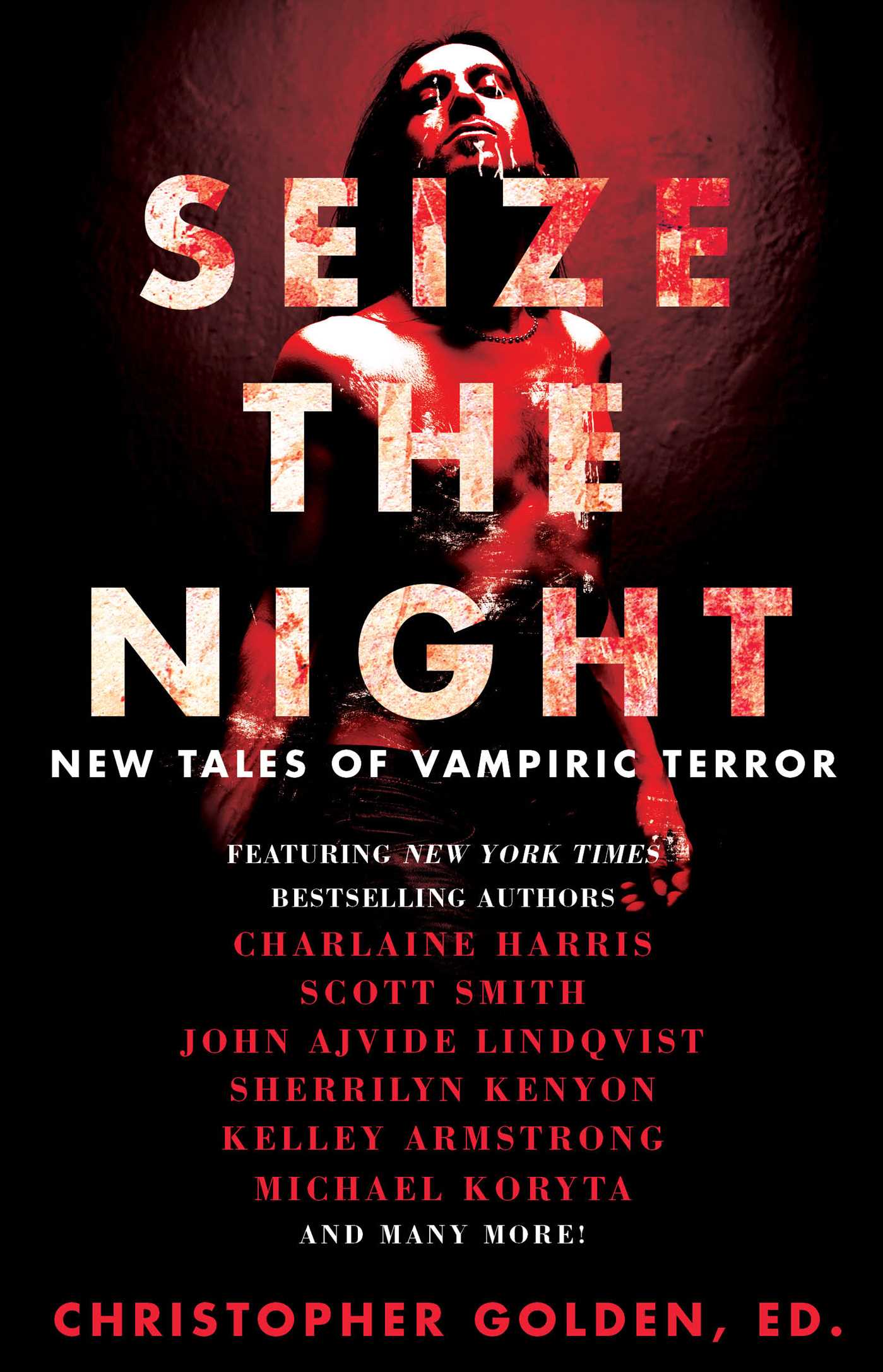

Seize the Night

New Tales of Vampiric Terror

By Kelley Armstrong, John Ajvide Lindqvist, Laird Barron, Gary A. Braunbeck, Dana Cameron, Dan Chaon, Lynda Barry, Charlaine Harris, Brian Keene, Sherrilyn Kenyon, Michael Koryta, John Langan, Tim Lebbon, Seanan McGuire, Joe McKinney, Leigh Perry, Robert Shearman, Scott Smith, Lucy A. Snyder, David Wellington and Rio Youers

Edited by Christopher Golden

LIST PRICE $18.00

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

A blockbuster anthology of original, blood-curdling vampire fiction from New York Times bestselling and award-winning authors, including Charlaine Harris, whose novels were adapted into HBO’s hit show True Blood, and Scott Smith, publishing his first work since The Ruins.

Before being transformed into romantic heroes and soft, emotional antiheroes, vampires were figures of overwhelming terror. Now, from some of the biggest names in horror and dark fiction, comes this stellar collection of short stories that make vampires frightening once again. Edited by New York Times bestselling author Christopher Golden and featuring all-new stories from such contributors as Charlaine Harris, John Ajvide Lindqvist, Scott Smith, Sherrilyn Kenyon, Michael Kortya, Kelley Armstrong, Brian Keene, David Wellington, Seanan McGuire, and Tim Lebbon, Seize the Night is old-school vampire fiction at its finest.

Before being transformed into romantic heroes and soft, emotional antiheroes, vampires were figures of overwhelming terror. Now, from some of the biggest names in horror and dark fiction, comes this stellar collection of short stories that make vampires frightening once again. Edited by New York Times bestselling author Christopher Golden and featuring all-new stories from such contributors as Charlaine Harris, John Ajvide Lindqvist, Scott Smith, Sherrilyn Kenyon, Michael Kortya, Kelley Armstrong, Brian Keene, David Wellington, Seanan McGuire, and Tim Lebbon, Seize the Night is old-school vampire fiction at its finest.

Excerpt

Seize the Night UP IN OLD VERMONT SCOTT SMITH

The first time he asked, Ally had been there only a few months, and the idea seemed sweet but absurd—so much the latter, in fact, that she wondered if the old man might not be just as befuddled as his wife; it was easy for Ally to say no. She was happy for a change, still newly arrived in Huntington (new town, new job, new boyfriend), and feeling cocky with all the high hopes attendant to such beginnings. It was early autumn in the Berkshires—the first slaps of color appearing in the trees alongside the road, the morning light so clear it hit her eyes like cold water from a pump. Ally had dyed her long hair blond the previous summer; she’d taken up running and had grown ropy with the exercise, the veins standing out on her arms, dark blue beneath the skin. She felt good about herself after a long period where quite the opposite had been true; she was even beginning to think that maybe, if she could just keep her head straight here, her years of wandering—all those false starts and wrong turns—might at last be behind her. She wanted to believe this: that she’d finally found herself a home.

Even after she learned their names, Ally thought of the couple as “the Hobbits.” They were short and stout and friendly, essential qualities that their advanced age seemed only to have heightened. The woman’s name was Eleanor. She had Alzheimer’s, and her condition had deteriorated to the point where she could no longer remember her husband’s name. Eleanor called him Edward, or Ed, or even Big Ed—someone from her distant past, Stan explained to Ally, though he didn’t know who. It didn’t seem to bother him. “If she liked the man, that’s good enough for me,” he said, and he happily responded to the name. They both had thick white hair and oddly large hands, and their skin was noticeably ruddy, as if they spent a great deal of their time outdoors. When they dressed in matching sweaters—which they often did—they could look so much alike that Ally would find herself thinking of them as brother and sister rather than husband and wife.

The second time Stan asked, it was deep winter. If Ally had said no the first time out of an excess of optimism, she did so on this subsequent occasion from an utter deficit. She was fairly certain that her boyfriend was sleeping with her roommate, though she hadn’t caught them yet—this wouldn’t happen for another month or so. She was cold all the time; business was slack at the diner; she had a yeast infection that kept reasserting itself each time she imagined it finally cured. She felt bored and poor and unhappy enough that she would’ve liked to crawl out of her own skin, if such a thing were possible. She couldn’t see how anyone would want anything to do with her—even this sad, lonely couple. So when Stan repeated his invitation, she just smiled and said no again. It was more difficult to decline this time around, however: after the Hobbits departed, Ally went into the diner’s restroom and wept, sobbing as vigorously as she had since childhood, running both faucets and the electric hand dryer in an attempt to mask the sound of her distress. It was the sight of Stan helping Eleanor to their car that had prompted this outburst, his hand under her elbow as he guided her across the icy lot—it was the years of love implicit in the gesture, along with Ally’s sudden, self-pitying certainty that she herself would never feel a touch so tender.

The Hobbits ate a late lunch in the diner toward the end of every month, stopping on their way down from Vermont before they turned east for Boston, where Eleanor had appointments with various specialists—“Hopes raised and hopes dashed,” was how Stan described the expeditions. He’d order a grilled cheese sandwich for Eleanor—American cheese, white bread, the purest sort of comfort food—and New England clam chowder for himself. He’d drink a cup of coffee; Eleanor would quickly drain a vanilla shake through its long straw, rocking back and forth with childlike pleasure. If it was quiet, as it often was in those late afternoon hours, Ally would pull up a chair beside their booth and chat with them while they ate. Eleanor called Ally Reba, which Stan assured her was the highest sort of compliment: Reba had been Eleanor’s college roommate. A beautiful girl, Stan said, smart and funny and more than a little impish, dead now for forty years, one of the first friends they’d lost, so sad, breast cancer, with three young children left behind, but what a pleasure now to find her resurrected so unexpectedly in Ally. Eleanor continued to suck contentedly at her milkshake, swaying to her internal music, while Stan spoke in this manner. She rarely ate more than a bite or two of her sandwich, and sometimes, after they departed, Ally would stand in the kitchen and quickly devour the rest. All that winter, with each successive day seeming darker and colder than the last, she felt an incessant hunger. By March, she’d gained twenty pounds. Her waitressing uniform had grown snug around her midsection and rear, making her feel like an overstuffed sausage.

It was late April when Stan asked the third time, and as soon as Ally heard the words, she realized she’d been waiting for them, hoping he might try again. By this point, Ally’s boyfriend had moved to Springfield with her roommate. Ally was behind on her rent and lonely enough that she’d begun to drift into the diner on her evenings off—a new low. She knew she couldn’t stay in Huntington much longer, but she had no idea where to go instead. She’d just turned thirty-three, and she sensed this was far too old to be living in such a rootless, aimless manner. She wasn’t so desperate that she imagined the Hobbits might save her, but why shouldn’t they be able to offer a brief reprieve, a little space in which she might lick her wounds?

She and Stan quickly agreed upon an arrangement: room and board, plus what Stan called “a small weekly stipend,” which was nonetheless nearly equal to what Ally had been taking home from the diner. And in exchange? Some cooking and cleaning, a little light weeding in the garden, the occasional trip into town to pick up groceries or Eleanor’s medications, but mostly just the pleasure of Ally’s company—“Eleanor likes you,” Stan said. “You calm her. Merely having you in the house will make her days so much easier.”

The Hobbits picked her up outside the diner three days later, on their way back from Boston. Ally had two suitcases and a large cardboard box, which they loaded into the Volvo’s deep trunk.

Then they started north.

It was the sort of early April afternoon that can throw a line into summer, with pockets of dirty snow still melting in the hollows but the day suddenly hot and thick, the world seeming to hold its breath as dark gray clouds mass in the west, an errant July thunderstorm, arriving three months too early. The air inside the Volvo was stuffy; it smelled of cherry cough drops. Before they’d even made it out of town, Ally began to feel carsick. Her stomach gave a queasy swing with every turn. She started to count upward by sevens, a calming exercise a stranger had taught her once, during a cross-country bus trip, when Ally was heading back east from Reno. She’d been working as a barmaid in a second-tier casino: another lost job, another failed relationship, another aborted attempt to make a life. This had been almost a decade ago, and Ally remembered how ancient the stranger on the bus had seemed, so ill used and depleted, though the woman couldn’t have been much older than Ally was now. Seven, fourteen, twenty-one, twenty-eight . . . Ally was at eighty-four when Stan glanced back from the front seat, asking if she minded music. Ally shook her head, shut her eyes, feeling abruptly tired, almost drugged. A moment later, a Beatles song began to play: “Hey Jude.” She was asleep before the first chorus, dropping into a tropical dream, to match the oddly tropical weather. Ally was on a sailboat in the Caribbean, where she’d never been, and Mrs. Henderson, her high school gym teacher, was trying to teach her how to tie nautical knots, with mounting impatience—mounting urgency, too—because a storm was rising, seemingly out of nowhere; one moment the sky was clear, the sea calm and sun-splashed, and the next, rain was sweeping across the deck, the boat pitching, the wind seeming to rage through the rigging, sounding tormented, howling, shrieking, a pure cry of animal pain, so loud that Mrs. Henderson had to shout to be heard, and Ally couldn’t follow her instructions, which meant they were doomed—Ally somehow understood this, that if she couldn’t learn the necessary knots, the boat would surely founder. She awakened as the first wave broke over the deck, opening her eyes to a changed world, her dream panic still gripping her. Rain was running down the car’s windows, blurring the view beyond the glass, the trees seeming too close to the road (murky, animate, swaying in the storm’s onslaught), the car swaying, too, rocking and thumping over the deep ruts of a narrow lane—no, not a lane, a driveway—and now the trees were parting before them and the Volvo was splashing through one final pothole, deeper and wider than the others, moatlike, the car almost bottoming out before emerging into a clearing, a large irregularly shaped circle of muddy grass, on the far side of which stood a tall, narrow house. The house looked gray in the rain and fading light, though somehow Ally could tell it was really white. The movement of the surrounding trees lent the house a sense of motion, too; the structure seemed to rock in counterpoint to the plunging branches. Beyond the house, Ally could just make out a small barn. Beyond the barn, a steep—almost sheer—pine-covered hill rose abruptly skyward. Stan put the car in park and turned off the engine, and for a long moment the three of them just sat there, waiting for the rain to slacken enough so that they might dash across the lawn and enter the house. Ally could hear “Hey Jude” still playing, though there was something odd about it now—the speed was off, the pitch, too. It took her a handful of seconds to realize that it wasn’t the CD; it was Eleanor softly singing in the front seat, her voice as high as a child’s and so out of tune that it sounded intentional, as if the old woman might have been mocking the Beatles’ lyrics.

Remember to let her under your skin . . .

This was Ally’s nadir, what would be the lowest dip of her spirits for a long time to come. She realized she didn’t know these people, not really—not at all—and that no one she actually did know had any idea where she was; even she didn’t know where she was, just Vermont, northern Vermont, somewhere east of Burlington, in the rain, at the base of a hill that looked too steep to climb . . . yes, she’d made a terrible mistake. She thought briefly of fleeing, pushing open the Volvo’s door and darting off into the storm, beneath the swaying trees, through the mud and wind. She could make her way back down the drive to whatever road might lay at its end; she could put her hope in the prospect of a passing car, a stranger’s kindness. She’d hitch a ride to the nearest town, where she’d make a collect call to . . . whom, exactly? Ally was picturing her ex-roommate and her ex-boyfriend, the two lovers just sitting down to an early dinner in Springfield, the phone starting to ring, one of them rising, reaching to pick up the receiver—Ally felt her face flush at the thought, the shame she’d feel as she announced herself, as she extended her hand for their assistance, their pity—and at that precise moment the rain stopped. It didn’t slacken or abate; it just ceased—the wind did, too. The world seemed so silent in the storm’s wake that Ally experienced the sudden quiet as its own sort of noise, loud and unsettling. Stan shifted in his seat, turned to look at Eleanor. “Well, love,” he said. “Shall we?”

“Is Reba staying for supper?”

Stan glanced at Ally in the rearview mirror, gave her a smile of playful complicity; it was growing familiar now, this smile—a cherub peeking out from behind a rose-tinted cloud. “What do you think, Reba? Would you like to stay for supper?”

And as easily as that, everything was okay again. The idea of fleeing through the trees seemed suddenly absurd; it was already being forgotten. Ally smiled back at the old man, smiled and nodded: “Yes, Stan,” she said. “That would be lovely.”

When Eleanor’s condition first began to reveal itself, Stan had moved their bedroom to the house’s first floor. They rarely ventured upstairs anymore. This meant that Ally would have free run of the entire second story. The evening of her arrival, after a dinner of hot dogs and potato salad, Ally climbed a steep flight of stairs to discover three bedrooms and a large bathroom awaiting her. She hesitated at the first doorway she came to . . . This one? Beyond the threshold was a canopied bed, a mahogany bureau and matching night table, a red-and-white rag rug to complement the red-and-white-striped curtains. Ally heard a creaking sound behind her, and when she turned, she saw her footprints in the dust on the floor—not just her footprints, but paw prints, too, a complicated skein of them trailing up and down the hallway. And then, in the shadows at the far end of the corridor, peering toward her—so big that Ally initially mistook it for a bear—she glimpsed an immense black dog. Ally felt a surge of heat pass through her body: an adrenaline dump. For an instant, she was so frightened that it was difficult to breathe. She could hear the dog audibly sniffing, taking in her scent. Without making a conscious decision to do so, Ally began to retreat, first one slow step, then another. When she reached the head of the stairs, she turned and scampered quickly back down to the first floor.

Stan was still in the kitchen, wiping the counter with a sponge. He turned at her approach, greeted her with one of his cherub’s smiles.

“There’s a dog upstairs,” Ally said.

Stan nodded. “That would be Bo. I hope you’re not allergic?”

“No. I was just . . . I didn’t realize there was a dog in the house.”

“Ah, of course not—I should’ve introduced you. So sorry, my dear. Did he startle you?”

Before Ally could answer, she sensed movement behind her, very close. Bo had followed her downstairs. He pressed his big head against Ally’s right buttock, sniffing again. Ally jumped, let out a yelp, and the dog scrambled backward, nearly losing his footing on the slippery kitchen tiles. Once more, Ally felt herself go hot—this time from embarrassment rather than terror. Up close, there was nothing at all frightening about the animal. Like his aged master and mistress, he was clearly tottering through his final stretch here on earth. His eyes had a gray sheen to them, and his joints seemed so stiff that even his massive size came across as a handicap. There was Great Dane in him, maybe some St. Bernard, too, but Ally’s original perception remained dominant: what Bo resembled most was an ailing, elderly black bear.

“Blind and deaf,” Stan said. “If I had any mercy, I’d put him out to pasture. But he has such a good effect on Eleanor. It will be hard to lose him.”

“He was here by himself? While you were in Boston?”

Stan dismissed Ally’s concern with a flick of his hand. “The doctor comes twice a day when we’re gone. Lets him out. Makes sure he has food and water. Bo doesn’t require much more than that.”

“The doctor?”

“Eleanor’s physician. Dr. Thornton. You’ll meet him soon enough.”

Eleanor’s voice came warbling toward them from the rear of the house, as if by speaking her name, Stan had summoned her: “Ed . . . ?”

Stan reached out, patted Ally’s arm. “Duty calls.” He tossed the sponge into the sink, then turned and started from the room.

“Eddie . . . ?”

“Coming, love!”

Ally clicked off the kitchen light, made her way back upstairs, the dog trailing closely behind her, panting from the effort of the climb. A quick tour of the three available bedrooms convinced Ally that there was nothing to distinguish one above the others, and so, after a trip to the bathroom (she peed, and when she flushed the toilet, it sounded like a malfunctioning jet engine, a high-pitched hydraulic shriek that seemed to shake the entire house), she returned to the first room she’d glimpsed, with its red-and-white curtains: it felt marginally more familiar. Bo had followed her up and down the corridor, standing just beyond each successive threshold as Ally examined the bedrooms, and now, when she tried to shut the door to what she was already thinking of as her room, the dog shuffled forward and pushed it back open with his nose. His head was the size and shape of a basketball; his thick black fur had traces of silver in it. His eyes were as large as a cow’s and slightly protuberant. Ally had to remind herself that he couldn’t see with them, because there was something so alert about the animal—alert and observant. He stood there, front paws inside the room, back paws in the corridor, not watching, not listening, but somehow obviously appraising her.

Ally realized with a lurch that her suitcases and her cardboard box were still in the Volvo’s trunk. She was feeling far too worn out to contemplate unraveling the tangled knot of their retrieval—the trip back downstairs, the hunt for a flashlight to guide her across the dark expanse of muddy lawn, the possibility of finding the Volvo locked, of needing to rouse Stan to ask for his assistance—so she took the path of least resistance. She removed her clothes and climbed beneath the musty-smelling sheets. In the morning, she told herself: everything will be resolved in the morning. Then she turned out the light.

For such a large and enfeebled animal, Bo could move with surprising stealth. Ally didn’t hear him approach from the doorway; she just felt the bed shudder as he bumped against it. At first she assumed this was an accident, that he’d simply stumbled against the bed as he blindly crossed the room, but then the mattress kept swaying, the frame making a soft creaking sound, and gradually Ally had to concede that something intentional was happening in the darkness, though she couldn’t guess what it might be. The bed’s persistent rocking began to assume an oddly sexual overtone. It roused a memory for Ally, of her one attempt at hitchhiking: what had appeared to be a perfectly harmless old man had picked her up outside of Los Angeles as she was heading north toward her ill-fated interlude in Reno. She’d fallen asleep a few miles beyond Bakersfield, then awakened sometime later, in the dark of a highway rest stop, slumped against the car’s passenger-side door with the old man pressed against her, thrusting rhythmically. He was still fully clothed, but she could feel his erection, the eager, animal-like insistence of it, prodding at her hip. The old man’s face was only inches away from hers, his eyes clenched shut, his mouth gaping; his breath smelled sharply of bacon. Ally fumbled for the door handle, spilled out of the car, ran off across the parking lot—it all came back to her now, even the smell of bacon—and she pictured Bo attempting a similar assault, clambering on top of her, his thick paws pressing her shoulders to the mattress, pinning her in place, his penis emerging in its bright red sheath . . . she rolled to her right, turned on the bedside lamp, leapt from beneath the sheets.

Poor Bo. He just wanted to climb onto the bed, but he was apparently too ponderous, too aged to manage the feat. He’d lift his left front paw, rest it on the edge of the mattress, then give a feeble sort of jump and try to place the right one beside it, but each time he did this, the left paw would lose its hold and he’d thump back to the floor. He kept repeating the maneuver, without either progress or apparent discouragement: this was what had caused the bed to rock in such a suggestive manner. Ally edged toward him, bent to help haul his heavy body up onto the mattress. Her inclination was to shift rooms—if the dog wanted to sleep on this bed, she’d happily surrender it to him—but then it occurred to her that it might be her company Bo desired. If she changed rooms, it seemed possible that the dog might follow her. She watched him settle onto the mattress, his head coming to rest with an audible sigh on one of the pillows. It was a double bed; there was more than enough room for Ally on the opposite side. So that was where she went: she slid under the sheet and comforter, then reached again to turn out the light.

Darkness.

The mattress tilted in the dog’s direction, weighed down by his bulk. Ally could sense herself sliding toward him. She felt the heat of his body against her bare shoulder, and then, a moment later, his fur: coarse as a man’s beard. His breathing had a strange rhythm, a sequence that started with a small intake of air, followed by a slightly larger one, then an even larger one still, and finally a deep inhalation that seemed to double the size of the dog’s already prodigious body. A dramatic, wheezing exhalation would come at the end of this, filling the entire room for an instant with the meaty stench of Bo’s breath. Then the dog would start all over again, right back at the beginning.

Ally thought of the stale hot dog buns they’d eaten with dinner, the slightly brownish tint to the water emerging from the bathroom’s faucet, the layer of dust that covered everything on the house’s second story—thick as peach fuzz. She thought of the disquieting sensation that the hill beyond the barn had given her when they first pulled into the yard, its looming quality, like a wave about to break. She thought of Eleanor’s voice, so high-pitched and out of tune, with its undertone of mockery, as the old woman sang “Hey Jude.” And while Ally’s mind moved in such a manner, Bo kept inhaling, inhaling, inhaling, and then, with that long, raspy sigh, immersing her in his smell.

It’s okay, Ally said to herself. I’m okay.

And it was true: she’d been in far worse places in her life. She’d slept with a friend in the friend’s van for a week, parked in the East Village, August in New York, the temperature hitting ninety each afternoon, but the windows of the van kept shut because Ally’s friend was certain they’d be robbed, raped, and murdered in their sleep if they so much as cracked one open. She’d squatted with a boyfriend in an abandoned house in Bucks County one spring—no electricity, no heat—the basement ankle-deep with sewage from the overflowing septic system, their own waste rising implacably toward them with each flush of the toilet, a perfect metaphor for their relationship, as the boyfriend had told Ally on the morning he left for good. Nothing here could compare to any of that.

Everything’s going to be okay.

It was with this final thought—a reassuring pat to her own head—that Ally at long last slipped into sleep.

And, for a while, everything was indeed okay.

Ally settled into an easy routine with the Hobbits. On most days, the entire household rose early, shortly after dawn. Ally would help Stan with the breakfast—cold cereal and milk, slices of jam-smeared toast, glasses of orange juice and mugs of coffee. Afterward, she’d wash the dishes, sweep the kitchen floor, tidy up the Hobbits’ already tidy bedroom. Then she’d drive the Volvo down into town and fetch whatever needed picking up that day: Eleanor’s pills from the pharmacy, a bag of groceries from the local Stop & Shop. It was a beautiful little town, with houses arrayed around a central green. The houses were old and postcard pretty: white clapboard with black shutters. There was a Civil War memorial in one corner of the green, a marble soldier standing at attention with a rifle slung over his shoulder. A century and a half’s worth of Vermont winters had worn the young man’s face almost blank, reducing his expression to a ghostly version of Munch’s famous Scream. It was the one unsettling note in an otherwise uniformly serene setting, and often Ally would find herself taking the long way around the green as she ran her errands, simply to avoid glimpsing the statue’s frozen expression of anguish.

Stan had converted the old barn on the Hobbits’ property into an aviary. There were a dozen parakeets inside, and an African gray parrot. Only the parrot could speak, and even he possessed just a limited vocabulary. Mostly, he simply shrieked: “Ed!” Or: “Big Ed!” Or: “Eddie!” Sometimes he’d cry out, quite clearly: “It’s raining, it’s pouring!” But this had nothing to do with the actual weather. One afternoon Ally heard him shouting, in a disconcertingly deep voice: “You liar . . . ! You liar . . . ! You fucking liar . . . !” Eleanor spent most of her mornings in the barn, sitting on a folding lawn chair. There was netting over the building’s entrance, so if the weather was warm enough, Stan could roll back the big wooden door. All of the birds seemed to enjoy this event; they’d swoop and hop and glide from perch to perch, filling the barn with their cries of pleasure. Eleanor would sit in their midst, watching their antics with a serene expression. Stan and Ally could leave her there unattended for hours. Often, Stan would set her up in her chair, then go and work in the garden. Sometimes the parrot would scream “Ed!” And Stan would call back “Yes, dear?” Then the bird would make an eerie cackling sound, something almost like laughter, but also not like laughter at all.

The house was really two houses: a relatively modern structure built around the shell of a much older one. The original house had two low-ceilinged rooms and a deep root cellar. At some point, the Hobbits’ present bedroom, the kitchen, a sunroom, and a mudroom had been added onto the first floor, along with the entire second story. Ally disliked the two older rooms; they felt claustrophobic and depressing, with their flagstone floors—cold and slightly damp to the touch, even on the warmest of days—and their tiny porthole-like windows. But it was the root cellar that truly unsettled her. Stan stored jars of preserves and pickles in its darkness, and Ally dreaded her trips down the ladder-like flight of stairs to retrieve them. For some reason, the space had never been wired with electricity, so you had to bring a flashlight with you. There was an earthen floor, walls of raw stone. It was a tiny space, but large enough so that the flashlight never managed to illuminate all of it at once; there was always one corner or another left in shadow. You entered through a heavy trapdoor in the mudroom’s floor, and once, while Ally was crouched in front of the shelves of preserves, searching for a jar of blackberry jam, Eleanor swung this door shut. Ally scraped her shin in her scramble back up the stairs—she’d been half-certain she wouldn’t be able to force the trapdoor open again, that she’d find herself entombed in the cellar forever. But the trapdoor had lifted free easily enough, and it was Eleanor who ended up screaming, startled by the sight of Ally emerging into the daylight: “Ed!” she cried. “There’s a woman under the floor!”

Dr. Thornton came twice a week to check on Eleanor. He was tall and dark haired and extremely lean—gaunt, even—with deep shadows under his eyes, which made him look much older than he actually was. Ally was astonished to learn that he was only forty-two; she would’ve guessed he was in his midfifties, at least. It wasn’t just his eyes, either, or his slight stoop, or the tentative way he’d approach across the lawn, as if he were testing the solidity of each foothold before committing his full weight to it: he had the personality of an older man, too. Or perhaps a better way to put it would be to say that he had the personality of a man from an older era, an aura of politeness and formality that Ally associated with movies in which men wore frock coats and top hats. It took him weeks to stop calling her “ma’am.” As Stan had promised, though, the doctor was a kind man—consistently good-natured, and full of concern for not only the Hobbits but Ally, too.

When summer arrived with enough vigor to ensure that the roads were consistently mud-free, the doctor began to make his visits on horseback, riding a large bay mare named Molly. He’d tie the horse to an old hitching post in the Hobbits’ yard. Sometimes Ally would walk out and feed Molly carrots straight from the garden, combing the horse’s mane with her fingers while Dr. Thornton chatted to Eleanor and Stan on the far side of the lawn. Everyone enjoyed the doctor’s visits. Eleanor always appeared less anxious on the evenings after he’d come, and Stan tended to be chattier, almost buoyant. Bo liked Dr. Thornton, too: sometimes, when the doctor departed, the dog would follow his horse out of the yard, and Ally would have to jog down the road to fetch him back. Even the birds seemed livelier on the afternoons when the doctor was in attendance. So perhaps it was inevitable that Ally began to feel a similar charge. Sometimes, standing out by the hitching post with Molly, she’d sense the doctor’s eyes upon her—it was a familiar feeling from all her years of waitressing, the weight of a man’s appraising gaze—and she’d think to herself: Why not? He wasn’t married; he lived alone in one of the big white houses facing the village green, seeing patients in an examination room at the building’s rear. A doctor’s wife, Ally thought. It wasn’t a fate she ever would’ve aspired to, but she could see how it might come to feel like a happy ending of sorts, especially in comparison to some of the other paths she’d tried to follow over the preceding years.

Almost from her first day in the house, Ally had resumed her running. She’d head out in the late afternoon, when Eleanor was napping. The roads around the house were hilly, winding, tree lined. It was rare to encounter traffic of any sort. There were only a handful of other residences within running distance. Like the Hobbits’ place, all of these houses had retained their old-fashioned hitching posts. The only horse Ally ever glimpsed was Dr. Thornton’s mare, but sometimes she’d see other animals tied up in the day’s fading light: a weary-looking cow who lifted her head to watch Ally jog past, a spavined donkey, and even an immense goose once, secured to the post with a collar and leash. The bird lifted its wings and honked, frightening Ally, and then kept scolding her till she was out of sight. Perhaps it was simply the company Ally was keeping, but the animals she saw always had an elderly air to them, as if they were shuffling painfully forward through their final days of life. Glimpsing them, Ally would feel her thoughts turn in a melancholy direction. She was happy living with the Hobbits—exceptionally so—perhaps as happy as she’d ever been. But she knew it couldn’t last. Sooner or later, a hard wind would begin to blow through her life, ruining everything. One of these days, Eleanor’s health would take a turn for the worse. And then what? Ally would be left to her own devices once again, which had never served her well. She’d pack up her two suitcases and her cardboard box; she’d step back into the larger world.

And she was right, too. Even as summer reached its height, that wind was approaching. But when it finally arrived, it didn’t come from the direction Ally had anticipated, so it caught her completely by surprise—as hard winds often do.

Because it wasn’t Eleanor who took a turn for the worse.

It was Stan.

All through July, the weather had remained bright and cool, with afternoon breezes rolling down the hillside beyond the barn to sweep across the property. The air smelled of honeysuckle. The scent seemed to energize the parakeets in the aviary—they swooped and sang, darting toward the barn’s open doorway, their tiny, brightly colored bodies ricocheting off the netting. The parrot was affected, too: he roused another phrase from his slumbering vocabulary. “Come back!” he began to yell. “Come back . . . !” Then August arrived, and the breezes vanished. The world turned hot and humid, a moist haze blurring the horizon. There was no more scent of honeysuckle, and in its absence, another, more pungent aroma asserted itself: the yard began to smell tartly of Bo’s urine.

It happened on a Saturday.

Ally was planning to do a load of laundry. She stripped the sheets off her bed, carried them down to the mudroom, where Stan had installed a washing machine years before. Bo shadowed her, as always, then stood at the mudroom’s door, waiting for her to unlatch it. It was shortly after dawn. When Ally followed Bo out into the yard, she could hear the morning chatter of the parakeets. The parrot was awake, too. “Liar!” he called. “Come back . . . !” The barn’s door was still shut. Usually, Stan would’ve already rolled it open for the birds, but Ally hardly registered this uncharacteristic lapse, only recognizing its significance in hindsight. She stood on the grass in her bare feet, watching as Bo’s urine spread into a vast puddle around him. When he turned to come back inside, his paws made a slapping sound through the mud he’d created.

Eleanor was sitting at the kitchen table, waiting for breakfast. She was completely naked. As soon as Ally saw her, she knew. “Eleanor?” she said. “Where’s Stan?”

“Stan?”

“Ed. Where’s Ed?”

“Big Ed won’t get up.”

Ally started for the Hobbits’ bedroom. She was thinking, CPR, trying to remember the proper sequence, the pushes and the breaths—there were more of the one than the other, but how many more? She was thinking, 911, wondering how long an ambulance would take, and where it would even come from, and would she need to give directions, and did she know them. She was thinking: Come back!

But none of this mattered. Ally knew it on the threshold of the room, when she saw Stan lying half in, half out of the bed, his head and shoulder hanging off the edge of the mattress, the fingertips of his right hand touching the floor. She knew it more deeply when she smelled the shit—at first, she assumed this was coming from Bo, who’d followed her in from the kitchen, but then she saw the dark stain on the sheet tangled around Stan’s waist (like a shroud: she actually thought the words). And she knew it for certain when she got close enough to touch the old man, to press her palm against his pale back, his stubbled cheek, his hand—so cold and heavy and strangely plump when she lifted it from the floor.

Ally didn’t cry. She didn’t feel the slightest pull in that direction. It was too shocking for tears.

She did her best to shift Stan back onto the bed. She drew the comforter over him—all the way at first, as she’d seen people do in movies—but then this felt immediately wrong, and she pulled it back down, tucking it under his chin instead. Bo had begun to whimper; Ally herded him from the room. When he kept trying to push his way back in, she grabbed him by his collar and dragged him to the mudroom. She opened the screen door and nudged the dog out into the yard. In the kitchen, Eleanor was still sitting patiently at the table, without any clothes on, waiting for her breakfast to appear before her. Ally fetched a robe for the old woman. It felt good to be in motion, to be accomplishing things that needed doing; it made it easier not to think. She filled a bowl with Cheerios, added a splash of milk, dug a spoon out of the utensil drawer, and set everything on the placemat in front of Eleanor. And then, finally, once Eleanor had started to eat, swaying back and forth, her eyes drifting shut with pleasure, Ally picked up the cordless phone, stepped into the mudroom, and called Dr. Thornton.

After the doctor arrived, after Ally helped Eleanor dress and guided her to her chair in the aviary, after the coroner came, and the men from the funeral home in their black van, after they’d taken the body away, after Ally made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for herself and Eleanor and Dr. Thornton, after Eleanor lay down in the sunroom for her afternoon nap, the doctor and Ally sat together in the kitchen and tried to decide what ought to be done. Could it really be possible that Stan, who’d gone to such lengths to cradle Eleanor while he was alive, had done nothing to ensure her continued care in the event of his death? Dr. Thornton seemed disappointed to discover that Ally had no answer to this question. Was there a place in the house where Stan might’ve kept a will? Ally couldn’t say. Did he ever mention a lawyer? Not as far as Ally could remember. Had he discussed with her, even casually, what his wishes might be, should he predecease Eleanor? Never. The doctor sagged back in his chair. He said that he supposed he should contact the Vermont Agency of Human Services. The idea seemed to depress him. “The problem,” he said, “is that once we do that, we can’t undo it.”

Bo was lying on the floor beneath the kitchen table. He struggled to his feet now, shook himself awake. Then he shuffled toward the mudroom. He wanted to go out, Ally knew; he wanted to piss another puddle onto the lawn. Ally rose and opened the door for him, then stood there, waiting for Bo to find the right spot. He crouched like a female dog to empty his bladder; he no longer had the balance to lift his leg. He peed and peed and peed. Ally wondered if there might be something wrong with his kidneys. But this wasn’t her problem now, was it? She was finding it difficult, in her present circumstances, to decide how far her sense of obligation ought to stretch. She opened the drawer that contained this question, then immediately slammed it shut again, flinching from the prospect of delving too deeply, worried that if she tried to draw a line at one particular point, she might discover it was impossible to draw it anywhere. Maybe everything was her problem now.

Back in the kitchen, the doctor was still slumped in his chair. It made Ally feel sad, seeing him like this: so defeated. She wanted to cheer him up, to reassure him that things were going to be okay, even though this obviously wasn’t the case. Stan was the keystone; without him, the arch collapsed, and without the arch, the roof must fall. Ally could see no point in pretending otherwise.

“Can you handle her for a few days?” Dr. Thornton asked. “On your own?”

“Of course,” Ally said, trying to sound more upbeat about this prospect than she actually felt. She didn’t know what the doctor imagined might change in the coming days. Whether it was today or tomorrow or next week or the one after that, someone was going to come and take Eleanor away.

“I’ll stop by in the morning to check on things,” the doctor said. “And you can call me anytime.”

Ally thanked him. There was an awkward moment at the door, when it seemed like he thought she might expect a consoling hug. Maybe she did, too—she felt herself leaning toward him and only managed to regain her center of gravity an instant before the point of no return. The doctor touched her shoulder, gave her something between a pat and a squeeze. Then he was gone.

If Ally had been at any risk of imagining she might be able to fill the vacancy Stan had left behind—that she might find a way to keep watch in the house until death came to claim Eleanor in her turn—the remainder of that first day alone there would’ve cured her of all such illusions. Ally couldn’t understand how Stan had managed on his own for so many years. Eleanor had a habit of wandering. She was always shifting from one room to the other, searching for something, though if you asked her what it was, she was never able to remember. Sometimes she’d drift outside: she’d head to the aviary and try to drag open the barn’s door, or start to shuffle down the drive toward the road, or just stand on the lawn, staring at the steep hill beyond the barn with an air of concentrated attention—a deep sort of listening—that Ally always found slightly spooky. With Stan around, it had seemed easy enough to keep track of her. But now, as soon as Ally glanced away, Eleanor would vanish. For some reason, she kept taking Bo out and tying him by a length of rope to the hitching post at the far edge of the lawn. Ally would have to go out and free the poor dog, and while she was doing this, Eleanor would turn on the stove, or take off her clothes again, or remove all the food from the refrigerator and stack it neatly on the kitchen floor.

“Where’s Ed?” she kept asking. “Have you seen Ed?”

It didn’t matter how Ally answered; whatever she said was immediately forgotten. So there seemed no point in struggling to communicate some version of the truth. Instead, Ally told Eleanor that Ed had gone to the store, that he was resting, or showering, or out for a long walk. And no matter where she said he was, the same questions would be asked a moment later.

“Where’s Ed? Have you seen Ed?”

It was a relief when the sun finally began to set. They had soup for dinner (Where’s Ed?), and then Ally helped Eleanor take a bath (Have you seen Ed?), and brush her teeth (Where’s Ed?), and pull on her nightgown (Have you seen Ed?), and climb into bed. It was then that things got tricky again. Every time Ally turned out the light and tried to leave the room, Eleanor would get up and follow her (Where’s Ed? Have you seen Ed?). Ally assumed the old woman would eventually grow tired of this dance—that if Ally could just persuade her to lie motionless in the darkness for a handful of minutes, sleep would come and lay hold of the old woman. But it wasn’t working that way: it was Ally who was growing tired. Finally, in desperation, when Eleanor yet again asked if she’d seen Ed, Ally answered: “I’m Ed.”

“You’re not Ed.”

“Of course I am. Why shouldn’t I be Ed?” This little experiment might have ended here, had Ally not detected the slightest flicker of uncertainty in Eleanor’s expression. Ally seized on it, stepping to the big bureau against the wall. She dragged open the top drawer, then the drawer beneath it, searching till she found a clean pair of Stan’s pajamas. She took off her shorts and T-shirt and pulled on the pajamas while Eleanor watched from across the room. “Come on, love,” Ally said, imitating Stan’s voice as closely as she could. “Time for bed.”

Absurdly, it worked. When Ally climbed beneath the sheets, Eleanor did, too. Ally reached to turn out the light, and, as she settled back onto the pillow, Eleanor shifted toward her, resting her head heavily on Ally’s shoulder. Ally’s plan was to wait for Eleanor to drift into sleep and then quietly slip out of the room. But each time she attempted this—with Eleanor softly snoring only inches from her face—Eleanor would startle back awake, clinging to Ally’s arm with surprising strength. “Ed?” she’d cry out.

“Yes?” Ally would say.

“Where are you going?”

“Nowhere, love. Go back to sleep.”

At some point, Bo entered the room. He stood beside the bed, sniffing loudly. Then he turned and shuffled back out. It was hot, especially with Eleanor’s plump body pressed so tightly against her side, and Ally was beginning to sweat through Stan’s pajamas. She’d never be able to sleep here—she was certain of this. For one thing, it was impossible not to remember that this was where the old man had died, in this very bed. Ally thought she could still detect the smell of shit in the room. Or was it the stench of death itself?

Bo returned. He stood in the darkness beside the bed. Ally reached out a hand to pat him, aiming for the sound of his sniffing, but all she touched was air. It gave her a shivery feeling, as if the dog weren’t actually there. To calm herself, she thought about leaving, planning her escape as if it were something she might actually attempt. She could get up in the morning, feed Eleanor, install her on her chair in the aviary, then climb into the Volvo and go. She knew where Stan had kept the ATM card; she even knew the code—sometimes she’d made withdrawals for the Hobbits as she ran her errands down in town. The car, whatever cash she could get from the bank: that was all she’d need in order to vanish. By nightfall, she could be in Philadelphia, or Buffalo, or Wilmington, cities she’d never visited before, blank slates, new starts. Ally lay on her back in the hot room, wondering if there were people who would do such a thing—no, that’s not true, because of course there were such people: what she wondered was if she herself could ever be that type of person. She was thinking about the Titanic, the listing deck, the band playing, the icy sea. There were men who’d donned dresses, she knew, pretending to be women so that they could claim a spot for themselves in the meager allotment of lifeboats. Ally didn’t want to be like that, but she didn’t want to be left on the deck, either; she didn’t want to stand there in the North Atlantic night, while the ship sank beneath her feet . . . and Mrs. Henderson was making her retie the knots, raising her voice above the wind, telling her to go over and around and then under again, and Ally (always so clumsy with her hands, but all the more so now, her fingers cramping in the cold rain) kept losing hold of the rope. Part of her realized she was dreaming, and it was this part that roused her back into waking, into the Hobbits’ stuffy bedroom, with its faint smell of shit. It was still dark, but later now, and empty—the bed, the room.

Ally pushed herself into a sitting position. She listened. Softly, in the distance, she could hear someone whimpering. It was faint enough for Ally to think that she might be imagining it—but no, there it was again, louder now, irrefutable. She climbed out of bed, stood in the dark room, trying to find her bearings, to shake off the last vestiges of sleep; she wanted to be certain she wasn’t dreaming. The pajamas clung to her body, heavy with perspiration, smelling of both her and Stan all at once.

“Eleanor?” she called.

The whimpering continued. It wasn’t Eleanor, Ally realized: it was Bo. She started out of the room, moved quickly down the hall into the kitchen. The dog was outside, Ally could tell. His whimpering had roused the birds; they’d begun to caw and shriek and whistle in the shuttered barn. Ally was hurrying—across the kitchen, into the mudroom—she didn’t pause to turn on a light, so it was a shock to come across Eleanor, standing there in the darkness, naked again, staring out the screen door toward the lawn.

“Eleanor?”

Eleanor held up a hand: “Shh.”

Outside, Bo’s whimpering climbed a notch, becoming a sustained sort of yelp. There was pain in the sound, and fear, and helplessness. Ally pushed past Eleanor, out the door. The old woman grabbed at her arm—again with that surprising strength of hers—but Ally wrenched herself free. The dew on the grass felt cold against her bare feet, almost like frost. It was a pleasant sensation, sobering and clarifying: now, at last, she was fully awake. There was a half-moon, hanging just above the barn, but a cloud was moving slowly across its face, which meant the yard was dark enough for Ally to need half a dozen steps to realize that there wasn’t, as she first thought, a child lying in a white dress halfway across the lawn: it was Eleanor’s nightgown, cast aside on the grass. Bo would be tied to the hitching post, Ally knew, and as she approached, she began to hear not only his continued keening, but also a wet slapping, a heavy panting, and what sounded like the flapping of a flag in a light breeze. She could see him then, struggling to rise, falling, struggling up again—this was the slapping sound, his paws churning at the muddy puddle he’d peed into the dirt around the hitching post—he fell, he whimpered, he fell again. “It’s okay,” Ally said. “I’m here. It’s okay, sweetie.” She was reaching to untie the rope from his collar when the moon broke free from its masking cloud, and she saw the thing hanging from his neck. She flinched back with a stifled scream.

Her first, startled impression was that it was some sort of immense insect, oval shaped, at least a foot long and half again as wide, with something frighteningly spider-like about it, the sense of multiple legs emerging from its central torso. Then Bo fell again, and a pair of wings spread open from the creature’s back; they gave a single flap to stabilize the beast. The wings were shockingly long, with a leathery appearance; Ally could make out the bones beneath the skin, even in the moonlight. There was fur, too: on the creature’s back and legs—brown or black, Ally couldn’t tell which. And the legs (there were six of them, she saw, with a tug of nausea) were prehensile; each of them ended in a monkey-like hand, all six of which were gripping tightly at Bo’s fur. Its head was the size of a grapefruit, its face buried in the dog’s neck: burrowing, feeding.

Bo made no effort to rise again. He seemed to sense Ally’s presence, and it was as if her arrival had prompted him to relinquish his fight: she would either free him from his tormentor, or he’d succumb.

The birds continued to cry out in the barn. The parrot was calling: “Ed . . . ! Ed . . . ! Ed . . . !” Another cloud obscured the moon, and Ally felt her panic ratchet upward—the creature was just a shadow now, a deeper darkness against Bo’s black body, its wings going flap, flap. Ally backed away. One step. Then another. Stan had been digging a hole the day before—a rhododendron beneath the kitchen window had died, poisoned, Ally suspected, by Bo’s urine, and Stan had been working all afternoon to excavate its withered remains. He’d left the job half-finished, intending to resume his digging in the morning: the shovel was still leaning against the side of the house. Ally turned, started for it at a run.

Behind her, Bo let out a long, warbling cry of pain.

The shovel was exactly where she’d pictured it, waiting for her. She headed back across the lawn, grasping the tool’s handle in both hands, like a baseball bat. The moon emerged again, just as she arrived at the hitching post. Bo had rolled onto his side; she could see his chest rising and falling, could hear him panting. The creature had folded its wings back into its body. Ally watched it open one of its furry hands, then reach and claim a better grip.

She swung with all her strength.

Her fear of the creature, her revulsion, seemed to give her strength. The shovel’s blade landed with a loud thump. Bo yelped, kicked his legs. The creature relinquished its hold on the dog. It fell to the ground, instantly righting itself, and turned to face its attacker. Ally had time to register the thing’s face: round and pale and hairless, with a pair of large eyes and what she at first mistook for a flat, simian nose. But then this orifice opened, revealing a set of startling white teeth—sharp and double-tiered—and she realized the thing had two mouths, this smaller one where a nose would normally reside, a few inches above its much larger companion. Both were stretched wide now. Ally could see rows of teeth, a pair of thick pink tongues. The creature shrieked, enraged. Then it spread its wings and leapt into the air, flying straight at her.

Ally swung again. This time, it was nothing but reflex, straight from the spine, her animal core taking command; she managed a glancing blow that knocked the creature back onto the ground. It was in the air again so quickly that it seemed as if it had bounced off the dirt, like a ball. It was still shrieking. Ally swung, connected; the thing thudded against the earth, sprang into the air once more, and this time when Ally swung, she heard the crack of a bone snapping.

The creature fell to the lawn, scrambling with its legs in the dirt, one wing wildly flapping, the other dragging, its shrieking taking on a higher note, pain mixing into its fury: Ally lunged forward and swung again—and again—and again. She could hear more bones cracking, could feel them break through the shovel’s wooden handle, and the sensation seemed to drive her onward, into a growing frenzy. She would’ve killed the thing, would’ve continued swinging until her strength gave out, pounding the creature into the sodden earth, but then, in the brief hesitation between blows, she glimpsed its face. There was something unavoidably human in those eyes—intelligence, terror, bewilderment—and it knocked Ally back into herself. She heard the creature’s cries: the rage had vanished. Pain was triumphant now, with a childlike undertone suddenly emerging; the creature sounded like a frightened toddler. It was trying to crawl away. All of its limbs but one appeared to be broken, and it kept grabbing at the dirt with its single undamaged hand, struggling to pull the limp weight of its body out of the yard, into the trees, to what it must’ve imagined was safety—struggling, failing.

Ally heard herself start to sob. She dropped the shovel, stepped toward Bo. The dog was still lying on his side, eyes shut, panting. Ally untied the rope from his collar. “Come on, sweetie,” she said, crying, wiping at her face, at the tears, the snot. “Can you get up?”

Bo lifted his head, peered blindly toward her. His tail thumped against the ground, a feeble wag . . . wag . . . wag. Ally didn’t think he’d be able to rise, but she prodded at him anyway; she wanted to get him back into the house, away from his attacker. Bo groaned, rolled onto his stomach. She pulled at his collar, straining to lift him, and he surprised her by lurching upward; he swayed, almost fell, but then, when Ally gave another tug, started to stumble back across the lawn toward the house, whimpering with every step. Ally glanced back at the creature as they fled. It had fallen silent now—so had the birds; the only sounds were Ally’s weeping and Bo’s cries of pain as he staggered forward. Ally could see the creature continuing to move, that single limb reaching to claw impotently at the dirt.

Eleanor was still standing in the mudroom, just inside the screen door. She followed Ally and Bo into the kitchen, watching as Ally led the dog to his bed beside the stove. Bo collapsed onto the bed, immediately shut his eyes. Ally nudged his water bowl toward him, but he ignored it. There was blood on his fur, thickly caked—his neck, his shoulder, most of his flank—but when Ally tried to examine his wound, the dog gave a yelp and started to thrash his legs, scrambling backward. So Ally let him be. It took him a minute to stop whimpering; it took Ally even longer to stop crying.

“Oh, Ed,” Eleanor said. “No, no, no. Oh, dear. Oh, no.” She was standing in the doorway, still naked, wringing her hands, staring at the dog in obvious distress.

“It’s okay,” Ally said. “He’ll be okay. Here—sit.” She took Eleanor by her elbow, guided her to a chair at the head of the table. Once she got her seated, Ally turned and went out through the mudroom again. She peered at the lawn through the screen door. Dawn was just beginning to break; the first traces of red had appeared in the east, beyond the barn. There was already enough light so that, even from this distance, Ally could discern the creature, feebly shifting about in the dirt beside the hitching post.

She heard a noise behind her, in the kitchen, and when she turned, she saw that Eleanor had gotten up from her chair. She was standing over Bo, dragging at his collar, trying to pull him to his feet. Ally hurried toward them: “Leave him. He needs to rest.”

“We have to,” Eleanor said.

“Shh.”

“The sun’s coming up.”

“I know. Stop it now. Let him go.” Ally eased Eleanor’s grip off Bo’s collar, led the old woman back across the kitchen.

Eleanor was peering toward the window, the sky growing lighter with each passing second. She covered her mouth with her hand. “What do we do, Ed? What do we do?”

Ally sat the old woman down in the chair again.

Then she did the only thing she could think of: she picked up the phone and called Dr. Thornton.

She’d awakened him, she could tell. There was a burred quality to his voice, a sleepy lag before he recognized her name. But she’d hardly begun to tell her story when she felt him snap into clarity. The whimpering . . . Eleanor standing in the mudroom . . . Bo tied to the hitching post . . . the creature hanging from the dog’s neck . . . the shovel—that was as far as the doctor allowed her to get. “Stay inside,” he said. “I’ll be right there.” And then he hung up.

Ally got Eleanor into her robe. She placed a bowl of Cheerios on the table in front of her, a glass of orange juice. Then she quickly changed out of Stan’s pajamas, back into the shorts and T-shirt she’d been wearing the night before. There was blood on the pajamas: spattered and smeared. Whether it was Bo’s or the creature’s, Ally couldn’t tell. By the time she returned to the kitchen, the dog was asleep. Ally worried for an instant that he might’ve died, but then she heard that familiar rising sequence of inhalations and the long wheezy sigh that followed. Eleanor was eating her cereal. She’d grown quieter as soon as the sun broke free of the trees, filling the room with light: it was possible, Ally supposed, that she’d already forgotten the entire drama. Ally stepped into the mudroom, peered out the screen door. The creature was still there, lying in the dirt beside the hitching post. It had stopped moving now.

Ally went back into the kitchen, poured herself a glass of juice, quickly drank it. Then she got Eleanor onto her feet, led her through the mudroom, out onto the lawn. She knew the only way to keep Eleanor occupied was to put her in the barn with the birds. All the way across the yard, she worked to keep herself from turning to glance at the hitching post. Even in the daylight, even with the creature so grievously wounded, it felt frightening to be out in the open again. She pulled back the big wooden door, set up Eleanor’s chair. Eleanor was still in her bathrobe—teeth unbrushed, body unbathed, hair uncombed—but she didn’t seem to mind. She sat down, smiling toward the gray parrot, who was perched above her, on the edge of the hayloft. “It’s raining,” the bird said, muttering the words. He lifted his right foot and gnawed at it for a moment with his beak. Then he spoke again, with more vehemence: “It’s pouring!” All of the birds were calmer now. It was almost as if nothing had happened in the night.

Ally could hear Dr. Thornton’s car approaching down the drive. She stepped to the doorway and watched through the netting as the doctor parked, turned off the engine, climbed out. She assumed he’d come to the barn when he saw her standing there, but he just glanced in her direction and then walked to the hitching post instead. He stood for a long moment, staring down at the creature. Ally pushed aside the netting and started toward him.

Dr. Thornton didn’t hear her coming, but the creature seemed to. It had gone still once the sun had risen—quiet, too—but now it roused itself with a screech of panic, making the doctor jump. The creature’s hairy little leg started to thrash about, its head twisting to peer at Ally, its eyes looking huge in its tiny face, terrified. The doctor turned, following its gaze. He had an uncharacteristically disheveled look to him: it was a window into the urgency of his morning thus far—roused from sleep by her call, hurriedly dressing, skipping the shower, the razor, grabbing whatever clothes came to hand, pulling on his shoes, plucking up the car keys, rushing out the door. It seemed improper somehow for Ally to glimpse him in such a state, and she realized for the first time how much care he normally took with his appearance. He was a vain man—how could she have missed this?

The creature kept looking at her. Screaming. Thrashing.

“Do you know what it is?” Ally asked.

The doctor nodded.

“You’ve seen it before?”

He shook his head. “But I know what it is.”

Ally hugged herself. She wished the thing would fall silent again, but if anything it only seemed to be growing louder. She glanced around them, at the trees bordering the yard, the hillside above the barn. “Are there others?”

The doctor didn’t answer. He said: “I think it might be best if you went back inside.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I have to make some calls.”

“To who?”

“Please, Ally. Go back into the house.”

So she went inside. She showered, put on fresh clothes, combed out her hair. She stood at the kitchen sink and ate a piece of toast, watching out the window as the doctor paced in the dirt beside the hitching post, on his cell phone, making his calls. As soon as Ally had left, the creature had fallen silent again. Eleanor remained in the barn with the birds. Every now and then, Ally heard the parrot call out: “Ed! Big Ed!” But otherwise, all was quiet.

The first car arrived thirty minutes later. Ron Hillman, the village pharmacist, was driving. He climbed out and stood with the doctor, both of them frowning down at the creature, their hands on their hips. Ally watched them as they talked. Whatever Ron was saying, the doctor didn’t appear to like it; he kept shaking his head. It was odd to see Ron without his white coat, dressed in khaki shorts and a golf shirt, his legs looking so pale and thin in the early morning sun. Another car arrived: this one held Philip and Christina Larchmont. They joined Ron and the doctor by the hitching post, forming a little circle around the wounded creature. Philip was the village’s mayor. He owned a small trucking company. In the winter, according to what Stan had once told Ally, he liked to head out in one of his trucks and help plow the local roads, charging nothing for this service. Christina worked part-time in the little library beside the village green. Ben Trevor, from the hardware store, was the next to arrive, then Mike and Jessica Stahl, then Mickey Wheelock. Ally thought she should make a pitcher of iced tea, bring it out to them on a platter, but there was something about the way everyone kept turning to glance toward the house that gave her pause. She couldn’t say precisely how it made her feel, but it wasn’t a pleasant sensation—wary, a bit uneasy. The doctor had told her to wait inside, so that was what she would do. She turned from the window, sat at the kitchen table, and tried not to think about the people on the lawn, tried not to think about the blood on Stan’s pajamas, tried most of all not to think about the creature.

Ally heard the sound of water softly falling, and when she looked up, she saw urine soaking the dog’s bed, running off it onto the floor in little rivulets: Bo had lost his bladder in his sleep. Ally tried to rouse him, but he just opened a single eye, stared blindly toward her, and then slipped back into unconsciousness. She was cleaning the mess up as best as she could, when there was a knocking at the screen door.

“Come in!” she called.

It was Christina and Jessica. Neither of them could’ve been more than a handful of years older than Ally, but there was something about both women—so stout and competent and matronly—that always made Ally feel very young. Whenever she encountered one or the other of them, she ended up wondering how she could’ve managed to live so many years without ever really growing up. The two women bustled into the kitchen with a friendly air of command, each talking over the other.

“Oh, dear,” Christina said. “Did someone have an accident?”

“We’ll take care of that,” Jessica said. She was already by the sink, rummaging in the cabinet underneath, pulling out a bucket, filling it with hot water from the faucet.

Christina stepped to the little closet beside the refrigerator, opened its door, found a mop. “Why don’t you try to get some rest?”

“Yes,” Jessica agreed. “It sounds like you’ve had quite the night, haven’t you?”

“Would you mind if we made some coffee for the men?”

“What’s happening?” Ally asked.

Christina waved the question aside. “It’s all right, honey.”

Jessica nodded, hefting the bucket out of the sink. “Everything’s going to be fine.”

Christina came toward her, mop in hand. She took Ally by her elbow, guided her toward the doorway. “You go on upstairs. Try to lie down.”

Ally allowed herself to be herded in this fashion; she was too worn out to resist. But she didn’t believe she’d ever be able to sleep. She climbed the stairs to her room and stood at the window, watching the men in the yard. Ollie Seymour, the village barber, had arrived. And Chad Sample, who owned the house just up the road. Ally couldn’t see the creature from this angle, just the men gathered around it, talking among themselves, turning now and then to glance at the house. She lay down on the bed. She didn’t expect to sleep, or even to rest, but her head had begun to ache, and she thought it might help to shut her eyes. There was the Hobbits’ Volvo, and the bank card . . . she could still just vanish . . . but all those cars were blocking the drive now . . . and the doctor had told her to stay in the house . . . and the women in the kitchen had sent her upstairs . . . she should remind them to bring Eleanor her lunch . . . there was roast beef in the fridge . . . Eleanor always enjoyed roast beef . . . they could fetch a jar of pickles from the root cellar—

“Ally?” It was Dr. Thornton’s voice.

Ally glanced blearily around the room. She could tell from the way the light had shifted that it was much later now. She fumbled for the clock on the night table: it said 4:03. Somehow, she’d managed to sleep for almost six hours.

“Ally . . . ?” He was calling to her from downstairs.

“Coming!” Ally pushed herself off the bed, stepped out into the hallway.

The doctor was on the landing halfway down, peering up at her. “Would you mind joining me for a drive?” he asked. “There’s something I’d like to show you.”

Most of the cars had left. But Christina was still there, sitting in the kitchen with Eleanor. They were drinking tea and eating cookies. The kitchen had been cleaned; everything smelled sharply of bleach. Bo had been cleaned, too—his fur, his wound. He seemed to sense Ally’s arrival downstairs. He lifted his head, gave a single slow wag to his tail. Ally had washed her face, changed her T-shirt. She asked Christina if she’d be okay here on her own, and Christina smiled, waved her toward the door.

The doctor was waiting in his car, its engine already running. When he saw Ally approaching, he climbed out, stepped around to the passenger side, and opened her door for her. It made Ally feel like this was a date, and—ridiculously—she felt herself begin to blush.

There was no sign of the creature. As they were pulling away from the house, Ally asked: “Did it die?”

The doctor shook his head.

“Where is it?”

Dr. Thornton made a vague gesture. “Ron Hillman took it into town.”

Ally assumed that this must be where they were headed, too, but then the doctor turned north at the first crossroads they reached, and they began to climb higher into the hills. They passed the house where Ally had seen the goose, and then the doctor made another turn, onto a narrow gravel lane, and suddenly they were in a part of the country Ally had never glimpsed before. Pine trees grew close to the road on both sides, cutting off the view.

“You’ve seen the war memorial, I assume,” the doctor said. “On the green?”

Ally nodded.

“Did you ever look closely at the names?”

There was a carved scroll at the base of the memorial, Ally knew; it listed the young men from the village who’d died fighting to keep the union whole. But she’d always been too unsettled by the statue’s ghostly grimace to pause long enough to read the names. She shook her head.

“Seventeen names,” the doctor said. “And two are Thorntons: Thaddeus and Michael. Which is all just to say that my family has lived in the village for a very long time. One of the first white men to establish a farm in this part of the state was a Thornton. And for all those many years, we’ve been living with the skad.”

“The skad?”

The doctor nodded. “The Abenaki Indians used a longer word, which sounded something like ‘skadegamutch.’ When the first white settlers came, they shortened this to skad. If you go to Harvard’s Houghton Library, they have a book with a drawing a French priest made in 1742. Mythical Beasts of the New World. It shows the creature that you encountered last night. Quite a fine rendering, really. Only much larger.”

“Larger?”

Another nod from the doctor. “If you think of a bear? What you saw was a cub. A young cub. Recently weaned, would be my guess.”

Ally shut her eyes. She imagined a creature like the one she’d fought, imagined it the size of a bear. Then she pictured more than one of them, an entire clan or pack or troop, lurking somewhere in these hills.

“The Abenaki were hunters. And at some point, they developed a tradition. When they wounded an animal—a deer, a moose, a beaver—they’d leave it outside their encampments at night, tied to a tree, as an offering for the skad. In this manner, the two groups found a way to live in peace with each other.”

Ally thought of the animals she’d glimpse on her late afternoon runs. The old cow, the spavined donkey. “The hitching posts,” she said.

Dr. Thornton nodded. “The white settlers adopted the practice when they began to establish themselves in the area. Horses, cattle . . . as they neared the end of their usefulness, they’d be tied to a hitching post. Left out in the night.”

“And dogs.”

“That’s right—dogs, too.”

The gravel road came to an end. A chain had been strung across its path, from one tree to another. Beyond the chain, a narrow trail wound up the hillside, climbing steeply. It led to a house, which was just visible through the pines. Dr. Thornton put the car in park, shut off the engine. He didn’t undo his seat belt, didn’t reach to push open his door, and Ally was happy for this. There was something about the house she didn’t like.

“There were probably other times when the arrangement broke down,” the doctor said. “But the only occasion I know of for certain happened in 1973. A man named Bert Rogers was elected mayor of the village. Bert had served in the marines, a career officer. He’d been a lieutenant in Korea. He’d commanded an entire battalion in Vietnam. He was a serious man. A hard man. He decided it was time to resolve the issue of the skad—that there was something cowardly about how we’d been accommodating their presence in our lives. They were nocturnal creatures, and Bert argued that it ought to be possible for us to hunt them during the day. That the men of the village could hike up into the hills and ferret the creatures out of their caves and burrows. That they could kill the skad off.”

The doctor unhooked his seat belt, reached to push open his door. No, Ally thought. Whatever this is, I don’t want to see it. But when the doctor climbed out of the car, she found she couldn’t help herself. She climbed out, too. Then they started up the path through the trees, Dr. Thornton walking in front with Ally a few feet behind him.

“There were two problems with Bert’s idea, as it turned out,” the doctor said. “One is that it’s not as easy as it might seem to kill a skad. The juvenile you encountered last night—you broke both of its wings and most of its legs. But you didn’t kill it. And—given sufficient time—it will recover completely. Pretty much the only way to kill them, in fact, is to burn them. And even that isn’t as simple as it sounds—you have to burn them completely. You have to reduce them practically to ash.”

It was a large house, two stories, with a high, steeply slanting roof. And it was in ruins. It looked as if it had once been painted blue, but this was decades ago, and the weather had long ago stripped most of the color from the exterior. The windows were empty of glass; most of the shingles had blown free from the roof. Ally didn’t want to get any closer, but Dr. Thornton kept walking. So she did, too.

“The other problem,” the doctor continued, “is that while the skad are indeed more or less helpless during the day, at night, it’s we who are the helpless ones. So Bert Rogers and his men went up into the hills and attacked the skad while the sun was in the sky. Then, once the sun had set, the skad came down out of the hills and did their own hunting. And it turned out that they were far better at this than we were.”

The house’s porch had collapsed. To reach the front door, which was hanging partway open, the doctor had to prop a fallen shutter against the foundation and scramble up it, using it as a ramp. Then he turned and held out his hand to Ally. One part of her mind tried to tell her head to shake—no—but a more powerful part submissively ordered her arm to rise. Dr. Thornton grasped her by the wrist, pulled her up. He pushed the house’s front door all the way open, and they stepped into the building.

“This is where the Baggers lived,” he said. “Steve and Katherine and their four children.”

They were in a small foyer. Across from them, a flight of stairs climbed toward the second story. There was a long hallway to the left of the stairs, leading to the rear of the house. To the right, an archway opened into what Ally guessed had once been the Baggers’ living room. The doctor had retained his hold on her wrist. When he stepped toward the archway, he gave her a tug, pulling her with him. The room still showed evidence of its former occupants. There were the ragged remains of a brown carpet on the floor, a sagging couch, two armchairs, a large coffee table lying on its side, several broken lamps—even a painting lying faceup on the floor. It didn’t look abandoned, though. It looked vandalized, as if someone had come here one day long ago and worked to destroy the room, laboring at the task with a malevolent vigor.

Or no, Ally realized; that wasn’t right. It wasn’t one day. It was one night.

“After this—and two other similar incidents—the village turned against Bert. They went back to the old ways. They made peace with the skad.”

“How?” Ally asked.

“Careful,” the doctor said. She’d taken a hesitant step into the room, wanting, despite herself, to see what the painting depicted, and in the process her foot had come into contact with something lying among the tumbled debris littering the floor. The doctor pulled her back from it. Ally stared down at the object, struggling to decipher what it might be. It took her a moment, but then it came all at once: it was a hand, a child’s hand, stripped of flesh, only the bones remaining, the bones and the leathery brown ligaments that held them in place. Seeing this—really seeing it—yanked other objects in the room into focus. Beyond the couch: a dirty-looking pair of jeans, with a shattered femur poking through a tear in the denim. And then, between the two armchairs: what Ally had at first mistaken for a stone, revealed now for what it actually was—the top half of a man’s skull.

Inside, Ally could feel herself fleeing from this place. Fleeing and screaming. But she didn’t make a move, didn’t make a sound. She was conscious of the doctor’s grip on her wrist, conscious of the slant of sunlight through the glassless windows across the room. It was getting late, but how late? How soon would it be dark?

“Why is it still like this?” she asked.

“Like what?”

She waved at the room, the broken furniture, the tumbled bones. “All these years. Why hasn’t it been cleaned up?”

“It’s a gesture of respect.”

Respect? The word felt obscene to Ally; she couldn’t imagine it ever having any connection to such a setting. “Toward who?”

The doctor shrugged, as if he believed the answer ought to be obvious. “The skad.”

Ally felt exhausted suddenly: nauseated, and empty of any desire but the urgent need to leave. “I want to go,” she said.

The doctor nodded. “Of course.”

He seemed to think that by “go,” she meant leave the house. And, as a start, this would suffice for Ally. Dr. Thornton guided her back through the foyer to the front door; he helped her down to the ground, then began to lead her back along the winding path to the road. The dirt here was thickly carpeted with pine needles; their footsteps didn’t make a sound.

Go, go, go, go, go . . .

They climbed into the car, pulled on their seat belts. The road was too narrow for the doctor to turn around at first, so he had to drive in reverse, twisting sideways in his seat to see the way. Ally sat facing forward, watching the house slowly disappear into the trees.

Go, go, go, go, go . . .

They didn’t speak. The road finally widened enough for the car to turn around, and then the doctor drove more quickly. Ally felt herself begin to breathe again. She must’ve been breathing all along, of course, but for a while there it had felt as if she hadn’t.

Go, go, go, go, go . . .