Table of Contents

About The Book

In a dramatic, moving work of historical reporting and personal discovery, Mark Whitaker, award-winning journalist, sets out to trace the story of what happened to his parents, a fascinating but star-crossed interracial couple, and arrives at a new understanding of the family dramas that shaped their lives—and his own.

His father, “Syl” Whitaker, was the charismatic grandson of slaves who grew up the child of black undertakers from Pittsburgh and went on to become a groundbreaking scholar of Africa. His mother, Jeanne Theis, was a shy World War II refugee from France whose father, a Huguenot pastor, helped hide thousands of Jews from the Nazis and Vichy police. They met in the mid-1950s, when he was a college student and she was his professor, and they carried on a secret romance for more than a year before marrying and having two boys. Eventually they split in a bitter divorce that was followed by decades of unhappiness as his mother coped with self-recrimination and depression while trying to raise her sons by herself, and his father spiraled into an alcoholic descent that destroyed his once meteoric career.

Based on extensive interviews and documentary research as well as his own personal recollections and insights, My Long Trip Home is a reporter’s search for the factual and emotional truth about a complicated and compelling family, a successful adult’s exploration of how he rose from a turbulent childhood to a groundbreaking career, and, ultimately, a son’s haunting meditation on the nature of love, loss, identity, and forgiveness.

His father, “Syl” Whitaker, was the charismatic grandson of slaves who grew up the child of black undertakers from Pittsburgh and went on to become a groundbreaking scholar of Africa. His mother, Jeanne Theis, was a shy World War II refugee from France whose father, a Huguenot pastor, helped hide thousands of Jews from the Nazis and Vichy police. They met in the mid-1950s, when he was a college student and she was his professor, and they carried on a secret romance for more than a year before marrying and having two boys. Eventually they split in a bitter divorce that was followed by decades of unhappiness as his mother coped with self-recrimination and depression while trying to raise her sons by herself, and his father spiraled into an alcoholic descent that destroyed his once meteoric career.

Based on extensive interviews and documentary research as well as his own personal recollections and insights, My Long Trip Home is a reporter’s search for the factual and emotional truth about a complicated and compelling family, a successful adult’s exploration of how he rose from a turbulent childhood to a groundbreaking career, and, ultimately, a son’s haunting meditation on the nature of love, loss, identity, and forgiveness.

Appearances

MAY 17

15:00:00

in person

Politics & Prose

In Person

3pm ET, moderator: Eugene Robinson of the Washington Post and MSNBC

5015 Connecticut Ave NW Downstairs

Washington, DC 20008

MAY 19

19:00:00

in person

Reading Group Guide

This reading group guide for My Long Trip Home includes an introduction, discusMark WhitakerChris Cleave. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book.

Introduction

In My Long Trip Home, Mark Whitaker, a renowned journalist and editor with over thirty years of experience reporting on the world around him, turns his eagle eye inward. My Long Trip Home traces the fascinating paths of Mark’s parents and grandparents, from the French countryside during World War II to segregated, wartime Pittsburgh, before settling in with his own personal story. Mark’s father, Syl, struggled mightily with alcoholism and anger issues; Mark’s mother, Jeanne, wrestled with depression and financial hardship raising two young sons on her own; and Mark spent much of his childhood angry at his parents for separating, and confused by their bitter divorce. But after years of emotional turmoil, Mark began to make peace with his family’s past, doing so in time to have one last meaningful visit with his father before his death. In this family memoir, Mark explores and retreads the many paths that converged to create his own life, and discovers the healing power of forgiveness and compassion along the way.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

Topics & Questions for Discussion 1. Mark Whitaker is a journalist by profession. In what ways did his journalistic instincts come through in My Long Trip Home?

2. How was the narrative in My Long Trip Home enhanced by first exploring the family history of both of Mark’s parents? How would the story have been different if Whitaker had only written about his own life?

3. Why do you think Whitaker wrote this memoir?

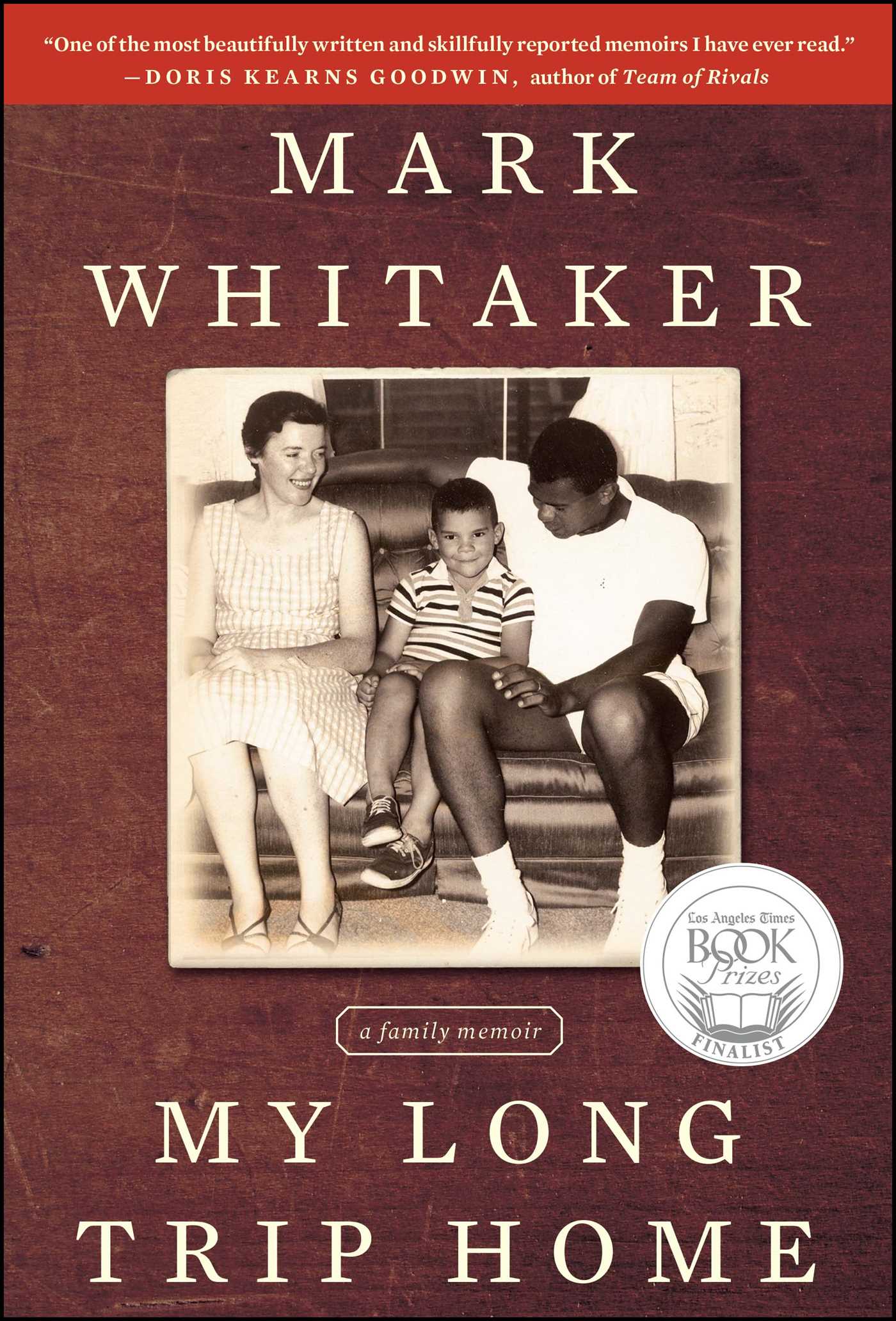

4. How did the photos affect your experience of reading My Long Trip Home? Did you feel differently toward people described in the book after seeing their photos?

5. My Long Trip Home is, in many ways, a story of American history as well as familial history. How did important movements and events in American history alter the trajectory of the Whitaker and Theis families?

6. Syl was a great charmer and a wonderful conversationalist. What were the hidden downsides of these outwardly positive traits?

7. Whitaker doesn’t express much self-pity, but by all accounts he had a difficult childhood and adolescence. What coping mechanisms did he use to get through the hard parts of his life?

8. How did Whitaker’s understanding of race, and of his racial identity, shift as he grew up? What role did his father play in shaping his racial identity? His mother? Reflect on your own adolescence. How did your racial identity shape you as a person?

9. How did racism—both subtle and overt—shape and influence C.S., Edith, Syl, and Mark’s careers? Have you ever been confronted with racism in your personal or professional life?

10. How did Whitaker express his anger throughout the years? How did his feelings towards his father evolve as he grew older?

11. Syl once told his son: “Human nature is to abuse power…most people who abuse power don’t think they are doing it. They’ve justified it based on their own view of the world.” (p. 285) Do you think Syl abused power? In what ways? What was Syl’s own view of the world that enabled him to justify the abuses?

12. Geraldine Owen Delaney, the head of Alina Lodge, said that “of all the ways alcoholics fooled themselves, the greatest delusion was control.” (p. 219) How did this delusion of control manifest itself in Syl’s life? Why do you think Syl finally stopped drinking?

13. How did feminism and the women’s movement impact Whitaker’s mother? If you were alive during the feminist movement in the 1970s, were you reminded of anything from your own personal experiences? How do you define feminism?

14. Both the Whitaker and Theis families have legacies of heroism and strength in the face of adversity. In what ways did Jeanne, Syl, and Mark carry on those legacies?

15. What factors—emotional, familial, genetic, situational—do you think contributed to Whitaker’s success in life? What forces and people helped him as a person?

16. In describing his motivation for leaving Swarthmore, Whitaker writes: “Just as I had been at George School, I was driven by a desire to find something—I didn’t know exactly what—that I thought I was missing.” (p. 182) What do you think he was missing? Did he ever find it?

17. Is there a hero or heroine in My Long Trip Home? Why or why not? If yes, who do you think it is?

18. When Mark’s parents learned that he wanted to write a book about their family, his mother expressed concerns that “the story would make me look very weak,” and his father said, “I don’t want to be the villain of the piece.” (p. 335) Do you think Mark successfully honored each of their wishes? Why or why not? Do you think his parents would feel that they were accurately depicted?

19. How different would the Whitaker family story play out if Whitaker’s parents met as young adults today? Consider the effects of the civil rights and women’s rights movements on our current culture and society.

20. Whitaker writes, of his time spent in France as a teenager: “I was learning something even more important that year: that not all families are destined to be unhappy.” (p. 276) Do you think families are destined to be happy or unhappy? How can you choose happiness as a family?

21. According to Whitaker, during Syl’s tenure at Princeton, he would focus discussions and dissuade distractions in meetings by asking, “But what is the noble purpose?” (p. 169) What do you think is the “noble purpose” of My Long Trip Home?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. My Long Trip Home is, among many things, an exercise in meticulous genealogical research. Take a moment to reflect on a family story or memory that makes you smile, and do a bit of digging. Who are the characters in this memory? Do you tell this story often? If you have access, look through old photographs, letters, postcards, or journals for supporting evidence, and bring your finds to book club. If you’re able to speak with an older relative, ask them about their favorite family stories as well. Did you uncover anything surprising about your past? What qualities or traits in your family history do you most admire? For reference, consult the author’s own suggestions for genealogical research (www.cnn.com/2011/10/17/opinion/whitaker-family-story/index) and the National Archives’ genealogical research tools and tips (www.archives.gov/research/genealogy/index).

2. Mark Whitaker has had a long and distinguished career as a journalist and editor. Get a behind-the-scenes look at the journalism industry by scheduling a newsroom tour with your local TV news affiliate. How did the tour change your perception of journalism and TV news? What types of people do you think thrive in that environment? Do you feel differently about Whitaker after learning more about his profession?

3. Mark’s family has strong French and African ties. Explore both cultures in the most delicious way possible: Food! Host an international potluck for your book club by preparing dishes from France and Nigeria, as well as any other countries you have a personal connection to. Consult www.epicurious.com/recipesmenus/global/recipes for more recipe and dish ideas.

4. Both Syl and Mark benefited from scholarships during their college years. Get into the spirit of supporting education, and volunteer to read to children at a local school or through a charity near you. Visit www.reachoutandread.org for more information.

5. In My Long Trip Home retraces history and shares family stories from earlier generations. Look forward and imagine your descendants want to write about your life. What personal story would you want to pass down to them? Share your story with your book club. Do any common themes emerge?

A Conversation with Mark Whitaker

You explained in an interview that, though you were initially ashamed by the unpleasant aspects of your family history, “Once I’d embarked on the book, I found that coming to it as a reporter gave me a kind of detachment that I needed.” Did you ever try to write this memoir with more of a visceral, emotional connection? What made you decide to approach your family’s story with a reporter’s detachment?

I started writing the story from memory, because that’s what I thought you did as a memoirist. But I quickly realized that there were many things about my family’s story that I didn’t know, or thought I knew but wasn’t sure if I had right. That’s when I began approaching the story as a reporter—interviewing sources, collecting documents, verifying details. Because that’s what I’ve been trained to do, it made the project much easier and more enjoyable for me. But I think it also made it easier for people to talk to me, particularly in revisiting the painful episodes, because they could see that I wasn’t trying to judge anyone but to search for the truth.

You did an enormous amount of research for this memoir. What discoveries most surprised and thrilled you? What information did you find most disappointing or frustrating?

My most pleasant discoveries were about my grandparents and my grandfathers in particular. I learned that my father’s father, who I knew as a stroke victim late in his life, was an incredibly dynamic man who had born on a tenant farm in Texas, the eleventh child of a former slave, and risen by force of will and personality to became one of Pittsburgh’s first black undertakers. I also learned more about the heroism of my mother’s father, a French Protestant pastor who helped hide Jews from the Nazis during World War II. My saddest discoveries were about my father—not just the extent of his alcoholism, in the years when I didn’t see him much, but how needlessly unforgiving he was to so many people in his life.

In any memoir that requires detailed recounting of the past, the author’s memory (and that of his subjects) is truly put to the test. How much, if any, of your story came from assumptions, rather than concrete evidence? Do you feel your journalistic instinct for a fact-based narrative altered your writing style in any way?

In many ways, the narrative voice of the book comes from that disparity between what I remembered or assumed and what I discovered in the course of my reporting. It’s there in the first paragraph of the first chapter—“Growing up, I always took it for granted that it was my mother who was first attracted to my father… But when I went back and investigated, it turned out that it was the other way around....” And that interweaving of memory and reporting continues throughout the book.

You mentioned in an interview on “The Colbert Report” that you wrote this book without an advance or any publisher’s commitment. Was your final goal to always publish this memoir, or did you initially write the manuscript for your own satisfaction?

I started writing a year to the day after my father died, after waking up in the middle of the night with an epiphany that I wanted to tell his story. At first I just wanted to see what came out, and I wasn’t sure if it would add up to a book that anyone else would find interesting. Once I had written 200 pages, I sent it to a literary agent friend, and she suggested that I finish a first draft before submitting it to publishers. So I didn’t know for sure that it would be published until that first draft was finished, at which point I rewrote the whole thing twice to make sure that it would also be a satisfying experience for readers who didn’t know me.

What was it like to share My Long Trip Home with your family for the first time? What do you think your father would say about this book?

I interviewed all the surviving members of my family at length for the book: my mother and my brother and my father’s older sister, among others. So none of them were surprised about what I said about them, although they all learned other family details they had never known before. They were all very supportive, although my mother in particular was a stickler for accuracy. What would my father have thought? I hope he would have understood that ultimately the book is meant as a tribute to him and to my mother, and that he would have been proud to have a record of all of us for posterity. But he could be very thin-skinned and argumentative, so I’m sure there are many details with which he would have quibbled.

Why do you think you suddenly felt ready to write this book when you did, a year to the day after your father died? What kept you from writing it earlier?

For many years, I told myself that I was too busy with my career to write a book. But the truth is that I was also ashamed. I thought that the only part worthy of a book was the romantic part—the interracial romance, the talks of black Pittsburgh and the French Resistance. Yet I also thought it would be dishonest to leave out the painful part after my parents divorced. Of course, now that it’s done I see that it’s the pain and recovery and reconciliation that most people relate to, and that makes the story universal.

What traits or qualities are you most proud of in your mother and father? What important lessons did they give to you that you hope to pass on to your children?

Ultimately, the book is about what I got from both of my parents, not just what I didn’t get. From both of them, I inherited a reverence for learning, and love of language and writing. From my father, I learned a wry skepticism about human nature and institutions and some of the positive as well as negative virtues of social charisma and charm. From my mother, I inherited a basic survival instinct and a faith in myself that started with her faith in me. Of all those gifts, that last one is the one I have most wanted to pass on to my own children.

If you could go back in time and visit your younger self, what would you say to your 10-year-old self?

I would have told my ten-year old self: it’s not always going to be this bad! You won’t always be fat. You’ll get to see your father again, and he will eventually have a place in your life. Your horizons won’t be limited to this little town where you’re living now. Your mother will get happier. You won’t always fight with your brother. In fact, you have a lot to look forward to! You are going to have a very rich and full life and a happy family of your own some day. And that all turned out to be true, although I’m not sure I would have believed it at the time.

You said in an interview with Reuters, “I wanted to prove myself on my own, both vis-à-vis my parents and my race.” Do you think your children feel the same way?

Absolutely, and my wife and I encourage that. We thought it was important for our two children to learn about their black and Jewish heritage, because they are both by birthright. But we also made it clear that as adults, they would be free to forge their own identities, and to associate with the friends and mates and communities they choose for themselves. And so far I think they’ve made very sound choices in that regard. But I also think that children of interracial and interreligious backgrounds are a lot more common and accepted than they were in the past, and that’s a good thing.

What advice do you have for people struggling to overcome a turbulent childhood or a difficult family situation? Was writing and researching a form of therapy for you?

This is easier said than done, but I would say that you may not be able to change the past, but can choose what to make of it. Since I believe in “show, don’t tell,” what I tried to show in the book was that you can take responsibility for your own life, and try to understand your parents on their own terms and not just in terms of what they did to you. And for me, that was a very therapeutic exercise: to see them almost as characters in a novel, shaped by their own family dramas, their own experience or lack of experience, and the historical places and periods they inhabited.

Do you think happiness is a destiny or a choice? How do you strive for happiness in your own family?

I’m not Pollyanna, so I don’t believe you can choose to feel happy all the time. But I do think you can make choices that will make your life happier over time. I consciously chose a career that I enjoyed, rather than just one that would be lucrative. I married a woman who made me laugh and could cheer me up when I was down. I made spending time with my children a high priority despite my busy job because that brought me pleasure. I’ve been very lucky along the way, both professionally and personally, but I believe that you can help make your own luck if you know what you’re looking for and are grateful when you find it.

Introduction

In My Long Trip Home, Mark Whitaker, a renowned journalist and editor with over thirty years of experience reporting on the world around him, turns his eagle eye inward. My Long Trip Home traces the fascinating paths of Mark’s parents and grandparents, from the French countryside during World War II to segregated, wartime Pittsburgh, before settling in with his own personal story. Mark’s father, Syl, struggled mightily with alcoholism and anger issues; Mark’s mother, Jeanne, wrestled with depression and financial hardship raising two young sons on her own; and Mark spent much of his childhood angry at his parents for separating, and confused by their bitter divorce. But after years of emotional turmoil, Mark began to make peace with his family’s past, doing so in time to have one last meaningful visit with his father before his death. In this family memoir, Mark explores and retreads the many paths that converged to create his own life, and discovers the healing power of forgiveness and compassion along the way.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

Topics & Questions for Discussion 1. Mark Whitaker is a journalist by profession. In what ways did his journalistic instincts come through in My Long Trip Home?

2. How was the narrative in My Long Trip Home enhanced by first exploring the family history of both of Mark’s parents? How would the story have been different if Whitaker had only written about his own life?

3. Why do you think Whitaker wrote this memoir?

4. How did the photos affect your experience of reading My Long Trip Home? Did you feel differently toward people described in the book after seeing their photos?

5. My Long Trip Home is, in many ways, a story of American history as well as familial history. How did important movements and events in American history alter the trajectory of the Whitaker and Theis families?

6. Syl was a great charmer and a wonderful conversationalist. What were the hidden downsides of these outwardly positive traits?

7. Whitaker doesn’t express much self-pity, but by all accounts he had a difficult childhood and adolescence. What coping mechanisms did he use to get through the hard parts of his life?

8. How did Whitaker’s understanding of race, and of his racial identity, shift as he grew up? What role did his father play in shaping his racial identity? His mother? Reflect on your own adolescence. How did your racial identity shape you as a person?

9. How did racism—both subtle and overt—shape and influence C.S., Edith, Syl, and Mark’s careers? Have you ever been confronted with racism in your personal or professional life?

10. How did Whitaker express his anger throughout the years? How did his feelings towards his father evolve as he grew older?

11. Syl once told his son: “Human nature is to abuse power…most people who abuse power don’t think they are doing it. They’ve justified it based on their own view of the world.” (p. 285) Do you think Syl abused power? In what ways? What was Syl’s own view of the world that enabled him to justify the abuses?

12. Geraldine Owen Delaney, the head of Alina Lodge, said that “of all the ways alcoholics fooled themselves, the greatest delusion was control.” (p. 219) How did this delusion of control manifest itself in Syl’s life? Why do you think Syl finally stopped drinking?

13. How did feminism and the women’s movement impact Whitaker’s mother? If you were alive during the feminist movement in the 1970s, were you reminded of anything from your own personal experiences? How do you define feminism?

14. Both the Whitaker and Theis families have legacies of heroism and strength in the face of adversity. In what ways did Jeanne, Syl, and Mark carry on those legacies?

15. What factors—emotional, familial, genetic, situational—do you think contributed to Whitaker’s success in life? What forces and people helped him as a person?

16. In describing his motivation for leaving Swarthmore, Whitaker writes: “Just as I had been at George School, I was driven by a desire to find something—I didn’t know exactly what—that I thought I was missing.” (p. 182) What do you think he was missing? Did he ever find it?

17. Is there a hero or heroine in My Long Trip Home? Why or why not? If yes, who do you think it is?

18. When Mark’s parents learned that he wanted to write a book about their family, his mother expressed concerns that “the story would make me look very weak,” and his father said, “I don’t want to be the villain of the piece.” (p. 335) Do you think Mark successfully honored each of their wishes? Why or why not? Do you think his parents would feel that they were accurately depicted?

19. How different would the Whitaker family story play out if Whitaker’s parents met as young adults today? Consider the effects of the civil rights and women’s rights movements on our current culture and society.

20. Whitaker writes, of his time spent in France as a teenager: “I was learning something even more important that year: that not all families are destined to be unhappy.” (p. 276) Do you think families are destined to be happy or unhappy? How can you choose happiness as a family?

21. According to Whitaker, during Syl’s tenure at Princeton, he would focus discussions and dissuade distractions in meetings by asking, “But what is the noble purpose?” (p. 169) What do you think is the “noble purpose” of My Long Trip Home?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. My Long Trip Home is, among many things, an exercise in meticulous genealogical research. Take a moment to reflect on a family story or memory that makes you smile, and do a bit of digging. Who are the characters in this memory? Do you tell this story often? If you have access, look through old photographs, letters, postcards, or journals for supporting evidence, and bring your finds to book club. If you’re able to speak with an older relative, ask them about their favorite family stories as well. Did you uncover anything surprising about your past? What qualities or traits in your family history do you most admire? For reference, consult the author’s own suggestions for genealogical research (www.cnn.com/2011/10/17/opinion/whitaker-family-story/index) and the National Archives’ genealogical research tools and tips (www.archives.gov/research/genealogy/index).

2. Mark Whitaker has had a long and distinguished career as a journalist and editor. Get a behind-the-scenes look at the journalism industry by scheduling a newsroom tour with your local TV news affiliate. How did the tour change your perception of journalism and TV news? What types of people do you think thrive in that environment? Do you feel differently about Whitaker after learning more about his profession?

3. Mark’s family has strong French and African ties. Explore both cultures in the most delicious way possible: Food! Host an international potluck for your book club by preparing dishes from France and Nigeria, as well as any other countries you have a personal connection to. Consult www.epicurious.com/recipesmenus/global/recipes for more recipe and dish ideas.

4. Both Syl and Mark benefited from scholarships during their college years. Get into the spirit of supporting education, and volunteer to read to children at a local school or through a charity near you. Visit www.reachoutandread.org for more information.

5. In My Long Trip Home retraces history and shares family stories from earlier generations. Look forward and imagine your descendants want to write about your life. What personal story would you want to pass down to them? Share your story with your book club. Do any common themes emerge?

A Conversation with Mark Whitaker

You explained in an interview that, though you were initially ashamed by the unpleasant aspects of your family history, “Once I’d embarked on the book, I found that coming to it as a reporter gave me a kind of detachment that I needed.” Did you ever try to write this memoir with more of a visceral, emotional connection? What made you decide to approach your family’s story with a reporter’s detachment?

I started writing the story from memory, because that’s what I thought you did as a memoirist. But I quickly realized that there were many things about my family’s story that I didn’t know, or thought I knew but wasn’t sure if I had right. That’s when I began approaching the story as a reporter—interviewing sources, collecting documents, verifying details. Because that’s what I’ve been trained to do, it made the project much easier and more enjoyable for me. But I think it also made it easier for people to talk to me, particularly in revisiting the painful episodes, because they could see that I wasn’t trying to judge anyone but to search for the truth.

You did an enormous amount of research for this memoir. What discoveries most surprised and thrilled you? What information did you find most disappointing or frustrating?

My most pleasant discoveries were about my grandparents and my grandfathers in particular. I learned that my father’s father, who I knew as a stroke victim late in his life, was an incredibly dynamic man who had born on a tenant farm in Texas, the eleventh child of a former slave, and risen by force of will and personality to became one of Pittsburgh’s first black undertakers. I also learned more about the heroism of my mother’s father, a French Protestant pastor who helped hide Jews from the Nazis during World War II. My saddest discoveries were about my father—not just the extent of his alcoholism, in the years when I didn’t see him much, but how needlessly unforgiving he was to so many people in his life.

In any memoir that requires detailed recounting of the past, the author’s memory (and that of his subjects) is truly put to the test. How much, if any, of your story came from assumptions, rather than concrete evidence? Do you feel your journalistic instinct for a fact-based narrative altered your writing style in any way?

In many ways, the narrative voice of the book comes from that disparity between what I remembered or assumed and what I discovered in the course of my reporting. It’s there in the first paragraph of the first chapter—“Growing up, I always took it for granted that it was my mother who was first attracted to my father… But when I went back and investigated, it turned out that it was the other way around....” And that interweaving of memory and reporting continues throughout the book.

You mentioned in an interview on “The Colbert Report” that you wrote this book without an advance or any publisher’s commitment. Was your final goal to always publish this memoir, or did you initially write the manuscript for your own satisfaction?

I started writing a year to the day after my father died, after waking up in the middle of the night with an epiphany that I wanted to tell his story. At first I just wanted to see what came out, and I wasn’t sure if it would add up to a book that anyone else would find interesting. Once I had written 200 pages, I sent it to a literary agent friend, and she suggested that I finish a first draft before submitting it to publishers. So I didn’t know for sure that it would be published until that first draft was finished, at which point I rewrote the whole thing twice to make sure that it would also be a satisfying experience for readers who didn’t know me.

What was it like to share My Long Trip Home with your family for the first time? What do you think your father would say about this book?

I interviewed all the surviving members of my family at length for the book: my mother and my brother and my father’s older sister, among others. So none of them were surprised about what I said about them, although they all learned other family details they had never known before. They were all very supportive, although my mother in particular was a stickler for accuracy. What would my father have thought? I hope he would have understood that ultimately the book is meant as a tribute to him and to my mother, and that he would have been proud to have a record of all of us for posterity. But he could be very thin-skinned and argumentative, so I’m sure there are many details with which he would have quibbled.

Why do you think you suddenly felt ready to write this book when you did, a year to the day after your father died? What kept you from writing it earlier?

For many years, I told myself that I was too busy with my career to write a book. But the truth is that I was also ashamed. I thought that the only part worthy of a book was the romantic part—the interracial romance, the talks of black Pittsburgh and the French Resistance. Yet I also thought it would be dishonest to leave out the painful part after my parents divorced. Of course, now that it’s done I see that it’s the pain and recovery and reconciliation that most people relate to, and that makes the story universal.

What traits or qualities are you most proud of in your mother and father? What important lessons did they give to you that you hope to pass on to your children?

Ultimately, the book is about what I got from both of my parents, not just what I didn’t get. From both of them, I inherited a reverence for learning, and love of language and writing. From my father, I learned a wry skepticism about human nature and institutions and some of the positive as well as negative virtues of social charisma and charm. From my mother, I inherited a basic survival instinct and a faith in myself that started with her faith in me. Of all those gifts, that last one is the one I have most wanted to pass on to my own children.

If you could go back in time and visit your younger self, what would you say to your 10-year-old self?

I would have told my ten-year old self: it’s not always going to be this bad! You won’t always be fat. You’ll get to see your father again, and he will eventually have a place in your life. Your horizons won’t be limited to this little town where you’re living now. Your mother will get happier. You won’t always fight with your brother. In fact, you have a lot to look forward to! You are going to have a very rich and full life and a happy family of your own some day. And that all turned out to be true, although I’m not sure I would have believed it at the time.

You said in an interview with Reuters, “I wanted to prove myself on my own, both vis-à-vis my parents and my race.” Do you think your children feel the same way?

Absolutely, and my wife and I encourage that. We thought it was important for our two children to learn about their black and Jewish heritage, because they are both by birthright. But we also made it clear that as adults, they would be free to forge their own identities, and to associate with the friends and mates and communities they choose for themselves. And so far I think they’ve made very sound choices in that regard. But I also think that children of interracial and interreligious backgrounds are a lot more common and accepted than they were in the past, and that’s a good thing.

What advice do you have for people struggling to overcome a turbulent childhood or a difficult family situation? Was writing and researching a form of therapy for you?

This is easier said than done, but I would say that you may not be able to change the past, but can choose what to make of it. Since I believe in “show, don’t tell,” what I tried to show in the book was that you can take responsibility for your own life, and try to understand your parents on their own terms and not just in terms of what they did to you. And for me, that was a very therapeutic exercise: to see them almost as characters in a novel, shaped by their own family dramas, their own experience or lack of experience, and the historical places and periods they inhabited.

Do you think happiness is a destiny or a choice? How do you strive for happiness in your own family?

I’m not Pollyanna, so I don’t believe you can choose to feel happy all the time. But I do think you can make choices that will make your life happier over time. I consciously chose a career that I enjoyed, rather than just one that would be lucrative. I married a woman who made me laugh and could cheer me up when I was down. I made spending time with my children a high priority despite my busy job because that brought me pleasure. I’ve been very lucky along the way, both professionally and personally, but I believe that you can help make your own luck if you know what you’re looking for and are grateful when you find it.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (October 18, 2011)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781451627565

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): My Long Trip Home eBook 9781451627565

- Author Photo (jpg): Mark Whitaker © Jennifer S. Altman(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit