Table of Contents

About The Book

A timely and captivating novel about a mother whose life spirals out of control when she descends into alcoholism, and her battle to get sober and regain custody of her beloved son.

Cadence didn’t sit down one night and decide that downing two bottles of wine was a brilliant idea.

Her drinking snuck up on her—as a way to sleep, to help her relax after a long day, to relieve some of the stress of the painful divorce that’s left her struggling to make ends meet with her five-year old son, Charlie.

It wasn’t always like this. Just a few years ago, Cadence seemed to have it all—a successful husband, an adorable son, and a promising career as a freelance journalist. But with the demise of her marriage, her carefully constructed life begins to spiral out of control. Suddenly she is all alone trying to juggle the demands of work and motherhood.

Logically, Cadence knows that she is drinking too much, and every day begins with renewed promises to herself that she will stop. But within a few hours, driven by something she doesn’t understand, she is reaching for the bottle—even when it means not playing with her son because she is too tired, or dropping him off at preschool late, again. And even when one calamitous night it means leaving him alone to pick up more wine at the grocery store. It’s only when her ex-husband shows up at her door to take Charlie away that Cadence realizes her best kept secret has been discovered….

Heartbreaking, haunting, and ultimately life-affirming, Best Kept Secret is more than just the story of Cadence—it’s a story of how the secrets we hold closest are the ones that can most tear us apart.

Cadence didn’t sit down one night and decide that downing two bottles of wine was a brilliant idea.

Her drinking snuck up on her—as a way to sleep, to help her relax after a long day, to relieve some of the stress of the painful divorce that’s left her struggling to make ends meet with her five-year old son, Charlie.

It wasn’t always like this. Just a few years ago, Cadence seemed to have it all—a successful husband, an adorable son, and a promising career as a freelance journalist. But with the demise of her marriage, her carefully constructed life begins to spiral out of control. Suddenly she is all alone trying to juggle the demands of work and motherhood.

Logically, Cadence knows that she is drinking too much, and every day begins with renewed promises to herself that she will stop. But within a few hours, driven by something she doesn’t understand, she is reaching for the bottle—even when it means not playing with her son because she is too tired, or dropping him off at preschool late, again. And even when one calamitous night it means leaving him alone to pick up more wine at the grocery store. It’s only when her ex-husband shows up at her door to take Charlie away that Cadence realizes her best kept secret has been discovered….

Heartbreaking, haunting, and ultimately life-affirming, Best Kept Secret is more than just the story of Cadence—it’s a story of how the secrets we hold closest are the ones that can most tear us apart.

Excerpt

Best Kept Secret One

Being drunk in front of your child is right up there on the Big Bad No-no List of Motherhood. I knew what I was doing was wrong. I knew it with every glass, every swallow, every empty bottle thrown into the recycle bin. I hated drinking. I hated it . . . and I couldn’t stop. The anesthetic effect of alcohol ran thick in my blood; the Great Barrier Reef built between me and my feelings. I watched myself do it in an out-of-body experience: Oh, isn’t this interesting? Look at me, the sloppy drunk. It snuck up on me, every time. It took me by surprise.

I tried to stop. Of course I tried. I went a day, maybe two, before the urge burned strong enough, it rose in my throat like a gnarled hand reaching for a drink. My body ached. My brain sloshed against the inside of my skull. The more I loathed drinking, the more I needed it to find that sweet spot between awareness and agony. Even now, even though it has been sixty-four days since I have taken a drink, the shame clings to me. It sickens my senses worse than any hangover I’ve ever suffered.

It’s early April, and I drive down a street lined with tall, sturdy maples. Gauzelike clouds stretch across the icy blue sky. A few earnest men stand in front of their houses appraising the state of their lawns. My own yard went to hell while I was away and I have not found time nor inclination to be its savior.

Any other day I would have found this morning beautiful. Any other day I might have stopped to stare at the sky, to enjoy the fragile warmth of the sun on my skin. Today is not any other day. Today marks two months and four days since I have seen my son. Each corner I turn takes me closer and closer to picking him up from his grandmother’s house. For now, it was decided this arrangement was better than my coming face-to-face with Martin, his father.

“What do they think will happen?” I’d asked my treatment counselor, Andi, when the rules of visitation came down. My voice was barely above a whisper. “What do they think I’d do?”

“Think of how many times you were drunk around Charlie,” she said. “There’s reason for concern.”

I sat a moment, contemplating this dangerous little bomb, vacillating between an attempt to absorb the truth behind her words and the desire to find a way to hide from it. I kept my eyes on the floor, too afraid of what I’d see if I looked into hers. Two weeks in the psych ward rendered me incapable of pulling off my usually dazzling impersonation of a happy, successful, single mother. Andi knew I was drunk in front of Charlie every day for over a year. She’d heard me describe the misery etched across my child’s face each time I pulled the cork on yet another bottle of wine. She knew the damage I’d done.

“Cadence?” she prodded.

Finally, I managed to look up at her round, pretty face. For the most part, I like Andi, except when she suggests I might be wrong about something. In the two months I have known her, this has happened more often than I’d like.

She met my gaze and smiled softly. I didn’t respond, so she spoke again. “Try to think about it as what’s best for Charlie.”

“Isn’t it best for Charlie to see his parents get along?” I asked. I’ve read enough advice books on how divorced parents should act in front of their children to feel pretty confident I was right about this one. I longed to stand before Martin and put on the face that said everything was okay. I wanted to prove to him that whatever darkness had reared its ugly head inside me had subsided; I had it back under control.

“Yes, seeing you getting along would be best,” Andi conceded. “But it’s not realistic. Martin just filed to take custody away from you. Your emotions are running insanely high. Even with the best intentions it would be hard not to confront him.”

“I don’t want to confront Martin,” I said. “I just want to talk to him. Explain that I’m better. That I’m getting help with this . . . problem.”

“Pleading your case is just going to stir up a bunch of negativity. Charlie is five years old. Even if you manage to restrain yourself from fighting, he’s smart enough to pick up on facial expressions and the tone of your voices. You don’t want to upset him.”

“I could fake it,” I said. I knew it wouldn’t take much. When we were married, Martin and I fought and then went to bed with an invisible force field between us. In the morning, I gave him a smile, a kiss, and then made a pot of coffee and his lunch. Shape-shifting into what made Martin happy was something I already knew how to do.

Andi looked at me with her gentle, tigerlike topaz eyes. “Have you considered that maybe ‘faking it’ is what got you here?”

I was eight months pregnant when Martin and I decided I would leave my reporting job at the Seattle Herald. I’m not sure where I got the idea that working from home while taking care of an infant would be easy; I guess I thought freelance writing would grant me flexibility and plenty of free time to be with my son. Of course, after spending three years juggling the incessant demands of both self-employment and motherhood, I realized there was nothing easy about it. There was one person in charge of my day, and his name was Charlie.

“Mama!” he said, jumping on my bed one morning in May, a few months before he turned four. “Time to wake up!”

I groaned, rolled over beneath the covers, and peeked at the clock. Six o’clock on a Sunday. Oh, sweet Jesus. “Charlie, honey, can you go back to bed? It’s too early.”

“No, it’s not!” He bounced on the mattress, jarring my throbbing head. Finishing off that bottle of merlot had been a bad idea. Since Martin moved out the previous November, my usual limit was one glass, maybe two a night, and then it was only to help me sleep. But then the night before, with Charlie already down for the count, I figured it wouldn’t hurt to enjoy another glass while I worked. When the contents of my cup grew low, I splashed in a little more to top it off. Before I knew it, there was none left to pour.

Now, I propped myself up on my elbows and looked at my son through scratchy, dry eyes. He was starting to lose his babyish looks—his dark, wispy curls were mussed, his cheeks were pink, and his ears stuck out from his head like a chimpanzee’s. My little monkey.

“Do you want to cuddle with me for a while?” I asked, hoping he’d take the bait.

“No!” Charlie said. “I want pancakes. And yogurt.”

I flopped back down and threw my forearm over my eyes, causing the pain to ricochet like a bullet beneath my skull. If I didn’t do something for this headache soon, it would take over and I’d never get anything written today. I had barely started my article on the Northwest’s Top Ten Bed-and-Breakfasts for Seattle magazine, and while it was originally due the week before, I managed to sweet-talk the editor into extending my deadline through tomorrow. I couldn’t afford to screw up and not get paid.

Charlie pushed me playfully and giggled. He was not going to give up.

I sighed and forced myself to rotate up and out of bed. The room spun around me, so I kept my eyes closed and took deep breaths until it passed. Ugh. I felt awful. I hoped I wouldn’t be sick.

“Pancakes!” Charlie hollered, and I cringed, clutching my forehead with one hand.

“Shh, honey. Mama has a headache.”

He leapt off the bed and sped down the hall in his Spider-Man pajamas. The noisy clamor of cartoons quickly echoed throughout the house.

I trodded after him, my bare feet slapping against the hardwood floors. I wondered when I had changed out of my jeans and into my pajamas the night before; I didn’t remember doing it. I must have been really tired, I thought hazily. I’m really not getting enough sleep.

In my tiny, black-and-white, fifties-style kitchen, I immediately went for the super-size bottle of Advil on the counter and shook four out into my hand. I popped them into my mouth and used my cupped palm beneath the faucet to splash them down with a water chaser.

I fought with the coffee filters for a minute, but soon managed to get a pot brewing, throwing in an extra scoop of aromatic grounds for a super-charged medicinal kick of caffeine. Charlie raced in from the living room and threw his arms around my legs, squeezing them tightly.

“I love you, Mama,” he said.

“I love you, too, Charlie bear.” I hoped my voice didn’t sound as weary as I felt. I reached around and cupped my hand against the curve of his head.

He let go of me, padded over to the refrigerator, and grabbed a strawberry yogurt from the bottom shelf. I kept most of his snacks within reach so he could get them himself. I’d read somewhere that giving him tasks like this to accomplish on his own would encourage his self-esteem. It also reduced the number of things I needed to do for him each day from one hundred to ninety-nine.

“Did you turn off the TV?” I asked absentmindedly, then realized the sound of cartoons had ceased.

“Yep!” He sat at the chrome-legged, black Formica kitchen table that put in double duty as my desk. The house was too small for an office, so my laptop and printer took up one end of the table, and at meal time Charlie and I took up the other. It was all the space I needed, really, since most of my work was done online and over the phone.

“Let me get you a spoon,” I said, reaching into the silverware drawer and setting the utensil on the table. “Eating yogurt with your fingers isn’t such a hot idea.”

With an impish grin, he wiggled his fingers threateningly over the open cup.

“Don’t you dare,” I said. Too late. He dropped his fingers in the creamy pink yogurt and scooped a bite into his mouth.

“Charlie,” I said, exasperated. “No.” I snatched a dish towel from the counter, took him by the wrist, and wiped his hand clean. I gave the bottom of his chin a gentle pinch. “Don’t do that again, okay? You’re a big boy. You know better than that.”

“Okay,” he said. He dutifully picked up his spoon and began to eat. My head screamed at me to go back to bed, but I knew it would be impossible.

While I inhaled my coffee from a black, soup bowl-size mug, I zapped a few frozen pancakes in the microwave. When they were done, I cut them up into bite-size squares and served them to my son. I nibbled on one without butter or syrup, hoping the carbs would take the edge off my nausea.

“All done!” Charlie said, pushing away from the table and jumping down from his chair. “Want to come play with me?”

I smiled at him. “I need to work for a little while. Can you watch TV quietly?”

“But I want you to play,” he whined, yanking on my hand.

I took a deep breath, then exhaled. That was that. As always, work would have to wait for his nap time. I knew spending time with my son was more important, but the money I’d received in the divorce settlement wasn’t going to last forever. If I watched my pennies and pulled in at least a little bit from freelancing, it would be enough to live on for a couple of years. Martin paid child support to cover basic things like Charlie’s clothes and food, but in order to survive on my own long term, I needed to step up my professional game. Something that was difficult to do, considering I wasn’t all that crazy about freelance journalism in the first place. After I left the Herald, my career had morphed into a matter of convenience rather than a passionate pursuit, but it was all I knew how to do. So for the time being, I didn’t have a choice but to make it work.

“Mama!” Charlie said, jerking on my hand again. I allowed him to lead me into the living room, a small space made to look even smaller by the arrangement of an overstuffed khaki love seat and two matching, comfy lounge chairs with ottomans. There was a flat-screen television hanging above the river-stone fireplace—an indulgence Martin encouraged before he moved out, a purchase I reluctantly grew to enjoy. The built-in cherry shelves on each side of the fireplace were stuffed with my books, a few candles and pictures, but mostly Charlie’s toys.

He let go of my hand and ran over to the enormous pile of brightly hued Duplo blocks that already lay in the middle of the tan, skeleton leaf-imprinted area rug. He sat down and gave me a toothy grin.

“Here,” Charlie said, holding out a single red block. “This is yours. Mine are the rest.”

“Okay,” I said, walking over to join him on the floor. The combination of Advil and caffeine had finally kicked in—the elephants tromping through my head began to slow down. I took the block from him. “Where do you want me to put it?”

“I’ll do it,” he said, snatching the toy back immediately.

“Okay,” I said, smiling. “Gotcha, boss.” I watched him play for a few minutes, amazed by the intensity of my feelings. No one told me that the love I’d feel for my child would be so pervasive and consuming. Charlie came howling from my body and in an instant, my own soul was woven into his so completely it became impossible to extricate one from the other.

“Here,” my son said again, handing me another red block. He pointed to the top of the tower he had built. “Put it there.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, setting the block where he wanted it. “Like that?”

“Good job, Mama,” he said, patting me on my knee with his plump hand. He suddenly jumped up and launched himself full-force into my lap, pushing me over onto the floor with his arms around my neck.

“Oomph!” I said, laughing and hugging him to me so he wouldn’t crash his head into the nearby bookcase.

“I love you to the stars and back!” he announced.

“All the way to Timbuktu,” I answered.

“All the way to Kalamazoo,” he finished. The words were our nightly routine when I tucked him into bed, what I whispered in his ear before he drifted off to sleep.

Charlie pulled back and landed a wet, slightly open-mouthed kiss on my cheek. His breath smelled faintly of the peanut butter and syrup he had had on his pancakes. I almost wished I could take a bite out of him, I loved him so much.

We played for a couple of hours, coloring and building with more blocks. I took a hot shower, trying to scrub the cobwebs from my brain, while Charlie sat on the bathroom floor, chattering away about Spider-Man and what kind of superhero outfit he wanted me to sew for him.

“Mama doesn’t sew, baby,” I said from behind the shower curtain. Where he had gotten the idea that I could, I had no clue. I opted to throw away his socks rather than darn them; he’d even seen me do it.

“That’s okay,” he said simply. “You can learn.”

We both got dressed, then went outside to the backyard so Charlie could climb on the wooden jungle gym Martin had tried to put together for Charlie’s second birthday party. At the last minute, I ended up having to call the toy store to send an employee to finish the job.

“I can do it, Cadee,” my husband had said.

“Uh-huh. And is it supposed to lean against the fence?” I only meant to tease him, but he dropped his tools to the lawn and stormed off toward the garage.

“It’s a safety thing, honey!” I called out. “We don’t want the other kids’ parents to sue!” He didn’t answer, and every time after that when a project needed to be done around the house and I asked him to help me with it, he’d shake his head and say, “I don’t know, Cadee. You don’t want me to screw it up. Maybe you’d better call a professional.”

Now, the May sun was warm on my face, and my eyes wandered over the overgrown clumps of vibrant bluebells and delicate forget-me-nots along the fence. Yard work—another thing I didn’t have time to do. The outside chores had always been Martin’s. At least, when he came home from work long enough to do them.

“Watch me, Mama!” Charlie said over and over again as he went down the slide or made his way up the ladder. “Watch this!”

“I’m watching,” I reassured him, my arms crossed over my chest. My thoughts danced with the descriptions I needed to be writing. I wished I could just sit Charlie in front of a movie and get started. I knew some writers could get words on the page no matter what was going on around them—with music playing or children chattering in the background—but I wasn’t one of them. I needed silence to work.

I pushed Charlie on the swing and chased him around the moss-covered pear tree until it was time for lunch. “What do you want to eat?” I asked as we walked up the back steps into the house.

“Orange,” Charlie said.

“Oranges?” I said. “I don’t think we have any.”

“No. Not oranges. Orange.”

“Ohhhh,” I said, realizing what he meant. It was his favorite color. I fed him macaroni and cheese and sliced peaches.

After he ate, I snuggled with Charlie on the couch and watched an episode of The Berenstain Bears. As I held him, his eyelids drooped and his breathing deepened. When the show ended, I glanced at the clock. It was almost 1:00.

“Time for your nap, baby,” I said, kissing the top of his head. When he didn’t respond, I knew he was asleep.

I carried him into his room, marveling at the heft of his deadweight, careful to keep jostling his body to a minimum. I lay him down, slipped off his shoes, and tucked his favorite blue blanket up around his neck, making sure the silky edge was against his face, the way he liked it. Quietly, I shut the door behind me, listening for any movement. He didn’t make a sound. Success.

Back in the kitchen, I grabbed a poppy seed muffin I’d baked the day before, thinking it might be better for me than finishing off the entire pot of cheesy pasta. I started to type the description of a popular San Juan Islands, Fidalgo Bay, 1890s Victorian. I was cheating a little, using online reviews for references and interviewing the establishments’ owners over the phone instead of in person, but the logistics of lugging Charlie along for a road trip to visit them all were too complicated to consider.

I’d barely gotten a page completed when I heard Charlie’s door open. His bare feet pattered down the hall.

“You need more sleep, baby,” I said, turning to look at him when he came through the kitchen’s arched doorway.

“Nope!” he said cheerfully, though his cheeks were rosy and his eyes half-lidded. “I’m hungry.”

“You just ate lunch. And you only rested half an hour. You need to get back in bed. Mama needs to get some work done.”

He clambered up into a chair and looked at me expectantly. “I’ll help you.”

I sighed, tapping my fingers on the top of my thigh. “No, honey. You can’t. This is grown-up work.”

He pounded on the table with his fists. “I’ll help you!”

“Charlie,” I said as gently as possible. “You can play quietly in your room, but Mama needs to be by herself for a little while. We’ll play later.” If he didn’t get a nap, I wouldn’t get anything accomplished and both of us would hate the rest of this day.

“No!” Charlie said, setting his jaw in a determined line. It was his father’s expression, one I had seen on my ex-husband’s face too many times to count.

Something in me snapped. I shoved my chair back from the table, then tucked my hands in my son’s armpits and lifted him out of his chair. He gave a few rowdy kicks and managed to knock my laptop onto the floor with his foot. It landed on the checkered linoleum with a frightening clatter. All my work was on that computer—I wasn’t a master of backing up my copy. If he just killed the machine, I was screwed.

“Dammit, Charlie!” I yelled. My heartbeat galloped in my throat. “Knock it off.”

“Don’t say ‘dammit’!” he screamed, continuing to struggle as I carried him back down the hall to his room.

“You’re fine,” I told him through gritted teeth. “Mama’s here. You’re fine. “

“Daddy!” he wailed, wriggling and writhing to get away from me. “I want my daddy!”

It made me crazy how often my son asked for Martin. Charlie and I spent most of our time alone even when his father lived with us. Yet something did shift when my husband no longer came home at night. I was it. Responsible for absolutely everything. Sometimes I wasn’t sure I was up for the job.

I lay Charlie in his bed. “I love you, sweetie, but you need to take a rest.” I kept my voice calm, though aggravation skittered along its edges. I smoothed his hair and he kicked at the wall, still crying. I hoped he’d tire himself out and go back to sleep as he’d done a hundred times before. I closed the door behind me again and this time, I stood in the hall, waiting.

Over the next five minutes his screaming intensified. There was the loud thunk of something being thrown against his door. A toy, probably. It wouldn’t be the first time. The tips of my nerves burned beneath my skin.

“You’re a bad mama!” he yelled.

His words felt like a slap. He’s only three. He doesn’t mean it. Tantrums are normal for lots of kids. Still, tears rose in my eyes and I pressed a curled fist against my mouth at hearing my child accuse me of my deepest fear.

Swallowing the lump in my throat, I returned to the kitchen and picked up my laptop, happy to see it wasn’t destroyed. I would never get anything done with him screaming in the background; I needed someone to watch him. I thought about calling my younger sister, Jessica, but she was seven months pregnant with twins so I didn’t want to bother her. My mother was more the type to visit her grandchild than to babysit him, so with this late notice, that left me with only one option.

I grabbed my cell phone and punched in Martin’s number, taking a few deep breaths as I always needed to before talking with him.

“I’m really sorry to bug you,” I began, hoping he’d give me a different answer than the one I expected. “But can you take Charlie for a few hours this afternoon? I’m on deadline.”

“Why’s he screaming?” Martin asked.

I gave him the short version of why his child was pitching a fit. “I know it’s my weekend, but if you can help me out, I’d really owe you one.”

“Sorry, I would, but I’ve already got plans,” he said.

You always have plans, I wanted to say, but managed to bite my tongue. The role of bitter divorcée was one I worked hard to avoid.

“I can take him an extra night this week, though,” he went on to offer.

“The article’s due tomorrow,” I said, trying to keep the desperation out of my voice. The editor had already cut me some slack; it was unlikely he would do it again.

Martin sighed. “I don’t know what to tell you, Cadee. I can’t do it. But I’ll pick him up Wednesday at five.”

After he hung up, I slammed down the phone on the table, adrenaline pumping through my veins. Goddamn him. So much for the concept of coparenting. I shouldn’t have bothered to call. Charlie’s cries escalated into punctuated, high-pitched shrieking. I didn’t know what to do. I started to weep, the internal barricade I usually kept high and strong crumpling beneath the weight of my frustration.

After a few minutes of feeling sorry for myself and wondering how my child didn’t sprain his vocal cords screeching like he was, I plunked back down at the table, wiping my eyes with my sleeve and thinking I might just polish off that pot of pasta after all. As my gaze traveled toward the stove, the sunlight streaming in through the window glinted off a bottle of merlot on the counter and caught my eye.

I checked the clock. It was almost 2:00. People who worked outside the home had drinks with a late lunch, didn’t they? I could have half a glass now, just to take the edge off, and maybe another before bed. Not even two full glasses for the day. Some people drank more than that with their dinner alone. And it wasn’t like I did it all the time. I needed to relax. Just this once, I thought as my son sobbed himself to sleep in his room. Just today.

I swore to myself I’d never do it again.

Pulling up in front of Alice’s house to pick up Charlie, the shame is strong enough in me that I must fight the urge to drive away. I’d go anywhere to not feel this. Canada is only a couple of hours north. I could run off and not have to deal with any of it. I could start again, build a new life with our maple syrup-friendly neighbors. I could learn to say “eh?” at the end of every sentence. I could blend right in. I wouldn’t have to go to treatment. I wouldn’t have to write all those silly assignments or attend AA meetings. I wouldn’t need to find some ridiculous notion of a higher power. I could leave. I could . . .

There he is. All thoughts of escape disappear. Charlie comes bounding out of my ex-mother-in-law’s front door, his dark brown curls bouncing around his perfect, elfin face. He needs a haircut, I note. Something for us to do today, something to fill the hours we are alone. He is wearing blue jeans and a polo shirt I didn’t buy for him, one I would have left on the rack at the store. His smile is wide. His hands flutter in excitement as he races down the stairs toward me.

“Mommy!” he exclaims, and my heart melts into liquid. I throw the gearshift into park, turn off the engine, and jump out to meet him. He leaps into my open arms and clings to me like a spider monkey, his skinny arms and legs wrap around my neck and waist in a viselike grip. I bury my nose in his neck and breathe him in—his nutty, warm, slightly funky little-boy scent. This is the first time in two months that we’ll be alone overnight. Two months and four days since Martin came to my house and took him away.

“Where were you?” he demands. “I missed you!”

“I’ve missed you, too, butternut,” I say, choking on my tears. I nibble on the thin skin of his neck, growling playfully. It is our game.

“Ahhhh! Stop it!” he squeals.

I nibble again. My lips cover my teeth so I don’t accidentally hurt him. He squeals again and wriggles like an eel in my arms. “Let me go!”

“No, I won’t let you go! No way!” I say, holding his precious body to mine.

“Mama! Ahhh!! It tickles!!” His sturdy legs wrap themselves even tighter around me and he continues to squirm.

God, oh God, how could I ever have done anything to lose him? How could I have been drunk around this gorgeous little boy? I am sick—undeniably ill.

“Hello, Cadence.” My ex-mother-in-law’s words land like a gauntlet at my feet. They cause me to peek up from the warmth of my son’s neck. Alice stands atop her front steps, arms folded tightly across her chest. Her eyes are stone. Her silver-streaked black hair is pulled back from her face in a tight bun at the base of her neck, not a loose strand in sight. She has applied just enough makeup to avoid being mistaken for dead. She wears her standard khaki slacks and practical, scoop-neck, long-sleeved navy knit top. No frills for this woman. No fussy, floral prints. She is all business, the bare necessities.

“Kill her with kindness,” Andi said when I expressed my anxiety about having to see Alice in this first official exchange. “That’ll piss her off. “

“Really?” I asked, skeptical. “I want to piss her off?”

“No, you want to be kind.” She gave me a beatific smile. “The pissing her off part is just a bonus.”

Purely out of respect for Andi’s advice, I manage to smile at Alice when she greets me. It is a tenuous, struggling movement—my cheeks literally tremble with the effort. “Hi, Alice. How are you?”

“Fine.” She gives me a tight-lipped look, one I recognize as her version of a smile under duress. From the moment I met her, it was clear that Alice had envisioned a much more suitable partner for her only child. A lithe, Nordic blond perhaps, petite and demure. Instead, she got me—all wild brown curls and fleshy curves. Big breasts, big opinions.

“You’re late,” she says.

I twist my wrist up from my son’s body, which is still clamped around me, and look at my watch. Ten minutes after 9:00 a.m. Panic seizes me. She’ll report me to Mr. Hines, the court guardian. I’ll lose my son. I worry that everything I do goes under automatic scrutiny. How does it look for me to do this? I wonder, as I order a soda at dinner. Are they wondering why I don’t ask for a real drink? A glass of wine? A vodka tonic with a twist? I feel like I have to explain every little movement, or lack of movement.

It’s similar to how I used to feel when I’d buy wine at a different grocery store or corner market every day. “I’m having a party tonight,” I’d explain to an uninterested checker. “Eight people, so I’ll need four bottles of wine.” Like the checker gave a good goddamn.

“Only a few minutes late,” I say to Alice now, not just a little defensively. “Sorry.”

“It’s fine,” Alice says, looking at me with cool disdain.

Charlie chooses this moment to wriggle out of my grasp. He jumps up and down in front of me. “Look, Mama! I can do a cartwheel!” Falling forward, he places both palms flat on the wet grass and does a donkey kick not more than eight inches or so off the ground. He lands on his knees with a thump.

I clap for him. “Excellent!” He grins, causing the deep, cherry-pit dimple on his left cheek to appear.

“Charles!” Alice scolds. “Look what you did to your jeans!”

The grin vanishes. He stands, looks down at his now brightly stained green knees. “Sorry.”

I reach down, ruffle his curls. “That’s okay, buddy. That’s why God invented Spray ’n Wash, right?”

“Yeah!” he says. He looks up at me, smiling again, and then to the sky. He waves. “Thanks, God!”

Oh, my Charlie. My eyes well up. Would you look at that. Look at that sweet soul. I haven’t completely screwed him up.

“God isn’t doing your laundry,” Alice says lightly as she steps down the stairs.

I look at her, anger tight and warm in my chest. It’s that mama bear feeling rearing its head.

She sees my eyes flash. Her expression melts into one of supreme smugness. That’s right, it says. Here it comes. Yell at me. Give me something to tell the court.

Kill her with kindness. The chant I played over and over in my head on the way to this moment. I take a deep breath before speaking.

“Thanks for taking such good care of his clothes. I’ll wash his jeans today, and bring them back.” And then, because I cannot help it, I continue. “Why doesn’t Martin do his laundry?”

She lifts her jaw. “Martin is busy working. Martin is busy making sure his son is fed and clothed and brought to school on time. He is very busy being a parent.”

Which is more than I can say about you, I hear the unspoken finish to her statement. She doesn’t need to speak. Her eyes paint the words: black, ugly brushstrokes in the air between us.

“How nice for him,” I spit out. I can’t stop myself. “Most single parents don’t have someone to pick up their slack.” Dammit. And I was doing so well.

“Most single parents don’t drink themselves into oblivion, either,” she launches back. She speaks quietly, over Charlie’s listening ears. “I didn’t.”

Her words pummel me. They stop my breath. Sudden, violent guilt invades each cell in my body. She is sacred and pure. I am the evil, rotten mother who couldn’t control her drinking. I deserve her hatred. I deserve the pain that goes with it. She is right and I am wrong. I earned every minute of all I have to endure.

Charlie grabs my arm with both hands and pulls in the direction of my car. “Mama, let’s go,” he whimpers. “I want to go.”

“Okay, monkey,” I say. And then, to Alice, “I’ll have him back tomorrow at twelve o’clock.”

“Twelve o’clock sharp,” she says.

“Right,” I say. “C’mon, Mr. Man.” Any fight I had is knocked clear out of me. Round one: Alice. I let Charlie lead me to the car and help him climb into his booster seat, ever conscious of Alice’s sharp blue eyes on me. For good measure, I say loudly, “All right, you’re all buckled in,” just so she can’t tell the court I let Charlie bounce around like a red rubber ball inside my car. Anything is a threat now. Anything could be used against me. I step slowly around to the driver’s side, open my door, and then force myself again to smile at Alice and wave good-bye. “Say ’bye to your omi, Charlie bear.” This is what he calls her, Omi—the German equivalent of Nana.

“’Bye, Omi!” he chimes in. This is out of good breeding alone, I convince myself. Good breeding that I, as his mother, am personally responsible for.

I buckle my own seat belt, start the car, and look at my son in the rearview mirror. “Ready, Spaghetti Freddie?” I ask.

“Ready!” he squeals. He kicks his feet against the seat in front of him in emphasis.

I pull away from the curb, wondering if the real question is, how ready am I?

Being drunk in front of your child is right up there on the Big Bad No-no List of Motherhood. I knew what I was doing was wrong. I knew it with every glass, every swallow, every empty bottle thrown into the recycle bin. I hated drinking. I hated it . . . and I couldn’t stop. The anesthetic effect of alcohol ran thick in my blood; the Great Barrier Reef built between me and my feelings. I watched myself do it in an out-of-body experience: Oh, isn’t this interesting? Look at me, the sloppy drunk. It snuck up on me, every time. It took me by surprise.

I tried to stop. Of course I tried. I went a day, maybe two, before the urge burned strong enough, it rose in my throat like a gnarled hand reaching for a drink. My body ached. My brain sloshed against the inside of my skull. The more I loathed drinking, the more I needed it to find that sweet spot between awareness and agony. Even now, even though it has been sixty-four days since I have taken a drink, the shame clings to me. It sickens my senses worse than any hangover I’ve ever suffered.

It’s early April, and I drive down a street lined with tall, sturdy maples. Gauzelike clouds stretch across the icy blue sky. A few earnest men stand in front of their houses appraising the state of their lawns. My own yard went to hell while I was away and I have not found time nor inclination to be its savior.

Any other day I would have found this morning beautiful. Any other day I might have stopped to stare at the sky, to enjoy the fragile warmth of the sun on my skin. Today is not any other day. Today marks two months and four days since I have seen my son. Each corner I turn takes me closer and closer to picking him up from his grandmother’s house. For now, it was decided this arrangement was better than my coming face-to-face with Martin, his father.

“What do they think will happen?” I’d asked my treatment counselor, Andi, when the rules of visitation came down. My voice was barely above a whisper. “What do they think I’d do?”

“Think of how many times you were drunk around Charlie,” she said. “There’s reason for concern.”

I sat a moment, contemplating this dangerous little bomb, vacillating between an attempt to absorb the truth behind her words and the desire to find a way to hide from it. I kept my eyes on the floor, too afraid of what I’d see if I looked into hers. Two weeks in the psych ward rendered me incapable of pulling off my usually dazzling impersonation of a happy, successful, single mother. Andi knew I was drunk in front of Charlie every day for over a year. She’d heard me describe the misery etched across my child’s face each time I pulled the cork on yet another bottle of wine. She knew the damage I’d done.

“Cadence?” she prodded.

Finally, I managed to look up at her round, pretty face. For the most part, I like Andi, except when she suggests I might be wrong about something. In the two months I have known her, this has happened more often than I’d like.

She met my gaze and smiled softly. I didn’t respond, so she spoke again. “Try to think about it as what’s best for Charlie.”

“Isn’t it best for Charlie to see his parents get along?” I asked. I’ve read enough advice books on how divorced parents should act in front of their children to feel pretty confident I was right about this one. I longed to stand before Martin and put on the face that said everything was okay. I wanted to prove to him that whatever darkness had reared its ugly head inside me had subsided; I had it back under control.

“Yes, seeing you getting along would be best,” Andi conceded. “But it’s not realistic. Martin just filed to take custody away from you. Your emotions are running insanely high. Even with the best intentions it would be hard not to confront him.”

“I don’t want to confront Martin,” I said. “I just want to talk to him. Explain that I’m better. That I’m getting help with this . . . problem.”

“Pleading your case is just going to stir up a bunch of negativity. Charlie is five years old. Even if you manage to restrain yourself from fighting, he’s smart enough to pick up on facial expressions and the tone of your voices. You don’t want to upset him.”

“I could fake it,” I said. I knew it wouldn’t take much. When we were married, Martin and I fought and then went to bed with an invisible force field between us. In the morning, I gave him a smile, a kiss, and then made a pot of coffee and his lunch. Shape-shifting into what made Martin happy was something I already knew how to do.

Andi looked at me with her gentle, tigerlike topaz eyes. “Have you considered that maybe ‘faking it’ is what got you here?”

I was eight months pregnant when Martin and I decided I would leave my reporting job at the Seattle Herald. I’m not sure where I got the idea that working from home while taking care of an infant would be easy; I guess I thought freelance writing would grant me flexibility and plenty of free time to be with my son. Of course, after spending three years juggling the incessant demands of both self-employment and motherhood, I realized there was nothing easy about it. There was one person in charge of my day, and his name was Charlie.

“Mama!” he said, jumping on my bed one morning in May, a few months before he turned four. “Time to wake up!”

I groaned, rolled over beneath the covers, and peeked at the clock. Six o’clock on a Sunday. Oh, sweet Jesus. “Charlie, honey, can you go back to bed? It’s too early.”

“No, it’s not!” He bounced on the mattress, jarring my throbbing head. Finishing off that bottle of merlot had been a bad idea. Since Martin moved out the previous November, my usual limit was one glass, maybe two a night, and then it was only to help me sleep. But then the night before, with Charlie already down for the count, I figured it wouldn’t hurt to enjoy another glass while I worked. When the contents of my cup grew low, I splashed in a little more to top it off. Before I knew it, there was none left to pour.

Now, I propped myself up on my elbows and looked at my son through scratchy, dry eyes. He was starting to lose his babyish looks—his dark, wispy curls were mussed, his cheeks were pink, and his ears stuck out from his head like a chimpanzee’s. My little monkey.

“Do you want to cuddle with me for a while?” I asked, hoping he’d take the bait.

“No!” Charlie said. “I want pancakes. And yogurt.”

I flopped back down and threw my forearm over my eyes, causing the pain to ricochet like a bullet beneath my skull. If I didn’t do something for this headache soon, it would take over and I’d never get anything written today. I had barely started my article on the Northwest’s Top Ten Bed-and-Breakfasts for Seattle magazine, and while it was originally due the week before, I managed to sweet-talk the editor into extending my deadline through tomorrow. I couldn’t afford to screw up and not get paid.

Charlie pushed me playfully and giggled. He was not going to give up.

I sighed and forced myself to rotate up and out of bed. The room spun around me, so I kept my eyes closed and took deep breaths until it passed. Ugh. I felt awful. I hoped I wouldn’t be sick.

“Pancakes!” Charlie hollered, and I cringed, clutching my forehead with one hand.

“Shh, honey. Mama has a headache.”

He leapt off the bed and sped down the hall in his Spider-Man pajamas. The noisy clamor of cartoons quickly echoed throughout the house.

I trodded after him, my bare feet slapping against the hardwood floors. I wondered when I had changed out of my jeans and into my pajamas the night before; I didn’t remember doing it. I must have been really tired, I thought hazily. I’m really not getting enough sleep.

In my tiny, black-and-white, fifties-style kitchen, I immediately went for the super-size bottle of Advil on the counter and shook four out into my hand. I popped them into my mouth and used my cupped palm beneath the faucet to splash them down with a water chaser.

I fought with the coffee filters for a minute, but soon managed to get a pot brewing, throwing in an extra scoop of aromatic grounds for a super-charged medicinal kick of caffeine. Charlie raced in from the living room and threw his arms around my legs, squeezing them tightly.

“I love you, Mama,” he said.

“I love you, too, Charlie bear.” I hoped my voice didn’t sound as weary as I felt. I reached around and cupped my hand against the curve of his head.

He let go of me, padded over to the refrigerator, and grabbed a strawberry yogurt from the bottom shelf. I kept most of his snacks within reach so he could get them himself. I’d read somewhere that giving him tasks like this to accomplish on his own would encourage his self-esteem. It also reduced the number of things I needed to do for him each day from one hundred to ninety-nine.

“Did you turn off the TV?” I asked absentmindedly, then realized the sound of cartoons had ceased.

“Yep!” He sat at the chrome-legged, black Formica kitchen table that put in double duty as my desk. The house was too small for an office, so my laptop and printer took up one end of the table, and at meal time Charlie and I took up the other. It was all the space I needed, really, since most of my work was done online and over the phone.

“Let me get you a spoon,” I said, reaching into the silverware drawer and setting the utensil on the table. “Eating yogurt with your fingers isn’t such a hot idea.”

With an impish grin, he wiggled his fingers threateningly over the open cup.

“Don’t you dare,” I said. Too late. He dropped his fingers in the creamy pink yogurt and scooped a bite into his mouth.

“Charlie,” I said, exasperated. “No.” I snatched a dish towel from the counter, took him by the wrist, and wiped his hand clean. I gave the bottom of his chin a gentle pinch. “Don’t do that again, okay? You’re a big boy. You know better than that.”

“Okay,” he said. He dutifully picked up his spoon and began to eat. My head screamed at me to go back to bed, but I knew it would be impossible.

While I inhaled my coffee from a black, soup bowl-size mug, I zapped a few frozen pancakes in the microwave. When they were done, I cut them up into bite-size squares and served them to my son. I nibbled on one without butter or syrup, hoping the carbs would take the edge off my nausea.

“All done!” Charlie said, pushing away from the table and jumping down from his chair. “Want to come play with me?”

I smiled at him. “I need to work for a little while. Can you watch TV quietly?”

“But I want you to play,” he whined, yanking on my hand.

I took a deep breath, then exhaled. That was that. As always, work would have to wait for his nap time. I knew spending time with my son was more important, but the money I’d received in the divorce settlement wasn’t going to last forever. If I watched my pennies and pulled in at least a little bit from freelancing, it would be enough to live on for a couple of years. Martin paid child support to cover basic things like Charlie’s clothes and food, but in order to survive on my own long term, I needed to step up my professional game. Something that was difficult to do, considering I wasn’t all that crazy about freelance journalism in the first place. After I left the Herald, my career had morphed into a matter of convenience rather than a passionate pursuit, but it was all I knew how to do. So for the time being, I didn’t have a choice but to make it work.

“Mama!” Charlie said, jerking on my hand again. I allowed him to lead me into the living room, a small space made to look even smaller by the arrangement of an overstuffed khaki love seat and two matching, comfy lounge chairs with ottomans. There was a flat-screen television hanging above the river-stone fireplace—an indulgence Martin encouraged before he moved out, a purchase I reluctantly grew to enjoy. The built-in cherry shelves on each side of the fireplace were stuffed with my books, a few candles and pictures, but mostly Charlie’s toys.

He let go of my hand and ran over to the enormous pile of brightly hued Duplo blocks that already lay in the middle of the tan, skeleton leaf-imprinted area rug. He sat down and gave me a toothy grin.

“Here,” Charlie said, holding out a single red block. “This is yours. Mine are the rest.”

“Okay,” I said, walking over to join him on the floor. The combination of Advil and caffeine had finally kicked in—the elephants tromping through my head began to slow down. I took the block from him. “Where do you want me to put it?”

“I’ll do it,” he said, snatching the toy back immediately.

“Okay,” I said, smiling. “Gotcha, boss.” I watched him play for a few minutes, amazed by the intensity of my feelings. No one told me that the love I’d feel for my child would be so pervasive and consuming. Charlie came howling from my body and in an instant, my own soul was woven into his so completely it became impossible to extricate one from the other.

“Here,” my son said again, handing me another red block. He pointed to the top of the tower he had built. “Put it there.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, setting the block where he wanted it. “Like that?”

“Good job, Mama,” he said, patting me on my knee with his plump hand. He suddenly jumped up and launched himself full-force into my lap, pushing me over onto the floor with his arms around my neck.

“Oomph!” I said, laughing and hugging him to me so he wouldn’t crash his head into the nearby bookcase.

“I love you to the stars and back!” he announced.

“All the way to Timbuktu,” I answered.

“All the way to Kalamazoo,” he finished. The words were our nightly routine when I tucked him into bed, what I whispered in his ear before he drifted off to sleep.

Charlie pulled back and landed a wet, slightly open-mouthed kiss on my cheek. His breath smelled faintly of the peanut butter and syrup he had had on his pancakes. I almost wished I could take a bite out of him, I loved him so much.

We played for a couple of hours, coloring and building with more blocks. I took a hot shower, trying to scrub the cobwebs from my brain, while Charlie sat on the bathroom floor, chattering away about Spider-Man and what kind of superhero outfit he wanted me to sew for him.

“Mama doesn’t sew, baby,” I said from behind the shower curtain. Where he had gotten the idea that I could, I had no clue. I opted to throw away his socks rather than darn them; he’d even seen me do it.

“That’s okay,” he said simply. “You can learn.”

We both got dressed, then went outside to the backyard so Charlie could climb on the wooden jungle gym Martin had tried to put together for Charlie’s second birthday party. At the last minute, I ended up having to call the toy store to send an employee to finish the job.

“I can do it, Cadee,” my husband had said.

“Uh-huh. And is it supposed to lean against the fence?” I only meant to tease him, but he dropped his tools to the lawn and stormed off toward the garage.

“It’s a safety thing, honey!” I called out. “We don’t want the other kids’ parents to sue!” He didn’t answer, and every time after that when a project needed to be done around the house and I asked him to help me with it, he’d shake his head and say, “I don’t know, Cadee. You don’t want me to screw it up. Maybe you’d better call a professional.”

Now, the May sun was warm on my face, and my eyes wandered over the overgrown clumps of vibrant bluebells and delicate forget-me-nots along the fence. Yard work—another thing I didn’t have time to do. The outside chores had always been Martin’s. At least, when he came home from work long enough to do them.

“Watch me, Mama!” Charlie said over and over again as he went down the slide or made his way up the ladder. “Watch this!”

“I’m watching,” I reassured him, my arms crossed over my chest. My thoughts danced with the descriptions I needed to be writing. I wished I could just sit Charlie in front of a movie and get started. I knew some writers could get words on the page no matter what was going on around them—with music playing or children chattering in the background—but I wasn’t one of them. I needed silence to work.

I pushed Charlie on the swing and chased him around the moss-covered pear tree until it was time for lunch. “What do you want to eat?” I asked as we walked up the back steps into the house.

“Orange,” Charlie said.

“Oranges?” I said. “I don’t think we have any.”

“No. Not oranges. Orange.”

“Ohhhh,” I said, realizing what he meant. It was his favorite color. I fed him macaroni and cheese and sliced peaches.

After he ate, I snuggled with Charlie on the couch and watched an episode of The Berenstain Bears. As I held him, his eyelids drooped and his breathing deepened. When the show ended, I glanced at the clock. It was almost 1:00.

“Time for your nap, baby,” I said, kissing the top of his head. When he didn’t respond, I knew he was asleep.

I carried him into his room, marveling at the heft of his deadweight, careful to keep jostling his body to a minimum. I lay him down, slipped off his shoes, and tucked his favorite blue blanket up around his neck, making sure the silky edge was against his face, the way he liked it. Quietly, I shut the door behind me, listening for any movement. He didn’t make a sound. Success.

Back in the kitchen, I grabbed a poppy seed muffin I’d baked the day before, thinking it might be better for me than finishing off the entire pot of cheesy pasta. I started to type the description of a popular San Juan Islands, Fidalgo Bay, 1890s Victorian. I was cheating a little, using online reviews for references and interviewing the establishments’ owners over the phone instead of in person, but the logistics of lugging Charlie along for a road trip to visit them all were too complicated to consider.

I’d barely gotten a page completed when I heard Charlie’s door open. His bare feet pattered down the hall.

“You need more sleep, baby,” I said, turning to look at him when he came through the kitchen’s arched doorway.

“Nope!” he said cheerfully, though his cheeks were rosy and his eyes half-lidded. “I’m hungry.”

“You just ate lunch. And you only rested half an hour. You need to get back in bed. Mama needs to get some work done.”

He clambered up into a chair and looked at me expectantly. “I’ll help you.”

I sighed, tapping my fingers on the top of my thigh. “No, honey. You can’t. This is grown-up work.”

He pounded on the table with his fists. “I’ll help you!”

“Charlie,” I said as gently as possible. “You can play quietly in your room, but Mama needs to be by herself for a little while. We’ll play later.” If he didn’t get a nap, I wouldn’t get anything accomplished and both of us would hate the rest of this day.

“No!” Charlie said, setting his jaw in a determined line. It was his father’s expression, one I had seen on my ex-husband’s face too many times to count.

Something in me snapped. I shoved my chair back from the table, then tucked my hands in my son’s armpits and lifted him out of his chair. He gave a few rowdy kicks and managed to knock my laptop onto the floor with his foot. It landed on the checkered linoleum with a frightening clatter. All my work was on that computer—I wasn’t a master of backing up my copy. If he just killed the machine, I was screwed.

“Dammit, Charlie!” I yelled. My heartbeat galloped in my throat. “Knock it off.”

“Don’t say ‘dammit’!” he screamed, continuing to struggle as I carried him back down the hall to his room.

“You’re fine,” I told him through gritted teeth. “Mama’s here. You’re fine. “

“Daddy!” he wailed, wriggling and writhing to get away from me. “I want my daddy!”

It made me crazy how often my son asked for Martin. Charlie and I spent most of our time alone even when his father lived with us. Yet something did shift when my husband no longer came home at night. I was it. Responsible for absolutely everything. Sometimes I wasn’t sure I was up for the job.

I lay Charlie in his bed. “I love you, sweetie, but you need to take a rest.” I kept my voice calm, though aggravation skittered along its edges. I smoothed his hair and he kicked at the wall, still crying. I hoped he’d tire himself out and go back to sleep as he’d done a hundred times before. I closed the door behind me again and this time, I stood in the hall, waiting.

Over the next five minutes his screaming intensified. There was the loud thunk of something being thrown against his door. A toy, probably. It wouldn’t be the first time. The tips of my nerves burned beneath my skin.

“You’re a bad mama!” he yelled.

His words felt like a slap. He’s only three. He doesn’t mean it. Tantrums are normal for lots of kids. Still, tears rose in my eyes and I pressed a curled fist against my mouth at hearing my child accuse me of my deepest fear.

Swallowing the lump in my throat, I returned to the kitchen and picked up my laptop, happy to see it wasn’t destroyed. I would never get anything done with him screaming in the background; I needed someone to watch him. I thought about calling my younger sister, Jessica, but she was seven months pregnant with twins so I didn’t want to bother her. My mother was more the type to visit her grandchild than to babysit him, so with this late notice, that left me with only one option.

I grabbed my cell phone and punched in Martin’s number, taking a few deep breaths as I always needed to before talking with him.

“I’m really sorry to bug you,” I began, hoping he’d give me a different answer than the one I expected. “But can you take Charlie for a few hours this afternoon? I’m on deadline.”

“Why’s he screaming?” Martin asked.

I gave him the short version of why his child was pitching a fit. “I know it’s my weekend, but if you can help me out, I’d really owe you one.”

“Sorry, I would, but I’ve already got plans,” he said.

You always have plans, I wanted to say, but managed to bite my tongue. The role of bitter divorcée was one I worked hard to avoid.

“I can take him an extra night this week, though,” he went on to offer.

“The article’s due tomorrow,” I said, trying to keep the desperation out of my voice. The editor had already cut me some slack; it was unlikely he would do it again.

Martin sighed. “I don’t know what to tell you, Cadee. I can’t do it. But I’ll pick him up Wednesday at five.”

After he hung up, I slammed down the phone on the table, adrenaline pumping through my veins. Goddamn him. So much for the concept of coparenting. I shouldn’t have bothered to call. Charlie’s cries escalated into punctuated, high-pitched shrieking. I didn’t know what to do. I started to weep, the internal barricade I usually kept high and strong crumpling beneath the weight of my frustration.

After a few minutes of feeling sorry for myself and wondering how my child didn’t sprain his vocal cords screeching like he was, I plunked back down at the table, wiping my eyes with my sleeve and thinking I might just polish off that pot of pasta after all. As my gaze traveled toward the stove, the sunlight streaming in through the window glinted off a bottle of merlot on the counter and caught my eye.

I checked the clock. It was almost 2:00. People who worked outside the home had drinks with a late lunch, didn’t they? I could have half a glass now, just to take the edge off, and maybe another before bed. Not even two full glasses for the day. Some people drank more than that with their dinner alone. And it wasn’t like I did it all the time. I needed to relax. Just this once, I thought as my son sobbed himself to sleep in his room. Just today.

I swore to myself I’d never do it again.

Pulling up in front of Alice’s house to pick up Charlie, the shame is strong enough in me that I must fight the urge to drive away. I’d go anywhere to not feel this. Canada is only a couple of hours north. I could run off and not have to deal with any of it. I could start again, build a new life with our maple syrup-friendly neighbors. I could learn to say “eh?” at the end of every sentence. I could blend right in. I wouldn’t have to go to treatment. I wouldn’t have to write all those silly assignments or attend AA meetings. I wouldn’t need to find some ridiculous notion of a higher power. I could leave. I could . . .

There he is. All thoughts of escape disappear. Charlie comes bounding out of my ex-mother-in-law’s front door, his dark brown curls bouncing around his perfect, elfin face. He needs a haircut, I note. Something for us to do today, something to fill the hours we are alone. He is wearing blue jeans and a polo shirt I didn’t buy for him, one I would have left on the rack at the store. His smile is wide. His hands flutter in excitement as he races down the stairs toward me.

“Mommy!” he exclaims, and my heart melts into liquid. I throw the gearshift into park, turn off the engine, and jump out to meet him. He leaps into my open arms and clings to me like a spider monkey, his skinny arms and legs wrap around my neck and waist in a viselike grip. I bury my nose in his neck and breathe him in—his nutty, warm, slightly funky little-boy scent. This is the first time in two months that we’ll be alone overnight. Two months and four days since Martin came to my house and took him away.

“Where were you?” he demands. “I missed you!”

“I’ve missed you, too, butternut,” I say, choking on my tears. I nibble on the thin skin of his neck, growling playfully. It is our game.

“Ahhhh! Stop it!” he squeals.

I nibble again. My lips cover my teeth so I don’t accidentally hurt him. He squeals again and wriggles like an eel in my arms. “Let me go!”

“No, I won’t let you go! No way!” I say, holding his precious body to mine.

“Mama! Ahhh!! It tickles!!” His sturdy legs wrap themselves even tighter around me and he continues to squirm.

God, oh God, how could I ever have done anything to lose him? How could I have been drunk around this gorgeous little boy? I am sick—undeniably ill.

“Hello, Cadence.” My ex-mother-in-law’s words land like a gauntlet at my feet. They cause me to peek up from the warmth of my son’s neck. Alice stands atop her front steps, arms folded tightly across her chest. Her eyes are stone. Her silver-streaked black hair is pulled back from her face in a tight bun at the base of her neck, not a loose strand in sight. She has applied just enough makeup to avoid being mistaken for dead. She wears her standard khaki slacks and practical, scoop-neck, long-sleeved navy knit top. No frills for this woman. No fussy, floral prints. She is all business, the bare necessities.

“Kill her with kindness,” Andi said when I expressed my anxiety about having to see Alice in this first official exchange. “That’ll piss her off. “

“Really?” I asked, skeptical. “I want to piss her off?”

“No, you want to be kind.” She gave me a beatific smile. “The pissing her off part is just a bonus.”

Purely out of respect for Andi’s advice, I manage to smile at Alice when she greets me. It is a tenuous, struggling movement—my cheeks literally tremble with the effort. “Hi, Alice. How are you?”

“Fine.” She gives me a tight-lipped look, one I recognize as her version of a smile under duress. From the moment I met her, it was clear that Alice had envisioned a much more suitable partner for her only child. A lithe, Nordic blond perhaps, petite and demure. Instead, she got me—all wild brown curls and fleshy curves. Big breasts, big opinions.

“You’re late,” she says.

I twist my wrist up from my son’s body, which is still clamped around me, and look at my watch. Ten minutes after 9:00 a.m. Panic seizes me. She’ll report me to Mr. Hines, the court guardian. I’ll lose my son. I worry that everything I do goes under automatic scrutiny. How does it look for me to do this? I wonder, as I order a soda at dinner. Are they wondering why I don’t ask for a real drink? A glass of wine? A vodka tonic with a twist? I feel like I have to explain every little movement, or lack of movement.

It’s similar to how I used to feel when I’d buy wine at a different grocery store or corner market every day. “I’m having a party tonight,” I’d explain to an uninterested checker. “Eight people, so I’ll need four bottles of wine.” Like the checker gave a good goddamn.

“Only a few minutes late,” I say to Alice now, not just a little defensively. “Sorry.”

“It’s fine,” Alice says, looking at me with cool disdain.

Charlie chooses this moment to wriggle out of my grasp. He jumps up and down in front of me. “Look, Mama! I can do a cartwheel!” Falling forward, he places both palms flat on the wet grass and does a donkey kick not more than eight inches or so off the ground. He lands on his knees with a thump.

I clap for him. “Excellent!” He grins, causing the deep, cherry-pit dimple on his left cheek to appear.

“Charles!” Alice scolds. “Look what you did to your jeans!”

The grin vanishes. He stands, looks down at his now brightly stained green knees. “Sorry.”

I reach down, ruffle his curls. “That’s okay, buddy. That’s why God invented Spray ’n Wash, right?”

“Yeah!” he says. He looks up at me, smiling again, and then to the sky. He waves. “Thanks, God!”

Oh, my Charlie. My eyes well up. Would you look at that. Look at that sweet soul. I haven’t completely screwed him up.

“God isn’t doing your laundry,” Alice says lightly as she steps down the stairs.

I look at her, anger tight and warm in my chest. It’s that mama bear feeling rearing its head.

She sees my eyes flash. Her expression melts into one of supreme smugness. That’s right, it says. Here it comes. Yell at me. Give me something to tell the court.

Kill her with kindness. The chant I played over and over in my head on the way to this moment. I take a deep breath before speaking.

“Thanks for taking such good care of his clothes. I’ll wash his jeans today, and bring them back.” And then, because I cannot help it, I continue. “Why doesn’t Martin do his laundry?”

She lifts her jaw. “Martin is busy working. Martin is busy making sure his son is fed and clothed and brought to school on time. He is very busy being a parent.”

Which is more than I can say about you, I hear the unspoken finish to her statement. She doesn’t need to speak. Her eyes paint the words: black, ugly brushstrokes in the air between us.

“How nice for him,” I spit out. I can’t stop myself. “Most single parents don’t have someone to pick up their slack.” Dammit. And I was doing so well.

“Most single parents don’t drink themselves into oblivion, either,” she launches back. She speaks quietly, over Charlie’s listening ears. “I didn’t.”

Her words pummel me. They stop my breath. Sudden, violent guilt invades each cell in my body. She is sacred and pure. I am the evil, rotten mother who couldn’t control her drinking. I deserve her hatred. I deserve the pain that goes with it. She is right and I am wrong. I earned every minute of all I have to endure.

Charlie grabs my arm with both hands and pulls in the direction of my car. “Mama, let’s go,” he whimpers. “I want to go.”

“Okay, monkey,” I say. And then, to Alice, “I’ll have him back tomorrow at twelve o’clock.”

“Twelve o’clock sharp,” she says.

“Right,” I say. “C’mon, Mr. Man.” Any fight I had is knocked clear out of me. Round one: Alice. I let Charlie lead me to the car and help him climb into his booster seat, ever conscious of Alice’s sharp blue eyes on me. For good measure, I say loudly, “All right, you’re all buckled in,” just so she can’t tell the court I let Charlie bounce around like a red rubber ball inside my car. Anything is a threat now. Anything could be used against me. I step slowly around to the driver’s side, open my door, and then force myself again to smile at Alice and wave good-bye. “Say ’bye to your omi, Charlie bear.” This is what he calls her, Omi—the German equivalent of Nana.

“’Bye, Omi!” he chimes in. This is out of good breeding alone, I convince myself. Good breeding that I, as his mother, am personally responsible for.

I buckle my own seat belt, start the car, and look at my son in the rearview mirror. “Ready, Spaghetti Freddie?” I ask.

“Ready!” he squeals. He kicks his feet against the seat in front of him in emphasis.

I pull away from the curb, wondering if the real question is, how ready am I?

Reading Group Guide

This reading group guide for Best Kept Secret includes discussion questions, ideas for enhancing your book club, and a Q&A with author Amy Hatvany. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book.

Questions& Topics for Discussion

Enhance Your Book Club

A Conversation with Amy Hatvany

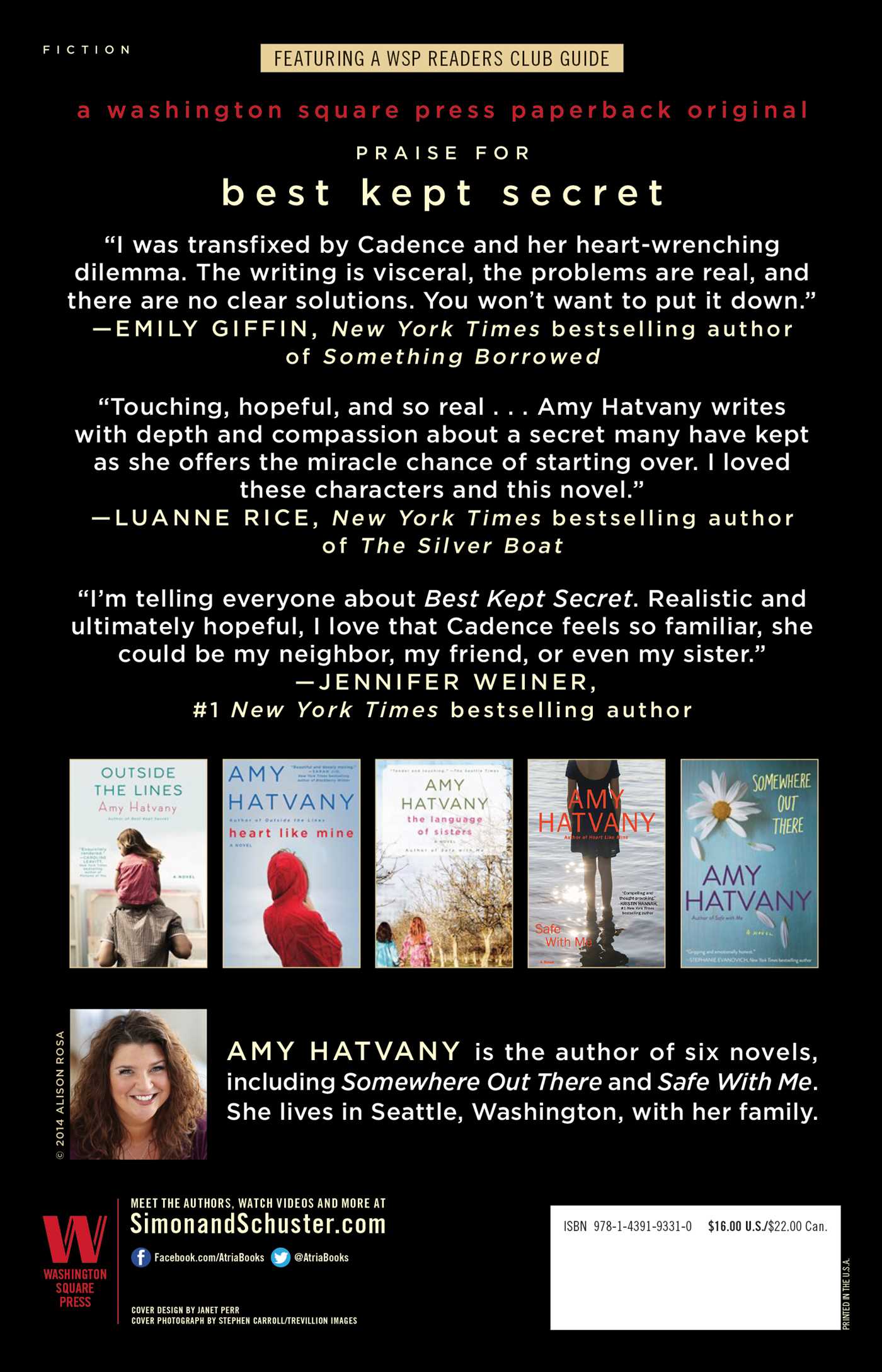

What inspired you to write Best Kept Secret?

I began writing the story as a direct result of my own emotional experiences around being a mother and a recovering alcoholic. While the characters and plot are fiction, Cadence’s emotional turmoil during her descent into addiction and her journey back to sobriety are largely based on what I went through. As I worked on the emotional side of getting sober, it became clear to me that there is a special, intense kind of shame that accompanies being a woman who has been drunk in front of her children. It’s that shame which forces so many of us to keep our addiction secret, for fear of what might happen if we tell someone the truth. We’re terrified of the stigma and possible consequences, but keeping this secret can have devastating—even deadly—results.

I wanted to write a story that would hopefully illuminate how this can happen to anyone. How quickly a seemingly innocent behavior can destroy an otherwise successful, strong woman while she attempts to keep the balls in her life in the air so no one will suspect what’s really going on. I wanted to emphasize how many women, whether or not they end up becoming alcoholic, face incredible amounts of pressure to do everything in their lives perfectly. And when we fail, we experience such profound levels of shame and self-loathing, even as we smile brightly and tell ourselves that we can’t expect to always be perfect. But deep down, perhaps subconsciously, I think we still believe that we “should” be. So we reach for behaviors that drown our shame out, at least temporarily. And then we become ashamed of the behavior, and a vicious cycle emerges.

When do you find the time to write? Do you have a special workspace, or any writing rituals?

Since I still have a day job, I pretty much fit in writing time wherever I can. Early in the morning, late at night, or on the weekends when the kids are still sleeping. My ritual is to get my butt in the chair and keep it there until I hopefully get at least 2,000 words on the page! I wear my most comfy pajamas so I can sit cross-legged while I try to ignore my two adorable dogs, who constantly pester me for attention. Like Cadence, I need total and complete silence in order to write, but I’m easily distracted—“Oh, look! Shiny things!”— so my husband’s Bose noise-cancelling headphones are one of my favorite accessories.

You’re the author of two other novels (published under the name Amy Yurk). How was writing this novel different than your previous two?

It was different for me in many ways. Because of various circumstances, I hadn’t written anything substantial in more than five years, so I felt pretty rusty and stilted when I started out. Obviously, the emotions behind this story were incredibly personal, more so than with my first two, because in revealing Cadence’s secret I was revealing my own. There were dark memories I had to revisit, and it took some time to build up the courage to get the emotional side of those experiences fully onto the page. I worried about being judged for my alcoholism, but the idea that if I told the truth it might help even one woman who is still suffering alone in silence made it worth the risk of what others might choose to think of me personally.

Since this is admittedly such a personal story for you, why did you choose to write a novel instead of a memoir?

I chose to write a novel primarily because that’s the genre I feel most comfortable working within, but at a deeper level, I also wanted to address broader themes around the pressures women face every day in all our roles: as mothers, as professionals in our chosen careers, and as wives, daughters, and friends. Unfortunately, feelings of not being good enough, self-loathing, shame, and guilt are common to most women in our culture, and it was important to me to speak to all women—not just alcoholics and addicts—about the dangers of letting those emotions get the better of us. Fiction allows me a much wider canvas to explore the complicated issues at play. Part of Cadence’s struggle is that she feels like she can’t measure up to other mothers—that her peers in her Mommy and Me group have it “together” in a way that she does not.

Is this a sentiment you’ve observed in women you know?

Absolutely. Society places an increasing amount of pressure on mothers to maintain ridiculous levels of expertise. We’re supposed to be mindful of every possible effect our actions might have on our children and edit ourselves accordingly. We’re expected to be psychologists, nutritionists, teachers, doctors, and organic farmers, (or, at the very least, shop only at local, sustainable farmers’ markets!) If a mother is thinner or better-dressed, or has taught her three-year old how to ask for juice in Mandarin Chinese, it’s a common reaction for many women to feel somehow “less-than” in that woman’s presence.

I think what’s dangerous about this feeling of inadequacy is that it’s entirely based on our perception of what a woman appears to be on the surface. But the truth is we rarely know what’s really going on behind closed doors. Maybe that thin woman has a terrible eating disorder, or the better-dressed woman has a hidden online-shopping addiction that is about to bankrupt her or end her marriage. And so on. When I find myself feeling unworthy next to a mother who manages to work full-time, runs the PTA, and bakes delectable gluten-free goodies for her children, I remind myself that every one of us is fighting some kind of battle. Everyone suffers. Cadence finds some peace and satisfaction in cooking.

Do you have a similar activity that relaxes you and gives you a sense of fulfillment?

Oh, I’m a total foodie, too! I adore cooking—the creative side, of course, that comes out of whipping up something glorious to put in my mouth, but also the calming, Zen-like effect the process has on me. If you do the right thing in a recipe, you get an expected result. There are very few things in life that predictable, so I find a lot of peace in the kitchen. (And on my couch, watching the Food Network! Ina Garten—the Barefoot Contessa—is my personal culinary hero.) I post some of my favorite recipes on my website and on Face-book, and I always love it when readers send me their favorites, too! At the end of the novel, Cadence notes that “if a father spent as much time with his child as I do with Charlie, if that same father worked and went to school, and still somehow managed to see his child that often, the world would canonize him.”

Do you agree that this double standard exists? Do you think we tend to expect different things from mothers and fathers?

I do see a double standard. As the traditional nurturers, mothers are expected to put their children first, and as the typical primary breadwinner, fathers are expected to put their career first. If a family’s situation differs from these standards, our sense of normality is disrupted, and we’re not quite sure how to respond to the people involved.

This is especially notable in the standard perception that after divorce, children should remain with their mother and the father should have visitation rights. How many men are judged or looked down upon for spending their allotted two weekends a month with their children? People don’t make moral suppositions about his character. They don’t automatically wonder what horrible thing he did to not have primary custody. He’s just doing what fathers should do. If he manages to do more than that, he is lauded as going above and beyond.

Now, put a mother in that same scenario, working hard at her career, paying child support, and spending two weekends a month or more with her children. What is your core emotional reaction? What does it bring up in you? Are you immediately horrified, assuming she must be a druggie or a prostitute not to have been granted custody, or at the very least a selfish or immoral creature? The underlying belief is that in order to be a good mother, at least as society defines it, a woman needs to have her children with her the majority of the time. Mothers without primary custody are typically ostracized.

Some might say these expectations are shifting, but I would argue that overall, they have not. Our culture’s belief systems around gender roles are deeply entrenched, and judgment comes much easier to most of us than acceptance.

When Cadence researches mothers and alcoholism, she comes upon the Whore/Madonna theory of societal expectations for feminine behavior. Can you tell us a bit more about why you chose to mention this in the novel? Do you think that women face more of a stigma with alcoholism than men do?

My decision to include this reference goes back to societal expectations around how women should behave, especially once they become mothers. The idea that a woman should aspire to a sort of self-sacrificing sainthood once she has children is one of the chief obstacles that keeps a woman struggling with addiction from getting the help she needs. Even if she isn’t a mother, the cultural preset notion is that female alcoholics are sexually trashy. Male alcoholics are often seen as sexually indiscriminate, too, but sexual prowess in men is encouraged, if not worshipped in our culture, whether the man is an alcoholic or not. The lens society uses to view women who suffer from alcoholism is a much different prescription than the one used for men.

Our culture is more comfortable with absolutes around sexuality—a woman is either the Madonna or the Whore. This categorization is so ingrained in people’s minds that many aren’t even aware of their own prejudice. And how many women do you know who would step up and admit their problem with alcohol or drugs, knowing this label (drunk = whore) would be applied to them? The fear of this is a significant contributor to why so many women go without the help they need. They’re diagnosed by their doctors as depressed or anxious, and the terror of that damaging stigma keeps them from talking about the real trouble they’re in. Both Laura and Susanne are friends of Cadence’s who struggle with addiction, and both are unable to overcome their reliance on drugs and alcohol.