LIST PRICE $17.99

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

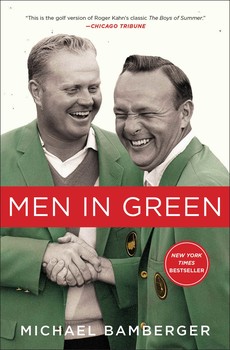

With “exceptional insight into some of America’s greatest players over the last half-century” (The Philadelphia Inquirer), Men in Green is to golf what Roger Kahn’s The Boys of Summer was to baseball: a big-hearted account of the sport’s greats, from the household names to the private legends, those behind-the-curtain giants who never made the headlines.

Michael Bamberger, who has covered the game for twenty years at Sports Illustrated, shows us the big names as we’ve never seen them before: Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Tom Watson, Curtis Strange, Fred Couples—and the late Ken Venturi. But he also chronicles the legendary figures known only to insiders, who nevertheless have left an indelible mark on the sport. There’s a club pro, a teaching pro, an old black Southern caddie. There’s a tournament director in his seventies, a TV director in his eighties, and a USGA executive in his nineties. All these figures, from the marquee names to the unknowns, have changed the game. What they all share is a game that courses through their collective veins like a drug.

Was golf better back in the day? Men in Green weaves a history of the modern game that is personal, touching, inviting, and new. This meditation on aging and a celebration of the game is “a nostalgic visit and reminiscence with those who fashioned golf history…and should be cherished” (Golf Digest).

Excerpt

Augusta beckoned, as she does.

I was heading there by way of Charlotte, made one wrong turn, and found myself on Wilkinson Boulevard, pointing for downtown. One wrong turn and my mind went into a drift. All these old-timey motels hanging on. Which one was it?

I was remembering a day from thirty years earlier. More than thirty. It was the night of my brother’s college graduation, and I was flying from Boston to Charlotte to caddie in a tournament there, a professional tournament, with stars in the field and a big cardboard check for the winner. Fred Graham, one of Cronkite’s lieutenants on CBS News, was on my flight, sitting in first class, smoking a cigar. It was Fred Graham, for sure. He had that scar on his chin.

Scars were more common then. When I was growing up—in the village of Patchogue on the South Shore of Long Island in the sixties and seventies—there were still World War I vets on the benches by the VFW Hall with scars both visible and hidden. (We all knew the phrase combat fatigue.) My baseball hero, Cleon Jones, had a scar on his right cheek, the residue of a young-buck car accident that had sent him flying through a windshield. I learned about this face-changing mishap in Cleon, his 1970 autobiography, which I devoured when it became available at the Patchogue Library. Soon after, in that same library, I found Cleon Jones’s phone number in Mobile, Alabama. What a thrill, to look at that exotic 205 area code and imagine the scene on the other end. And in that same vein, here was Fred Graham of CBS News with his positive-ID chin scar. I caught my breath. He was famous, yes, but it was more than that. He was a member of a nomadic tribe—newsmen—a group forever on the prowl, always going to some new place. It was May 1979. I was newly nineteen and looking to join the circus myself. Not Fred’s. It was Golf Road that was calling.

Wilkinson Boulevard, when I stumbled on it en route to Augusta all those years later, was just another misstep in a long series of them for me, on the wrong street, likely heading the wrong direction, temperamentally incapable of using a smartphone map. No matter. Little waves of happiness were washing over me.

The accidental tourist: I know the concept well. Here I was, in the throes of middle age, and the song of the road was playing at full volume again. It plays for all of us, doesn’t it? My own wanderlust is tempered by a powerful desire to get home, be home, stay home. Those urges were especially strong in the years when our kids were in the house. But they had grown into collegians. (My wife, Christine, once brought home a small sign: CHECKOUT TIME IS 18.) And even in our Swim Meet years, the pull of the road was always more than background music. In my line of work—sportswriter—if you’re home too long, something’s wrong.

I’ve never had a true office job, and in our married life Christine and I have both always been coming and going. Our honeymoon was seven months in Europe during which I worked as a caddie on Europe’s professional golf tour. On long drives, Christine read aloud Richard Halliburton’s The Royal Road to Romance. My parents had the massive Arthur Schlesinger biography of RFK that included a photo of Bobby in front of the King David Hotel—Jerusalem, 1948—when he was twenty-two with a gig as a reporter on the Boston Post. A snap that inspires me to this day.

My mother and father left Nazi Germany as children with their parents, and many years later they gave long formal interviews about their wartime experiences. They dressed up for the occasion, which my mother does with ease and my father less so. (His dress shoes all have Vibram soles.) My mother spoke of family vacations in a village near a Czechoslovakian forest in the 1930s and her fascination with the Gypsies on the edge of it, with their dark skin and light feet.

In 1959, when Khrushchev was coming to the United States, Mike Wallace was on TV conducting a contest: What one place should U.S. officials take the Soviet leader to show him the real America? The winner would get a car, and our family—with me on the way—needed one. In my father’s entry, he said the American hosts should have Khrushchev throw a dart at a U.S. wall map and wherever it stuck was where he would go, so that Nikita and his comrades back home would understand that democracy thrives everywhere in the United States. How did that not win?

One year my brother was given a globe with raised mountain ranges. That was a big deal. Our father had a collection of Mobil travel guides stacked on a basement shelf. I read them front to back. On our family trips, David would read those accordion Hess and Esso road maps for our father like he was reading the back of a baseball card.

David and I were devoted to the fine print of American life. We will know forever the name Lou Niss, traveling secretary of the New York Mets in the Cleon Jones years. He was in the team photo annually. What a job. Whatever that position actually entailed, I could not know. But he was at-large. In the agate type of the sports section in the New York Times, under the heading “Today’s Games,” whole cities were in transit: New York at St. Louis, Chicago at Philadelphia, Cincinnati at San Francisco.

All my youthful heroes were at-large: the ballplayers and the golfers, the beat writers and the war correspondents, the musicians and their silent roadies. A nod here to some hits from yesteryear: Peter, Paul and Mary singing “Five Hundred Miles,” Glen Campbell singing “Wichita Lineman,” David Wiffen singing “Driving Wheel.” If you told me any of those songs were conceived on the side of the road, it wouldn’t surprise me one bit.

Just came up on the midnight special

Honey, how about that

My car broke down in Texas

She stopped dead in her tracks.

Do you like how Wiffen’s car gets the feminine pronoun treatment, as ships and principalities once did? My senior-year roommate called his boat of a station wagon Betsy. Another roommate, a physics major, wanted to be a long-distance truck driver. A high school buddy who shined shoes at the village course where I played in Bellport, one town east of Patchogue, saved his tip money for flying lessons. We were all in transit, at least in our dreams. The touring-caddie thing persisted in me for years.

Golf is a road game. Professional golf, of course, but the game as it is played on Sunday mornings, too. You start in one place, head out, have various adventures along the way, turn around, come on home. Chaucer would have had a field day with it, and Updike did. In one of the most beautiful sentences I know, from a short story for the ages, Updike describes an American banker on a Scottish links: “This was happiness, on this wasteland between the tracks and the beach, and freedom, of a wild and windy sort.”

I am certain of little—I am leery of the overconfident reporter—and at nineteen I knew even less. But I knew what anybody with a TV might know: Every week a group of professional golfers assembled in some new and glamorous place and played a leisurely ball-and-stick game for money and glory. I was never going to be one of those golfers. Even with the advantage of starting young, in gym class at South Ocean Avenue Middle School, I never was much better than an 85 shooter at marshy Bellport, where I knew every hump. (In middle age, I have been besieged with the yips, a putting illness that takes away your desire to write down scores.) But I was aware that the golfers on our family TV all had caddies. That’s where I saw my opening and my pathway to the circus.

In the winter of ’79, in the long winter break of freshman year, I had a brief stint catching T-bars flung by dismounting night skiers at the top of the Bald Hill Ski Bowl. (Named, we always said, for its distinct lack of snow.) On a Saturday afternoon in late January I was watching the Andy Williams San Diego Open in my parents’ living room. If golf was on TV, I watched. (My parents and brother had no interest. I had golf for myself.) At one point, CBS decided to show a journeyman doing nothing more than playing well: Randy Erskine, a reliable voice told us, of Battle Creek, Michigan.

I located this Randy Erskine of Battle Creek as I located Cleon Jones of Mobile. I wrote to him and asked him for a summer job as his traveling caddie. If the phrase tour caddie existed then, I doubt I knew it. The letter led to a phone call, which led me to a flight to Charlotte, site of the Kemper Open, on a May evening in 1979, when Fred Graham was sitting up front.

I headed out of the Charlotte airport that night and walked over to Wilkinson Boulevard and found a motel room for maybe fifteen dollars. It had to be the first night I was alone in a rented room. Early the next morning, the lady owner gave me a bowl of Raisin Bran and a tiny glass of orange juice and I was off.

The hair on Randy Erskine’s arms was bleached blond by the sun and he kept his heavy watch, along with his wallet and wedding ring, in a purple velvet Crown Royal bag, which he stowed in his golf bag while he played. He had narrow hips that didn’t rotate much on his backswing and a big shoulder turn. He used a Ping Pal putter, the same model used by my putting hero, Tom Watson. (Watson, so bold on the greens, made everything.) I had brought a tiny tool to clean the grooves on his irons, and that seemed to impress Randy. He played a practice round with a golfer named John Adams.

After one practice round, I found myself sitting in the back of a camper-van set up for the week in the parking lot of the Quail Hollow Country Club. Three touring pros—Randy, Doug Tewell, and Wayne Levi—were the real occupants of that camper-van, but nobody was chasing me away. Wayne Levi’s denim golf bag was parked outside, standing up on its own. A rap session, tour-style, was under way. To this day, it all seems so unlikely. A fourth pro, a lanky man named Don Pooley, came by with his wife, and Randy said, “The Pooleys!” It was like a golf commune.

Randy Erskine’s golf skill was like nothing I had ever seen, not up close. But his two-day total—150 shots, each of them accounted for on scorecards and sworn to with his signature—left him outside the cutline. His presence would not be needed for the Saturday and Sunday rounds. He made nothing that week, not on the greens and not in the way of a paycheck. Still, he stayed around to prepare for the thirty-six-hole U.S. Open qualifier that would be played on Monday.

People were talking about how the United States Golf Association had essentially forced Arnold Palmer, who hadn’t met any of the automatic eligibility requirements for the ’79 Open, to play in that qualifier. In other words, the USGA, in its hard-boiled wisdom, had not given a special exemption to the game’s most popular and revered player, who was then chasing fifty. There were people who were offended by the way Palmer was being treated. But Palmer was registering no such complaint. He would not put himself above those who had to qualify.

Randy allowed me to use the second bed in his Holiday Inn room that weekend. (Amazing.) When we showed up early on Monday morning at the Charlotte Country Club, we found out that Randy would be playing right behind Arnold Palmer himself.

“Great,” Randy said. “We gotta play in his wake all day.”

I felt he was feigning frustration, and noted his use of we. Randy Erskine was a touring professional in the vicinity of Arnold Palmer. How could that be anything but good?

There were at least a hundred people following Palmer that day, but it was never anything like bedlam. Palmer’s hair was already silver and his skin was bronzed. Palmer made it—he played his way into the U.S. Open. Randy did not. Still, he paid me one hundred dollars for the day. (Half that would have been generous.) He wasn’t playing in that week’s tournament in Atlanta. The week after that was the U.S. Open at Inverness in Toledo, Ohio, and he had just failed to qualify. But he would be playing the following week, in the Canadian Open. He said I could work for him in Canada.

And here I was, thirty-something years later, back in Charlotte, heading to Augusta in the name of Sports Illustrated. I got myself from Wilkinson Boulevard to Billy Graham Parkway to I-77 and motored my way south. I could not identify my old motel. Maybe it was gone.

I found myself thinking, for the first time in forever, about that long-ago Monday morning at the Charlotte Country Club, Arnold Palmer arriving in a shiny white Cadillac from a dealership that bore his name. He emerged from his grand chariot. Everybody inhaled. Time stopped. Arnold Palmer, in the flesh.

• • •

In October 2012 the Ryder Cup was played at Medinah, outside Chicago, and my assignment for the magazine was to help Davis Love III write a deadline first-person piece about his experience as Ryder Cup captain, a task that would be fun if the Americans won and challenging if they did not. Late at night, after the first day of the three-day competition, I was in a downtown restaurant by myself at a table with a paper tablecloth, and I found myself writing names on it. The names came to me quickly. I marked one column LIVING LEGENDS, the other SECRET LEGENDS.

LIVING LEGENDS

Arnold Palmer

Jack Nicklaus

Gary Player

Ken Venturi

Tom Watson

Curtis Strange

Fred Couples

Ben Crenshaw

Hale Irwin

SECRET LEGENDS

Sandy Tatum

Jaime Diaz

Billy Harmon

Neil Oxman

Dolphus Hull (aka Golf Ball)

Randy Erskine

Cliff Danley

Chuck Will

Mike Donald

Maybe I was subconsciously filling out lineup cards for a National League game, I don’t know, but when I was done I had two columns with nine names each for a total of eighteen—golf’s holy number.

During dessert, I decided to add Mickey Wright to the Living Legends list. The Big Three of the modern American golf swing are Ben Hogan, Tiger Woods, and Mickey Wright, and the list just didn’t look right without her. (The first golf book I read was Power Golf by Ben Hogan, published originally in 1948. It was a hardcover, and I read it outside with a club in hand. Where my mother found it I have no idea.) When I added Mickey, I took off Gary Player, a nod to symmetry more than anything else. That move, unintentionally, made the list all-American. Seventeen American men and one American woman.

The Living Legends were all players. The Secret Legends list included a club pro, a teaching pro, a tour caddie. A tournament director in his sixties, a TV producer in his eighties, a former USGA president in his nineties. They had all shaped my life. They all, in different ways, had driven deep stakes into the game long before I started poking around in it in the mid-1970s. Because of that, they were all elder statesmen to me—even Fred Couples, less than six months older than I.

Later, I got out a map and put a little check mark by each legend’s hometown. Before long, I had red marks in Pennsylvania, Michigan, California, Texas, Virginia, Ohio, and some other states. I concocted a vague plan to try to see each of them, notebook in hand, wherever I might find them. I got a little shiver. Does anything give a man more of a sense of purpose than a list?

My combined list had built-in problems. I didn’t know if Golf Ball was alive or dead. Fred was impossible. (Likable but impossible.) Palmer could be a challenge to interview. Mickey Wright didn’t even come to the USGA museum for the dedication of its Mickey Wright Room. Nicklaus was far more interested in his work as a golf-course architect than in revisiting his old playing days.

Still, it was a good list. In that great episodic TV show of my youth—American Golf in the ’70s!—all eighteen had a role. Bit or starring or in between, they were all there.

My plan, to the extent that I had one, was to pack these questions in my Target knapsack, along with my Lipitor and my hearing-aid batteries and my notebooks. “What was it like? Who did you hang with? How does then look to you now?” Or ditch all that and steal a question from the Proust Questionnaire in Vanity Fair: “When and where were you happiest?” A difficult question to answer, at least honestly. I wondered if I could answer it myself.

• • •

I have heard Palmer, Nicklaus, and Watson all say the same thing, each in his own way: I wouldn’t trade places with Tiger Woods for all the money in the world. Gary Player, too. “Do I wish I had Tiger’s access to private jets?” Player once said to me. “Yes. Do I wish I could have played with his equipment? Yes. But would I trade any aspect of my career and life for his? No.”

I don’t believe that things were better, to use a phrase Woods started using when he was about twenty-six, back in the day. I don’t think that for a minute. I like flying in smoke-free planes and playing at clubs that would not have had me back in the day. But you are not going to convince me that Dustin Johnson is a more interesting person than Lee Trevino. You’re not going to convince me that The Big Break VI: Trump National on Golf Channel will have anything like the staying power of Gene Littler versus Byron Nelson at Pine Valley on Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf. You’re not going to convince me that any sport-centric website is going to cover the game with the depth that the New Yorker did when Herbert Warren Wind was writing just a few golf pieces a year for the shiny weekly.

Dip into various golf events from Herb’s era—Roberto De Vicenzo of Argentina losing the Masters in ’68, for example—and you’ll find that Herb covered it at length, in depth, and with humanity. Yes, you had to wait a few weeks, or longer, to get his story, but it was worth the wait. His work has held up. I read Herb’s story about Di Vicenzo signing an incorrect card twenty years after the fact. It’s some piece. As for the editors who signed off on its title, they knew what they were doing: “Rule 38, Paragraph 3.”

Or, if you like, 38:3. Golf’s rules come up in the game’s various write-ups, with citations that look like chapter-and-verse biblical references. Maybe your eyes are rolling. The fact is, the rules are the spine of the game, at least when it is played seriously. I am nothing like an expert, but I do have an abiding interest in how the rules govern play. Maybe this interest in laws and their application is in my DNA. My grandfather’s main hobbies were collecting stamps and studying Jewish law, and his brief, one-column obit in the New York Times ran with this headline:

DR. S. B. BAMBERGER,

CHEMIST, TALMUDIST

When I read The Great Gatsby for the first time, I noted with interest that Fitzgerald made Daisy’s friend Jordan Baker an elite golfer who once was accused of cheating: “At her first big golf tournament there was a row that nearly reached the newspapers—a suggestion that she had moved her ball from a bad lie in the semi-final round. The thing approached the proportions of a scandal—then died away. A caddy retracted his statement, and the only other witness admitted that he might have been mistaken.”

Whenever a rules dispute comes up, you might ask yourself: How would Roberto have handled it? De Vicenzo blamed nobody but himself at that ’68 Masters. He said, “What a stupid I am.” In word and deed, he was saying that a golfer is responsible for his scorecard. Any society with an underlying respect for rules is off to a running start, provided the rules make sense. It helps keep things civil.

Along those same lines, golf has a weird ability to foster camaraderie. Most of my enduring friendships have come through golf. The modern golf tour, if you can even use the word tour anymore, strikes me as lonely. (Must be all that money.) But I don’t think it was for Arnold and Gary and Jack. Gary Nicklaus, Jack and Barbara’s third son, is named for Gary Player, because the older Nicklaus boys had so much affection for “Uncle Gary.” I will never let go of that moment in May ’79 when Randy Erskine and his buddies were sitting in the back of that camper-van, fixing their backswings and plotting their futures.

It was no great shakes, 1979. A swamp rabbit attacked Jimmy Carter during a presidential fishing trip in Plains, Georgia. But it was a good year for golf. In that same state, in the same month, Fuzzy Zoeller won the Masters in a playoff over Ed Sneed and Watson, Nicklaus missing out by a shot. (Herb Wind’s account reads like a thriller.) Big Jack was at his peak, and Arnold was still at it. Trevino won the Canadian Open in ’79. Younger players—Tom Watson, Seve Ballesteros, Ben Crenshaw—were taking over center stage. Watson was a latter-day Huck Finn with a Stanford degree. Seve was a Spanish artiste. Crenshaw was a matinee idol. The low amateur at the ’79 U.S. Open at Inverness was Fred Couples, in his first U.S. Open. Curtis Strange, already famous for his collegiate play, won his first tour event in ’79.

I would like to point out that my legends have nothing to do with the modern penchant for celebrity worship. You can become a celebrity overnight. My legends have a serious body of work behind them. John Updike, referring to Ted Williams, famously wrote, “Gods don’t answer letters.” No, they don’t.

The Ted Williams reference (you may know) relates to his refusal to take a curtain call after the final at-bat of his career, a home run into the Red Sox bullpen at Fenway. Williams courted nobody. Why would he need the Boston baseball writers when he owned the box scores? Maybe a piece of his humanity got robbed along the way, going through life the way he did. If you read the books about him, it sounds that way. Regardless, his lifetime batting average was .344. You can’t have everything.

Tiger Woods has some Williams in him. He’ll look right through you. I started covering Tiger when he was an amateur, and it’s been an honor, writing up his golfing exploits. I am well north of a quarter-million words on Woods and counting. What luck: I was able to write about one of the most dominating athletic careers ever as it unfolded. Still, I would have enjoyed it much more had there been expressions of warmth from the man, hints of humility. I wish he would acknowledge that the game has given him far more than he could ever give it. Maybe he doesn’t think that—I wouldn’t know. One of my goals here is to see for myself whether Arnold and Jack and the rest really put the game ahead of themselves, or if that was a myth handed down to me by sportswriters happy to god-up the ballplayers.

Only a fool would try to dismiss what Woods has accomplished. (The most common method is to diminish his competition.) When Woods won the 2008 U.S. Open at Torrey Pines, that was his fourteenth major, and he was only thirty-two. Who wouldn’t want to write up all that?

But I can say without even pausing that writing about other golfing lives has been far more meaningful to me. Arnold and Nicklaus and Watson spring right to mind, though I arrived on the scene long after their Cold War heydays. Collectively, they owned about thirty years of American golf, starting in ’58, three decades when Tom Carvel was the voice of summer and you could play street hockey with his rock-hard Flying Saucers.

While we’re kicking this theme around, I should explain the concept of Secret Legends: your Mike Donalds, your Neil Oxmans, your Billy Harmons. We all have our own, and here are others from my catalog: Hilome Jose, a Haitian artist; the guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, whom I have heard dozens of times; Ed Landers, a Martha’s Vineyard fisherman discussed with hushed awe when I lived there. All men devoted to doing a difficult thing well. Craftsmen. You surely have a list of your own.

You probably don’t know the name Joe Gergen. Joe Gergen was a sportswriter and columnist on Newsday when I was a kid. He covered the Mets, the Jets, the Knicks, and the Rangers, and he wrote like a dream. At the 1986 U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills, typewriters dying but not yet dead, I sat behind Gergen in the press tent. On U.S. Open Sunday he wore a colorful short-sleeve shirt patterned with flowers, and he wrote up Raymond Floyd’s win with one guy on his left elbow and another on his right. Three writers on deadline, and every five minutes they tilted their heads and laughed about something. It was Father’s Day. Do you think he minded working? Not one bit. His story in the next day’s paper was excellent, and I wanted to be him. Joe Gergen is not likely a legend to you. Why would he be? But he is to me. I’d die without people like that in my head.

• • •

A note here about Mike Donald, the legend with whom I have the most personal history. I met Mike in 1985, when he was playing in the Honda Classic and was paired with Brad Faxon, for whom I was caddying. Over the next six months—as a fledgling caddie with a plan to write my first book—I saw Mike here and there. My boss, Bill Britton, would play in practice rounds with Mike, one of his closest friends. Or they’d hit balls and look at each other’s swings. Or I’d see Mike on Friday afternoons, standing in front of that week’s giant scoreboard, pointing at names, counting scores, calculating where the ax—the cut number—would fall. His nickname was Statman.

In ’86, I caddied for Mike for one memorable week, at the Colonial tournament in Fort Worth. That week was a semi-disaster and included a mortifying rules question for which I was responsible. All in all, not my best week. My main purpose in Fort Worth was to promote the aforementioned book. I should have told Mike that when I sought his bag for the week. I now realize the week was doomed before I even arrived. It’s embarrassing for me, looking back at it. Talk about young and dumb.

By the high standards of tour play, Mike was considered average in every category except three: chipping, putting, and intensity. In ’89, after playing in more than three hundred tour events and having posted more than twenty top-ten finishes, he won the Williamsburg stop, the Anheuser-Busch Golf Classic. He was thirty-four and had his first tour win.

That win got Mike into the Masters for the first time, the following April. He shot an opening-round 64 in the ’90 Masters, one shot short of tying the course record. Two months later, Mike played in the U.S. Open at Medinah. Hale Irwin shot a final-round 67 to come in at 280. About two hours later, in the final group of the day, Mike made a par on the seventy-second hole to post 280 as well. Their Sunday-night tie meant an eighteen-hole playoff the next day. After those eighteen holes they were still tied, which meant for the first time a U.S. Open would be decided by so-called sudden death. The next winner of a hole would be the champ. Mike and Hale went to the first tee for the ninety-first hole of the championship.

I can’t imagine anybody (outside of Hale Irwin’s immediate family) not pulling for Mike in that playoff. He was the classic underdog, and who doesn’t cheer for an underdog? Hale Irwin was already in the pantheon, by way of his ’74 and ’79 U.S. Open wins. What Irwin was attempting to do, at age forty-five, was impressive. But it paled in comparison to Mike’s quest. In the 1955 Open, Jack Fleck, a club pro from a public course in Iowa, defeated the great Hogan in a playoff. Mike was another lunch-bucket pro trying to knock off a legend in the most demanding event in golf.

I was working that Sunday, covering a Phillies matinee, and watched good chunks of the fourth round in the manager’s office at Veterans Stadium. I watched the Monday final at home on a day off. What Mike did that day was raise expectations, for himself or anyone with middling skills, in any trade or craft or profession. Watching Mike made you realize that past performance really doesn’t always predict future results. Mike was going toe to toe with Hale Irwin! All the while, watching the events unfold on ABC, we could not know that the best was still to come: Mike in defeat. There was a moment at the end of the playoff that screamed at me. Irwin made a twelve-foot birdie putt to win. He had his third Open. He had become the oldest player ever to win an Open. He was dancing around. And there was Mike, holding out a hand in a manner that was just so . . . dignified.

Our friendship began for real five years later, when I was writing a piece about him. Mike told me about accepting an offer to play in Sweden soon after that U.S. Open for a thirty-five-thousand-dollar appearance fee and all expenses paid for Mike and his parents. “To be honest, I felt like a whore,” Mike told me with my notebook open. Who is that honest? After the ’90 U.S. Open, he never revisited that level of play. I sat amazed, with the five-year anniversary coming up, as Mike tried to analyze what had happened to his game and to him.

Had Mike won in ’90, I’m sure our friendship never would have developed as it did. You can’t have a real friendship with a winner. You come into a person’s life after the prize ceremony, you’ll always be a Johnny-come-lately. I expressed this to Mike once, and he said, “If I had won, you wouldn’t have been interested in writing about me.” He’s probably right. At SI, my assignment is often to write the loser. I like it.

Mike played the circuit hard, as hard as anybody. For years he played thirty to thirty-five events a year. He had a true grasp of the tour and how it worked, and the other players knew it. Even though he never finished higher than twenty-second on the annual money list, he was at the center of the game. Tiger Woods drops in and drops out when it suits him. Phil Mickelson, Ernie Els, Rory McIlroy, they all do that. Mike was on tour. He was at-large.

In various ways, we could not be more different. I am trusting and Mike is suspicious. Yet Mike tends to overshare and I underdo it. He watches everything and I read, too narrowly. He understands the stock market in ways that I do not. He is profane and I’m not, or at least not at Mike’s level. I see gray in everything and Mike tries to see things in black or white. Mike likes the windows up and I like them down. But we have significant similarities, too. We’re both good tippers. We both have good memories. We both like to try to figure things out.

When he was fifteen, Mike skipped school and caddied in the 1970 Coral Springs Open, near his home in Hollywood, in South Florida. He can tell you what Hale Irwin and Lee Trevino did that week and that Palmer stayed in a house on the course sponsored by Westinghouse known as “The House of the Future.” (You could turn a light on and off in it by waving your arms.) Mike remembers Palmer wearing a baby-blue shirt with dark-brown pants and wondering whether that was a good match. He of course remembers who won: Bill Garrett. Mike was his caddie, and Garrett paid Mike a fortune.

I once asked Mike, “Did you do anything to help Garrett at all?”

“Noooooooo,” Mike said. “Shit no. I carried the bag!”

One day I was looking at my legends list and thinking about the start of my tour. What the hell was I actually looking to do? Write something longer than six hundred words. Explore friendship. Have an adventure. Try to understand the lives and times of craftsmen I admired. Rekindle my boyhood excitement.

As a reporter I work solo. It’s a rewarding and lonesome way to proceed. I’m not even sure why, but one day I found myself asking Mike if he wanted to join me on the tour’s first stop. I would have asked him if he wanted to sign up for the whole thing, but Mike, like me, avoids commitment. Plus, I couldn’t know if there would be a whole thing. Anyway, we both do most everything on the fly. We’ve had many excellent meals, rounds of golf, and ballgames over the years with little advance planning, if any.

Mike said yes. No questions, just yes. He caught a flight to Philadelphia, and we hopped in my car and drove clear across Pennsylvania, off to see Arnold Palmer, in Latrobe. You got to start somewhere, right?

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 5, 2016)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476743837

Raves and Reviews

“Maybe the best golf book I’ve ever read.” —Bill Reynolds, The Providence Journal

"This is the golf version of Roger Kahn's classic The Boys of Summer." —Chicago Tribune

“Until roughly the mid-1980s, the PGA Tour really was a tour, not the geographically-dispersed collection of big-money events that it is today. The players and often their wives drove from event to event or hopped on chartered flights together. . . . In a new book, Men in Green, author Michael Bamberger re-creates that tour through a series of surprisingly candid interviews with players, caddies, wives, and others who were there. It is a world of booze-fueled friendships and feuds, of deep bonds and annoyances, of hurts that still fester and memories that still glow. Braiding it all together is the power and addiction of golf. . . . Bamberger doesn’t flinch at portraying the Tour’s earthier aspects. Drugs, sex, and alcohol, although not sensationalized, take their appropriate place in his narrative. But the book is overwhelmingly a love song. . . . Above all, what comes through is the sense of the Tour back then as an extended family, sometimes dysfunctional but never dull.” —John Paul Newport, The Wall Street Journal

“Michael Bamberger is a hard-boiled reporter with a sly wit, but his bottom-line virtue is empathy. That’s made him the most penetrating and insightful golf writer of our time. Men in Green is Bamberger at his best: revealing secrets, puncturing myths, adjudicating never-settled feuds. His new book has the suspenseful urgency of a detective novel, a cast of characters out of a Fellini movie, and the heart of a Charlie Brown Christmas special. If I could have only one golf book on a deserted island, Men in Green would be that book.”

—John Garrity, author of Ancestral Links

“Men in Green is peppered with appealing vignettes—such as Billy Harmon on what Bob Goalby said to himself standing over a four-foot putt on the last hole of the 1968 Masters—but Bamberger has a higher purpose. Identifying legends and trying to find out what makes them tick, he and Donald provide exceptional insight into some of America’s greatest players over the last half-century.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer

“To be cherished . . . Will entertain and enthrall . . . A nostalgic visit and reminiscence with those who fashioned golf history.” —Golf Digest

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Men in Green Trade Paperback 9781476743837

- Author Photo (jpg): Michael Bamberger Matt Ginella(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit