LIST PRICE $15.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Delve into the extraordinary abilities of the twelve-year-old mind in this thrilling start to a middle-grade series that expands the possibilities of power.

No one has any confidence in twelve-year-old Christopher Lane. His teachers discount him as a liar and a thief, and his mom doesn’t have the energy to deal with him. But a mysterious visit from the Ministry of Education indicates that Chris might have some potential after all: He is invited to attend the prestigious Myers Holt Academy.

When Christopher begins at his new school, he is astounded at what he can do. It seems that age twelve is a special time for the human brain, which is capable of remarkable feats—as also evidenced by Chris’s peers Ernest and Mortimer Genver, who, at the direction of their vengeful and manipulative mother, are testing the boundaries of the human mind.

But all this experimentation has consequences, and Chris soon finds himself forced to face them—or his new life will be over before it can begin.

No one has any confidence in twelve-year-old Christopher Lane. His teachers discount him as a liar and a thief, and his mom doesn’t have the energy to deal with him. But a mysterious visit from the Ministry of Education indicates that Chris might have some potential after all: He is invited to attend the prestigious Myers Holt Academy.

When Christopher begins at his new school, he is astounded at what he can do. It seems that age twelve is a special time for the human brain, which is capable of remarkable feats—as also evidenced by Chris’s peers Ernest and Mortimer Genver, who, at the direction of their vengeful and manipulative mother, are testing the boundaries of the human mind.

But all this experimentation has consequences, and Chris soon finds himself forced to face them—or his new life will be over before it can begin.

Excerpt

The Ability • CHAPTER ONE •

Wednesday, October 17

Cecil Humphries, the government minister for education, despised most things, amongst them:

Cyclists.

The seaside.

Being called by his first name.

Weddings.

The color yellow.

Singing.

But at the top of this list was children. He hated them, which was rather unfortunate given that he was in charge of the well-being of every child in Britain. He knew, however, that the public was rather fond of them, for some reason he couldn’t fathom, and so he had reluctantly accepted the position, sure that it would boost his flagging popularity and take him one step closer toward his ultimate goal: to take the job of his old school friend Prime Minister Edward Banks. Unfortunately for him, the public was far more perceptive than he gave them credit for, and kissing a couple of babies’ heads (then wiping his mouth afterward) had resulted only in a series of frustrating headlines, including:

HUMPHRIES LOVES BABIES

(BUT HE COULDN’T EAT A WHOLE ONE)

The more he tried to improve his image, the more it backfired on him, which only intensified his hatred of anybody under the age of eighteen, if that were at all possible.

It was only fitting, therefore, that the person who would ruin his career and leave him a quivering wreck in a padded cell for the rest of his life would be a twelve-year-old boy.

• • •

The beginning of the end for Cecil Humphries began on an uncharacteristically warm, sunny day in Liverpool. It had been four days since he had been photographed by a well-placed paparazzo stealing chocolate from the hospital bedside of a sick child and only two days since he had been pelted with eggs and flour when the photograph appeared on the front page of every newspaper in the country. Even for someone well accustomed to bad press, this had been a particularly awful week.

Humphries looked out of the window of his chauffeured car, saw the smiling children, and sighed.

“Never work with animals or children. Anyone ever tell you that?” he grumbled. James, his assistant, looked up from his notes, nodded obediently, and said nothing, as he had learned to do.

“Different school, same brats,” he continued as the car pulled up outside the school entrance. “It’s like reliving the same nightmare every single time: a disgusting mass of grubby hands, crying, and runny noses.”

He took out a comb from his jacket pocket and ran it through what remained of his hair.

“You know which ones wind me up the most, though?”

“No, sir,” said James.

“The cute ones. Can’t stand them, with their big eyes and irritating questions.” He shuddered at the thought. “Do try to keep those ones away from me today, would you? I’m really not in the mood.” Humphries adjusted his dark blue tie and leaned over to open the car door.

“What’s the name of this cesspit?” he asked as he pulled back the door handle.

“Perrington School, sir. I briefed you about it earlier.”

“Yes, well, I wasn’t listening. Tell me now,” said Humphries, irritated.

“You’re presenting them with an award for excellence. Also, we’ve invited the press to follow you around while you tour the school and talk to the children. It’ll be a good opportunity for the public to see you in a more, um, positive light. And we’ve been promised a very warm welcome,” explained James.

Humphries rolled his eyes.

“Right. Well, let’s get it over and done with,” he said, opening the car door to a reception of obedient clapping and flashing cameras.

• • •

The teacher walked into the staff room and found Humphries and James sitting alone on the pair of brown plastic chairs that had been provided for them in the corner of the room.

“I am terribly sorry about that,” said the teacher, handing Humphries a tissue from the box she had brought in with her.

Humphries gave a tight smile and stood up. He took the tissue and tried, in vain, to dry the large damp patch of snot on the front of his jacket.

“No need to apologize. I thought they were all utterly charming,” he said with as much enthusiasm as he could muster.

“Well, that’s very understanding of you. He must really like you—I’ve never seen him run up and hug a complete stranger before! I hope it didn’t distract you too much from the performance.”

“No, not at all,” he said, handing James the wet tissue. James took it from him, paused to look around, and, not seeing a bin anywhere, reluctantly put it away in his pocket.

“They’ve been working on that for the last three weeks,” said the teacher proudly. “I’m so glad you liked it. Anything in particular that stood out for you?” she asked.

Humphries hesitated and looked to James who gave a barely visible shrug.

“Yes. Well, the whole thing was marvelous,” he said. The teacher waited for him to elaborate.

Humphries considered telling her that the best bit was when it finished, then quickly thought better of it.

“Hmm. Ah. Yes, I know. I rather enjoyed the part where the donkey hit the angel on the head. I thought the little girl’s tears were most believable.”

“Oh. Well, that really wasn’t planned,” she said, and quickly changed the subject. “Hopefully, the senior pupils will be a little less unpredictable. We’ve assembled everybody in the hall. There’ll be about three hundred students there.”

“And the press?”

“Yes, they’re all there. We’ve set up an area for the cameras and journalists at the side of the hall.”

“Good, good,” said Humphries, looking genuinely pleased for once. “Shall we go through?”

“Yes, of course. Follow me,” said the teacher. She led them out of the room, down the brightly decorated corridor, and through the double doors to face the waiting assembly of students.

Humphries walked in first. He stopped, smiled, and waved slowly, taking in the surroundings. The large hall was packed with children sitting on the wooden floor, all smartly dressed in their maroon uniforms, and the teachers sat in chairs that ran along both sides of the hall, positioned so that they could shoot disapproving glances at any pupil daring to misbehave. Humphries spotted the press area at the front and made his way toward them slowly, a wide, false smile on his face, stopping along the way to shake the hands of students, never taking his eyes off the cameras. He climbed a small set of steps and took a seat at the side of the stage. The headmistress took this as her cue and made her way to the podium.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, it is my pleasure today to welcome Cecil Humphries, the education minister, to our school. Receiving this award is, without a doubt, the single greatest honor that has been bestowed on the school in its one-hundred-twenty-four-year history. Established as an orphanage by Lord Harold . . .”

Humphries stifled a yawn, cocked his head, and tried his best to look interested as the headmistress began a twenty-minute history of the school and its achievements. He felt his eyes grow heavy, but, just as he thought he might not be able to stay awake a second longer, the headmistress turned to face him. He quickly sat up and straightened his tie.

“. . . and so I’d like you all to put your hands together for our esteemed guest, Mr. Cecil Humphries.”

Another round of applause, and Humphries approached the podium. He looked over at the headmistress and gave her his warmest smile (which would be better described as a grimace), then turned back to the audience and cleared his throat.

“Thank you so much for that wonderful introduction. One of the most pleasurable aspects of my job as education minister is to visit schools and see the wonderful achievements of pupils and staff. Today has been no exception, and I thank you all for the warm reception you have given me. It is—”

Humphries was interrupted by a loud ringing sound in his ears. He shook his head and coughed, but the noise persisted. Looking up, Humphries saw the audience watching him expectantly. He tried to ignore the sound and leaned forward toward the microphone.

“Excuse me,” he said, louder than necessary. “As I was saying, it is—” He stopped again. The high-pitched whining was getting louder, and he was finding it difficult to hear himself speak.

“I’m sorry, I seem to—”

He felt his ears start to throb in pain. He clutched his head and pressed at the side of his temples, but the noise kept rising in volume and seemed to expand and press against his skull until he thought it might explode. He reeled backward, struggling to stay standing. Out of the corner of his eye he saw James making his way toward the stage in a half run with a concerned look on his face. The pain was getting worse, and he felt the blood start to rush to his head. He struggled to look calm, aware that the cameras were rolling, but the pressure was building up against his eyes until his eyeballs started pushing out against their sockets. He put his arm out and felt for the side of the podium to try to steady himself, but the room started to spin, and he fell to the ground. He tried to push himself up, but sharp, stabbing pains began to spread across his whole body, each one as if a knife were being pushed into him and then turned slowly.

And then, as suddenly as it had begun, the ringing stopped. Humphries looked around, dazed, and slowly stood up, trying to gather his composure. He heard the sound of a child laughing, and the expression on his face turned from confusion to fury.

“Who is that?” he asked. “Who is laughing?”

Humphries looked out at the audience as the laughter increased in volume, but all he could see were shocked faces.

He turned and saw that James was beside him.

“Nobody is laughing, sir. I think we need to leave,” whispered James, but Humphries didn’t hear him, as the sound of the child’s laughter was joined by the laughter of what sounded like a hundred others.

“They’re all laughing. Stop laughing!” screamed Humphries at the stunned crowd, but instead the sound got increasingly louder until it became unbearable. He fell to the ground once more, his hands clutching his head, the veins on his forehead throbbing intensely from the pressure.

“Arghhh . . . HELP ME!” he shouted, his fear of dying overriding any embarrassment he might have felt at such a public lack of composure.

He looked up and saw a mass of flashing bulbs coming from the press photographers’ pen to his right. Struggling, he turned his head slowly away, his face twisted in agony, and searched the crowd for somebody who could do something to help him. At the front, a teacher stood up and appeared to start shouting for help. All about her, children were crying in fear as they watched Humphries begin to roll around on the floor in agonizing pain, but the sound of them was drowned out by the unbearable noise of children laughing in his head. He felt his temperature begin to rise suddenly and watched helplessly as his hands started to turn purple. Desperately, he looked down from the stage for help and caught the eye of a pale young boy sitting in the front row below him, cross-legged and staring intently at him with an expressionless face.

Humphries froze. It was at that moment, with a sudden jolt of clarity, that he realized what was happening, and panic swept over him. Using all the strength he could muster, he pulled himself to his feet, and, eyes wide with terror and face a mottled purple, he jumped down from the stage and collapsed on the ground as the children in the front row scrambled to get away. The only child who remained was the pale boy in the crisp new uniform, who sat perfectly still and maintained a steady gaze as Humphries crawled forward in his direction, screaming unintelligibly, and then slowly raised his hands toward the boy’s neck. Worry turned to panic as the crowd realized that Humphries was about to attack the child. The headmistress sprang into action, hitched her skirt up, and jumped down from the stage, grabbing the young boy by his shirt collar and dragging him out of harm’s reach. Humphries raised his head slowly and turned to face the cameras. He opened his mouth and screamed,

“INFERNO!”

As soon as the word left his lips, Humphries collapsed to the ground, his eyes open but expressionless, his body quivering in fear, just as he would remain for the rest of his life.

Wednesday, October 17

Cecil Humphries, the government minister for education, despised most things, amongst them:

Cyclists.

The seaside.

Being called by his first name.

Weddings.

The color yellow.

Singing.

But at the top of this list was children. He hated them, which was rather unfortunate given that he was in charge of the well-being of every child in Britain. He knew, however, that the public was rather fond of them, for some reason he couldn’t fathom, and so he had reluctantly accepted the position, sure that it would boost his flagging popularity and take him one step closer toward his ultimate goal: to take the job of his old school friend Prime Minister Edward Banks. Unfortunately for him, the public was far more perceptive than he gave them credit for, and kissing a couple of babies’ heads (then wiping his mouth afterward) had resulted only in a series of frustrating headlines, including:

HUMPHRIES LOVES BABIES

(BUT HE COULDN’T EAT A WHOLE ONE)

The more he tried to improve his image, the more it backfired on him, which only intensified his hatred of anybody under the age of eighteen, if that were at all possible.

It was only fitting, therefore, that the person who would ruin his career and leave him a quivering wreck in a padded cell for the rest of his life would be a twelve-year-old boy.

• • •

The beginning of the end for Cecil Humphries began on an uncharacteristically warm, sunny day in Liverpool. It had been four days since he had been photographed by a well-placed paparazzo stealing chocolate from the hospital bedside of a sick child and only two days since he had been pelted with eggs and flour when the photograph appeared on the front page of every newspaper in the country. Even for someone well accustomed to bad press, this had been a particularly awful week.

Humphries looked out of the window of his chauffeured car, saw the smiling children, and sighed.

“Never work with animals or children. Anyone ever tell you that?” he grumbled. James, his assistant, looked up from his notes, nodded obediently, and said nothing, as he had learned to do.

“Different school, same brats,” he continued as the car pulled up outside the school entrance. “It’s like reliving the same nightmare every single time: a disgusting mass of grubby hands, crying, and runny noses.”

He took out a comb from his jacket pocket and ran it through what remained of his hair.

“You know which ones wind me up the most, though?”

“No, sir,” said James.

“The cute ones. Can’t stand them, with their big eyes and irritating questions.” He shuddered at the thought. “Do try to keep those ones away from me today, would you? I’m really not in the mood.” Humphries adjusted his dark blue tie and leaned over to open the car door.

“What’s the name of this cesspit?” he asked as he pulled back the door handle.

“Perrington School, sir. I briefed you about it earlier.”

“Yes, well, I wasn’t listening. Tell me now,” said Humphries, irritated.

“You’re presenting them with an award for excellence. Also, we’ve invited the press to follow you around while you tour the school and talk to the children. It’ll be a good opportunity for the public to see you in a more, um, positive light. And we’ve been promised a very warm welcome,” explained James.

Humphries rolled his eyes.

“Right. Well, let’s get it over and done with,” he said, opening the car door to a reception of obedient clapping and flashing cameras.

• • •

The teacher walked into the staff room and found Humphries and James sitting alone on the pair of brown plastic chairs that had been provided for them in the corner of the room.

“I am terribly sorry about that,” said the teacher, handing Humphries a tissue from the box she had brought in with her.

Humphries gave a tight smile and stood up. He took the tissue and tried, in vain, to dry the large damp patch of snot on the front of his jacket.

“No need to apologize. I thought they were all utterly charming,” he said with as much enthusiasm as he could muster.

“Well, that’s very understanding of you. He must really like you—I’ve never seen him run up and hug a complete stranger before! I hope it didn’t distract you too much from the performance.”

“No, not at all,” he said, handing James the wet tissue. James took it from him, paused to look around, and, not seeing a bin anywhere, reluctantly put it away in his pocket.

“They’ve been working on that for the last three weeks,” said the teacher proudly. “I’m so glad you liked it. Anything in particular that stood out for you?” she asked.

Humphries hesitated and looked to James who gave a barely visible shrug.

“Yes. Well, the whole thing was marvelous,” he said. The teacher waited for him to elaborate.

Humphries considered telling her that the best bit was when it finished, then quickly thought better of it.

“Hmm. Ah. Yes, I know. I rather enjoyed the part where the donkey hit the angel on the head. I thought the little girl’s tears were most believable.”

“Oh. Well, that really wasn’t planned,” she said, and quickly changed the subject. “Hopefully, the senior pupils will be a little less unpredictable. We’ve assembled everybody in the hall. There’ll be about three hundred students there.”

“And the press?”

“Yes, they’re all there. We’ve set up an area for the cameras and journalists at the side of the hall.”

“Good, good,” said Humphries, looking genuinely pleased for once. “Shall we go through?”

“Yes, of course. Follow me,” said the teacher. She led them out of the room, down the brightly decorated corridor, and through the double doors to face the waiting assembly of students.

Humphries walked in first. He stopped, smiled, and waved slowly, taking in the surroundings. The large hall was packed with children sitting on the wooden floor, all smartly dressed in their maroon uniforms, and the teachers sat in chairs that ran along both sides of the hall, positioned so that they could shoot disapproving glances at any pupil daring to misbehave. Humphries spotted the press area at the front and made his way toward them slowly, a wide, false smile on his face, stopping along the way to shake the hands of students, never taking his eyes off the cameras. He climbed a small set of steps and took a seat at the side of the stage. The headmistress took this as her cue and made her way to the podium.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, it is my pleasure today to welcome Cecil Humphries, the education minister, to our school. Receiving this award is, without a doubt, the single greatest honor that has been bestowed on the school in its one-hundred-twenty-four-year history. Established as an orphanage by Lord Harold . . .”

Humphries stifled a yawn, cocked his head, and tried his best to look interested as the headmistress began a twenty-minute history of the school and its achievements. He felt his eyes grow heavy, but, just as he thought he might not be able to stay awake a second longer, the headmistress turned to face him. He quickly sat up and straightened his tie.

“. . . and so I’d like you all to put your hands together for our esteemed guest, Mr. Cecil Humphries.”

Another round of applause, and Humphries approached the podium. He looked over at the headmistress and gave her his warmest smile (which would be better described as a grimace), then turned back to the audience and cleared his throat.

“Thank you so much for that wonderful introduction. One of the most pleasurable aspects of my job as education minister is to visit schools and see the wonderful achievements of pupils and staff. Today has been no exception, and I thank you all for the warm reception you have given me. It is—”

Humphries was interrupted by a loud ringing sound in his ears. He shook his head and coughed, but the noise persisted. Looking up, Humphries saw the audience watching him expectantly. He tried to ignore the sound and leaned forward toward the microphone.

“Excuse me,” he said, louder than necessary. “As I was saying, it is—” He stopped again. The high-pitched whining was getting louder, and he was finding it difficult to hear himself speak.

“I’m sorry, I seem to—”

He felt his ears start to throb in pain. He clutched his head and pressed at the side of his temples, but the noise kept rising in volume and seemed to expand and press against his skull until he thought it might explode. He reeled backward, struggling to stay standing. Out of the corner of his eye he saw James making his way toward the stage in a half run with a concerned look on his face. The pain was getting worse, and he felt the blood start to rush to his head. He struggled to look calm, aware that the cameras were rolling, but the pressure was building up against his eyes until his eyeballs started pushing out against their sockets. He put his arm out and felt for the side of the podium to try to steady himself, but the room started to spin, and he fell to the ground. He tried to push himself up, but sharp, stabbing pains began to spread across his whole body, each one as if a knife were being pushed into him and then turned slowly.

And then, as suddenly as it had begun, the ringing stopped. Humphries looked around, dazed, and slowly stood up, trying to gather his composure. He heard the sound of a child laughing, and the expression on his face turned from confusion to fury.

“Who is that?” he asked. “Who is laughing?”

Humphries looked out at the audience as the laughter increased in volume, but all he could see were shocked faces.

He turned and saw that James was beside him.

“Nobody is laughing, sir. I think we need to leave,” whispered James, but Humphries didn’t hear him, as the sound of the child’s laughter was joined by the laughter of what sounded like a hundred others.

“They’re all laughing. Stop laughing!” screamed Humphries at the stunned crowd, but instead the sound got increasingly louder until it became unbearable. He fell to the ground once more, his hands clutching his head, the veins on his forehead throbbing intensely from the pressure.

“Arghhh . . . HELP ME!” he shouted, his fear of dying overriding any embarrassment he might have felt at such a public lack of composure.

He looked up and saw a mass of flashing bulbs coming from the press photographers’ pen to his right. Struggling, he turned his head slowly away, his face twisted in agony, and searched the crowd for somebody who could do something to help him. At the front, a teacher stood up and appeared to start shouting for help. All about her, children were crying in fear as they watched Humphries begin to roll around on the floor in agonizing pain, but the sound of them was drowned out by the unbearable noise of children laughing in his head. He felt his temperature begin to rise suddenly and watched helplessly as his hands started to turn purple. Desperately, he looked down from the stage for help and caught the eye of a pale young boy sitting in the front row below him, cross-legged and staring intently at him with an expressionless face.

Humphries froze. It was at that moment, with a sudden jolt of clarity, that he realized what was happening, and panic swept over him. Using all the strength he could muster, he pulled himself to his feet, and, eyes wide with terror and face a mottled purple, he jumped down from the stage and collapsed on the ground as the children in the front row scrambled to get away. The only child who remained was the pale boy in the crisp new uniform, who sat perfectly still and maintained a steady gaze as Humphries crawled forward in his direction, screaming unintelligibly, and then slowly raised his hands toward the boy’s neck. Worry turned to panic as the crowd realized that Humphries was about to attack the child. The headmistress sprang into action, hitched her skirt up, and jumped down from the stage, grabbing the young boy by his shirt collar and dragging him out of harm’s reach. Humphries raised his head slowly and turned to face the cameras. He opened his mouth and screamed,

“INFERNO!”

As soon as the word left his lips, Humphries collapsed to the ground, his eyes open but expressionless, his body quivering in fear, just as he would remain for the rest of his life.

Reading Group Guide

A Reading Group Guide to

The Ability

By M. M. Vaughan

Discussion Questions

1. What is a prologue and what importance is the prologue to this particular story?

2. What was your first impression of Christopher Lane when he was introduced in the story, sitting in the school office waiting for the principal? Use descriptions from the book to support your answer. Did your impression of Christopher change as the story progressed? Why or why not?

3. What was the author’s purpose for including the scene where Christopher interacts with a spider spinning its web?

4. Christopher stole some money from his teacher. What does Christopher do with the money? How had Christopher and his mother been surviving the past seven years since his father’s death?

5. Christopher attempted to sell his father’s war medals at a pawnshop. What was Frank’s (the pawnshop owner) impression of Christopher? Compare and contrast your impression of Christopher to Frank’s. What did Frank see in Christopher that led Frank to lend him money in advance for work yet to be done? Was it possible that Christopher unknowingly was using his Ability on Frank?

6. Describe Christopher’s mother. What do you think is wrong with her? At twelve years of age, should Christopher be responsible for his mother’s actions?

7. While Chris attended the Black Marsh Secondary School, he was bullied by Kevin and four other boys. During one confrontation, Chris unwittingly discovered one of his abilities, as he was able to levitate Kevin across the room. Was a two-month suspension an acceptable punishment for Chris? What about the constant bullying Chris experienced at the hands of Kevin and his friends? Who else at the school could be considered a bully?

8. The school administration was aware of Chris’s home life as Miss Sonata had been warned about Chris’s home situation. Chris was only twelve years old, and his father had died when he was five years old. Was the school obligated in any way to help Chris? Could they have helped to find social services for Christopher and his mother?

9. Miss Sonata informed Chris that at Myers Holt Academy, Center for Excellence, they weren’t interested in how he was doing in school. They valued certain skills more than academic results. Skills such as imagination, observational skills, and empathy were important. They believed one makes the most progress if one works on the way one thinks rather than on the facts one knows. Is our educational system designed for only one way of thinking? In what ways do you think we could improve our educational system?

10. For what other purpose besides bodyguards does the author use the characters Ron and John? Use examples from the book to support your ideas.

11. Did the offer of going to school at Myers Holt sound too good to be true? Why or why not? All clothes, books, food, and excellent teachers were provided in exchange for not telling anyone of the work the students did at the school. Discretion was necessary because the methods used were unique and could be misused. If this was true, was it appropriate for Chris, at age twelve, to make such an important decision? Discuss the Official Secrets Act the students were required to sign. Did the students really understand what they were signing?

12. What kind of relationship exists between Chris and his mother? Does his mother love him? Does he love his mother? After Chris was accepted into Myers Holt Academy and turned down the opportunity to attend the school, did their argument change their relationship?

13. Compare how Chris was treated by the staff at Myers Holt Academy to how he was treated at home. Where did he feel the most comfortable? What constitutes a family?

14. While Chris was learning about his Ability he was told that the more power one had naturally, the more harm one could do with it. He would have to learn how to control it. When Chris got angry his natural Ability was stronger than others, and the possibility of someone getting hurt increased. Consider his confrontation with Kevin at Black Marsh Secondary School and his encounter with Mortimer during the Antarctic Ball. Even when he wasn’t angry, Chris had little control. Consider his lesson with Cassandra when he used a candle flame and caused an explosion, and the time he lifted John up in the air and crashed him against the ceiling. Is learning control, and having self-discipline, easier for some people than others?

15. Sir Bentley gave a warning to the students: “You must never, never use the Ability on one another. Or on any person, for that matter, unless you have a teacher with you. Do you have any idea how powerful Ability is?” Did the students understand the power they had? Can you think of a better way for Sir Bentley to demonstrate to the students how powerful they were so that they would understand? How does this warning relate to Chris later in the story when he is fighting Mortimer? There were teachers present, but were they able to help Chris? Did Chris overstep his bounds by attacking Mortimer, or was he justified in using his Ability as it was intended? How did Chris feel as he realized he had no control over what was happening to Mortimer and couldn’t stop his powers?

16. Another warning given to the students was that they should not try to use the Ability on the staff as they have all been trained to block entry into their minds. Chris’s natural ability did, by accident, allow him to access Ms. Lamb’s mind. Was Ms. Lamb’s revenge against Chris, asking the other students to find out what his most embarrassing moment was, an ethical lesson to teach?

17. How dangerous is the Ability in inexperienced twelve-year-olds? There were many instances when Chris lost control of his Ability. What about the other students? Did they also have problems controlling their Ability? Did the school have the time to correctly teach them how to use and control their individual Ability before they were required to work? How had the teachers improved their teaching skills to help the students learn control and how to use their Ability since the academy was closed thirty years before?

18. What is your opinion on the use of the dog Hermes for the students to practice on to learn how to command someone to do exactly what they wanted? Implanting thoughts into someone’s mind was the most difficult thing to do with the Ability. How is this different from what is known as brainwashing?

19. Sir Bentley instructed the students on how to stop someone from trying to perform Inferno. It was not a practice lesson, meaning the students could not actually perform the exercise. Is there a difference in learning by doing versus learning by books and lectures? Are there different styles of learning? Which style of learning do you prefer?

20. How do you explain Chris’s insistence on sneaking out of Myers Holt Academy to pay a debt to Frank, the pawnshop owner, when he was specifically instructed not to do so? Chris broke his promise to Sir Bentley and lied to Ron and Jon in order to repay his promise to Frank. Why would Chris jeopardize his new life by repaying this debt? Was using his Ability to pay for his taxi rides to and from the academy an ethical thing to do? What does this say about Chris’s character and his integrity?

21. How did John help Ron to understand Chris and his transgressions with security?

22. Describe the relationship between Ernest and his brother, Mortimer. How does this relationship compare to the relationship between Ernest and his mother? How would you describe Dulcia Genever? Does your opinion of Dulcia change after you learn what she thought of Ernest and Mortimer once Ernest was caught at the Antarctic Ball? Why or why not?

23. Sir Bentley had given very specific instructions to security on how to proceed with the imprisonment of the captured boy from the photograph. Where did the miscommunication happen that allowed Ernest to escape?

24. In times of emergency does one forget fear and just do what needs to be done? Did all the practicing the students did help them?

25. Discuss how the student’s teamwork helped contain the chaos at the Antarctic Ball and prevent serious injury to the honored guests and visitors at the ball.

26. Was Mortimer’s death Chris’s fault? Why or why not? Could others have prevented the death? If so, what could they have done differently?

27. As Chris waited to go home for the holidays, he was surprised by how sad he was to leave his school and classmates. He watched as the others were picked up by their families. When he arrived home he was not greeted with hugs and smiles but a gruff, “Turn the television back on and get me a cup of tea” from his mother. Are all families loving and happy? What was Ernest’s family like? Did Chris’s and Ernest’s families have anything in common?

28. Throughout the story it was mentioned that other countries also knew about the Ability. Some countries had even experimented with trying to kill people using the Ability. A person’s survival instinct automatically kicked in and created a block. Instead of killing a person, a technique was discovered called Inferno, which damages a person for life. Since only twelve-year-olds are capable of performing Inferno, would this be an ethical skill to teach a student? Do other countries have the same standards as we do? How could an international community control such teachings? What did Sir Bentley teach the students at Myers Holt Academy?

Activities

1. What part of Myers Holt Academy is your favorite? Use descriptions from the book to show evidence of your choice. Write an essay about Myers Holt Academy as if you were a student there and showing a new student the school. What would you tell the student was the best part of the school?

2. Go to the library or research online to learn about jellyfish. Is there a reason why the pulsating of the jellyfish is supposed to be calming?

3. Is it a fact that fear reduces performance? Search the Internet for any information that may confirm or disprove this theory.

4. Research telekinesis using the Internet or a library. How would you define it? Is there any basis for this ability to move objects by mental power?

5. Write a press release from the Prime Minister’s office explaining the unusual activities that occurred at the Antarctic Ball. Topics to be explained could include a mumbling prime minister, flying children, incapacitated security guards, and two deaths.

6. Make a chart comparing the different Abilities of the students at Myers Holt Academy. Make another chart of the students who were at Myers Holt Academy thirty years ago. How do these two teams of students compare to each other?

7. Research the definition of revenge. To seek revenge for Mortimer’s life, does Ernest need to kill Christopher Lane? Make a prediction about how Ernest will seek revenge against Christopher.

8. Read aloud the scene between Ernest and Mortimer when Ernest was presented a kitten as a motivational tool to improve his Ability. Discuss Ernest’s strengths in dealing with the situation.

9. Draw the cityscape of your own mind and design it in a way that reflects your personality, knowledge and interest. Think about the style of architecture. What would be the tallest building in your mind? The smallest?

Guide prepared by Lynn Dobson, librarian at East Brookfield Elementary School, East Brookfield, MA.

This guide, written to align with the Common Core State Standards (www.corestandards.org) has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

The Ability

By M. M. Vaughan

Discussion Questions

1. What is a prologue and what importance is the prologue to this particular story?

2. What was your first impression of Christopher Lane when he was introduced in the story, sitting in the school office waiting for the principal? Use descriptions from the book to support your answer. Did your impression of Christopher change as the story progressed? Why or why not?

3. What was the author’s purpose for including the scene where Christopher interacts with a spider spinning its web?

4. Christopher stole some money from his teacher. What does Christopher do with the money? How had Christopher and his mother been surviving the past seven years since his father’s death?

5. Christopher attempted to sell his father’s war medals at a pawnshop. What was Frank’s (the pawnshop owner) impression of Christopher? Compare and contrast your impression of Christopher to Frank’s. What did Frank see in Christopher that led Frank to lend him money in advance for work yet to be done? Was it possible that Christopher unknowingly was using his Ability on Frank?

6. Describe Christopher’s mother. What do you think is wrong with her? At twelve years of age, should Christopher be responsible for his mother’s actions?

7. While Chris attended the Black Marsh Secondary School, he was bullied by Kevin and four other boys. During one confrontation, Chris unwittingly discovered one of his abilities, as he was able to levitate Kevin across the room. Was a two-month suspension an acceptable punishment for Chris? What about the constant bullying Chris experienced at the hands of Kevin and his friends? Who else at the school could be considered a bully?

8. The school administration was aware of Chris’s home life as Miss Sonata had been warned about Chris’s home situation. Chris was only twelve years old, and his father had died when he was five years old. Was the school obligated in any way to help Chris? Could they have helped to find social services for Christopher and his mother?

9. Miss Sonata informed Chris that at Myers Holt Academy, Center for Excellence, they weren’t interested in how he was doing in school. They valued certain skills more than academic results. Skills such as imagination, observational skills, and empathy were important. They believed one makes the most progress if one works on the way one thinks rather than on the facts one knows. Is our educational system designed for only one way of thinking? In what ways do you think we could improve our educational system?

10. For what other purpose besides bodyguards does the author use the characters Ron and John? Use examples from the book to support your ideas.

11. Did the offer of going to school at Myers Holt sound too good to be true? Why or why not? All clothes, books, food, and excellent teachers were provided in exchange for not telling anyone of the work the students did at the school. Discretion was necessary because the methods used were unique and could be misused. If this was true, was it appropriate for Chris, at age twelve, to make such an important decision? Discuss the Official Secrets Act the students were required to sign. Did the students really understand what they were signing?

12. What kind of relationship exists between Chris and his mother? Does his mother love him? Does he love his mother? After Chris was accepted into Myers Holt Academy and turned down the opportunity to attend the school, did their argument change their relationship?

13. Compare how Chris was treated by the staff at Myers Holt Academy to how he was treated at home. Where did he feel the most comfortable? What constitutes a family?

14. While Chris was learning about his Ability he was told that the more power one had naturally, the more harm one could do with it. He would have to learn how to control it. When Chris got angry his natural Ability was stronger than others, and the possibility of someone getting hurt increased. Consider his confrontation with Kevin at Black Marsh Secondary School and his encounter with Mortimer during the Antarctic Ball. Even when he wasn’t angry, Chris had little control. Consider his lesson with Cassandra when he used a candle flame and caused an explosion, and the time he lifted John up in the air and crashed him against the ceiling. Is learning control, and having self-discipline, easier for some people than others?

15. Sir Bentley gave a warning to the students: “You must never, never use the Ability on one another. Or on any person, for that matter, unless you have a teacher with you. Do you have any idea how powerful Ability is?” Did the students understand the power they had? Can you think of a better way for Sir Bentley to demonstrate to the students how powerful they were so that they would understand? How does this warning relate to Chris later in the story when he is fighting Mortimer? There were teachers present, but were they able to help Chris? Did Chris overstep his bounds by attacking Mortimer, or was he justified in using his Ability as it was intended? How did Chris feel as he realized he had no control over what was happening to Mortimer and couldn’t stop his powers?

16. Another warning given to the students was that they should not try to use the Ability on the staff as they have all been trained to block entry into their minds. Chris’s natural ability did, by accident, allow him to access Ms. Lamb’s mind. Was Ms. Lamb’s revenge against Chris, asking the other students to find out what his most embarrassing moment was, an ethical lesson to teach?

17. How dangerous is the Ability in inexperienced twelve-year-olds? There were many instances when Chris lost control of his Ability. What about the other students? Did they also have problems controlling their Ability? Did the school have the time to correctly teach them how to use and control their individual Ability before they were required to work? How had the teachers improved their teaching skills to help the students learn control and how to use their Ability since the academy was closed thirty years before?

18. What is your opinion on the use of the dog Hermes for the students to practice on to learn how to command someone to do exactly what they wanted? Implanting thoughts into someone’s mind was the most difficult thing to do with the Ability. How is this different from what is known as brainwashing?

19. Sir Bentley instructed the students on how to stop someone from trying to perform Inferno. It was not a practice lesson, meaning the students could not actually perform the exercise. Is there a difference in learning by doing versus learning by books and lectures? Are there different styles of learning? Which style of learning do you prefer?

20. How do you explain Chris’s insistence on sneaking out of Myers Holt Academy to pay a debt to Frank, the pawnshop owner, when he was specifically instructed not to do so? Chris broke his promise to Sir Bentley and lied to Ron and Jon in order to repay his promise to Frank. Why would Chris jeopardize his new life by repaying this debt? Was using his Ability to pay for his taxi rides to and from the academy an ethical thing to do? What does this say about Chris’s character and his integrity?

21. How did John help Ron to understand Chris and his transgressions with security?

22. Describe the relationship between Ernest and his brother, Mortimer. How does this relationship compare to the relationship between Ernest and his mother? How would you describe Dulcia Genever? Does your opinion of Dulcia change after you learn what she thought of Ernest and Mortimer once Ernest was caught at the Antarctic Ball? Why or why not?

23. Sir Bentley had given very specific instructions to security on how to proceed with the imprisonment of the captured boy from the photograph. Where did the miscommunication happen that allowed Ernest to escape?

24. In times of emergency does one forget fear and just do what needs to be done? Did all the practicing the students did help them?

25. Discuss how the student’s teamwork helped contain the chaos at the Antarctic Ball and prevent serious injury to the honored guests and visitors at the ball.

26. Was Mortimer’s death Chris’s fault? Why or why not? Could others have prevented the death? If so, what could they have done differently?

27. As Chris waited to go home for the holidays, he was surprised by how sad he was to leave his school and classmates. He watched as the others were picked up by their families. When he arrived home he was not greeted with hugs and smiles but a gruff, “Turn the television back on and get me a cup of tea” from his mother. Are all families loving and happy? What was Ernest’s family like? Did Chris’s and Ernest’s families have anything in common?

28. Throughout the story it was mentioned that other countries also knew about the Ability. Some countries had even experimented with trying to kill people using the Ability. A person’s survival instinct automatically kicked in and created a block. Instead of killing a person, a technique was discovered called Inferno, which damages a person for life. Since only twelve-year-olds are capable of performing Inferno, would this be an ethical skill to teach a student? Do other countries have the same standards as we do? How could an international community control such teachings? What did Sir Bentley teach the students at Myers Holt Academy?

Activities

1. What part of Myers Holt Academy is your favorite? Use descriptions from the book to show evidence of your choice. Write an essay about Myers Holt Academy as if you were a student there and showing a new student the school. What would you tell the student was the best part of the school?

2. Go to the library or research online to learn about jellyfish. Is there a reason why the pulsating of the jellyfish is supposed to be calming?

3. Is it a fact that fear reduces performance? Search the Internet for any information that may confirm or disprove this theory.

4. Research telekinesis using the Internet or a library. How would you define it? Is there any basis for this ability to move objects by mental power?

5. Write a press release from the Prime Minister’s office explaining the unusual activities that occurred at the Antarctic Ball. Topics to be explained could include a mumbling prime minister, flying children, incapacitated security guards, and two deaths.

6. Make a chart comparing the different Abilities of the students at Myers Holt Academy. Make another chart of the students who were at Myers Holt Academy thirty years ago. How do these two teams of students compare to each other?

7. Research the definition of revenge. To seek revenge for Mortimer’s life, does Ernest need to kill Christopher Lane? Make a prediction about how Ernest will seek revenge against Christopher.

8. Read aloud the scene between Ernest and Mortimer when Ernest was presented a kitten as a motivational tool to improve his Ability. Discuss Ernest’s strengths in dealing with the situation.

9. Draw the cityscape of your own mind and design it in a way that reflects your personality, knowledge and interest. Think about the style of architecture. What would be the tallest building in your mind? The smallest?

Guide prepared by Lynn Dobson, librarian at East Brookfield Elementary School, East Brookfield, MA.

This guide, written to align with the Common Core State Standards (www.corestandards.org) has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

About The Illustrator

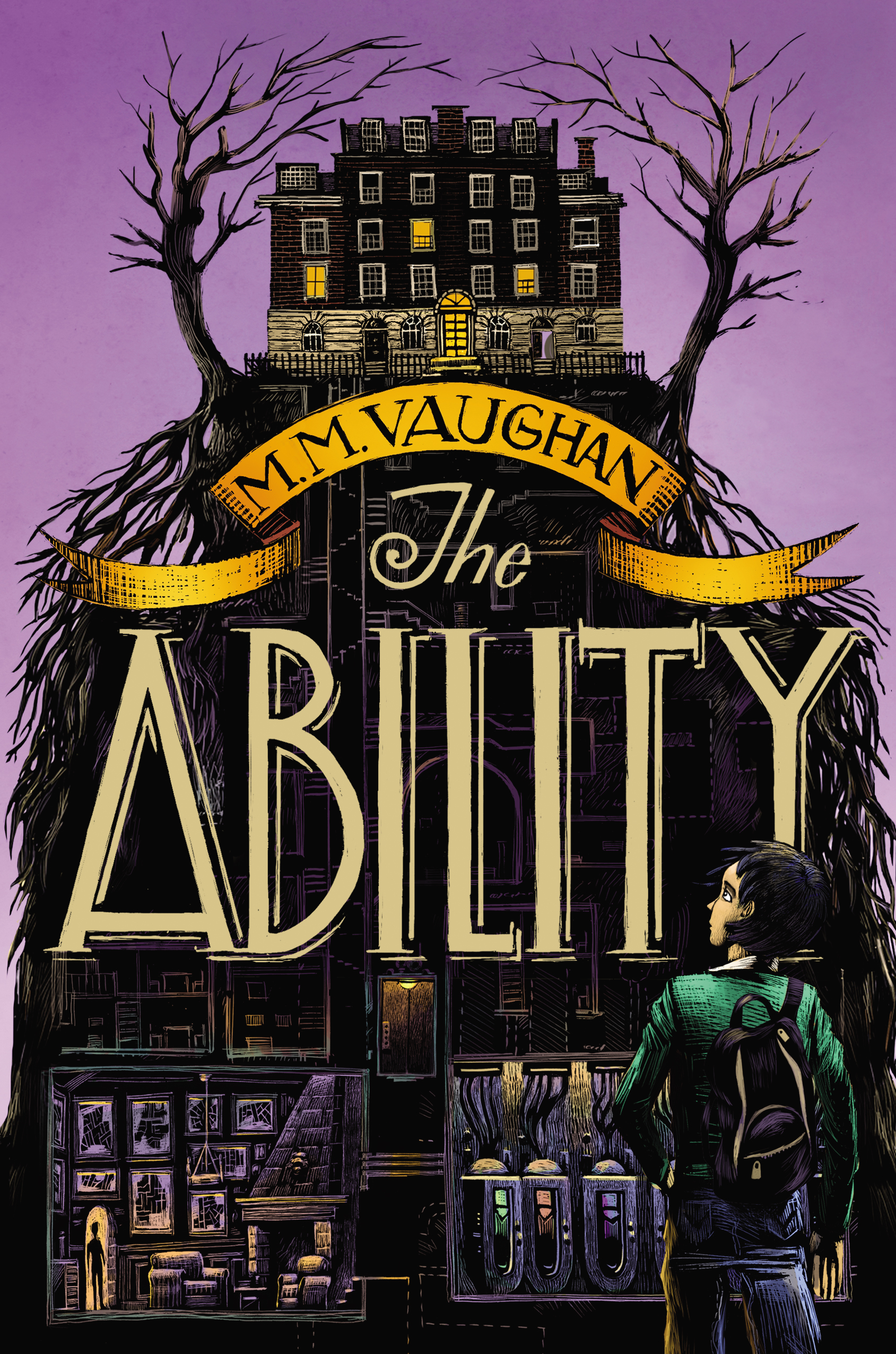

Iacopo Bruno

Iacopo Bruno is an illustrator and graphic designer living in Milan, Italy.

Product Details

- Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books (April 23, 2013)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442452008

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 920L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Raves and Reviews

“Readers will enjoy the candy-shop wish fulfillment in this fast-paced, superhero-tinged spy novel. With its comics-style origin stories and vows of revenge, this first book in a planned series has an intriguing concept that could hit a middle-grade sweet spot.”

– Publishers Weekly

“Mystery intertwined with fantasy, and chapters arranged by date, give urgency to the

fantasy-mystery-action hybrid.”

– Booklist

Awards and Honors

- Maine Student Book Award Reading List

- MSTA Reading Circle List

Resources and Downloads

Activity Sheets

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Ability Hardcover 9781442452008(3.2 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): M.M. Vaughan Photograph courtesy of the author(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit