LIST PRICE $7.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

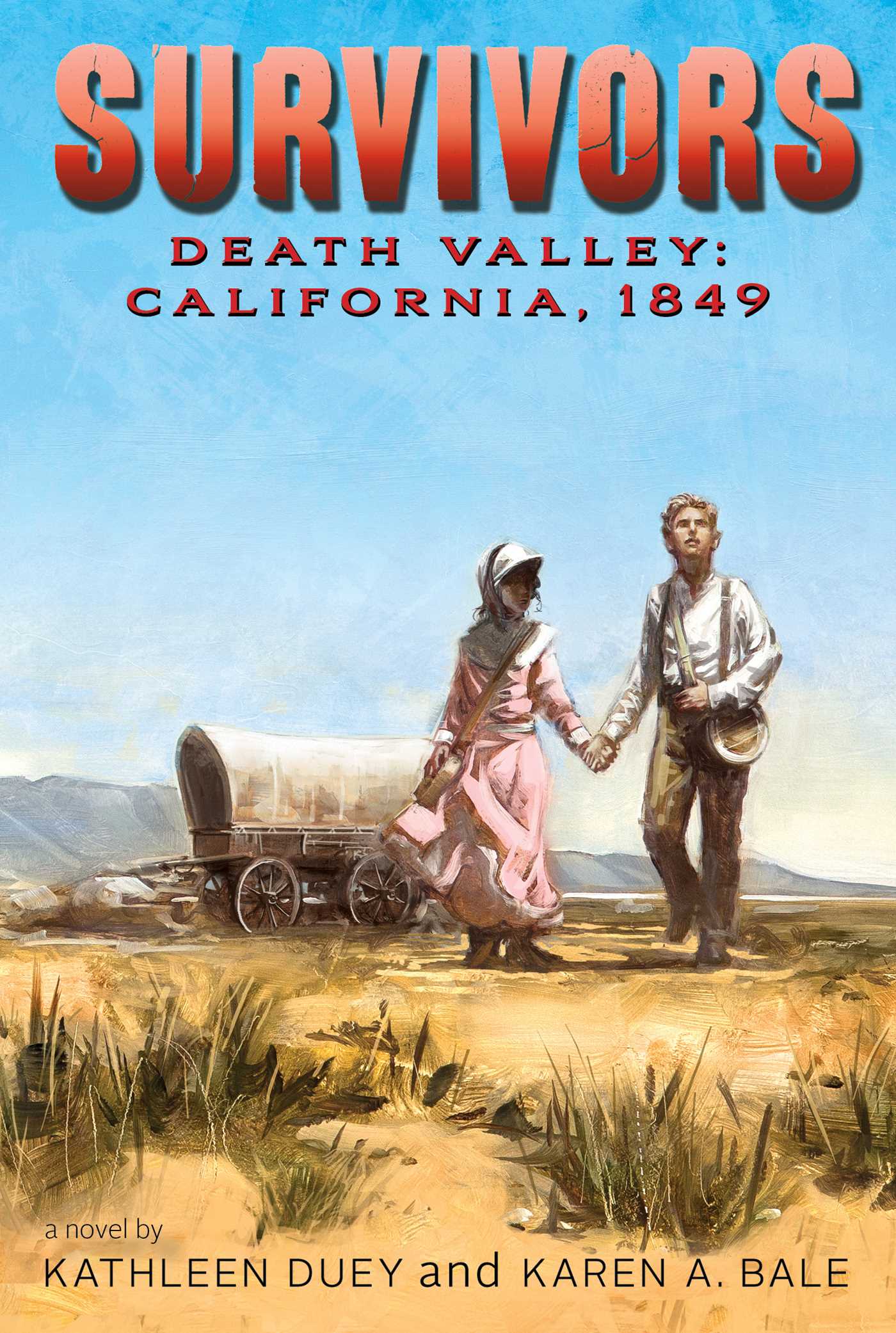

A brother and sister struggle to survive a harrowing trip across Death Valley—the most dangerous part of the Mojave Desert and the hottest spot in North America—in this riveting tale of historical fiction, part of the Survivors series.

California, 1849: Jess, Will, and their father are in grave danger—separated from the rest of their west-bound party, their wagon is useless with a broken axle, and Pa is seriously ill from an injury that Will feels is his fault.

In a valiant attempt to save their family, Will and Jess set off on foot over the endless sands to find help. Each day of their journey brings a new peril, but nothing more frightening than the constant, overpowering thirst that muddles their minds and threatens their very will to survive. With so much at stake, can Will and Jess win their desperate battle with the unrelenting desert?

California, 1849: Jess, Will, and their father are in grave danger—separated from the rest of their west-bound party, their wagon is useless with a broken axle, and Pa is seriously ill from an injury that Will feels is his fault.

In a valiant attempt to save their family, Will and Jess set off on foot over the endless sands to find help. Each day of their journey brings a new peril, but nothing more frightening than the constant, overpowering thirst that muddles their minds and threatens their very will to survive. With so much at stake, can Will and Jess win their desperate battle with the unrelenting desert?

Excerpt

Death Valley Chapter One

Will was tired. He glanced at his father. How much farther were they going to walk? There was no game here. There hadn’t been so much as a rabbit for three days. He shouldered his rifle. “Why don’t we just go back to camp, Pa?”

His father turned, tugging his hat brim lower. “Your mother and sister can’t go much longer without meat. Nor Eli, nor Jeb.”

“Van Patten’s brindled ox is about to die, anyway, Pa. Jess told me they’re saying they’ll still share—”

“I don’t like depending on anyone’s charity, Will.”

Will pressed his lips together to keep from saying what was on his mind. If they had stayed in Illinois, if his father’s dreams of California gold hadn’t interfered with his good judgment, they would all be sitting around the hearth, stringing popcorn for the Christmas tree. Outside the windows would be snow on the ground, solid and white.

“Over there, Will.”

Will followed his father’s gesture. There were sparse clumps of sage growing from the rocky soil. As he stared, Will thought he saw the leaves vibrate. Something was crouched between the stalks, hiding. Will felt his mouth water, imagining rabbit stew.

“I’ll get around to the side, Will. I’ll flush it out toward you.”

Will nodded without looking away from the wind-beaten sage. His father’s boots ground against the rocky soil. There was no way to move silently here. The howling winter winds had scoured the topsoil, exposing a layer of gravel.

“Watch carefully,” Will’s father said quietly. “If it makes a run back this way, call out. Maybe I can get a shot at it.”

Will glanced up, then his eyes returned to the sage. His father walked closer, as intent as any mountain lion, knees bent, his rifle half raised. Will said a little prayer and raised his own rifle. They had almost used up the bags of flour and rice they’d bought from the Mormon storekeep in the new little settlement on Salt Lake.

Will held the rifle steady, breathing evenly, waiting. Without meaning to, he pictured their old kitchen table, the one they’d left beside the trail a few weeks out of Fort Laramie the first time they had had to lighten the wagon. It felt like their lives were scattered behind them all the way back to Illinois. Most of their furniture was gone; they had traded his mother’s trunk for new iron tires on the wagon wheels.

Will glanced at his father—he was slowly advancing on the clump of sage. Will allowed himself to think about what a real supper would be like. He could see it so clearly, smell the inviting scents of his mother’s chicken and dumplings, her fruit pies, steamed sweet corn and yams. His mouth flooded with saliva again.

“Will!”

He jerked his head up to look at his father.

“Is it still in there? Did you see it run?”

Will shook his head, pretty sure he hadn’t actually closed his eyes. He was so tired. They hadn’t had enough water for days—or enough food, really, even though the families were sharing meat whenever anyone had to kill one of the oxen.

The sage shook suddenly, and Will pulled the hammer all the way back, waiting tensely. Then he settled the rifle snug into his shoulder and aimed at the blur of motion that burst clear a second later. Steady, deliberate, he pulled the trigger.

“You got him! He’s a big one,” Will’s father called, holding the rabbit up by one hind leg.

Will smiled, tapping powder into his rifle. He rammed the shot home, then slid the rod back into its scabbard, reaching for the pouch that held his percussion caps.

Following his father’s impatient gesture, he began to wade through the scrubby line of sage where the rabbit had hidden. There was a sudden scrabbling sound, and two more rabbits burst out of the brush. Lifting the rifle, he killed the first rabbit. The second ran on as he stopped to reload.

“I’ll get it,” Pa yelled, and broke into a run. Will heard the shot and his father’s jubilant shout. He smiled. So there would be three rabbits for supper. Ma wouldn’t have to ladle carefully to make sure there was a fair share of the meat in everyone’s broth. Tonight, there would be plenty.

“We’ll gut and skin these here, son,” Pa called.

Will started toward him. All the men had taken to cleaning their game outside camp. It saved the families with less food the torture of watching a long supper preparation. The Hogans were the worst off. Will hated bringing meat into camp, walking past their wagon. They had seven children, and Mr. Hogan was a terrible shot. Back home, he had been a fine farmer, always helping his neighbors in bad years. All the Van Pattens still gave him meat because of that. Otherwise, his children would have starved by now.

For the last month there had been little game to share. Mr. Bailey kept all his meat for himself. Mr. Tolford still gave away some, mostly to the Hogans, but he jerked more meat now and kept it back for himself and Moses, his hired man. They were both good shots. Mr. Tolford’s wagons were full of supplies, not bedding and furniture. He had even brought oats for his mule team.

“Gather up some sage, Will.” Pa leaned his rifle against a flat rock the size of a bedstead, then pulled his slender skinning knife from its scabbard.

“Yes, sir.” Will propped his rifle beside his father’s and laid the rabbits on the rock. Then he headed toward the brush.

The sage stems were hollow and dry and snapped easily. The sharp, clean smell of the leaves tickled at Will’s nostrils. When he started back, his father was just finishing the first rabbit. Will spread the sage out so his father could lay the carcass down, pink and glistening, then set the skin to one side. Will broke off a handful of leaves and rubbed them over the still warm meat. It was early, but flies would gather soon.

“Your mother will be glad to see these,” Will’s father said as he gutted the second rabbit, then made the long, quick cuts that freed the skin.

A faint rustling caught Will’s attention. He half-turned, one hand full of sage leaves. Twenty paces away, among the dense papery leaves of a buckwheat bush, he saw a slight movement. Suddenly, a big jackrabbit, twice the size of the cottontails they had killed, rushed into the open.

Whirling, leaning to reach across the rock for his rifle, Will had a split-second daydream of a dramatic, last-second shot, of being the one to bring home enough meat to last into tomorrow. Then he stepped on a rock that rolled beneath his foot. He struggled to keep his balance as he lurched sideways, falling into his father. As he hit the ground he heard his father cry out.

Will scrambled to his feet. His father’s face had gone pale, and the knife lay at the base of the rock. There was a slanting gash across his father’s thigh.

“What the—? Will, what are you doing?” Pa bent to press his hand over the wound.

Will stood still, shocked by the stream of blood pouring from between his father’s fingers. “I was just—I saw a jackrabbit and I was just—”

“Tear some strips from your shirt, Will. Two or three, wide enough to cover this.”

Will stared at his father for a second, still stunned by the ivory pallor in his face, the sheen of sweat on his skin.

“Do as I say, Will!”

Will fumbled at his shirttail, his hands shaking. It had all happened so fast. He shrugged his shirt off, then gripped the cloth, hesitating an instant. His entire life it had been drilled into him to take care of the clothing that had cost his mother so many hours to sew. And she sewed well. The hem was sturdy, the stitches so close together that for an eternal moment Will could not manage to start a tear. Clumsy, frantic, glancing involuntarily at the blood soaking his father’s trousers, Will managed to rip a long strip of cloth and extended it toward his father.

“I can’t. You’ll have to do it, Will.” Pa’s voice sounded distant, faint. He worked at his suspenders buttons and slid his trousers down. The cut was even deeper than Will had thought. Frightened, Will tore two more bandage strips. He forced himself to concentrate, to push the edges of the gash together, to bind his father’s leg tightly. The blood soaked the bandages almost instantly, but once they were tied off, it slowed to a trickle. Pa pulled his trousers up and fastened his suspenders again.

“Finish skinning that last rabbit, son.”

Will looked up at the calmness in his father’s voice. “I’m sorry, Pa. I’m really sorry. I just thought—”

“We don’t have time for that now, Will. Finish the last one, and let’s get going.”

“Can you walk, Pa?”

His father laughed, an ugly grating sound. “Unless you’re going to carry me.”

Will was tired. He glanced at his father. How much farther were they going to walk? There was no game here. There hadn’t been so much as a rabbit for three days. He shouldered his rifle. “Why don’t we just go back to camp, Pa?”

His father turned, tugging his hat brim lower. “Your mother and sister can’t go much longer without meat. Nor Eli, nor Jeb.”

“Van Patten’s brindled ox is about to die, anyway, Pa. Jess told me they’re saying they’ll still share—”

“I don’t like depending on anyone’s charity, Will.”

Will pressed his lips together to keep from saying what was on his mind. If they had stayed in Illinois, if his father’s dreams of California gold hadn’t interfered with his good judgment, they would all be sitting around the hearth, stringing popcorn for the Christmas tree. Outside the windows would be snow on the ground, solid and white.

“Over there, Will.”

Will followed his father’s gesture. There were sparse clumps of sage growing from the rocky soil. As he stared, Will thought he saw the leaves vibrate. Something was crouched between the stalks, hiding. Will felt his mouth water, imagining rabbit stew.

“I’ll get around to the side, Will. I’ll flush it out toward you.”

Will nodded without looking away from the wind-beaten sage. His father’s boots ground against the rocky soil. There was no way to move silently here. The howling winter winds had scoured the topsoil, exposing a layer of gravel.

“Watch carefully,” Will’s father said quietly. “If it makes a run back this way, call out. Maybe I can get a shot at it.”

Will glanced up, then his eyes returned to the sage. His father walked closer, as intent as any mountain lion, knees bent, his rifle half raised. Will said a little prayer and raised his own rifle. They had almost used up the bags of flour and rice they’d bought from the Mormon storekeep in the new little settlement on Salt Lake.

Will held the rifle steady, breathing evenly, waiting. Without meaning to, he pictured their old kitchen table, the one they’d left beside the trail a few weeks out of Fort Laramie the first time they had had to lighten the wagon. It felt like their lives were scattered behind them all the way back to Illinois. Most of their furniture was gone; they had traded his mother’s trunk for new iron tires on the wagon wheels.

Will glanced at his father—he was slowly advancing on the clump of sage. Will allowed himself to think about what a real supper would be like. He could see it so clearly, smell the inviting scents of his mother’s chicken and dumplings, her fruit pies, steamed sweet corn and yams. His mouth flooded with saliva again.

“Will!”

He jerked his head up to look at his father.

“Is it still in there? Did you see it run?”

Will shook his head, pretty sure he hadn’t actually closed his eyes. He was so tired. They hadn’t had enough water for days—or enough food, really, even though the families were sharing meat whenever anyone had to kill one of the oxen.

The sage shook suddenly, and Will pulled the hammer all the way back, waiting tensely. Then he settled the rifle snug into his shoulder and aimed at the blur of motion that burst clear a second later. Steady, deliberate, he pulled the trigger.

“You got him! He’s a big one,” Will’s father called, holding the rabbit up by one hind leg.

Will smiled, tapping powder into his rifle. He rammed the shot home, then slid the rod back into its scabbard, reaching for the pouch that held his percussion caps.

Following his father’s impatient gesture, he began to wade through the scrubby line of sage where the rabbit had hidden. There was a sudden scrabbling sound, and two more rabbits burst out of the brush. Lifting the rifle, he killed the first rabbit. The second ran on as he stopped to reload.

“I’ll get it,” Pa yelled, and broke into a run. Will heard the shot and his father’s jubilant shout. He smiled. So there would be three rabbits for supper. Ma wouldn’t have to ladle carefully to make sure there was a fair share of the meat in everyone’s broth. Tonight, there would be plenty.

“We’ll gut and skin these here, son,” Pa called.

Will started toward him. All the men had taken to cleaning their game outside camp. It saved the families with less food the torture of watching a long supper preparation. The Hogans were the worst off. Will hated bringing meat into camp, walking past their wagon. They had seven children, and Mr. Hogan was a terrible shot. Back home, he had been a fine farmer, always helping his neighbors in bad years. All the Van Pattens still gave him meat because of that. Otherwise, his children would have starved by now.

For the last month there had been little game to share. Mr. Bailey kept all his meat for himself. Mr. Tolford still gave away some, mostly to the Hogans, but he jerked more meat now and kept it back for himself and Moses, his hired man. They were both good shots. Mr. Tolford’s wagons were full of supplies, not bedding and furniture. He had even brought oats for his mule team.

“Gather up some sage, Will.” Pa leaned his rifle against a flat rock the size of a bedstead, then pulled his slender skinning knife from its scabbard.

“Yes, sir.” Will propped his rifle beside his father’s and laid the rabbits on the rock. Then he headed toward the brush.

The sage stems were hollow and dry and snapped easily. The sharp, clean smell of the leaves tickled at Will’s nostrils. When he started back, his father was just finishing the first rabbit. Will spread the sage out so his father could lay the carcass down, pink and glistening, then set the skin to one side. Will broke off a handful of leaves and rubbed them over the still warm meat. It was early, but flies would gather soon.

“Your mother will be glad to see these,” Will’s father said as he gutted the second rabbit, then made the long, quick cuts that freed the skin.

A faint rustling caught Will’s attention. He half-turned, one hand full of sage leaves. Twenty paces away, among the dense papery leaves of a buckwheat bush, he saw a slight movement. Suddenly, a big jackrabbit, twice the size of the cottontails they had killed, rushed into the open.

Whirling, leaning to reach across the rock for his rifle, Will had a split-second daydream of a dramatic, last-second shot, of being the one to bring home enough meat to last into tomorrow. Then he stepped on a rock that rolled beneath his foot. He struggled to keep his balance as he lurched sideways, falling into his father. As he hit the ground he heard his father cry out.

Will scrambled to his feet. His father’s face had gone pale, and the knife lay at the base of the rock. There was a slanting gash across his father’s thigh.

“What the—? Will, what are you doing?” Pa bent to press his hand over the wound.

Will stood still, shocked by the stream of blood pouring from between his father’s fingers. “I was just—I saw a jackrabbit and I was just—”

“Tear some strips from your shirt, Will. Two or three, wide enough to cover this.”

Will stared at his father for a second, still stunned by the ivory pallor in his face, the sheen of sweat on his skin.

“Do as I say, Will!”

Will fumbled at his shirttail, his hands shaking. It had all happened so fast. He shrugged his shirt off, then gripped the cloth, hesitating an instant. His entire life it had been drilled into him to take care of the clothing that had cost his mother so many hours to sew. And she sewed well. The hem was sturdy, the stitches so close together that for an eternal moment Will could not manage to start a tear. Clumsy, frantic, glancing involuntarily at the blood soaking his father’s trousers, Will managed to rip a long strip of cloth and extended it toward his father.

“I can’t. You’ll have to do it, Will.” Pa’s voice sounded distant, faint. He worked at his suspenders buttons and slid his trousers down. The cut was even deeper than Will had thought. Frightened, Will tore two more bandage strips. He forced himself to concentrate, to push the edges of the gash together, to bind his father’s leg tightly. The blood soaked the bandages almost instantly, but once they were tied off, it slowed to a trickle. Pa pulled his trousers up and fastened his suspenders again.

“Finish skinning that last rabbit, son.”

Will looked up at the calmness in his father’s voice. “I’m sorry, Pa. I’m really sorry. I just thought—”

“We don’t have time for that now, Will. Finish the last one, and let’s get going.”

“Can you walk, Pa?”

His father laughed, an ugly grating sound. “Unless you’re going to carry me.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (July 7, 2015)

- Length: 176 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481431262

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 720L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Death Valley Trade Paperback 9781481431262

- Author Photo (jpg): Kathleen Duey Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit