LIST PRICE $15.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

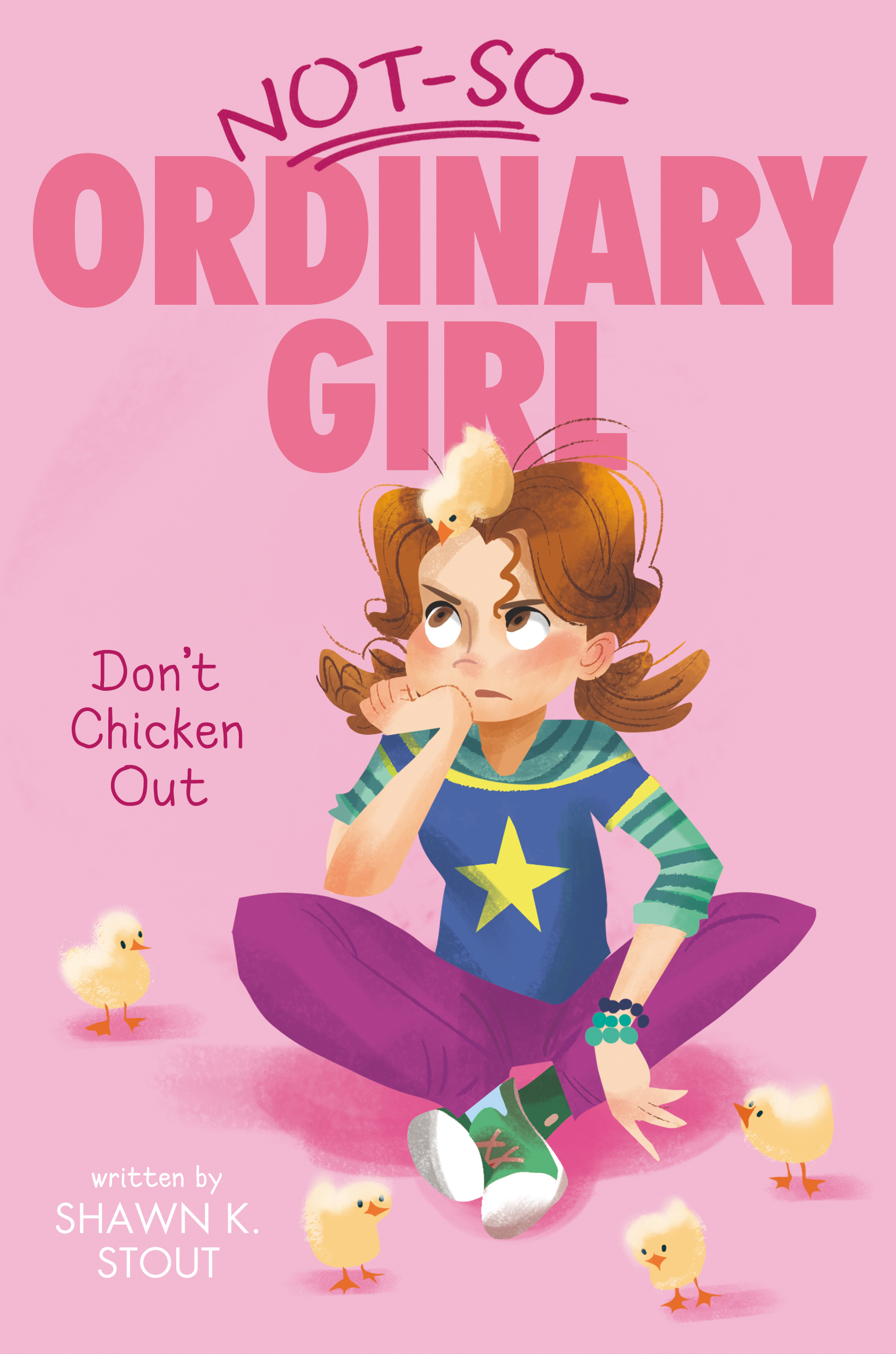

Fiona lands herself in a fairground fluster in this conclusion to the mischievous and charming Not-So-Ordinary Girl trilogy.

Fiona is tired of hearing “no” from everyone. Especially when it is followed by: “You’re not old enough.” Can she go all the way to California by herself to visit her mom? “Not on your life,” says Dad. Can she do something more exciting than handing out maps at the Great Ordinary Fair along with the rest of Mr. Bland’s class? “Not until next year, when you’re in fifth grade,” answers Mr. Bland.

Fiona sets out to prove that she is, in fact, old enough to do things on her own—and ends up babysitting chickens in the fair’s poultry pavilion. It’s not easy being trustworthy and mature, especially when nobody is paying attention. But when the feathers start to fly at the Great Ordinary Fair, Fiona sticks her neck out for a new friend (and a bunch of chickens) and learns a few things about herself and what it means to take responsibility, even when things go really wrong.

Fiona is tired of hearing “no” from everyone. Especially when it is followed by: “You’re not old enough.” Can she go all the way to California by herself to visit her mom? “Not on your life,” says Dad. Can she do something more exciting than handing out maps at the Great Ordinary Fair along with the rest of Mr. Bland’s class? “Not until next year, when you’re in fifth grade,” answers Mr. Bland.

Fiona sets out to prove that she is, in fact, old enough to do things on her own—and ends up babysitting chickens in the fair’s poultry pavilion. It’s not easy being trustworthy and mature, especially when nobody is paying attention. But when the feathers start to fly at the Great Ordinary Fair, Fiona sticks her neck out for a new friend (and a bunch of chickens) and learns a few things about herself and what it means to take responsibility, even when things go really wrong.

Excerpt

Don’t Chicken Out • Chapter 1 •

Fiona Finkelstein was flat-out tired. Talking to grown-ups always made her that way. Especially when their answer was NO SIRREE BOB, NO WAY JOSÉ, NOT ON YOUR LIFE YOUNG LADY. That was their answer a lot of the time lately.

It wasn’t the “no” by itself that was so bad. It was all of the other stuff that always and forever came along with it.

For example, just this morning, when Fiona asked her dad if they could get a real live monkey named Mr. Funbucket that she could keep in her room, Dad didn’t just say no. He went on and on forever and ever about how monkeys are not pets and how they belong in the jungle and how speaking of jungles, had she cleaned her mess of a room yet? But what she wanted to know was, why did everything have to do with her mess of a room?

Even when she pointed this out, Dad said, “Well, if you cleaned your room more often, maybe we wouldn’t have to talk about it all the time.”

“Then could I get a monkey?”

“Not a chance,” he said.

At school there were more nos.

“Can we take a field trip to California?” Fiona asked her teacher, Mr. Bland. They had just started talking about the California gold rush in social studies when Fiona brought it up.

“Sure,” said Mr. Bland. “We can leave tomorrow.” Only, he didn’t say it in a Fiona-you’re-a-genius-that’s-the-best-idea-I’ve-ever-heard kind of way.

“Oh, Boise Idaho!” said Harold Chutney, who apparently didn’t get that what Mr. Bland was really saying was N-O.

“He’s being sarcastic,” said Milo Bridgewater. “There’s no way they’d let us go to California for school.”

“Can we please get back to the gold rush?” said Mr. Bland. “If you don’t mind.”

Milo raised his hand and said, “How come we don’t ever get to go anywhere? In my old school in Minnesota, we used to go to the park and to the lake all the time.”

This isn’t Minnesota, Fiona wanted to say out loud. This is Ordinary, Maryland. And nothing much happens in Ordinary.

Mr. Bland puffed out his cheeks as the mean words started filling up his mouth. Here’s the thing about mean words: They want to get out. But Mr. Bland’s lips must have been pretty strong, because he kept those words inside until he was able to swallow them down. And when all the puffiness left his cheeks, he cleared his throat. Then he said, “As a matter of fact, we are going somewhere.”

The whole class shouted “Where?” at the same time. Fiona gripped the sides of her desk and waited.

Mr. Bland smiled and said real slow, on account of the fact that he liked kids to suffer, “To. The. Great. Ordinary. Fair.”

Fiona let go of her desk. She folded her arms across her chest. That wasn’t even close to California.

Everybody else must have noticed that too, because there was a lot of moaning and huffing from all sides. Mr. Bland said, “I guess nobody wants to hear about your part in this year’s fair.”

“I do,” said Milo.

Everybody quieted down after that, and Mr. Bland said, “Every year our school participates in the Great Ordinary Fair in some way or another. It’s a nice way to be a part of our community.”

“That might be fun,” said Milo, looking at Fiona for approval.

Fiona chewed on her Thinking Pencil. The fair might not be a trip to California, but it could still be okay, as long as they could be in charge of games or rides or even parking. Anything except . . .

“Maps,” said Mr. Bland. “Our class is in charge of handing out maps.”

Fiona moaned. “Not maps! Maps are just as bad as tearing tickets.” Which is what she’d had to do at last year’s fair. Oh boy, the paper cuts.

“I don’t want to hear any complaints,” said Mr. Bland.

“I like maps,” said Harold.

“Not these kind you don’t,” said Fiona. “These aren’t treasure maps, you know.”

Harold plugged his nose with his finger in a pout. “Oh.”

“What about parking attendants?” asked Fiona. “Could some of us maybe be parking attendants instead?”

“Mrs. Weintraub’s fifth grade has that covered,” he said.

“No fair.”

“Enough,” said Mr. Bland. “Now back to the gold rush.”

• • •

In the cafeteria, Fiona’s mind was stuck in California. How she could get there. How she could see her mom again. Fiona’s mom was an actress in California, and lately Fiona saw her more on TV than she did in real life. And that wasn’t working out.

Without even thinking, Fiona bit into the corned beef sandwich that Mrs. Miltenberger packed. She even chewed and swallowed it.

The next thing she knew, her best friend was waving her hand in front of Fiona’s face. “Hello?” said Cleo Button.

“Huh?” Fiona’s brain snapped back to Ordinary. She swallowed. Why did she have that awful taste in her mouth?

“What’s the matter?” said Cleo.

Fiona pulled apart her sandwich and examined its insides. “Ugh. Corned beef.” She gulped her milk to wash away the taste.

Cleo cracked her knuckles. “Maybe your mom will come here.”

Milo and Harold shot Cleo a Doom Scowl loaded with extra Doom, because Fiona’s mom living in California had been a sore subject lately. Which apparently Cleo had forgotten.

“Sorry,” Cleo whispered.

Fiona passed her sandwich to Harold. “Maybe I’ll just go to California myself.”

Harold and Milo laughed. Cleo said, “Good one.”

Fiona felt her cheeks burn. “What’s so funny? I could go to California. I could.”

“Sure,” said Milo.

“I mean it,” said Fiona. “I could.”

Harold bit into Fiona’s sandwich and said, “Grandma says you can do anything that you set your mind to.”

Fiona nodded and smiled. “See?” And then she covered Harold’s mouth with her hand. “That’s gross, Harold.”

Harold swallowed and pushed her hand away. “But there’s no way she would approve of you going to California all by your lonesome.”

Fiona huffed. “Fine.”

Milo jumped in. “You haven’t ever been on an airplane before, have you?”

“What does that have to do with anything?” said Fiona.

“It has to do with the fact that kids aren’t allowed to get on airplanes by themselves if they’ve never been on one before,” said Milo. “It’s a rule.”

“I never heard of that rule,” said Cleo.

“You’re making that up,” said Fiona.

“Am not,” he said. “My brother told me about it. And he’s in eleventh grade, so he knows.”

“Fiona has too been on a plane before,” said Harold. “Remember when we went to the airplane museum last year and we got to sit inside the cockpit?”

“You’re not helping, Harold,” said Fiona.

Fiona Finkelstein was flat-out tired. Talking to grown-ups always made her that way. Especially when their answer was NO SIRREE BOB, NO WAY JOSÉ, NOT ON YOUR LIFE YOUNG LADY. That was their answer a lot of the time lately.

It wasn’t the “no” by itself that was so bad. It was all of the other stuff that always and forever came along with it.

For example, just this morning, when Fiona asked her dad if they could get a real live monkey named Mr. Funbucket that she could keep in her room, Dad didn’t just say no. He went on and on forever and ever about how monkeys are not pets and how they belong in the jungle and how speaking of jungles, had she cleaned her mess of a room yet? But what she wanted to know was, why did everything have to do with her mess of a room?

Even when she pointed this out, Dad said, “Well, if you cleaned your room more often, maybe we wouldn’t have to talk about it all the time.”

“Then could I get a monkey?”

“Not a chance,” he said.

At school there were more nos.

“Can we take a field trip to California?” Fiona asked her teacher, Mr. Bland. They had just started talking about the California gold rush in social studies when Fiona brought it up.

“Sure,” said Mr. Bland. “We can leave tomorrow.” Only, he didn’t say it in a Fiona-you’re-a-genius-that’s-the-best-idea-I’ve-ever-heard kind of way.

“Oh, Boise Idaho!” said Harold Chutney, who apparently didn’t get that what Mr. Bland was really saying was N-O.

“He’s being sarcastic,” said Milo Bridgewater. “There’s no way they’d let us go to California for school.”

“Can we please get back to the gold rush?” said Mr. Bland. “If you don’t mind.”

Milo raised his hand and said, “How come we don’t ever get to go anywhere? In my old school in Minnesota, we used to go to the park and to the lake all the time.”

This isn’t Minnesota, Fiona wanted to say out loud. This is Ordinary, Maryland. And nothing much happens in Ordinary.

Mr. Bland puffed out his cheeks as the mean words started filling up his mouth. Here’s the thing about mean words: They want to get out. But Mr. Bland’s lips must have been pretty strong, because he kept those words inside until he was able to swallow them down. And when all the puffiness left his cheeks, he cleared his throat. Then he said, “As a matter of fact, we are going somewhere.”

The whole class shouted “Where?” at the same time. Fiona gripped the sides of her desk and waited.

Mr. Bland smiled and said real slow, on account of the fact that he liked kids to suffer, “To. The. Great. Ordinary. Fair.”

Fiona let go of her desk. She folded her arms across her chest. That wasn’t even close to California.

Everybody else must have noticed that too, because there was a lot of moaning and huffing from all sides. Mr. Bland said, “I guess nobody wants to hear about your part in this year’s fair.”

“I do,” said Milo.

Everybody quieted down after that, and Mr. Bland said, “Every year our school participates in the Great Ordinary Fair in some way or another. It’s a nice way to be a part of our community.”

“That might be fun,” said Milo, looking at Fiona for approval.

Fiona chewed on her Thinking Pencil. The fair might not be a trip to California, but it could still be okay, as long as they could be in charge of games or rides or even parking. Anything except . . .

“Maps,” said Mr. Bland. “Our class is in charge of handing out maps.”

Fiona moaned. “Not maps! Maps are just as bad as tearing tickets.” Which is what she’d had to do at last year’s fair. Oh boy, the paper cuts.

“I don’t want to hear any complaints,” said Mr. Bland.

“I like maps,” said Harold.

“Not these kind you don’t,” said Fiona. “These aren’t treasure maps, you know.”

Harold plugged his nose with his finger in a pout. “Oh.”

“What about parking attendants?” asked Fiona. “Could some of us maybe be parking attendants instead?”

“Mrs. Weintraub’s fifth grade has that covered,” he said.

“No fair.”

“Enough,” said Mr. Bland. “Now back to the gold rush.”

• • •

In the cafeteria, Fiona’s mind was stuck in California. How she could get there. How she could see her mom again. Fiona’s mom was an actress in California, and lately Fiona saw her more on TV than she did in real life. And that wasn’t working out.

Without even thinking, Fiona bit into the corned beef sandwich that Mrs. Miltenberger packed. She even chewed and swallowed it.

The next thing she knew, her best friend was waving her hand in front of Fiona’s face. “Hello?” said Cleo Button.

“Huh?” Fiona’s brain snapped back to Ordinary. She swallowed. Why did she have that awful taste in her mouth?

“What’s the matter?” said Cleo.

Fiona pulled apart her sandwich and examined its insides. “Ugh. Corned beef.” She gulped her milk to wash away the taste.

Cleo cracked her knuckles. “Maybe your mom will come here.”

Milo and Harold shot Cleo a Doom Scowl loaded with extra Doom, because Fiona’s mom living in California had been a sore subject lately. Which apparently Cleo had forgotten.

“Sorry,” Cleo whispered.

Fiona passed her sandwich to Harold. “Maybe I’ll just go to California myself.”

Harold and Milo laughed. Cleo said, “Good one.”

Fiona felt her cheeks burn. “What’s so funny? I could go to California. I could.”

“Sure,” said Milo.

“I mean it,” said Fiona. “I could.”

Harold bit into Fiona’s sandwich and said, “Grandma says you can do anything that you set your mind to.”

Fiona nodded and smiled. “See?” And then she covered Harold’s mouth with her hand. “That’s gross, Harold.”

Harold swallowed and pushed her hand away. “But there’s no way she would approve of you going to California all by your lonesome.”

Fiona huffed. “Fine.”

Milo jumped in. “You haven’t ever been on an airplane before, have you?”

“What does that have to do with anything?” said Fiona.

“It has to do with the fact that kids aren’t allowed to get on airplanes by themselves if they’ve never been on one before,” said Milo. “It’s a rule.”

“I never heard of that rule,” said Cleo.

“You’re making that up,” said Fiona.

“Am not,” he said. “My brother told me about it. And he’s in eleventh grade, so he knows.”

“Fiona has too been on a plane before,” said Harold. “Remember when we went to the airplane museum last year and we got to sit inside the cockpit?”

“You’re not helping, Harold,” said Fiona.

About The Illustrator

Victoria Ying

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (May 21, 2013)

- Length: 176 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416979296

- Ages: 6 - 10

- Lexile ® 600L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Don't Chicken Out Hardcover 9781416979296(1.6 MB)