was candid, even whimsical, about her eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and her half-hearted suicide attempts, she was at her lowest ebb when speaking about her early days inside the royal family; ‘the dark ages’, as she referred to them.

Time and again she emphasized her profound sense of destiny: a belief that she would never become Queen but that she had been singled out for a special role. She knew in her heart that it was her fate to travel along a road where the monarchy was secondary to her true vocation. With hindsight her words have a remarkable prescience.

At times she was amusingly animated, particularly when talking about her short life as a bachelor girl. She spoke wistfully about her romance with Prince Charles, sadly about her unhappy childhood and with some passion about the effect Camilla Parker Bowles had had on her life. Indeed, she was so anxious not to be seen as paranoid or foolish, as she had so often been told she was by her husband’s friends, that she showed us several letters and postcards from Mrs Parker Bowles to Prince Charles to prove that she was not imagining their relationship.

These billets-doux, passionate, loving and full of suppressed longing, left my publisher and I in absolutely no doubt that Diana’s suspicions were correct. It was quite evident that Camilla, who called Charles ‘My most precious darling’, was a woman whose love had remained undimmed in spite of the passage of time and the difficulties of pursuing the object of her devotion. ‘I hate not being able to tell you how much I love you’, she wrote, saying how much she longed to be with him and that she was his forever. I particularly remember one vivid passage that read: ‘My heart and body both ache for you.’

Nevertheless, as we were informed by a leading libel lawyer, under strict British law, the fact that you know something to be true does not allow you to say it. Much to Diana’s annoyance, and in spite of overwhelming evidence, I wasn’t at the time able to write that Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles were lovers. Instead I had to allude to a ‘secret friendship’ which had cast a long shadow over the royal marriage. Perhaps more importantly, Diana realized, after reading this cache of correspondence, that any hopes she might have harboured of saving her ten-year-old marriage were utterly doomed.

As much as she was engaged and enthusiastic about the project, the difficult unresolved issues under discussion, particularly her husband’s relationship with Mrs Parker Bowles, would often leave her drained.

As I was working at one remove, I had to second-guess her moods and act accordingly. As a rule of thumb, mornings were times when she was at her most articulate and energetic, particularly if Prince Charles was absent. Those interview sessions were the most productive, Diana speaking with a breathless haste as she poured out her story. She could be unnervingly blithe even when discussing the most intimate and difficult periods of her life.

After she first talked about her suicide attempts, I naturally needed to know a great deal more about when and where they had occurred. I subsequently submitted a raft of specific questions on the subject. When they were presented to her, she treated it as a bit of a joke. ‘He’s pretty well written my obituary,’ she told Colthurst.

On the other hand, if a session was arranged for the afternoon, when her energy was low, her conversation was less fruitful. This was particularly so if she had received some bad press or had a disagreement with her husband. Then it was usually sensible to focus on happy times, her memories of her bachelor days or her two children, Princes William and Harry. In spite of all these handicaps it was clear as the weeks passed that her excitement and involvement with the project was growing, particularly when a title for the book was decided upon. For example, if she knew I was interviewing a trusted friend she would do all she could to help by passing on a further scrap of information, a new anecdote or a correction relating to questions I had submitted earlier.

While she was desperate, almost to the point of imprudence, to see her words appear before a wider public, this mood was tempered by a fear that Buckingham Palace would discover her identity as the secret source, the ‘Deep Throat’, if you will, of my book. We realized that Diana must be given deniability, so that if the Princess was asked: ‘Did you meet Andrew Morton?’ she could answer with a resounding ‘NO’. In fact the Princess was the last one to realize the importance of deniability, but once she knew that she would be kept firmly in the background she became much more enthusiastic.

The first line of deniability was her friends, who were used as cover to disguise her participation. In tandem with writing questions for the Princess, I sent out a number of letters to her circle of friends asking for an interview. They in turn contacted Diana to ask if they should or should not co-operate. It was a patchy process. With some she was encouraging, with others ambivalent, depending on how well she knew them.

Many of those who knew the real Diana truly believed that life couldn’t get any worse for her, arguing that anything was better than her current situation. There was, too, a sense that the dam could burst at any moment, that the story could break early and if it came from the Prince of Wales’ side it would certainly not favour Diana. In this febrile climate, her friends spoke with a frankness and honesty, bravely aware that their actions would bring an unwanted media spotlight upon themselves. Later on in the process, they were even prepared to sign statements confirming their involvement with the book in order to satisfy the doubts of the editor of the Sunday Times, Andrew Neil, who was due to publish extracts from the book. Diana later explained why her friends spoke out: ‘A lot of people saw the distress that my life was in, and they felt it was a supportive thing to help in the way that they did.’

Her friend and astrologer, Debbie Frank, confirmed this mood when she spoke about Diana’s life in the months before the book’s publication. ‘There were times when I would leave a meeting with Diana feeling anxious and concerned because I knew her way was blocked. When Andrew Morton’s book was published I was relieved because the world was let into her secret.’

As my interviews progressed, her friends and other acquaintances confirmed that behind the public smiles and glamorous image was a lonely and unhappy young woman who endured a loveless marriage, was seen as an outsider by the Queen and the rest of the royal family, and was frequently at odds with the aims and objectives of the royal system. Yet one of the heartening aspects of the story was how Diana was striving, with mixed success, to come to terms with her life, transforming from a victim to a woman in control of her destiny. It was a process which the Princess continued until the very end.

After that first session with Dr Colthurst, Diana knew that she had crossed a personal Rubicon. She had thrown away the traditional map of royalty and was striking out on her own with only a hazy idea of the route. The reality was that she was talking by remote control to a man she barely knew, about subjects that, if mishandled, could ruin her reputation. It was by any standards a remarkably reckless and potentially foolhardy exercise. But it worked triumphantly.

During this extraordinary year of secrecy and subterfuge, O’Mara, myself and Colthurst found ourselves not only writing, researching and publishing what was to become a unique literary beast, an ‘authorized unauthorized’ biography, but we also became her shadow court, second-guessing her paid advisers. Everything from handling staff problems, dealing with media crises and even drafting her speeches came under our umbrella.

As Colthurst recalls: ‘The speeches meant a lot to her. It was an area where she realized that she could put across her own message. It gave her a real sense of empowerment and achievement that an audience actually listened to what she had to say rather than just judged her clothes or her hairstyle. She used to ring up very excited if there had been coverage on TV and radio, delighted that she had received praise or even acknowledgement for her thoughts.’

It was an exhilarating and amusing time for us all, helping to shape the future of the world’s most famous young woman right under the noses of Fleet Street and Buckingham Palace.

While it had its lighter moments, this was a high-stakes, winner-take-all game. I had been warned on two separate occasions by former Fleet Street colleagues that, after a series of accurate articles appeared in the Sunday Times about the war of the Waleses, Buckingham Palace was looking hard for my mole. Shortly after one such warning, my office was burgled and files rifled through, but nothing of consequence, apart from a camera, was stolen. From then on, a scrambler telephone and local pay phones were the only sure way that Diana felt secure enough to speak openly. To be extra sure Diana had her sitting room at Kensington Palace ‘swept’ for listening devices – none were found – and routinely shredded every piece of paper that came across her desk. She trusted no one inside the royal system. Or for that matter outside the royal world.

Even with James Colthurst she was never entirely frank. While she raged against her husband’s infidelity, she hid the fact that she had enjoyed a long if sporadic love affair with Major James Hewitt, a tank commander during the first Gulf War, as well as a brief dalliance with old friend James Gilbey. He was later exposed as the male voice on the notorious Squidgygate tapes, telephone conversations between Gilbey and the Princess illicitly recorded over New Year 1989–90. Nor did we have the faintest inkling of her infatuation with the married art dealer Oliver Hoare, who was the object of her love and devotion during the research and writing of Diana: Her True Story.

Looking back, her audacity was breathtaking and one is left wondering if Diana wanted to get her side of the story published first so that she would escape blame for the failure of the marriage. It is a question that will never be properly answered. In fact it was one of Diana’s most enduring and probably intriguing qualities that no matter how close her friends thought they were to her she always held something back, keeping everyone in different compartments.

As the project gained momentum, with numerous phone calls between Colthurst and the Princess dealing with the quotidian details of her life, there was little time – or inclination – for considering her motivations. The priority was to produce a book that reflected her personality accurately, with sympathy and authenticity. Given the shocking nature of Diana’s story, and the secrecy of her involvement, the book had to seem credible and believable.

My first acid test came when the Princess read the manuscript. It was delivered to her piecemeal at any and every opportunity. As with everything else to do with this book it was an amateur and haphazard operation. One such instance happened late one Saturday morning when I had to bicycle to the Brazilian Embassy in Mayfair, where the Princess was having lunch with the Ambassador’s wife, Lucia Flecha de Lima, so that I could pass on the latest offering.

Having been given the opportunity to write the story of the best-loved woman in the world I was obviously anxious to know that I had fairly and accurately interpreted her sentiments and her words. To my great relief she approved; on one occasion Diana was so moved by the poignancy of her own story that she confessed to weeping tears of sorrow.

She made a number of alterations, of fact and emphasis, but only one of any significance, a change which gives an insight into her respect for the Queen. During the interviews she had said that when she threw herself down the stairs at Sandringham while pregnant with Prince William, the Queen was the first on the scene. On the manuscript, Diana altered the text and inserted the Queen Mother’s name, presumably out of deference to the Sovereign.

Other hurdles remained. While a number of Diana’s close friends went on the record in order to underpin the authenticity of the text, the Princess accepted that the book needed a direct link with her own family in order to give it further legitimacy. After some discussion she agreed to supply the Spencer family photograph albums, which contained numerous delightful portraits of the growing Diana, many taken by her late father, Earl Spencer.

Shortly before he died, the Princess sent her father a short note explaining why she had co-operated in a book about her life.

I would like to ask you a special favour.

In particular I would like you to keep that as a secret between us. Please will you do that.

An author who has done me a particular favour is now writing a book on me as Diana, rather than PoW [Princess of Wales]. I trust him completely – and have every reason to do so. He has felt for a long time that the System has rather overshadowed my own life and would like to do a fuller book on me as a person.

It is a chance for my own self to surface a little rather than be lost in the system. I rather see it as a lifebelt against being drowned and it is terribly important to me – and this was brought home to me when I was showing the boys the albums – to remember these things which are me.

She then went on to ask her father to supply the family albums for the book and, hey presto, a few days later several large, red, gold-embossed family albums made their way to the South London offices of my publisher. A number of photographs were selected and duplicated, and the albums returned. The Princess herself helped to identify many of the people who appeared in the photographs with her, a process she greatly enjoyed as it brought back many happy memories, particularly of her teenage years.

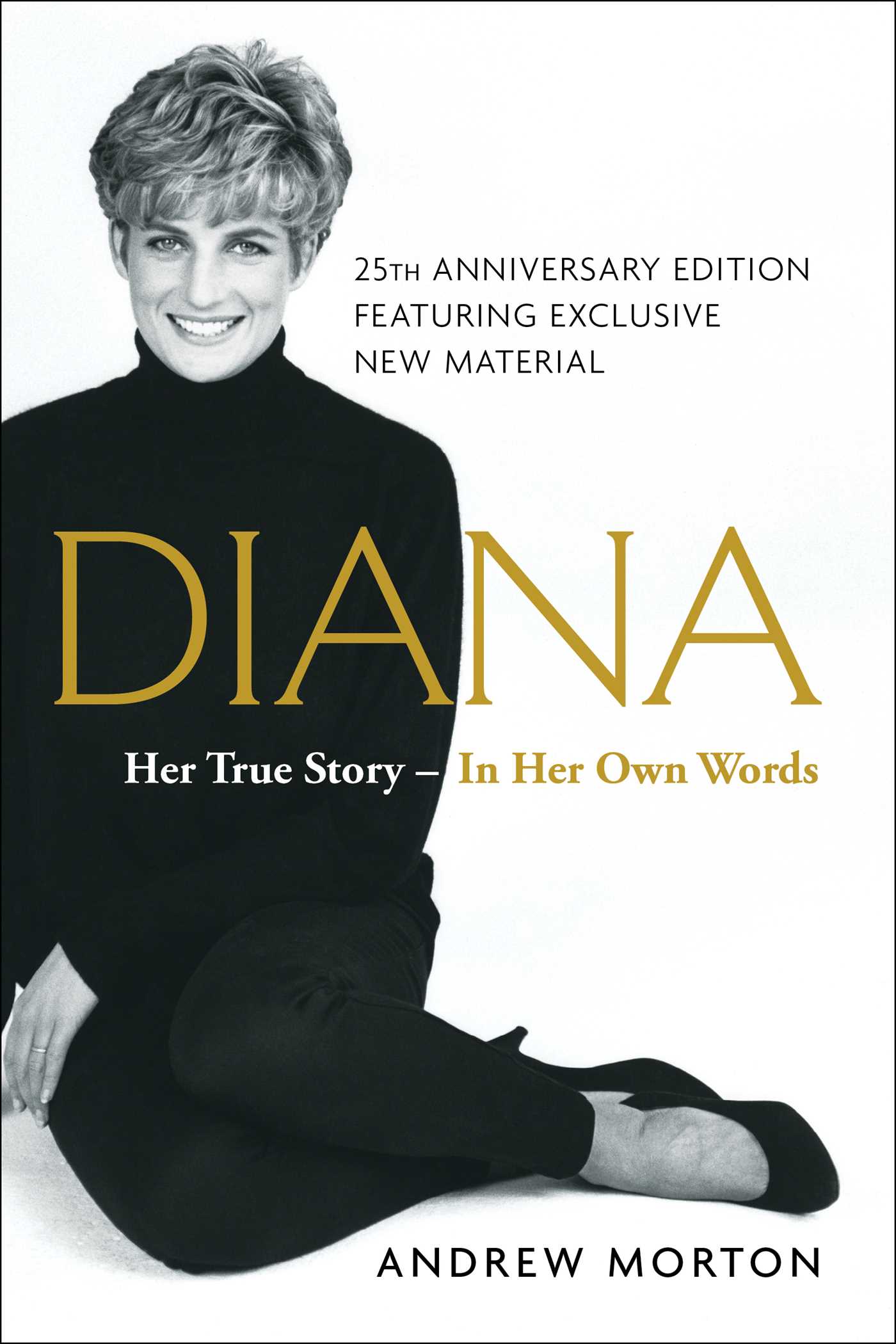

She appreciated, too, that, in order to make the book truly distinctive, we had to have a previously unpublished jacket picture. As it was out of the question that she could attend a photo shoot, she personally chose and supplied the winsome Patrick Demarchelier cover photograph, which was one she kept in her study desk at Kensington Palace. This shot, and those of her and her children, which were used inside, were her particular favourites. We have chosen a hitherto unseen Demarchelier shot for the cover of this anniversary edition of Diana: Her True Story – In Her Own Words.

These were quiet interludes as the storm clouds gathered. The book was due to be published on 16 June 1992 and, as that date approached, the tension at Kensington Palace became palpable. Her newly appointed private secretary, Patrick Jephson, described the atmosphere as ‘like watching a slowly spreading pool of blood seeping from under a locked door’. In January 1992 she was warned that Buckingham Palace was aware of her co-operation with the book, even though at that stage they did not know its contents. Nonetheless she remained steadfast in her involvement with the venture. She knew that there was a cataclysm in the offing but had no doubts that she would survive it.

Even at a distance of 25 years, it is a scarcely believable story. Hollywood producers would dismiss the script as much too far-fetched; a beautiful but desperate princess, an unknown writer, an amateur go-between and a book that would change the Princess’s life forever.

In 1991 Princess Diana was approaching 30. She had been in the limelight all of her adult life. Her marriage to Prince Charles in 1981 was described as a ‘fairytale’ by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the popular imagination, the Prince and Princess, blessed with two young sons, Princes William and Harry, were the glamorous and sympathetic face of the House of Windsor. The very idea that their ten-year marriage was in dire trouble was unthinkable – even to the notoriously imaginative tabloid press. Commenting on a joint tour of Brazil that year, the Sunday Mirror described them as presenting a ‘united front to the world’, their closeness sending a ‘shiver of excitement’ around the massed media ranks.

Shortly afterwards I was to learn the unvarnished truth. The unlikely venue for these extraordinary revelations was a working man’s café in the anonymous London suburb of Ruislip. As labourers noisily tucked into plates of egg, bacon and baked beans, I put on a pair of headphones, turned on a battered tape recorder and listened with mounting astonishment to the unmistakable voice of the Princess as she poured out a tale of woe in a rapid stream of consciousness. It was like being transported into a parallel universe, the Princess talking about her unhappiness, her sense of betrayal, her suicide attempts and two things I had never previously heard of: bulimia nervosa, an eating disorder, and a woman called Camilla.

I left the café reeling, scarcely able to believe what I had heard. It was as though I had been admitted into an underground club that was nursing a secret. A dangerous secret. On my way home that evening I kept well away from the edge of the Underground platform, my mind spinning with the same paranoia that infected the movie All the President’s Men, about President Nixon, the Watergate break-in and the subsequent investigation by Woodward and Bernstein.

For nearly ten years I had been writing about the royal family, and was part of the media circus chronicling their work as they toured the globe. It was, as the members of the so-called ‘royal ratpack’ used to say, the most fun you could have with your clothes on. I had met Prince Charles and Princess Diana on numerous occasions at press receptions which were held at the beginning of every tour. Conversations with the Princess were light, bright and trite, usually about my loud ties.

However, life as a royal reporter was not one long jolly. Behind the scenes of the royal theatre, there was a lot of hard work, cultivating contacts inside Buckingham Palace and Kensington Palace, where the Waleses occupied apartments eight and nine, in order to find out about royal life when the grease paint was removed. After writing books about life inside the various palaces, the royal family’s wealth and a biography of the Duchess of York, as well as other works, I had got to know a number of friends and royal staff reasonably well and thought I had a fair idea of what was going on behind the wrought-iron royal gates. Nothing had prepared me for this.

My induction to the truth came courtesy of the man in charge of the tape recorder. I first met Dr James Colthurst in October 1986 on a routine royal visit when he escorted Diana after she opened a new CT scanner in his X-ray department at St Thomas’ hospital in central London. Afterwards, over tea and biscuits, I questioned him about Diana’s visit. It soon became clear that Colthurst, an Old Etonian and son of a baronet whose family have owned Blarney Castle in Ireland for more than a century, had known the Princess for years.

He could become, I thought, a useful contact. We became friendly, enjoying games of squash in the St Thomas’ courts before sitting down to large lunches at a nearby Italian restaurant. Chatty but diffuse, James was happy to talk about any subject but the Princess. Certainly he had known her well enough to visit her when she was a bachelor girl living with her friends at Coleherne Court in Kensington and listen to her mooning about Prince Charles. They had even gone on a skiing holiday to France with a party of friends. Upon her elevation to the role of Princess of Wales, the easy familiarity that characterized her life was lost, Diana still speaking fondly of her ‘Coleherne Court’ but in the past tense.

It was only after she visited St Thomas’ that Colthurst and the Princess renewed their friendship, meeting up for lunch every now and again. By degrees he too was admitted into her secret club and was given glimpses of the real life, rather than the fantasy, endured by the Princess. It was clear that her marriage had failed and that her husband was having an affair with Camilla Parker Bowles, the wife of his Army friend Andrew who held the curious title of Silver Stick in Waiting to the Queen. Mrs Parker Bowles, who lived near to Highgrove, the Waleses’ country home, was so close to the Prince that she regularly hosted dinners and other gatherings for his friends at his Gloucestershire home.

While Colthurst felt he was being let in on a secret, he was not the only one. From the bodyguard who accompanied the Prince on his nocturnal visits to Camilla’s home at Middlewick House, to the butler and chef ordered to prepare and serve a supper they knew the Prince would not be eating as he had gone to see his lover, and the valet who marked up programmes in the TV listings guide Radio Times, to give the impression the Prince had spent a quiet evening at home – all those working for the Prince and Princess were pulled, often against their will, into the deception. His valet Ken Stronach became ill with the daily deceit while their press officer Dickie Arbiter found himself in an ‘impossible position’, maintaining to the world the illusion of happy families while turning a blind eye to the private distance between them.

When Prince Charles broke his arm in a polo accident in June 1990 and was taken to Cirencester hospital, his staff listened intently to the police radios reporting on the progress of the Princess of Wales on her journey from London to the hospital. They were keenly aware that they had to usher out his first visitor – Camilla Parker Bowles – before Diana arrived.

Those in the know realized that the simmering cauldron of deceit, subterfuge and duplicity was going to boil over sooner or later. Every day they asked themselves how long the conspiracy to hoodwink the future queen could continue. Perhaps indefinitely. Or until the Princess was driven mad by those she trusted and admired, who told her, time after weary time, that Camilla was just a friend. Her suspicions, they reasoned, were misplaced, the imaginings, as the Queen Mother told her circle, of ‘a silly girl’.

As Diana was to explain years later in her famous television interview on the BBC’s Panorama programme: ‘Friends on my husband’s side were indicating that I was again unstable, sick and should be put in a home of some sort in order to get better. I was almost an embarrassment.’

Far from being the ravings of a madwoman, Diana’s suspicions were to prove correct, and the painful awareness of the way she had been routinely deceived, not just by her husband but by those inside the royal system, instilled in her an absolute and understandable distrust and contempt for the Establishment. They were attitudes that would shape her behaviour for the rest of her life.

So, as Colthurst tucked into his chicken kiev, he watched as Diana toyed with her wilted salad and spoke with a mixture of anger and sadness about her increasingly intolerable position. She was coming to realize that unless she took drastic action she faced a life sentence of unhappiness and dishonesty. Her first thought was to pack her bags and flee to Australia with her young boys. There were echoes here of the behaviour of her own mother, Frances Shand Kydd, who, following an acrimonious divorce from Diana's father, Earl Spencer, lived as a virtual recluse on the bleak island of Seil in north-west Scotland.

This attitude, however, was merely bravado and resolved nothing. The central issue remained: how to give the public an insight into her side of the story while untangling the legal, emotional and constitutional knots that kept her tethered to the monarchy. It was a genuine predicament. If she had just packed her bags and left, the public and media, who firmly believed in the fairytale, would have considered her behaviour irrational, hysterical and profoundly unbecoming. As far as she was concerned, she had done everything in her power to confront the issue. She had spoken with Charles and been dismissed. Then she had talked to the Queen but faced a blank wall.

Not only did she consider herself to be a prisoner trapped inside a bitterly unfulfilled marriage, she also felt shackled to a wholly unrealistic public image of her royal life and to an unsympathetic royal system which was ruled, in her phrase, by the ‘men in grey suits’. She felt disempowered both as a woman and as a human being. Inside the palace she was treated with kindly condescension, seen as an attractive adornment to her questing husband. ‘And meantime Her Royal Highness will continue doing very little, but doing it very well,’ was the comment by one private secretary at a meeting to discuss future engagements.

Remember, this was the same woman who in 1987 had done more than anyone alive to remove the stigma surrounding the deadly Aids virus when she shook the hand of a terminally ill sufferer at London’s Middlesex Hospital. While she was not able to fully articulate it, Diana had a humanitarian vision for herself that transcended the dull, dutiful round of traditional royal engagements.

As she looked out from her lonely prison, rarely a day passed by without the sound of another door slamming, another lock snapping shut as the fiction of the fairytale was further embellished in the public’s mind. ‘She felt the lid was closing in on her,’ Colthurst later recalled. ‘Unlike other women, she did not have the freedom to leave with her children.’

Like a prisoner condemned for a crime she did not commit, Diana had a crying need to tell the world the truth about her life, the distress she felt and the ambitions she nurtured. Her sense of injustice was profound. Quite simply, she wanted the liberty to speak her mind, the opportunity to tell people the whole story of her life and to let them judge her accordingly.

She felt somehow that if she was able to explain her story to the people, her people, they could truly understand her before it was too late. ‘Let them be my judge,’ she said, confident that her public would not criticize her as harshly as the royal family or the mass media. However, her desire to explain what she saw as the truth of her case was matched by a nagging fear that at any moment her enemies in the Palace would have her classified as mentally ill and locked away. This was no idle fear – when her Panorama interview was screened in 1995, the then Armed Forces Minister, Nicholas Soames, a close friend and former equerry to Prince Charles, described her as displaying ‘the advanced stages of paranoia’.

It gradually dawned on her and her intimate circle that unless the full story of her life was told, the public would never appreciate or understand the reasons behind any actions she decided upon. She chewed over a number of options, from commissioning a series of newspaper articles, to producing a television documentary and publishing a biography of her life. Diana knew her message; she was struggling to find a medium.

How then could she smuggle her message to the outside world? Reviewing Britain’s social landscape she saw that there were few outlets for her story. The House of Windsor is the most influential family in the land, its tentacles wrapped tightly around the decision makers inside television and much of the press. Credible media outlets, the BBC, ITV and the so-called quality newspapers, would have had a collective attack of the vapours if she had signalled that she wanted them to publish the truth of her position. Again, if her story appeared in the tabloid press it would have been dismissed by the Establishment as so much exaggerated rubbish.

What to do? Within her small circle of intimate friends there was sufficient alarm at her current state of mind for several to fear for Diana’s safety. It was known that she had made a number of half-hearted suicide attempts in the past and, as her desperation grew, there was genuine concern that she could take her own life; worries tempered by a balancing belief that ultimately her love for her children could never take her down that path.

At the time she knew that I was researching a biography of her and had been reasonably pleased with an earlier work, Diana’s Diary, mainly because it irritated the Prince of Wales with its detailed description of the Highgrove interior. While researching that book, I had heard hints and rumours that all was not well inside the world of the Waleses. This gossip was but the bland hors d’œuvres before the barely digestible feast of information to come.

Without my fully knowing, Diana was gradually testing me out. She made it clear to Colthurst that she was not averse to him giving me titbits of information. In March 1991 he called me from a phone box on the southern tip of Ireland and told me that Prince Charles’s private secretary Sir Christopher Airey had been sacked. The resulting article in the Sunday Times quietly thrilled Diana, knowing that she had secretly fired a salvo of her own in the direction of her husband. There were other tests which, though not on the scale of riddles posed by Puccini’s Princess Turandot, had to be solved successfully.

She wanted to change her long-time hairdresser Richard Dalton and give another crimper a try. How best to dispense with his services tactfully and without his going to the newspapers to sell his story. Colthurst and I advised her to write him an honest letter, buy him an expensive present and send him on his way. The simple strategy worked.

At this time, what I completely failed to understand was that, for a woman who was living in a system where every significant decision was made by someone else, these small choices and acts of defiance gave her a feeling of control. For her it was tremendously liberating.

At some point she asked Colthurst: ‘Does Andrew want an interview?’ It was by any standards, a mind-blowing suggestion. Princesses don’t usually give interviews, especially when they are the most talked about and photographed princess of the age. These were the days before her Panorama confessional and before Prince Charles went on television to admit his adultery with Mrs Parker Bowles. It was simply unheard of.

Within days of Diana’s suggestion, Colthurst summoned me to that working man’s café in Ruislip to hear a sample of the story she had to tell. I expected it to be a few short sentences about her charity work and her thoughts about her humanitarian ambitions. Wrong again.

After jotting down notes on her suicide attempts, her eating disorders, her husband’s adultery with this woman called Camilla, I hotfooted it to see my publisher, Michael O’Mara. Drawing on a pre-lunch cigar, he listened to a summary of my meeting. Then, suspecting that Colthurst was a clever con man, he announced: ‘If she is so unhappy why is she always smiling in the photographs?’

That went to the heart of the matter. If I was going to swim against the tide of public sentiment regarding the Princess of Wales and her husband, I needed some help. A few scratchy notes taken from a worn-out tape recorder wasn’t going to cut it. What was needed was for the Princess to co-operate as far as she was able in a biography that told the story of her whole life, not just her royal career, thus placing her anxieties, her hopes and her dreams in context. To all intents and purposes the book that resulted from this co-operation, Diana: Her True Story, was her autobiography, the personal testament of a woman who saw herself at the time as voiceless and powerless.

Diana’s initial commitment to the project was immediate and naïvely enthusiastic, as she wondered how many days it would take to publish the book. There was one major stumbling block: how to conduct the interviews with Diana. While I was keen to talk to the Princess directly, this was simply out of the question. At six-foot-four and as a writer known to palace staff, I would hardly be inconspicuous. As soon as it was known that a journalist was inside Kensington Palace – and at this time Prince Charles was nominally in residence – the balloon would go up and Diana would be constrained from any further indiscretions.

Just as Martin Bashir, the television journalist who later interviewed the Princess, was to discover, subterfuge was the only way to circumvent an ever-vigilant royal system. In November 1995, when Bashir conducted his interview, he smuggled his camera crew into Kensington Palace on a quiet Sunday when all her staff were absent.

For my part Diana was interviewed by proxy, James Colthurst the perfect agent to undertake this delicate and, as it turned out, historic mission. Armed with a list of questions I had prepared and his tape recorder, Colthurst set off on his sit-up-and-beg bicycle and pedalled nonchalantly up the drive of Kensington Palace. In May 1991 he conducted the first of six taped interviews that continued through the summer and into autumn, and would ultimately change the way the world saw the Princess and the royal family forever.

Colthurst vividly remembers that first session: ‘We sat in her sitting room. Diana was dressed quite casually in jeans and a blue shirt. Before we began she took the phone off the hook and closed the door. Whenever we were interrupted by someone knocking she removed the body microphone and hid it in cushions on her sofa.

‘For the first 20 minutes of that first interview she was very happy and laughing, especially when talking about incidents during her schooldays. When she got to the heavy issues, the suicide attempts, Camilla and her bulimia, there was an unmistakable sense of release, of unburdening.’

Early in their first conversation Colthurst said to her: ‘Give me a shout if there is something you don’t want me to touch on.’ Her reply was telling: ‘No, no, it’s OK.’ It was clear she wanted the world to know the whole truth, as she saw it.

At times she was annoyed and angered by the way she had been treated by her husband and the royal system, and yet in spite of her raw emotional state, what the Princess had to say was highly believable as many pieces of the jigsaw puzzle of her life began to fall into place. Deep-seated and intense feelings of abandonment and rejection which had dogged her for most of her life came to the surface. Though her childhood was privileged it was also unhappy, Diana describing a bleak emotional landscape where she recalled her guilt for not being born a boy in order to continue the family line, her divorced mother’s tears, her father’s lonely silences and her brother Charles sobbing himself to sleep at night.

While this long-distance interview technique was an imperfect method which gave no opportunity for immediate follow-ups, many questions were simply redundant as, once Diana started talking, she barely paused for breath, her story spilling out. It was a great release and a form of confessional. ‘I was at the end of my tether. I was desperate,’ Diana argued during her subsequent television interview. ‘I think I was so fed up with being seen as someone who was a basket case because I am a very strong person and I know that causes complications in the system that I live in.’

The simple act of talking about her life aroused many memories for Diana, some cheerful, others almost too difficult to put into words. Like a gust of wind across a field of corn, her moods endlessly fluctuated. While she was candid, even whimsical, about her eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and her half-hearted suicide attempts, she was at her lowest ebb when speaking about her early days inside the royal family; ‘the dark ages’, as she referred to them.

Time and again she emphasized her profound sense of destiny: a belief that she would never become Queen but that she had been singled out for a special role. She knew in her heart that it was her fate to travel along a road where the monarchy was secondary to her true vocation. With hindsight her words have a remarkable prescience.

At times she was amusingly animated, particularly when talking about her short life as a bachelor girl. She spoke wistfully about her romance with Prince Charles, sadly about her unhappy childhood and with some passion about the effect Camilla Parker Bowles had had on her life. Indeed, she was so anxious not to be seen as paranoid or foolish, as she had so often been told she was by her husband’s friends, that she showed us several letters and postcards from Mrs Parker Bowles to Prince Charles to prove that she was not imagining their relationship.

These billets-doux, passionate, loving and full of suppressed longing, left my publisher and I in absolutely no doubt that Diana’s suspicions were correct. It was quite evident that Camilla, who called Charles ‘My most precious darling’, was a woman whose love had remained undimmed in spite of the passage of time and the difficulties of pursuing the object of her devotion. ‘I hate not being able to tell you how much I love you’, she wrote, saying how much she longed to be with him and that she was his forever. I particularly remember one vivid passage that read: ‘My heart and body both ache for you.’

Nevertheless, as we were informed by a leading libel lawyer, under strict British law, the fact that you know something to be true does not allow you to say it. Much to Diana’s annoyance, and in spite of overwhelming evidence, I wasn’t at the time able to write that Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles were lovers. Instead I had to allude to a ‘secret friendship’ which had cast a long shadow over the royal marriage. Perhaps more importantly, Diana realized, after reading this cache of correspondence, that any hopes she might have harboured of saving her ten-year-old marriage were utterly doomed.

As much as she was engaged and enthusiastic about the project, the difficult unresolved issues under discussion, particularly her husband’s relationship with Mrs Parker Bowles, would often leave her drained.

As I was working at one remove, I had to second-guess her moods and act accordingly. As a rule of thumb, mornings were times when she was at her most articulate and energetic, particularly if Prince Charles was absent. Those interview sessions were the most productive, Diana speaking with a breathless haste as she poured out her story. She could be unnervingly blithe even when discussing the most intimate and difficult periods of her life.

After she first talked about her suicide attempts, I naturally needed to know a great deal more about when and where they had occurred. I subsequently submitted a raft of specific questions on the subject. When they were presented to her, she treated it as a bit of a joke. ‘He’s pretty well written my obituary,’ she told Colthurst.

On the other hand, if a session was arranged for the afternoon, when her energy was low, her conversation was less fruitful. This was particularly so if she had received some bad press or had a disagreement with her husband. Then it was usually sensible to focus on happy times, her memories of her bachelor days or her two children, Princes William and Harry. In spite of all these handicaps it was clear as the weeks passed that her excitement and involvement with the project was growing, particularly when a title for the book was decided upon. For example, if she knew I was interviewing a trusted friend she would do all she could to help by passing on a further scrap of information, a new anecdote or a correction relating to questions I had submitted earlier.

While she was desperate, almost to the point of imprudence, to see her words appear before a wider public, this mood was tempered by a fear that Buckingham Palace would discover her identity as the secret source, the ‘Deep Throat’, if you will, of my book. We realized that Diana must be given deniability, so that if the Princess was asked: ‘Did you meet Andrew Morton?’ she could answer with a resounding ‘NO’. In fact the Princess was the last one to realize the importance of deniability, but once she knew that she would be kept firmly in the background she became much more enthusiastic.

The first line of deniability was her friends, who were used as cover to disguise her participation. In tandem with writing questions for the Princess, I sent out a number of letters to her circle of friends asking for an interview. They in turn contacted Diana to ask if they should or should not co-operate. It was a patchy process. With some she was encouraging, with others ambivalent, depending on how well she knew them.

Many of those who knew the real Diana truly believed that life couldn’t get any worse for her, arguing that anything was better than her current situation. There was, too, a sense that the dam could burst at any moment, that the story could break early and if it came from the Prince of Wales’ side it would certainly not favour Diana. In this febrile climate, her friends spoke with a frankness and honesty, bravely aware that their actions would bring an unwanted media spotlight upon themselves. Later on in the process, they were even prepared to sign statements confirming their involvement with the book in order to satisfy the doubts of the editor of the Sunday Times, Andrew Neil, who was due to publish extracts from the book. Diana later explained why her friends spoke out: ‘A lot of people saw the distress that my life was in, and they felt it was a supportive thing to help in the way that they did.’

Her friend and astrologer, Debbie Frank, confirmed this mood when she spoke about Diana’s life in the months before the book’s publication. ‘There were times when I would leave a meeting with Diana feeling anxious and concerned because I knew her way was blocked. When Andrew Morton’s book was published I was relieved because the world was let into her secret.’

As my interviews progressed, her friends and other acquaintances confirmed that behind the public smiles and glamorous image was a lonely and unhappy young woman who endured a loveless marriage, was seen as an outsider by the Queen and the rest of the royal family, and was frequently at odds with the aims and objectives of the royal system. Yet one of the heartening aspects of the story was how Diana was striving, with mixed success, to come to terms with her life, transforming from a victim to a woman in control of her destiny. It was a process which the Princess continued until the very end.

After that first session with Dr Colthurst, Diana knew that she had crossed a personal Rubicon. She had thrown away the traditional map of royalty and was striking out on her own with only a hazy idea of the route. The reality was that she was talking by remote control to a man she barely knew, about subjects that, if mishandled, could ruin her reputation. It was by any standards a remarkably reckless and potentially foolhardy exercise. But it worked triumphantly.

During this extraordinary year of secrecy and subterfuge, O’Mara, myself and Colthurst found ourselves not only writing, researching and publishing what was to become a unique literary beast, an ‘authorized unauthorized’ biography, but we also became her shadow court, second-guessing her paid advisers. Everything from handling staff problems, dealing with media crises and even drafting her speeches came under our umbrella.

As Colthurst recalls: ‘The speeches meant a lot to her. It was an area where she realized that she could put across her own message. It gave her a real sense of empowerment and achievement that an audience actually listened to what she had to say rather than just judged her clothes or her hairstyle. She used to ring up very excited if there had been coverage on TV and radio, delighted that she had received praise or even acknowledgement for her thoughts.’

It was an exhilarating and amusing time for us all, helping to shape the future of the world’s most famous young woman right under the noses of Fleet Street and Buckingham Palace.

While it had its lighter moments, this was a high-stakes, winner-take-all game. I had been warned on two separate occasions by former Fleet Street colleagues that, after a series of accurate articles appeared in the Sunday Times about the war of the Waleses, Buckingham Palace was looking hard for my mole. Shortly after one such warning, my office was burgled and files rifled through, but nothing of consequence, apart from a camera, was stolen. From then on, a scrambler telephone and local pay phones were the only sure way that Diana felt secure enough to speak openly. To be extra sure Diana had her sitting room at Kensington Palace ‘swept’ for listening devices – none were found – and routinely shredded every piece of paper that came across her desk. She trusted no one inside the royal system. Or for that matter outside the royal world.

Even with James Colthurst she was never entirely frank. While she raged against her husband’s infidelity, she hid the fact that she had enjoyed a long if sporadic love affair with Major James Hewitt, a tank commander during the first Gulf War, as well as a brief dalliance with old friend James Gilbey. He was later exposed as the male voice on the notorious Squidgygate tapes, telephone conversations between Gilbey and the Princess illicitly recorded over New Year 1989–90. Nor did we have the faintest inkling of her infatuation with the married art dealer Oliver Hoare, who was the object of her love and devotion during the research and writing of Diana: Her True Story.

Looking back, her audacity was breathtaking and one is left wondering if Diana wanted to get her side of the story published first so that she would escape blame for the failure of the marriage. It is a question that will never be properly answered. In fact it was one of Diana’s most enduring and probably intriguing qualities that no matter how close her friends thought they were to her she always held something back, keeping everyone in different compartments.

As the project gained momentum, with numerous phone calls between Colthurst and the Princess dealing with the quotidian details of her life, there was little time – or inclination – for considering her motivations. The priority was to produce a book that reflected her personality accurately, with sympathy and authenticity. Given the shocking nature of Diana’s story, and the secrecy of her involvement, the book had to seem credible and believable.

My first acid test came when the Princess read the manuscript. It was delivered to her piecemeal at any and every opportunity. As with everything else to do with this book it was an amateur and haphazard operation. One such instance happened late one Saturday morning when I had to bicycle to the Brazilian Embassy in Mayfair, where the Princess was having lunch with the Ambassador’s wife, Lucia Flecha de Lima, so that I could pass on the latest offering.

Having been given the opportunity to write the story of the best-loved woman in the world I was obviously anxious to know that I had fairly and accurately interpreted her sentiments and her words. To my great relief she approved; on one occasion Diana was so moved by the poignancy of her own story that she confessed to weeping tears of sorrow.

She made a number of alterations, of fact and emphasis, but only one of any significance, a change which gives an insight into her respect for the Queen. During the interviews she had said that when she threw herself down the stairs at Sandringham while pregnant with Prince William, the Queen was the first on the scene. On the manuscript, Diana altered the text and inserted the Queen Mother’s name, presumably out of deference to the Sovereign.

Other hurdles remained. While a number of Diana’s close friends went on the record in order to underpin the authenticity of the text, the Princess accepted that the book needed a direct link with her own family in order to give it further legitimacy. After some discussion she agreed to supply the Spencer family photograph albums, which contained numerous delightful portraits of the growing Diana, many taken by her late father, Earl Spencer.

Shortly before he died, the Princess sent her father a short note explaining why she had co-operated in a book about her life.

I would like to ask you a special favour.

In particular I would like you to keep that as a secret between us. Please will you do that.

An author who has done me a particular favour is now writing a book on me as Diana, rather than PoW [Princess of Wales]. I trust him completely – and have every reason to do so. He has felt for a long time that the System has rather overshadowed my own life and would like to do a fuller book on me as a person.

It is a chance for my own self to surface a little rather than be lost in the system. I rather see it as a lifebelt against being drowned and it is terribly important to me – and this was brought home to me when I was showing the boys the albums – to remember these things which are me.

She then went on to ask her father to supply the family albums for the book and, hey presto, a few days later several large, red, gold-embossed family albums made their way to the South London offices of my publisher. A number of photographs were selected and duplicated, and the albums returned. The Princess herself helped to identify many of the people who appeared in the photographs with her, a process she greatly enjoyed as it brought back many happy memories, particularly of her teenage years.

She appreciated, too, that, in order to make the book truly distinctive, we had to have a previously unpublished jacket picture. As it was out of the question that she could attend a photo shoot, she personally chose and supplied the winsome Patrick Demarchelier cover photograph, which was one she kept in her study desk at Kensington Palace. This shot, and those of her and her children, which were used inside, were her particular favourites. We have chosen a hitherto unseen Demarchelier shot for the cover of this anniversary edition of Diana: Her True Story – In Her Own Words.

These were quiet interludes as the storm clouds gathered. The book was due to be published on 16 June 1992 and, as that date approached, the tension at Kensington Palace became palpable. Her newly appointed private secretary, Patrick Jephson, described the atmosphere as ‘like watching a slowly spreading pool of blood seeping from under a locked door’. In January 1992 she was warned that Buckingham Palace was aware of her co-operation with the book, even though at that stage they did not know its contents. Nonetheless she remained steadfast in her involvement with the venture. She knew that there was a cataclysm in the offing but had no doubts that she would survive it.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (June 27, 2017)

- Length: 448 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501169731

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Diana Trade Paperback 9781501169731