Dancing Home

By Alma Flor Ada and Gabriel M. Zubizarreta

LIST PRICE $7.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

In this timely tale of immigration, two cousins learn the importance of family and friendship.

A year of discoveries culminates in a performance full of surprises, as two girls find their own way to belong.

Mexico may be her parents’ home, but it’s certainly not Margie’s. She has finally convinced the other kids at school she is one-hundred percent American—just like them. But when her Mexican cousin Lupe visits, the image she’s created for herself crumbles.

Things aren’t easy for Lupe, either. Mexico hadn’t felt like home since her father went North to find work. Lupe’s hope of seeing him in the United States comforts her some, but learning a new language in a new school is tough. Lupe, as much as Margie, is in need of a friend.

Little by little, the girls’ individual steps find the rhythm of one shared dance, and they learn what “home” really means. In the tradition of My Name is Maria Isabel—and simultaneously published in English and in Spanish—Alma Flor Ada and her son Gabriel M. Zubizarreta offer an honest story of family, friendship, and the classic immigrant experience: becoming part of something new, while straying true to who you are.

A year of discoveries culminates in a performance full of surprises, as two girls find their own way to belong.

Mexico may be her parents’ home, but it’s certainly not Margie’s. She has finally convinced the other kids at school she is one-hundred percent American—just like them. But when her Mexican cousin Lupe visits, the image she’s created for herself crumbles.

Things aren’t easy for Lupe, either. Mexico hadn’t felt like home since her father went North to find work. Lupe’s hope of seeing him in the United States comforts her some, but learning a new language in a new school is tough. Lupe, as much as Margie, is in need of a friend.

Little by little, the girls’ individual steps find the rhythm of one shared dance, and they learn what “home” really means. In the tradition of My Name is Maria Isabel—and simultaneously published in English and in Spanish—Alma Flor Ada and her son Gabriel M. Zubizarreta offer an honest story of family, friendship, and the classic immigrant experience: becoming part of something new, while straying true to who you are.

Excerpt

The Map

Margie felt nervous having to wait outside the principal’s office. She kept her eyes fixed on the huge map that covered the entire wall. Mrs. Donaldson seemed to be a pleasant woman, but Margie had never had to address the principal all by herself before.

The map’s colors were vivid and bold, showing Canada, the United States, and part of Mexico. Alaska and the rest of the United States were a strong green; Canada was a bright yellow. The remainder of the map, however, showed only a small part of Mexico in a drab sandlike color Margie could not name.

For Margie, maps were an invitation to wonder, a promise that someday she would visit faraway places all over the world.

Looking at this one, Margie could imagine herself admiring the giant glaciers in Alaska, standing in awe in front of the Grand Canyon, gazing at the endless plains of the Midwest, trying to find her way in the midst of bustling New York City, or peering at the rocky coasts of Maine . . . but when her eyes began to wander south of the border, she averted her gaze. That is not a place I want to visit, she thought, remembering so many conversations between her parents and their neighbors, tales of families not having enough money to live a decent life, of sick people lacking medical care, and of people losing their land and homes. As she pushed those troubling thoughts aside, Margie’s heart once again swelled with pride, knowing she had been born north of that border, in the United States, an American.

Margie looked over at the girl waiting in the other chair outside the principal’s office. Her cousin Lupe was not as lucky as Margie, who had been born in the United States. Lupe had just arrived from Mexico and looked completely out of place in that silly frilly dress she had insisted on wearing. “My mother made it especially for me,” she had pleaded, and Margie’s mother had allowed her to wear it. That dress was much too fancy for school. It was so embarrassing for Margie to be seen with a cousin who was dressed like a doll!

Margie knew her classmates would tease Lupe about her organza dress and her long braids. Would all that teasing spill over to Margie? Were they going to start mocking her, squealing “Maargereeeeeta, Maargereeeeeta” and asking her when had she crossed over from Mexico? She had hated it so much when they used to tease her like that!

It had been such a struggle for Margie to get her classmates to stop thinking of her as Mexican. She was very proud of having been born in Texas. She was as American as anyone else. Now Margie feared that because Lupe was tagging along in that dumb dress, everyone would start back up with the teasing she had hated so much. She could just hear her classmates asking her why she didn’t bring burritos for lunch, or looking at her and laughing as they said, “No way, José!”

Margie was still wishing she could have convinced Lupe to dress normally when the principal appeared, walking briskly and motioning for the girls to follow her into her office.

“Good morning, Margarita. What can I do for you?” Mrs. Donaldson’s voice was all business. Everything about her seemed to say, I do not have a minute to spare.

“Good morning, Mrs. Donaldson. This is my cousin Lupe. She just got here from Mexico. My mother said—”

Mrs. Donaldson, who had begun to shuffle the papers on her desktop, interrupted Margie: “Your mother registered her yesterday, Margarita. Just take her with you to your class.”

“To my class?” There was surprise and urgency in Margie’s voice. “But she just got here. She is from Mexico. She doesn’t know how to speak.”

Mrs. Donaldson stared at Margie. “You mean she doesn’t know how to speak English, right? I imagine she can speak Spanish.” Then, turning to Lupe, she slowly said, “Bien—ve—ni—da to Fair Oaks, Lupe. Bonito vestido.”

Lupe managed a shy smile, but she kept looking down at her feet and answered in the smallest voice, “Muchas gracias—”

Margie cut through Lupe’s words. “Well, yes, she speaks Spanish. But in my class we only speak English. She is not going to fit in there, Mrs. Donaldson.” She was shocked at her audacity in arguing with the principal, but there was no way she was going to show up in class with her Mexican cousin tagging along. Why had Mrs. Donaldson complimented Lupe’s stupid party dress? How could adults be so dishonest? Margie wondered.

Mrs. Donaldson said firmly, “The fifth-grade bilingual class is overbooked. There is no way I can put one more desk in there. Judging by her grades in Mexico, Lupe is a very good student, and since you can help her, both here and at home, we all expect that she will do well in your class.” And with a voice that left no room for a reply, she added, “I thought you would be happy about this. She is your cousin, Margarita!”

Mrs. Donaldson looked so stern that Margie decided not to say anything else. She got up and left, signaling Lupe to follow her. But as she was leaving the office, she looked back at the huge map of the United States. This was a great country, and she was very glad that she had been born here and spoke English as well as any of her friends.

Lupe followed Margie down the hall. She had not understood the conversation in the principal’s office. It was clear to Lupe that her cousin was upset, but Lupe did not know why. As they made their way to the classroom, everything Lupe saw awakened her curiosity. It was all so different from Mexico! She had never been to a school with so many things hanging on the walls. And she still could not believe that the students didn’t wear uniforms. She had been very surprised when her aunt told her. When Lupe arrived in California, Tía Consuelo had bought her some new clothes to wear to school. But for this first day Lupe had wanted to wear the pink organza dress her mother had made. Margie did not seem to like it, but Lupe felt it was important to give a good first impression.

When Margie opened the door, Lupe’s surprise grew. They were obviously in a classroom, but instead of the neat rows of desks that she was used to, the students were sitting in small clusters of two or four desks placed around the room. And there were all sorts of different things in the classroom—posters on the walls, mobiles hanging from the ceiling, many different kinds of books on the bookshelves. There was even a fish tank! With binders and backpacks scattered all over, it looked very chaotic, more like a bus station than a classroom.

Stunned, Lupe hesitated in the doorway, afraid to walk in. Glancing at everything from the corners of her eyes, she remembered the neat and orderly classroom of her old school in Mexico. Suddenly she became aware that everyone in the room was looking at her. She dropped her gaze and stared down at the floor in front of her feet.

Meanwhile, Margie went directly to the teacher’s desk.

“Miss Jones, this is my cousin Lupe González. Mrs. Donaldson told me to bring her here. But there must be some mistake. She should be in a bilingual class, right?”

The teacher did not answer Margie’s question but turned to address Lupe. Margie looked back at Lupe, who had not moved, trying to signal her to come in. Finally, Margie walked back to the door and took hold of her cousin’s arm. Lupe jumped a little when Margie grabbed her, and the class was instantly filled with laughter. Lupe raised her eyes and saw that her cousin’s face had turned crimson.

Obviously upset, Margie led Lupe over to Miss Jones’s desk.

“Buenos días, Lupe. ¿Cómo estás usted?” Miss Jones said slowly, pronouncing each syllable of the formal greeting.

Surprised at being addressed so formally, Lupe did not know how to answer the teacher’s halting Spanish. But she knew how to show respect, so she looked down. More laughter spread around the room.

“Margie, have your cousin sit next to you, in the back of the class, so that you can translate what I say. That is all the Spanish I know.”

“But Miss Jones . . .” The urgency in Margie’s voice was greater than ever. “I don’t know much Spanish myself. I won’t be able to translate everything you say. Besides, I sit up front, next to Liz.”

“I have moved you next to the empty seat in the back. That way you can translate while I speak and you won’t disturb the rest of the class. Now go sit down, class should have started already. And please tell your cousin that even if she is feeling shy, she needs to look at me when I am talking to her.”

Margie sulked toward her new seat, while Lupe continued to stand in front of the teacher’s desk. When the laughter started up again, Margie turned and grabbed Lupe, pulling her toward the back of the class. Lupe followed silently. When she dared to look up and smile, the laughter started again, until Miss Jones demanded silence.

While Miss Jones talked on and on about the Pilgrims, Margie searched for the words in Spanish to translate what the teacher was saying. But there was no way she could even begin to convey the half of it, and so she remained silent instead. Lupe looked expectantly at the teacher for a moment, but then she busied herself turning the pages of the history book and looking at the illustrations.

Margie felt deeply hurt. She had always liked sitting up front. And Liz was her best friend. Now she had to sit at the other end of the room, while Betty sat next to Liz. Margie could see them chatting and smiling as if they were already best friends.

Margie had joined in the family excitement when her mother announced that her cousin Lupe was coming to stay with them. Margie had no brothers or sisters, and since none of her school friends lived close by, she thought it might be fun to have someone to hang out with at home. Besides, Lupe could help with the chores—washing and drying dishes and cleaning and straightening the kitchen after dinner would be less boring if the two of them were working together. But above all Margie had hoped that once Lupe was here, it would be easier to convince her mother to let her visit Liz and go out to the mall.

Margie had not thought at all about how having Lupe here might affect her life at school. She had imagined parting ways at the school door, Lupe going to the bilingual classroom and Margie going to her own classroom with her friends.

“Margie! Are you listening to me?” Miss Jones sounded angry. Everyone was staring at Margie, who again felt her face getting warm. “When are you going to start explaining to your cousin what I have been saying?”

“But I told you, Miss Jones. I don’t know that much Spanish. I was born in Texas.” Margie’s voice could hardly be heard, but what could be heard loud and clear was the laughter coming from John and Peter, the two boys sitting on her right.

“Enough!” Miss Jones gave John and Peter one of her silencing looks. “Take out your math workbooks.”

Margie felt confused. How could things change so quickly? She had felt so comfortable in this class, and now everything seemed out of control. She looked down at her math workbook, although the numbers looked so blurry that she could hardly read them.

During the exchange between the teacher and her cousin, Lupe never raised her head. Even though she did not understand the words, she knew they had to do with her, and she felt so embarrassed that she buried her face in the history book. What she really wanted was to crawl under the desk, or better yet, to run all the way back to Mexico.

Miss Jones walked to the back of the room and placed an open workbook on Lupe’s desk. Lupe looked down at the numbers on the page and smiled. Finally, here was something she knew how to do! She took out her pencil and began to add, subtract, multiply, and divide, while Margie worked, much more slowly, on a similar page.

When she finished the last equation, Lupe turned the page. But on the next page there were no numbers, only words. She looked at Margie, but Margie was not even halfway down the first page.

Lupe felt lost again and her eyes became moist with tears.

When Miss Jones came to her desk to look at her work, Lupe turned to the page she had completed.

“Excellent!” the teacher exclaimed, pleased. “¡Excelente!” She held the page up for everyone to see. Then she added, “Margie, would you please translate the word problems on the next page for her?”

But Margie looked up from the workbook and shook her head. “I can’t, Miss Jones. Really, I can’t.”

Miss Jones found Lupe another page with numbers and returned to the front of the class.

While the teacher walked back to her desk, Lupe was looking at Margie’s work. She pointed to one of the solutions Margie had written and said to her, “No es así.” Lupe heard a small laugh from the boys and a “No excelente, Maaargaaareeetaaa.” Again she looked down and blushed, wishing she had not said anything at all.

At lunchtime Margie and Lupe were at the end of the line. Lupe saw Margie look for a seat near the girl with the curly hair, but when they finally got their food, all the other seats were filled. Lupe and Margie were forced to sit at the opposite end of the table.

A few times during lunch Lupe tried to say something, but Margie silenced her. Lupe ate quietly. Margie left most of her food on the tray.

© 2011 Alma Flor Ada

Reading Group Guide

A Reading Group Guide for:

Dancing Home (Nacer Bailando)

By Alma Flor Ada and Gabriel M. Zubizarreta

The author of this book proposes that effective reading is a dialogue, albeit silent, between reader and text, a process she has described as creative reading. Reading transcends the author’s words, being heightened by the reader’s previous knowledge. The reader’s previous experiences inspire feelings in response to the text and critical reflections on what the text proposes. Above all, through this dialogue with the text, readers can discover new possibilities for action in their lives, strength to act more courageously, with greater kindness, compassion, empathy; and knowledge to act more wisely, with greater understanding or determination.

About the Book

Mexico may be her parents’ home, but it’s certainly not Margie’s. She has finally convinced the other kids at school she is one hundred percent American—just like them. But when her Mexican cousin Lupe visits, the image she’s created for herself crumbles.

Things aren’t easy for Lupe, either. Mexico hadn’t felt like home since her father went North to find work. Lupe’s hope of seeing him in the United States comforts her some, but learning a new language in a new school is tough. Lupe, as much as Margie, is in need of a friend.

Little by little, the girls’ individual steps find the rhythm of one shared dance, and they learn what “home” really means.

Discussion Questions

1. As Margie visits the principal’s office in preparation for Lupe’s enrollment in her school, she notices a map of North America with vivid and bold colors for the United States and Canada, yet the part of Mexico included is displayed in a drab, sandlike color. In what ways does the imagery of the map capture Margie’s feelings for her parents’ birthplace? What is it about her understanding of Mexico that makes her feel this way?

2. Consider the dress that Lupe wears on the first day of school. What does it symbolize for Lupe? Why does Margie have such a different reaction to it? Why are Margie's feelings so strong? How do you think you would have felt in Margie's place?

3. Though she is initially hesitant, why does Lupe ultimately choose to go to California with her aunt Consuelo? Lupe “feels like a stranger in her own home”—how is that so? What changes in her home life have promoted this shift?

4. Margie really prides herself with being born north of the border as an American. In your opinion, what leads Margie to have such strong feelings toward her citizenship? How do you feel about her attitude regarding her place as a US citizen? Do you think the place of birth is the only qualification to be a good citizen? Why or why not?

5. After working hard to convince her mom that rather than long, straight hair, a head full of brown curls is the ideal image of a true American girl, Margie feels jealous of her mother’s intimacy with Lupe as she assists her niece with brushing and braiding her hair. In your opinion, do you think Margie has a reason to be jealous? Why or why not?

6. Explain the significance of the title, Dancing Home. What events and relationships portrayed in the book are expressed by this title?

7. While discussing her unwillingness to speak Spanish in the classroom to assist her cousin Lupe, Margie tells her mother, “But we live in America, Mom. This is an English-speaking country. Live in America, speak American. That’s what they all say.” Have you heard similar statements before? Do you speak a language other than English? Does anyone in your family? What are your feelings about being bilingual?

8. How does Margie's interpretation of her peers' attitudes toward Mexico impact her relationship with her parents, and with Lupe?

9. Why does Margie feel so disappointed that with Lupe’s arrival, the way Margie’s family has celebrated Christmas in the past is put aside to celebrate a more traditional Mexican Christmas? Do you think her parents are right to do so? What do Margie and Lupe gain from this holiday experience?

10. Consider the variety of settings for Dancing Home and name the three places you believe to be most important to the story. Using textual evidence from the book, explain why you find them to be significant to the story.

11. For what reasons do you think Margie feels connected to her friend Camille? In what ways are the two of them similar? How would you characterize the relationship between the two of them, and how does it change over the course of the novel?

12. Describe Lupe. How does she change throughout the story? Have you ever shared any of her feelings? Explain.

13. In what ways does the visit by her uncle Francisco help make Margie more understanding of the struggles faced by Lupe? Francisco failed Lupe in many ways, yet he is finally able to give her a powerful gift. Do you believe Lupe will benefit from her father's message? Explain your answer.

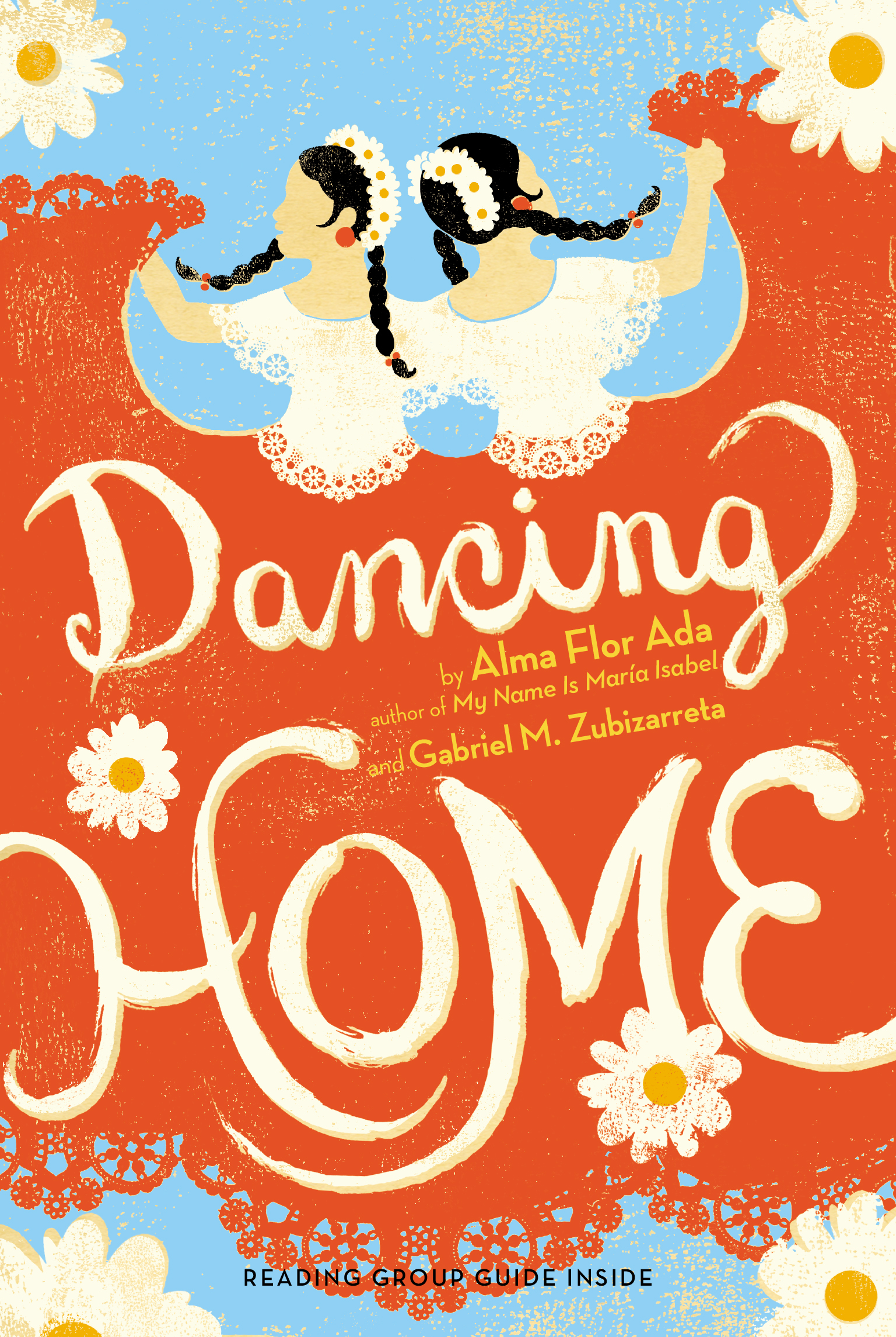

14. Consider the novel’s cover art. In what ways is the image represented symbolic for the events that transpire throughout the course of the book?

15. In your opinion, in what ways does Margie’s shift in understanding of who she is change throughout the course of the novel? In what ways does Camille help Margie better understand and appreciate her heritage?

16. Do you feel that reading this book has given you new insight about what immigrant students may experience? About any other issue? Please explain your answer.

17. Using the phrase, “This is a story about . . .” supply five words to describe Dancing Home. Explain your choices.

Activities and Research

1. In the course of the novel, readers learn that Margie’s grandfather was part of the Bracero Program. Using the library and the internet, research to learn more about this government program, being sure to consider how many workers participated, where these farm workers provided assistance, and what the benefits and challenges were.

2. In Dancing Home, Margie struggles when her American Christmas is modified so that her family can celebrate a more traditional Mexican holiday. Using the library and the internet, research what the major similarities and differences are between Christmas in Mexico and Christmas in the United States.

3. Make thematic connections. Consider the themes of Dancing Home: examples include (but are not limited to) family, friendship, sacrifice, and courage. Select a theme and find examples from the book that help support this theme. Create a sample Life Lesson Chart using the model at: http://www.readwritethink.org/lesson_images/lesson826/chart.pdf.

4. Dancing plays an important role throughout the novel and in particular, in Margie’s relationship with her cousin Lupe. Find out more about folklorico dances, being sure to focus on the importance of music, costumes, and their purpose for celebrations like Cinco de Mayo.

5. Language is also a very important theme in Dancing Home. Find out about the language history in the United States. Which languages were spoken in this land before English? What are the personal benefits of speaking more than one language? What are the benefits for society when languages are maintained?

6. In Dancing Home, part of Margie's and Lupe’s stories focus on their connection and relationship with each other and their need to come together as a family. Consider your most special relationships. What makes these individuals so important? Compose a personal journal entry where you share your thoughts, and be sure to answer the following questions:

• Who are the individuals who mean the most to you?

• Why are these particular relationships so special?

• What’s the greatest sacrifice you’ve made for the people you love?

• In what ways have the changes you’ve experienced in your life affected those to whom you are closest?

Share your writing with the group.

Guide written by Rose Brock, a teacher, school librarian, and doctoral candidate at Texas Woman’s University, specializing in children’s and young adult literature.

This guide has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

Dancing Home (Nacer Bailando)

By Alma Flor Ada and Gabriel M. Zubizarreta

The author of this book proposes that effective reading is a dialogue, albeit silent, between reader and text, a process she has described as creative reading. Reading transcends the author’s words, being heightened by the reader’s previous knowledge. The reader’s previous experiences inspire feelings in response to the text and critical reflections on what the text proposes. Above all, through this dialogue with the text, readers can discover new possibilities for action in their lives, strength to act more courageously, with greater kindness, compassion, empathy; and knowledge to act more wisely, with greater understanding or determination.

About the Book

Mexico may be her parents’ home, but it’s certainly not Margie’s. She has finally convinced the other kids at school she is one hundred percent American—just like them. But when her Mexican cousin Lupe visits, the image she’s created for herself crumbles.

Things aren’t easy for Lupe, either. Mexico hadn’t felt like home since her father went North to find work. Lupe’s hope of seeing him in the United States comforts her some, but learning a new language in a new school is tough. Lupe, as much as Margie, is in need of a friend.

Little by little, the girls’ individual steps find the rhythm of one shared dance, and they learn what “home” really means.

Discussion Questions

1. As Margie visits the principal’s office in preparation for Lupe’s enrollment in her school, she notices a map of North America with vivid and bold colors for the United States and Canada, yet the part of Mexico included is displayed in a drab, sandlike color. In what ways does the imagery of the map capture Margie’s feelings for her parents’ birthplace? What is it about her understanding of Mexico that makes her feel this way?

2. Consider the dress that Lupe wears on the first day of school. What does it symbolize for Lupe? Why does Margie have such a different reaction to it? Why are Margie's feelings so strong? How do you think you would have felt in Margie's place?

3. Though she is initially hesitant, why does Lupe ultimately choose to go to California with her aunt Consuelo? Lupe “feels like a stranger in her own home”—how is that so? What changes in her home life have promoted this shift?

4. Margie really prides herself with being born north of the border as an American. In your opinion, what leads Margie to have such strong feelings toward her citizenship? How do you feel about her attitude regarding her place as a US citizen? Do you think the place of birth is the only qualification to be a good citizen? Why or why not?

5. After working hard to convince her mom that rather than long, straight hair, a head full of brown curls is the ideal image of a true American girl, Margie feels jealous of her mother’s intimacy with Lupe as she assists her niece with brushing and braiding her hair. In your opinion, do you think Margie has a reason to be jealous? Why or why not?

6. Explain the significance of the title, Dancing Home. What events and relationships portrayed in the book are expressed by this title?

7. While discussing her unwillingness to speak Spanish in the classroom to assist her cousin Lupe, Margie tells her mother, “But we live in America, Mom. This is an English-speaking country. Live in America, speak American. That’s what they all say.” Have you heard similar statements before? Do you speak a language other than English? Does anyone in your family? What are your feelings about being bilingual?

8. How does Margie's interpretation of her peers' attitudes toward Mexico impact her relationship with her parents, and with Lupe?

9. Why does Margie feel so disappointed that with Lupe’s arrival, the way Margie’s family has celebrated Christmas in the past is put aside to celebrate a more traditional Mexican Christmas? Do you think her parents are right to do so? What do Margie and Lupe gain from this holiday experience?

10. Consider the variety of settings for Dancing Home and name the three places you believe to be most important to the story. Using textual evidence from the book, explain why you find them to be significant to the story.

11. For what reasons do you think Margie feels connected to her friend Camille? In what ways are the two of them similar? How would you characterize the relationship between the two of them, and how does it change over the course of the novel?

12. Describe Lupe. How does she change throughout the story? Have you ever shared any of her feelings? Explain.

13. In what ways does the visit by her uncle Francisco help make Margie more understanding of the struggles faced by Lupe? Francisco failed Lupe in many ways, yet he is finally able to give her a powerful gift. Do you believe Lupe will benefit from her father's message? Explain your answer.

14. Consider the novel’s cover art. In what ways is the image represented symbolic for the events that transpire throughout the course of the book?

15. In your opinion, in what ways does Margie’s shift in understanding of who she is change throughout the course of the novel? In what ways does Camille help Margie better understand and appreciate her heritage?

16. Do you feel that reading this book has given you new insight about what immigrant students may experience? About any other issue? Please explain your answer.

17. Using the phrase, “This is a story about . . .” supply five words to describe Dancing Home. Explain your choices.

Activities and Research

1. In the course of the novel, readers learn that Margie’s grandfather was part of the Bracero Program. Using the library and the internet, research to learn more about this government program, being sure to consider how many workers participated, where these farm workers provided assistance, and what the benefits and challenges were.

2. In Dancing Home, Margie struggles when her American Christmas is modified so that her family can celebrate a more traditional Mexican holiday. Using the library and the internet, research what the major similarities and differences are between Christmas in Mexico and Christmas in the United States.

3. Make thematic connections. Consider the themes of Dancing Home: examples include (but are not limited to) family, friendship, sacrifice, and courage. Select a theme and find examples from the book that help support this theme. Create a sample Life Lesson Chart using the model at: http://www.readwritethink.org/lesson_images/lesson826/chart.pdf.

4. Dancing plays an important role throughout the novel and in particular, in Margie’s relationship with her cousin Lupe. Find out more about folklorico dances, being sure to focus on the importance of music, costumes, and their purpose for celebrations like Cinco de Mayo.

5. Language is also a very important theme in Dancing Home. Find out about the language history in the United States. Which languages were spoken in this land before English? What are the personal benefits of speaking more than one language? What are the benefits for society when languages are maintained?

6. In Dancing Home, part of Margie's and Lupe’s stories focus on their connection and relationship with each other and their need to come together as a family. Consider your most special relationships. What makes these individuals so important? Compose a personal journal entry where you share your thoughts, and be sure to answer the following questions:

• Who are the individuals who mean the most to you?

• Why are these particular relationships so special?

• What’s the greatest sacrifice you’ve made for the people you love?

• In what ways have the changes you’ve experienced in your life affected those to whom you are closest?

Share your writing with the group.

Guide written by Rose Brock, a teacher, school librarian, and doctoral candidate at Texas Woman’s University, specializing in children’s and young adult literature.

This guide has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (February 5, 2013)

- Length: 176 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442481756

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 960L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Awards and Honors

- California Collections

- Georgia Children's Book Award Finalist

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Dancing Home Trade Paperback 9781442481756(2.9 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Alma Flor Ada (0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit