LIST PRICE $18.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Sally Ride was more than the first woman in space—she was a real-life explorer and adventurer whose life story is a true inspiration for all those who dream big.

Most people know Sally Ride as the first American female astronaut to travel in space. But in her lifetime she was also a nationally ranked tennis player, a physicist who enjoyed reading Shakespeare, a university professor, and the founder of a company that helped inspire girls and young women to pursue careers in science and math. Posthumously, she was a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

From Sally Ride’s youth to her many groundbreaking achievements in space and beyond, Sue Macy’s riveting biography tells the story of not only a pioneering astronaut, but a leader and explorer whose life, as President Barack Obama said, “demonstrates that the sky is no limit for those who dream of reaching for the stars.”

Most people know Sally Ride as the first American female astronaut to travel in space. But in her lifetime she was also a nationally ranked tennis player, a physicist who enjoyed reading Shakespeare, a university professor, and the founder of a company that helped inspire girls and young women to pursue careers in science and math. Posthumously, she was a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

From Sally Ride’s youth to her many groundbreaking achievements in space and beyond, Sue Macy’s riveting biography tells the story of not only a pioneering astronaut, but a leader and explorer whose life, as President Barack Obama said, “demonstrates that the sky is no limit for those who dream of reaching for the stars.”

Excerpt

Sally Ride CHAPTER 1 GROWING UP

ON THE DAY THAT SALLY Kristen ride was born, one of the most popular magazines in the United States featured a short story titled, “Smart Girls Are Helpless.” It was May 26, 1951, less than six years after the end of ?World War II, and the roles of women had undergone several shifts over the previous decade. During the war, the government had depended on women to keep America strong by taking jobs in factories, at shipyards, and in the newly formed all-female branches of the armed forces. Their contributions were crucial to the war effort. When the war was over in 1945, though, most businesses quickly replaced women workers with men. At the same time, many magazines started advising wives to let their husbands take over as breadwinners if they wanted their marriages to last.

“Smart Girls Are Helpless,” which appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, took the same stance as those magazine articles. It focused on an intelligent, independent farmer named Gail who was successful in everything but attracting a man. She preferred to solve problems herself and consistently ignored the advice offered by her handsome neighbor, Charlie. But when Charlie put his farm up for sale, Gail realized that she wanted him in her life. To keep him nearby, she decided to show Charlie that she needed him. She let his prized bull out of its pen and scrambled up a tree with the bull close behind. Charlie heard her cries of ?“Help!” and came to her rescue. His manly pride was restored.

Stories about strong men and helpless women abounded in the world that Sally Ride entered that Saturday in 1951. But from the start, she was as independent and headstrong as the fictional farmer Gail. Her father, Dale Ride, once remarked that he and his wife, Joyce, “haven’t spoken for Sally since she was two, maybe three.”? The Rides’ approach to raising Sally and her younger sister, Bear, was to let them explore the things that interested them. “Dale and I simply forgot to tell them that there were things they couldn’t do,” her mother said in 1983. “But I think if it had occurred to us to tell them, we would have refrained.”

Sally was born in Los Angeles, California, and grew up in a large ranch house in the Encino district of the city. It was an upscale area; another Encino resident in the early 1950s was a promising young comedian named Johnny Carson. He would go on to host NBC’s late-night TV program, The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, for thirty years. Sally’s father was a professor of political science at Santa Monica Community College. Her mother was a stay-at-home mom during Sally’s childhood. Later she taught English to foreign students and spearheaded a group that helped female prison inmates and their families. Both of Sally’s parents also were elders in the Presbyterian Church. As such, they were trained leaders who were deeply involved in the welfare and religious life of their church community.

Sally’s father was born in Colorado, and her mother in Minnesota. Her mother was the grandchild of immigrants. Three of Joyce’s grandparents came from Norway, and the other came from Russia. Sally’s father’s side of the family immigrated from England, with some of his ancestors arriving in colonial times, a century before the Revolutionary War. Sally’s grandfather on her mother’s side, Andy Anderson, owned a movie theater in Minnesota before bringing his family to California and starting a successful chain of movie theaters and bowling alleys. Her other grandfather, Thomas V. Ride, worked in banking, first as a bookkeeper and then as a loan adviser.

By the time she was five years old, Sally had already learned to read, thanks in part to her love of sports. She would regularly race her father for first dibs at their newspaper’s sports section, and when she got it, she would commit the day’s statistics to memory. But she didn’t only read about sports. She also played them. “When kids played baseball or football in the streets, Sally was always the best,” said her sister. “When they chose up sides, Sally was always the first to be chosen. She was the only girl who was acceptable to the boys.” Perhaps it’s not surprising that one of Sally’s early career goals was to play baseball for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Besides the newspaper, Sally read lots of books. Her favorites included the Nancy Drew series, featuring the teenaged amateur sleuth who solved mysteries with the help of her friends. She was also a fan of Ian Fleming’s James Bond, the dashing British Secret Service agent who first appeared in 1953, and she read some science fiction. Like many other middle-class kids in the 1950s and 1960s, she gave in to her parents’ wishes and took piano lessons, but she wasn’t happy about it. As an adult, Sally absolutely refused to play the instrument.

When Sally was nine years old, her father took a year off from his teaching career. The Rides spent this sabbatical year traveling through Europe, with Sally’s mom tutoring her daughters all along the way. It was the first of several turning points in Sally’s life. She returned home with a greater sense of the world and her place in it. Thanks to her adventures and her mother’s teaching skills, she also was half a grade ahead of her classmates.

Back in Encino, Dale Ride set out to steer his older daughter toward a sport that might have fewer violent collisions than the ones she was playing with the neighborhood boys. He suggested tennis, and Sally embraced it with passion. In fact, although her father enjoyed the sport himself, he quickly realized that he was no match for her. He quit playing competitive tennis soon after Sally started.

As an individual sport, tennis requires a combination of athleticism and intelligence. Tennis players need power to hit good shots and stamina to keep going through a long match, but they also need to think fast and anticipate where their opponents will hit the ball. Sally definitely had the physical ability to play the sport. To help develop her mental game, Dale sent his preteen daughter to Alice Marble, one of the most celebrated tennis teachers in California.

During her own tennis career, Alice Marble had risen to the number one ranking in the world. She won the US national women’s singles title four times from 1936 to 1940, and the Wimbledon singles title once, in 1939. Marble excelled in doubles as well as singles. She won the US national women’s doubles title four times, the Wimbledon women’s doubles title twice, the US mixed doubles title four times, and the Wimbledon mixed doubles title three times.

Like Sally, Alice had made a name for herself slamming home runs in neighborhood baseball games prior to taking up tennis. In her case, it was her brother who first handed her a tennis racket. “He said, ‘Go out and play,’?” she once recalled. “I think he wanted me to stop playing baseball with the boys.” Alice brought the same strength she showcased in baseball to the tennis court, hitting a cannonball serve that sizzled across the net. Julius Heldman, a former junior champion himself, once wrote that Alice’s tennis game “was the product of her tomboy days of baseball.” He added, “She played without restraint, running wide-legged, stretching full out for the wide balls, and walloping serves and overheads.”

Although Alice had stood up against the best tennis players of her era, she almost met her match in Sally Ride. “She had talent, a lot of athletic ability,” Alice told the Los Angeles Times in 1983. “But she seemed so frustrated with it. She would hit me with the tennis ball. I had to duck like crazy. It wasn’t that she mis-hit the ball. She had perfect aim.”

California was a hotbed of tennis activity for girls and boys in the 1960s, with a circuit of tournaments for gifted players. One of the products of that system was the legendary champion Billie Jean King, who was also a student of Alice Marble (and yet another former passionate baseball player). Despite her behavior at her tennis lessons, Sally embraced the chance to play in weekend tournaments, especially since that meant missing church. Whatever her motivation, she earned a national ranking by the time she was a teenager.

Sally’s tennis success opened doors to new opportunities that would shape her life. Chief among them was the offer of a partial scholarship to the prestigious Westlake School for Girls, a private school in the hills above Los Angeles. Westlake’s graduates included the former child movie star Shirley Temple, who would go on to become the US ambassador to both Ghana and Czechoslovakia, and future Oscar-nominated and Emmy Award–winning actress Candice Bergen.

When Sally entered Westlake in her sophomore year of high school, she met Susan Okie, a classmate who would grow up to be both a reporter and a medical doctor. In 1983 Okie wrote a series of articles about Sally for the Washington Post, starting with her memories from their Westlake days. “Sally was a fleet-footed fourteen-year-old with keen blue eyes, a self-confident grin, and long, straight hair that perpetually flopped forward over her face,” she wrote. “We were academic rivals, both on scholarships, and carpooled together. . . . We felt out of place along the actors’ daughters and Bel Air belles. Our friendship was instantaneous.”

Sally played on Westlake’s tennis team each of her three years at the school. She served as captain her senior year, leading a team that swept every division of the local interscholastic tournament without losing a set. Westlake’s headmaster in the late 1960s, Norman Reynolds, remembered Sally as being cool and self-confident. He also recalled an up-close-and-personal lesson on how competitive she could be. The headmaster had coaxed Dale Ride onto the tennis court for a friendly doubles match with Sally and another young woman. Though admittedly not a great player, Reynolds managed to poach a shot at the net and hit the ball past Sally for a point. Sally’s response was one that Alice Marble could have predicted. She slammed the next three shots right between the headmaster’s eyes at one hundred miles per hour.

Despite the sting, Reynolds admired Sally’s competitive spirit. He noted that Westlake aimed to teach students “how to handle that competitiveness, how to keep it in perspective.” And indeed, playing tennis at the school did help Sally develop discipline and leadership skills, as well as athletic ability. But Westlake offered excellent academic opportunities too, and Sally embraced them. There was one teacher in particular who inspired her and had a direct influence on the woman she would become.

ON THE DAY THAT SALLY Kristen ride was born, one of the most popular magazines in the United States featured a short story titled, “Smart Girls Are Helpless.” It was May 26, 1951, less than six years after the end of ?World War II, and the roles of women had undergone several shifts over the previous decade. During the war, the government had depended on women to keep America strong by taking jobs in factories, at shipyards, and in the newly formed all-female branches of the armed forces. Their contributions were crucial to the war effort. When the war was over in 1945, though, most businesses quickly replaced women workers with men. At the same time, many magazines started advising wives to let their husbands take over as breadwinners if they wanted their marriages to last.

“Smart Girls Are Helpless,” which appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, took the same stance as those magazine articles. It focused on an intelligent, independent farmer named Gail who was successful in everything but attracting a man. She preferred to solve problems herself and consistently ignored the advice offered by her handsome neighbor, Charlie. But when Charlie put his farm up for sale, Gail realized that she wanted him in her life. To keep him nearby, she decided to show Charlie that she needed him. She let his prized bull out of its pen and scrambled up a tree with the bull close behind. Charlie heard her cries of ?“Help!” and came to her rescue. His manly pride was restored.

Stories about strong men and helpless women abounded in the world that Sally Ride entered that Saturday in 1951. But from the start, she was as independent and headstrong as the fictional farmer Gail. Her father, Dale Ride, once remarked that he and his wife, Joyce, “haven’t spoken for Sally since she was two, maybe three.”? The Rides’ approach to raising Sally and her younger sister, Bear, was to let them explore the things that interested them. “Dale and I simply forgot to tell them that there were things they couldn’t do,” her mother said in 1983. “But I think if it had occurred to us to tell them, we would have refrained.”

Sally was born in Los Angeles, California, and grew up in a large ranch house in the Encino district of the city. It was an upscale area; another Encino resident in the early 1950s was a promising young comedian named Johnny Carson. He would go on to host NBC’s late-night TV program, The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, for thirty years. Sally’s father was a professor of political science at Santa Monica Community College. Her mother was a stay-at-home mom during Sally’s childhood. Later she taught English to foreign students and spearheaded a group that helped female prison inmates and their families. Both of Sally’s parents also were elders in the Presbyterian Church. As such, they were trained leaders who were deeply involved in the welfare and religious life of their church community.

Sally’s father was born in Colorado, and her mother in Minnesota. Her mother was the grandchild of immigrants. Three of Joyce’s grandparents came from Norway, and the other came from Russia. Sally’s father’s side of the family immigrated from England, with some of his ancestors arriving in colonial times, a century before the Revolutionary War. Sally’s grandfather on her mother’s side, Andy Anderson, owned a movie theater in Minnesota before bringing his family to California and starting a successful chain of movie theaters and bowling alleys. Her other grandfather, Thomas V. Ride, worked in banking, first as a bookkeeper and then as a loan adviser.

By the time she was five years old, Sally had already learned to read, thanks in part to her love of sports. She would regularly race her father for first dibs at their newspaper’s sports section, and when she got it, she would commit the day’s statistics to memory. But she didn’t only read about sports. She also played them. “When kids played baseball or football in the streets, Sally was always the best,” said her sister. “When they chose up sides, Sally was always the first to be chosen. She was the only girl who was acceptable to the boys.” Perhaps it’s not surprising that one of Sally’s early career goals was to play baseball for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Besides the newspaper, Sally read lots of books. Her favorites included the Nancy Drew series, featuring the teenaged amateur sleuth who solved mysteries with the help of her friends. She was also a fan of Ian Fleming’s James Bond, the dashing British Secret Service agent who first appeared in 1953, and she read some science fiction. Like many other middle-class kids in the 1950s and 1960s, she gave in to her parents’ wishes and took piano lessons, but she wasn’t happy about it. As an adult, Sally absolutely refused to play the instrument.

When Sally was nine years old, her father took a year off from his teaching career. The Rides spent this sabbatical year traveling through Europe, with Sally’s mom tutoring her daughters all along the way. It was the first of several turning points in Sally’s life. She returned home with a greater sense of the world and her place in it. Thanks to her adventures and her mother’s teaching skills, she also was half a grade ahead of her classmates.

Back in Encino, Dale Ride set out to steer his older daughter toward a sport that might have fewer violent collisions than the ones she was playing with the neighborhood boys. He suggested tennis, and Sally embraced it with passion. In fact, although her father enjoyed the sport himself, he quickly realized that he was no match for her. He quit playing competitive tennis soon after Sally started.

As an individual sport, tennis requires a combination of athleticism and intelligence. Tennis players need power to hit good shots and stamina to keep going through a long match, but they also need to think fast and anticipate where their opponents will hit the ball. Sally definitely had the physical ability to play the sport. To help develop her mental game, Dale sent his preteen daughter to Alice Marble, one of the most celebrated tennis teachers in California.

During her own tennis career, Alice Marble had risen to the number one ranking in the world. She won the US national women’s singles title four times from 1936 to 1940, and the Wimbledon singles title once, in 1939. Marble excelled in doubles as well as singles. She won the US national women’s doubles title four times, the Wimbledon women’s doubles title twice, the US mixed doubles title four times, and the Wimbledon mixed doubles title three times.

Like Sally, Alice had made a name for herself slamming home runs in neighborhood baseball games prior to taking up tennis. In her case, it was her brother who first handed her a tennis racket. “He said, ‘Go out and play,’?” she once recalled. “I think he wanted me to stop playing baseball with the boys.” Alice brought the same strength she showcased in baseball to the tennis court, hitting a cannonball serve that sizzled across the net. Julius Heldman, a former junior champion himself, once wrote that Alice’s tennis game “was the product of her tomboy days of baseball.” He added, “She played without restraint, running wide-legged, stretching full out for the wide balls, and walloping serves and overheads.”

Although Alice had stood up against the best tennis players of her era, she almost met her match in Sally Ride. “She had talent, a lot of athletic ability,” Alice told the Los Angeles Times in 1983. “But she seemed so frustrated with it. She would hit me with the tennis ball. I had to duck like crazy. It wasn’t that she mis-hit the ball. She had perfect aim.”

California was a hotbed of tennis activity for girls and boys in the 1960s, with a circuit of tournaments for gifted players. One of the products of that system was the legendary champion Billie Jean King, who was also a student of Alice Marble (and yet another former passionate baseball player). Despite her behavior at her tennis lessons, Sally embraced the chance to play in weekend tournaments, especially since that meant missing church. Whatever her motivation, she earned a national ranking by the time she was a teenager.

Sally’s tennis success opened doors to new opportunities that would shape her life. Chief among them was the offer of a partial scholarship to the prestigious Westlake School for Girls, a private school in the hills above Los Angeles. Westlake’s graduates included the former child movie star Shirley Temple, who would go on to become the US ambassador to both Ghana and Czechoslovakia, and future Oscar-nominated and Emmy Award–winning actress Candice Bergen.

When Sally entered Westlake in her sophomore year of high school, she met Susan Okie, a classmate who would grow up to be both a reporter and a medical doctor. In 1983 Okie wrote a series of articles about Sally for the Washington Post, starting with her memories from their Westlake days. “Sally was a fleet-footed fourteen-year-old with keen blue eyes, a self-confident grin, and long, straight hair that perpetually flopped forward over her face,” she wrote. “We were academic rivals, both on scholarships, and carpooled together. . . . We felt out of place along the actors’ daughters and Bel Air belles. Our friendship was instantaneous.”

Sally played on Westlake’s tennis team each of her three years at the school. She served as captain her senior year, leading a team that swept every division of the local interscholastic tournament without losing a set. Westlake’s headmaster in the late 1960s, Norman Reynolds, remembered Sally as being cool and self-confident. He also recalled an up-close-and-personal lesson on how competitive she could be. The headmaster had coaxed Dale Ride onto the tennis court for a friendly doubles match with Sally and another young woman. Though admittedly not a great player, Reynolds managed to poach a shot at the net and hit the ball past Sally for a point. Sally’s response was one that Alice Marble could have predicted. She slammed the next three shots right between the headmaster’s eyes at one hundred miles per hour.

Despite the sting, Reynolds admired Sally’s competitive spirit. He noted that Westlake aimed to teach students “how to handle that competitiveness, how to keep it in perspective.” And indeed, playing tennis at the school did help Sally develop discipline and leadership skills, as well as athletic ability. But Westlake offered excellent academic opportunities too, and Sally embraced them. There was one teacher in particular who inspired her and had a direct influence on the woman she would become.

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (September 9, 2014)

- Length: 160 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442488540

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 1170L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Awards and Honors

- CBC/NSTA Outstanding Science Trade Book

- Amelia Bloomer List

- MSTA Reading Circle List

Resources and Downloads

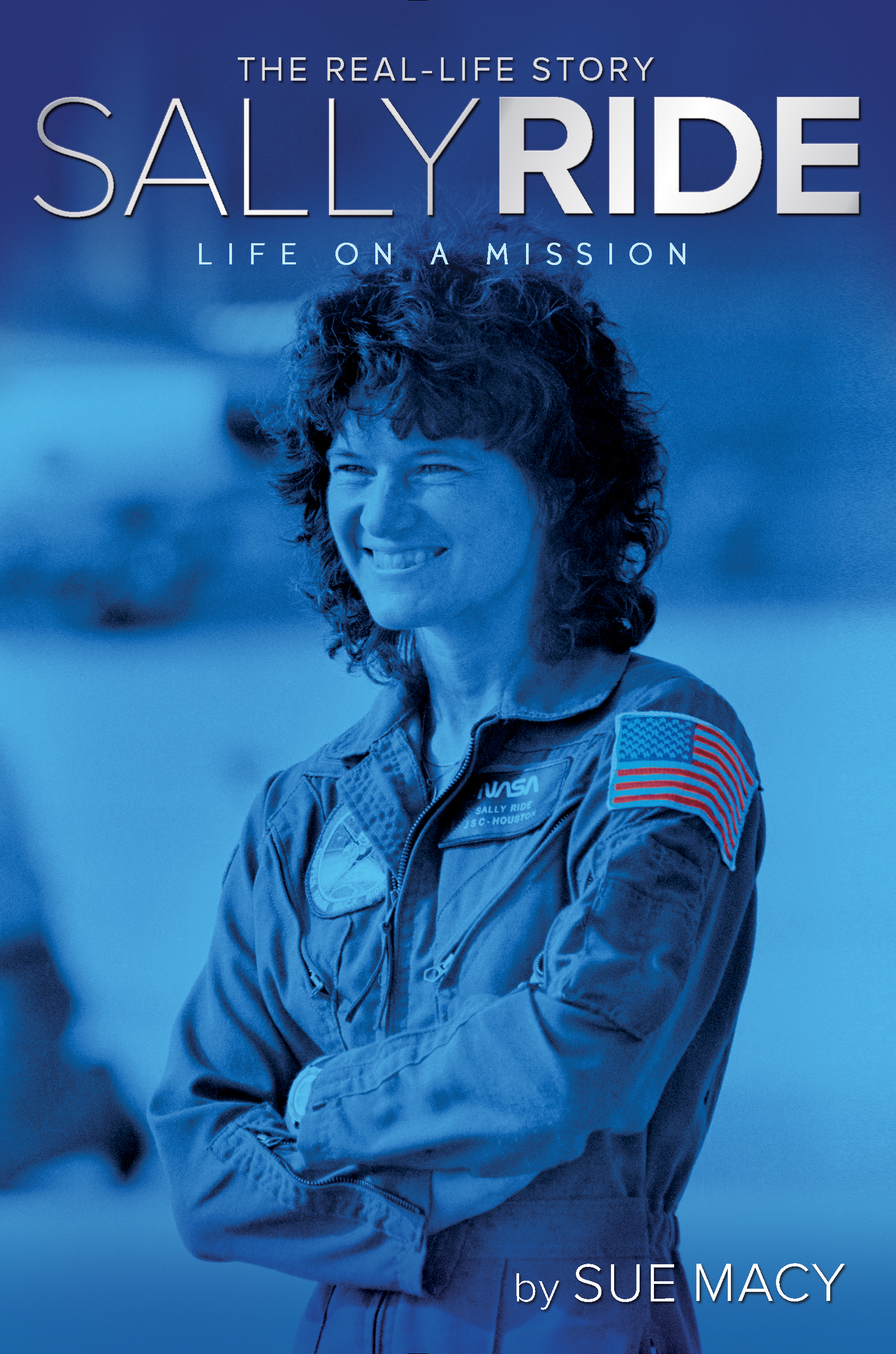

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Sally Ride Hardcover 9781442488540(3.3 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Sue Macy Duane Stork Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit