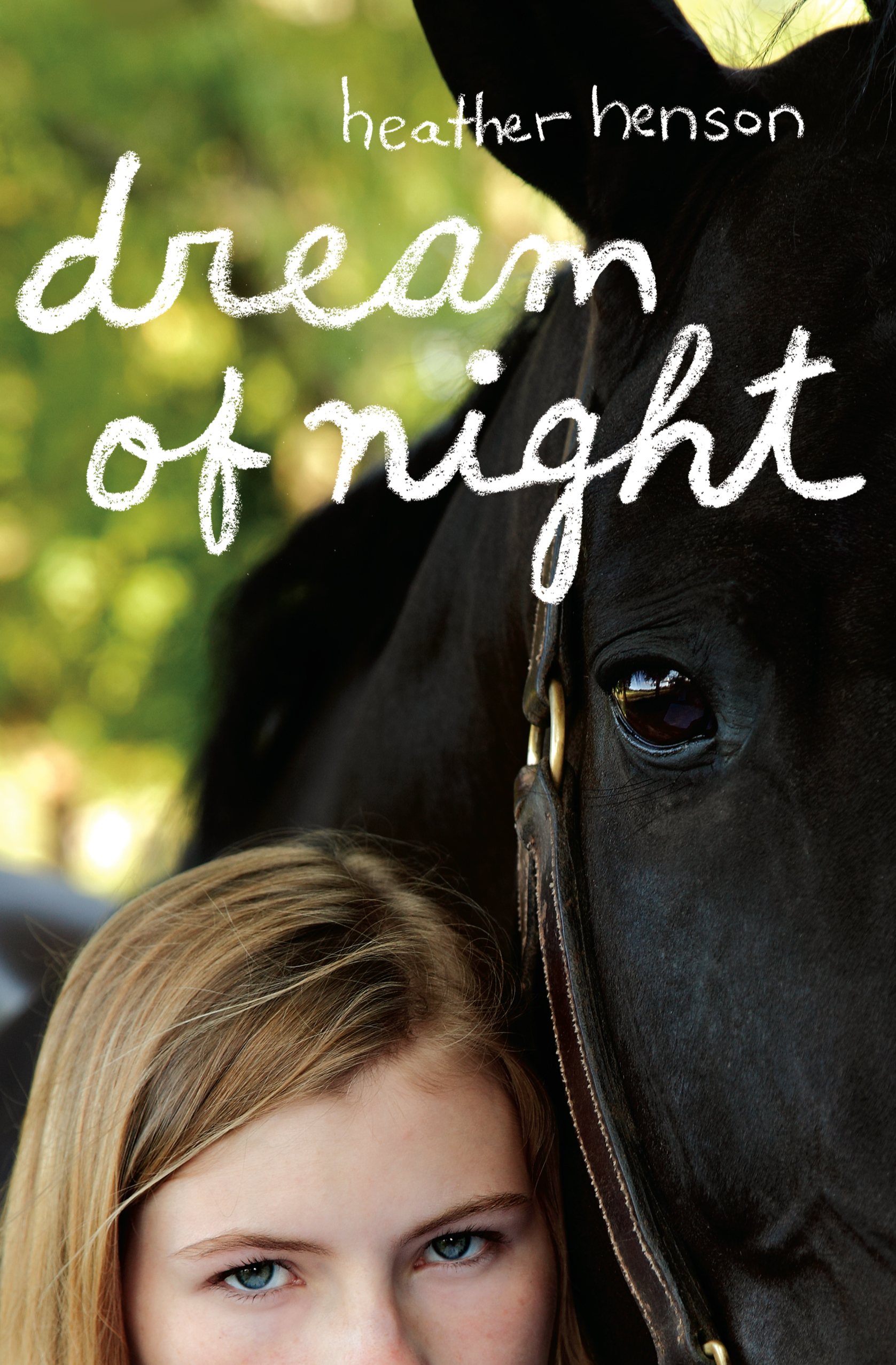

Dream of Night

LIST PRICE $17.99

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Jess is giving them a second chance, a last chance—but she fosters animals and children like this for a reason—she’s a little broken, too. And she knows what it’s like to have lost nearly everything she loves. As the horse warms up to the girl and the girl lets her guard down for the horse, the three of them become an unlikely family. They recognize their similarities in order to heal their pasts, but not before one last tragedy threatens to take it all away.

Excerpt

NIGHT

Brrr—

The sound comes sudden and sharp. Shrill. Like the call of a bird, but not. The sound is not a living sound — somehow he knows that — and it is everything.

rrrr —

The sound is flight, freedom.

nnnng —!

The sound makes his legs move. Before his brain even knows. He is moving. Exploding through the metal gate. Into space.

Not empty space. No. There are bodies in the way, blocking him. But he will move through the bodies just like he moved through the gate. Except he is being held up by the man on his back, and this makes him angry.

And so he fights. And fights. And fights.

To run.

To be faster than the rest.

To be leader of this pack.

To be the winner.

Tight inside the rush of bodies he smells rage and joy. He smells fear. He does not know which makes his legs move faster. All he knows is that he must run.

And so he does. He runs and runs and runs, and around the turn the man lets him go.

A little.

Bodies still in the way but now he can see the empty spaces between them. Because it’s the empty spaces that matter in a race. An inch, a moment, a breath to slip through.

Open.

Close.

Open.

Close.

It’s that quick. The space between the bodies. Too quick to think about. Time only to move.

And that’s what he does.

Move.

One by one the bodies fall away. Until only two remain.

And still the man on his back won’t let him go and still he keeps on fighting. It’s all he knows how to do.

Fight and fight and fight. And run. As fast as he can possibly. Run. Just to be the best, the first, the winner of this race.

Nothing to hold him back now. Not even the man on his back. He is faster than the rest and he knows it and the man knows it and so the man lets him go at last.

Two bodies.

One.

Open space.

And that’s when he hears it. That’s when he always hears it. The sound that makes him run even faster.

A great roaring. Like the wind. Fierce and terrible. And beautiful, too. The most beautiful sound in the world.

Because the roaring means that he is winning, that he is flying.

Dream of Night is flying through air.

Eeeeee!

And then he isn’t.

Eeeeee!

Something ripping him out of that time, long ago, when he was a winner. Something pulling him back to where he is now.

Eeeeee!

The ground rumbles and shakes beneath his hooves. Light tears at the darkness. The roaring inside his head has disappeared.

Eeeeee!

He lifts his nose, inhales deeply. What he smells is fear and confusion. Panic.

What he smells is man.

“Hiya, hey! Hey! Hey!”

“Watch it! Whoa, whoa!”

Ears cupping the voices.

None belong to the man with the chains, but it doesn’t matter. All men are the same. He hates every one.

“This sure’s a wild bunch!”

“You said it.”

“Get ’em to go this way.”

Now he understands. Men have come to this place, strangers. And the mares are screaming, wild and frantic, to protect their young.

He lifts his head higher, calls out, but the mares can’t hear. They are beyond hearing.

And so he stomps his hooves into the hard ground.

Pain like fire burns up his front legs, but he ignores it. He takes a great breath and rears back with every bit of strength he has and lets his hooves smack against the hard wood of the stall door.

Bang!

“Hey, did you hear that?”

“I think there’s one over here.”

Cupping his ears again, waiting. He knows the men are coming close. He can smell them and he can feel their eyes upon him now, watching through the slats of his stall.

“Getta load of the size of him!”

The voice does not belong to the man with the chains, but it makes no difference. He readies himself.

“He’s a big’un all right.”

A low whistle.

“I bet he was a looker in his day.”

Ears flat back against his skull. Waiting, waiting.

“Not very pretty now. Take a look at those bones! He’s starved near to death.”

“Last legs, I’d say. Poor old fella.”

The scrape of the bar being lifted; the creak of hinges.

He snorts, lowers his head, waiting. A new strength is pulsing though him. The fire in his legs doesn’t matter at all.

“Hey there, big fella. How ya doin’?”

It is dark inside the stall but he can see the shape of a man coming forward, hand outstretched.

“Hey there, boy.”

Waiting, waiting until the man is close enough.

“Hey, old boy.”

Rearing back with all his might. Head up, hooves ready to strike.

“Look out!”

“Get back!”

The door slams shut — just in time.

Hooves striking wood, a hammer blow. Splinters flying into the air.

Bang! Bang!

“You okay?”

“That was close!”

Rising up again for another strike as the metal bar scrapes back into place.

Bang! Bang!

Bang! Bang!

“Whew, what a nutcase!”

“Wonder how long he’s been in there?”

“Take a look at that stall. Filthy. I’d be a nutcase too.”

He waits now, head low. The air is hard to breathe. The pain is white-hot. But he won’t give in.

The men are stupid enough to make another attempt. They click their tongues and talk in soft voices.

He feels only contempt. How can the men think they can trick him with their soft ways? Soft ways to hide the meanness, the need to hurt.

Bang! Bang!

“I think we’re gonna need extra hands.”

“Yeah, I think you’re right.”

His whole body is on fire now, flickering, trembling. Still he kicks and kicks and keeps on kicking. Long after the voices fade away. Long after the screaming of the mares stops and the only sound is the rain, gentle now against the tin roof.

Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!

Morning light is creeping, dull and gray, outside the barn. It pokes through the wooden slats and falls in faint bars across the dirt floor.

Bang! Bang!

Still he kicks and kicks and keeps on kicking. It’s all he can do. Because he cannot run.

SHILOH

Brrrr —

In the shadowy dark the sound is cut off before it has any chance to bloom. Before it has any chance to wake up the old couple sleeping down the hall.

The girl does not say a word as she picks up the receiver and holds it to her ear. Not like she used to, like a dumb baby.

Hello?

And then repeating it. Like a dumb baby.

Hello?

Hello?

Hello?

The first time, years ago, there’d been a click in the middle of the train of wobbly hellos. The sound of dead air. Her own dumb baby voice.

Hello?

Hello?

Hello?

There’d been the tears she couldn’t stop.

Hello? Is that you? I know it’s you. When are you coming back for me?

There’d been only the dial tone. Nothing else.

And so she learned from then on to be silent. She learned not to cry. She learned to pick up the phone at the first sound and put it to her ear and just listen.

Silence.

That’s all. But it makes no difference.

The call is what matters. The person on the other end is what matters, and the day of the year. The one day of the entire year the call will come.

Of course the girl never knows the time. It could be morning or afternoon or night. (Although more often it is night, when other people might be in bed.) Even so, she has to always be on guard, listening, waiting. She always has to be the first one to the phone.

This isn’t always possible, in all the different places she’s lived over the past few years. One place didn’t even have a phone, it was such a dump.

But this place does. The phone is in the kitchen and the old people are down the hall and anyway they sleep soundly through the night. And so when the call finally comes the girl puts the phone to her ear and listens and hardly breathes.

Sometimes if she listens hard enough she can hear a hint of something. The rustle of clothes or the clink of ice cubes in a glass. The sizzle of fire and ash.

Tonight when she closes her eyes she can smell cigarettes, even though the old couple doesn’t smoke. She can smell perfume, like candy. Sweet.

When she closes her eyes and smells the perfume and the smoke she can wait. And wait. She can wait forever if she has to, although she hopes she doesn’t have to. She hopes one day, if she’s quiet enough, there will be a voice on the other end. But for now this is enough.

The girl waits and listens.

Maybe she can hear another sound now. Wet and soft. Steady. Rain? Is it raining there, too?

How far away does her mom live from the old couple’s house? How far as the crow flies? Because that’s what people say when they mean a place is closer than it seems. As the crow flies.

“W-w-wh-wh-wh…”

All at once the noise explodes out of the silence and the girl nearly drops the phone she is so surprised.

“W-w-wh-wh-wh…”

Like a siren, a police car coming closer and closer.

The girl knows all about police cars and ambulances. But this sound, it isn’t a siren. This sound is human.

“W-w-w-whaaaaa! Whaaaaaaa!”

Somebody is crying.

Not the girl of course. She never cries anymore.

Somebody is crying on the other end of the phone.

“Shhhh-shhhhh-shhhh.”

And somebody is trying to shush the crying, stop it before it grows louder.

“Shhh-shhh-shhh.”

Getting more desperate.

“Sh-sh-sh-shhhhh.”

Somehow the girl knows the “sh-shhing” isn’t going to work. She can tell the baby — because that’s what it is — the baby is going to rev itself up instead of down, even with the “shhhh-shhh-shhhh”s. The girl has heard enough babies crying in the places she’s been. She’s met enough people who must have thought they wanted a baby but didn’t when they found out how much trouble they are. When the babies cry and cry and won’t stop crying.

“Shhhh! Shhhhhh!”

“Whaaaaaa-whaaaaaa!”

When babies cry like that in the places she has been, people usually tell them to shut up.

“Meet your sister.”

The girl clutches the phone closer. Her heart nearly stops dead in her chest.

“A screamer.”

The voice is exactly how she remembers. Low and gravelly. From the cigarettes.

“Just like you.”

The girl opens her mouth. Is she supposed to talk now? Is she supposed to answer back? What does her mom want her to do?

“Happy birthday, Shy.”

Click.

And it’s over. Just like that.

One click, and the sound of her mom’s voice and the siren cry of the baby (a sister, she has a sister!) are gone.

Click.

Like they were never there at all.

JESSALYNN

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

The sound comes from nowhere and everywhere.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

The woman tries to ignore the sound. She tries to stay in the cozy dark and hold on. To where she is. To the bundle in her arms. But she can’t.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

The sound is already reaching through the darkness, hooking her like a fish and yanking her upward, arms empty.

“Hello? Hello! Jess! Hey, girl, wake up! Jess! Wake up!”

The woman recognizes the voice. Too loud for this time of night — or morning. Is it morning already?

“Jessalynn DiLima! Haul it outta bed, girl! E-mer-gen-cy. I’ll be there in thirty.”

Click.

Ah, now the woman can return to the dark. Sink back into darkness. Ignore the doorbell when it rings.

E-mer-gen-cy.

Eyes open. Just a squint, but open.

E-mer-gen-cy.

The curtain edge holds the barest hint of light. Rain pattering against the glass, soft and low. A vague memory of something harder, of thunder and lightning deep in the night.

The woman squints at the bright red numbers hovering on the bedside table. Morning, for sure. Way too early.

“I’m going to kill you, Nita.”

The old redbone hound dog draped at the woman’s feet lifts her head, thumps her long tail once.

“It’s okay, Bella. You don’t have to get up.”

The dark wet eyes have a guilty look. Or maybe the woman is just imagining it. Not so long ago the dog would have been up like a shot, ready for anything. But now there’s a dusting of white along her muzzle. The dog’s head drops back onto the faded quilt.

The woman sits up and swings her legs over the edge of the bed. She stretches her arms into the air.

“Ahhh!”

A spasm of pain.

Slowly, carefully this time, she tries again, stretching, rising to her feet. Gently she kneads her thumbs into the small of her back.

Mornings mean stiffness now. Stiffness means she’s getting old.

“Too old for e-mer-gen-cies at four thirty in the morning,” she grumbles, but of course there’s no one to hear. The dog, Bella, has already gone back to chasing rabbits in her dreams.

One

SHILOH

She’s not doing it for the woman. She’s doing it for the black horse.

Mornings now Shiloh takes the bucket of warm bran mash to the field, hooks it on the gate, and then she switches buckets again, full for empty, late in the afternoon.

“Do you want to see how I mix it up?” Mrs. Lima Bean asks, after Shiloh has been feeding Night for a couple of days. “You don’t have to. I just thought you might want to do it on your own.”

Shiloh shrugs. But she doesn’t say no.

“It’s like mixing up oatmeal,” the woman says.

“I don’t like oatmeal. It’s gross.”

“I never liked oatmeal either.” The woman acts like she’s telling a secret. “But the horses love this stuff. And know what? We put medicine in it. So he’ll get better.”

The woman shows her how much medicine to put in, how to mix it. Shiloh can’t believe Mrs. Lima Bean lets her do it on her own. Isn’t she worried that Shiloh will get it wrong? That she’ll put too much or too little?

One foster freak used to act like she wanted all the kids to bake cookies together, but then she’d get mad if they didn’t measure the flour and the sugar exactly right. She’d make them dump it out and start all over again.

“Night is getting used to you,” Mrs. Lima Bean says, handing over the bucket of warm mash. “I think he’s starting to trust you.”

“So?” Shiloh says, but she turns away so Mrs. Lima Bean won’t see.

The flicker of a smile.

At the gate she switches buckets. Full for empty. The black horse won’t come right away. He keeps his head down. He acts like he doesn’t care. But she knows. He wants to gulp it down. He’s hungry. Maybe he’ll always be hungry. After being starved. Maybe he’ll never be able to get enough food.

The black horse snorts hard through his big nose, and then he takes an uneven step forward, another. Limping a little. He stretches his neck out and nudges the bucket, breathes and snorts again. Looks away. Moves closer.

“I don’t care if you eat it or not.”

The black horse flicks his ears back. He’s annoyed. She can tell. The ears go flat when he’s annoyed. The ears always go flat when he’s about to scream at Mrs. Lima Bean.

“No skin off my back.”

Shiloh turns and starts to walk away. But she hears the bucket clang against the gate. And she can’t help it. She turns and wanders back.

Night has his nose in the bucket, chowing down. He lifts his head a moment, flicks his tail, starts eating again.

“I don’t know how you stand that stuff,” she says. “It’s disgusting.”

He lifts his head, still chewing mash, grain spilling out between his teeth.

“Don’t chew with your mouth open.”

Night cocks his ears and then puts his nose back in the bucket.

The sun is bright today. Night’s scars are uglier than ever, the ones around his neck thick and raw.

“I have scars. Just like you.”

Shiloh glances over toward the barn to make sure Mrs. Lima Bean is still with the other horses. “Wanna see?”

Shiloh puts the bucket down and pulls at the neck of her T-shirt so that her shoulder pokes through.

“It hurt, I guess.”

She doesn’t touch the scars. She never likes to.

“I don’t remember. I was little.”

She can’t explain. She hasn’t. To anyone. How the fear is what she remembers. More than the pain.

And Slade’s face. The way he grinned when he was angry so that you wouldn’t know at first. That’s why you couldn’t always get away in time. Because at first you thought he was laughing because he was happy, because he was glad. Because he liked you.

But then you knew.

And maybe there was time to run into the closet. And maybe there wasn’t.

But it didn’t matter. Because there was never a closet big enough for her mom.

“My mom left him,” Shiloh says. “I know she did. She probably had to take out a restraining order on him. That’s what people do when somebody’s dangerous. She probably had to hide so she could get her head straight.”

Night is watching the ground, his ears flicking forward and back. It doesn’t matter if he’s listening or not. Shiloh tells herself it doesn’t matter.

“That’s why I can’t be with her yet. She has a new apartment and a new baby and she has to hide, but now she wants me to watch my sister so she can get a job. That’s all she needs. A good job.”

And no Slade.

Shiloh thinks it. Inside her head. She doesn’t say his name out loud. Ever. Because if she says his name out loud, it’s like he’s there with her. It’s like he’s real and not inside her head, inside her dreams. She knows dreams aren’t real. She knows the things inside her head are memories and so they can’t hurt her. Not really. But if she says his name out loud, she’s not sure what would happen. She’s not sure he couldn’t find her mom, find her baby sister. She’s not sure Slade couldn’t find her.

Shiloh looks up at the black horse. He’s so big. She doesn’t understand how he got his scars. How he would let anyone hurt him like that. With his hooves and his screaming and his legs kicking out. It makes her angry. She can’t explain it, but she’s angry at the black horse for letting himself get those scars. She turns abruptly away. She walks toward the house. Without looking back.

If she were big, like Night, if she were big and fierce and strong, she would never let anyone near. She would never let anyone touch her ever again.

JESSALYNN

The woman is watching from the back of the barn. A skinny opening where the boards have come loose. She’s not spying. She would never spy. But she needs to know. She needs to see for herself.

The girl and the black horse.

Together at the gate.

The girl’s mouth is moving. She is talking. More than she has to Jess. More than she has to anyone, probably.

And the black horse is just standing there.

He isn’t screaming.

He isn’t even looking at Shiloh for the most part. But Jess can tell.

The black horse is listening.

NIGHT

It makes no difference. Who brings the food. The woman or the child. He would still refuse it if he could.

And he could still hurt the child. Even though she has touched him. Even though he has let her touch him.

The child brings the food and she talks to him, and he listens. But he could still hurt her if he wanted to.

Sometimes he wants to. Especially when she leans over the gate to take the empty bucket. Her skinny arm reaching into his field. He could sink his teeth into her flesh, and she would cry, and the bite would leave a mark. And maybe she’d never come to the field again, and that would be okay. He tells himself it would be okay.

Except.

He knows what she sounds like now. Her feet on the gravel. Dragging a little. As if she can’t lift her feet all the way.

He knows what she smells like. Fear and anger, and something else mixed in. Something that he doesn’t understand, but thinks must be a human child smell.

He knows her voice. Small, like the rest of her, faint, as if she is afraid someone will hear her. But when something startles her, the voice changes. The voice smacks against him. And he wants to stop the voice. But he doesn’t.

He could scream at her to make the voice stop.

But he doesn’t.

He waits.

And the voice goes soft again.

And every morning, after the sun has come up, he waits. But he tells himself he isn’t. Waiting. For her.

One

JESSALYNN

Brrrr-

The familiar sound. Annoying, like a lone mosquito.

-nnnnnnng.

Jerking her out of sleep.

Brrrr-

If she ignored the sound, would it stop? How many rings would it take to stop? She doesn’t have an answering machine.

-nnnnnnng!

Old-fashioned and impractical, she knows. Stubborn, Nita calls it. But here’s how Jess sees it: If somebody wants to get hold of her, they’ll call back when she’s home.

Brrrr-

“Hello?”

In the end it’s too hard to ignore a ringing phone, in case it is an emergency of some kind.

“Hello?”

The usual emptiness. On the other end. Some breathing starting up. Raspy-sounding. A clinking. Ice cubes, maybe?

“You really must have the wrong number.”

The clock says it’s three. In the morning. Not exactly the same time as the other nights, but pretty close.

“Or else you’re doing this to be funny. It’s not funny. It’s becoming a nuisance now. Please stop.” She pauses, and then says it again, more firmly. “Please, stop.”

After she’s hung up, she sinks her head back onto the pillow, stares up into the dark. Bella’s warm body shifts along one leg. Jess thinks she’ll get up like usual, go check on the girl, see to Night. But her body feels too heavy tonight, too hard to move. She closes her eyes, and slips soundlessly back into sleep.

SHILOH

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

Eyes popping open.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

A phone ringing. Not just inside her dream anymore. A real phone.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

The girl jerks up and out of bed. Her heart is thudding so loud she can’t hear anything else.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

Except the phone.

It’s her mom calling. She knows. Even though it’s nowhere near her birthday. Who else would call in the middle of the night?

Brrrr-

The sound is cut off, and the girl wants to scream. But she makes herself keep quiet as she opens the door and tiptoes down the hall.

She knows there’s a phone downstairs, in the kitchen. But there’s another phone in the woman’s bedroom.

And so she waits. And she hears it. A voice. Mrs. Lima Bean’s voice.

Shiloh holds her breath and listens.

The woman is telling the person on the other end to stop calling in the middle of the night, that it’s a nuisance. To please stop.

Shiloh wants to crash through the door and yank the phone away from the woman.

But she doesn’t, can’t. Because the woman hangs up before she even has a chance. The call is over.

Shiloh waits to see what the woman will do. She knows the woman doesn’t always sleep through the night. She’s heard her get up and go down the stairs, move around the kitchen.

But tonight the woman stays in bed. After a few minutes Shiloh hears a light snoring.

Will her mom try to call again? Tonight? Tomorrow? When?

And why is her mom calling when it’s not her birthday?

Maybe it’s not her mom at all. Maybe it’s a total stranger.

But it must be her mom. It has to be.

And she’s calling to say that she’s ready. She’s ready for Shiloh to come to her.

Shiloh knows it’s a secret. Her mom calling. She knows her mom isn’t supposed to call at all. Ever. Her mom’s not even supposed to know where Shiloh is.

And yet.

She has called. She has known. Every time Shiloh’s moved. Every time she’s in a new place, on her birthday. Her mom has called. Somehow she’s found out.

And now, Shiloh’s been sleeping through the calls. Like a dumb baby. Shiloh messed up. But her mom has to give her another chance, right? She has to.

Shiloh goes back down the hall to her room. She ducks into the closet to check the suitcase, to make sure everything is packed, ready to go.

The phone will ring tomorrow. Shiloh knows it will. And she’ll be there to answer it.

One

SHILOH

Brrrrrr —

The girl picks up the receiver. She’s been waiting. A whole year. And now she’s ready.

“Mom.”

No click. And so she takes a deep breath. She has a lot to say.

“I’m living on a farm now. I’ve been here awhile. I didn’t like it at first. I didn’t like Jess. But now I think she’s okay. She’s kind of old, like a grandma, but she’s teaching me to ride horses. There’s this one horse. His name is Night. He lets me brush him now. Which is a really big deal because he used to not let anybody even go near him.”

She waits, giving her mom a chance.

“Night’s all black. He used to be a racehorse. We rescued him. Well, Jess rescued him. And then I helped. He won’t let anybody brush him except me. Well, sometimes he’ll let Jess. But he used to scream at her all the time. He used to scream at everybody, except me. It sounds like a person screaming. It really does.”

Pausing for air.

“Night protected me. This guy tried to hurt me last year, and Night protected me. I know that sounds weird because he’s just a horse. But he’s smart. He can sense things. Because this man tried to steal him back, and I was there, so the man attacked me because he was drunk and mean. And Night knew, and he stopped the guy.”

Another deep breath.

“And we almost lost Night because of that. People thought he was a dangerous horse. Because he hurt the man, kicked him in the head and killed him just like that. But it was an accident, and Jess made them see. She went to the judge and everything. She made them see. Night was only trying to protect me.”

Shiloh stops. She thinks she hears something on the other end. Crying. Is it her little sister crying? How old is her sister now? She can’t be a baby anymore.

And then Shiloh knows. It’s not a child crying.

“I’m okay, Mom,” she says, quiet but firm. The way Jess talks to the horses when they’re upset. “I’m okay, really. You don’t have to worry about me. And you can still call on my birthday. But you can call some other times too. If you want.”

Shiloh’s throat is getting tight. Hearing her mom cry like that. But she has more to say.

“I don’t know how you get the phone numbers. The state lady says you’re not supposed to know. Where I am. She says there’s no way you could’ve had all those numbers, the places I lived. Unless somebody’s telling you when they’re not supposed to. In the state lady’s office. But I’m glad. I’m glad you call sometimes.”

Shiloh stops now. Her voice is getting too wobbly. She doesn’t want her mom to think she’s still a baby. A crybaby. Because she’s not. She’s one tough cookie. Jess has told her so.

“Happy birthday, Shy.”

The voice comes out low and gravelly, like Shiloh remembers. Shiloh presses the phone to her ear. She wants more. Because she loves her mom’s voice. The very sound. It would be the best birthday present ever. If her mom just kept on talking.

“I guess I didn’t tell you before. Your sister’s name is Madison. I call her Maddie.”

A slow intake of air, on the other end. A cigarette maybe, or her mom just trying to catch her breath.

“Her middle name is Hope.”

Shiloh lets it roll around inside her head.

Madison Hope.

Shiloh Grace.

Sisters.

“Maybe Maddie can come see the horses sometime.” Shiloh can’t stop herself. The words rush out. “Maybe you could bring her, and you all could meet the horses. And Jess.”

Silence.

“Not right now,” Shiloh jumps in quickly. “But sometime.”

Shiloh waits. And waits. She’ll wait forever if she has to. But she hopes she doesn’t have to.

“Maybe we will, Shy. Sometime.”

More silence, and then the click. And the voice is gone. Like it was never there at all. But Shiloh knows. It was.

JESSALYNN

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

The woman is tugged out of sleep. A heavy, dreamless sleep.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

Because the baby is gone, vanished, like the grandchild that never was.

But that’s okay. The woman doesn’t need the dream anymore. She doesn’t need to keep reaching for something she already has.

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

Jess plucks up the receiver, squints at the numbers on the clock.

“Okay, Nita, what’ve we got?” she asks instead of saying hello.

“Big emergency. Bunch of horses. I don’t know how many. Abandoned by the side of the road. Can you believe it? The sheriff’s stopping traffic. I’ll pick y’all up in thirty.”

Click.

Jess allows herself a couple of minutes, and then slowly, carefully, she pushes herself up and out of bed. Stretching, making her way into her clothes.

Bella’s eyes follow the motions, but her body shows no hint of doing the same.

“It’s okay, girl.” The woman cups her hand under the dog’s muzzle. “Stay in bed.”

Jess heads down the hall and taps at the bedroom door.

“I heard the phone!” the girl’s voice calls right away. “I’m up.”

“Nita will be here in about thirty minutes.”

“I’ll be ready.”

In the kitchen Jess starts the coffee, drops a couple of slices of bread into the toaster.

“I’m not hungry,” Shiloh says, breathless, as soon as she bursts into the room, pulling on her jacket already.

“It’s going to be a long day,” Jess warns.

“I know!” A click of the tongue. “You don’t have to tell me. I’ve done this before.”

“Once,” Jess says, under her breath.

The girl rolls her eyes, but she takes the peanut butter toast, gulping it down as fast as she can.

“I’m going out to check on Night before we go.”

Shiloh grabs an apple from the bowl on the counter and tucks it into her jacket pocket.

“Better take more than one of those,” Jess gently warns. “Can’t be showing up in a barn full of horses with just one apple.”

Shiloh clicks her tongue again, but her pockets are full by the time she bangs through the kitchen door.

Jess stands at the counter. She eats a piece of toast, pours out a cup of coffee.

Morning fog is still clinging to the ground outside the window. The day is starting out cold and gray. She’ll have to keep moving this morning if she doesn’t want to be stiff as a board come tomorrow.

At least now she has somebody to help with the chores. The girl doesn’t complain about the manure anymore. She doesn’t complain about any of the work, especially if it has to do with horses.

Jess pours the rest of the pot into a thermos for later. She glances up from the counter just in time to see Shiloh disappear into the barn. Because that’s where the black horse is. Now that it’s turning chilly at night. Inside his own stall. Right where the girl led him.

NIGHT

Brrrrnnnnnnng!

The sound comes, sudden and sharp. Shrill. Like the call of a bird, but not. The sound is not a living sound. It is only a memory. From long ago. He knows that now.

The sound. The fighting. The roaring.

They are all a part of him. But they are not everything. Not even the pain is everything, the anger. Not anymore.

There is the sun and the grass. And fresh hay and clean water. Every single day.

There is the stall, warm and dry. Walls, yes, but not a prison.

There is the woman who already smells like horses.

And there is the girl who is still angry sometimes, still afraid, but who comes to him. Every day. And who is starting to smell like horses too.

© 2010 Heather Henson

Two

SHILOH

Day breaks and Shiloh pulls the scuffed black canvas suitcase out from under the bed. Everything she owns in the world fits inside. She doesn’t even bother folding the T-shirts and jeans and shorts. They’re all hand-me-downs or Salvation Army castoffs anyway. Who cares if they are wrinkled?

A faint knock comes halfway through the packing. Shiloh ignores it. She ignores the muffled, fluttery voice, too. The door isn’t locked but she knows the old woman is too timid to open it.

When she’s done, Shiloh leaves the case where it is on the floor and folds herself into the closet to wait.

Small places are the safest. Easily forgotten.

There, on a low shelf near her head, she sees an old ballpoint pen.

Click, and it’s open.

She tests the ink on her palm. And then slowly, carefully, she writes all the bad words she knows on the pure white walls of the closet for the old couple to find later, after she’s gone.

The doorbell rings.

Click, the pen is closed. She tucks it into her jeans pocket.

The muffled sound of voices, low and secretive. She knows what the voices are saying even though she can’t actually make out the words.

We tried.

Too angry.

Too much trouble.

We’re sorry. So very sorry.

Shiloh hates the word “sorry.” One of the things she’s learned in her twelve years is that people who say they’re sorry never really mean it.

“Shiloh?”

The state lady. Just outside the door. Her voice cheerful and bright.

What a fake.

Shiloh yanks the door open. She ignores the fake smile as she walks by. She ignores the old couple sitting on the couch on her way through the TV room.

“Good-bye, Shiloh,” the old woman calls in her high, fluttery voice. “Good-bye. I hope…” The voice trailing off, as usual. “Well, I just hope…”

Shiloh doesn’t wait for her to finish the sentence. She doesn’t say anything back as she walks out the door. It doesn’t matter. She’ll never see the old woman again.

JESSALYNN

Before the pickup even rolls to a stop, Jess is out of the passenger side and making her way toward the paddock. Rain pelts her hard but it doesn’t matter. She’s used to being out in all kinds of weather. Rain doesn’t hurt unless it has some ice to it.

A great mass, dark and muddy, is wedged against the white plank fence. As Jess comes near, the mass breaks apart, screaming and snorting, becoming not just one body but many.

Becoming horses.

Skin and bone. Every one. Barely strong enough to stand, by the look of them.

Still they wrestle with all their pitiful might. Jerking their hooves up from the dark, sucking mud. Stumbling and shrieking, eyes rolling back inside their heads.

Jess takes a slow breath, gazes down at her muddy boots. The anger rises up fast. The taste of bile sharp at the back of her throat.

It’s the same every time. With this kind of rescue. It never gets any easier.

Horses shouldn’t look this way. Skeletons with a bit of skin attached.

Horses shouldn’t act this way, either. So fearful of human touch they would break off their own legs just to get as far away as possible.

“Oh, Shenandoah, I long to see you.”

The singing is a reflex. Automatic.

“Away, you rolling river.”

Soft and low. Not really meant for human ears.

“Oh, Shenandoah, I long to see you.”

A song her father used to sing when she was a girl. Many years ago.

“Away, we’re bound away, ’cross the wide Missoura.”

Most times the sound is soothing, a comfort. But not today. These horses are way too spooked.

Screaming and snorting, nostrils flared, the pack manages to pull itself up and away. As far as it can go. Until the thick mud cements hooves in place once more.

“Hey, Jess, this way!”

A voice, calling through the rain and terrible racket.

“They’re ready for us.”

The voice of “emergency.” At four thirty in the morning.

With Nita, “emergency” always means horses.

“Foster or for keeps?” Jess hears Nita asking as she comes out of the drizzle into the dry barn.

“Dunno. Court’ll decide in a month or so.”

Jess can hear the exhaustion in Tom’s voice. She can see the dark circles under his eyes when she comes up beside Nita. Tom’s in charge of this rescue. He’s probably been up all night.

“Can’t keep ’em here that long,” he continues, waving a clipboard in the air. “We’re splitting at the seams. And there ain’t enough to keep ’em all fed as it is.”

Nita nods. She knows all this. So does Jess. It’s the same story, time and again.

A bunch of sickly horses finally get rescued after being mistreated and starved, and the pain and suffering isn’t over yet. Not by a long shot. Because there’s never enough feed at the Humane Society, never enough hay. Never enough hands to help and never enough homes for the horses to go to.

“I ’preciate you gals coming out like this. On such short notice,” Tom says. “And in such great weather, too.”

“At least we’re not the only ones today.”

Nita nods toward the trucks and trailers already lining from the barn to the end of the driveway.

“Yeah, we managed to get it in the papers and on the radio first thing. Word of mouth spreads pretty quick.”

“Especially with Nita around,” Jess says under her breath. “How many calls did you make this morning, anyway?” She grins over at her friend.

Nita gives a shrug. “I lost track at twenty-five.”

“Nita Horne!” Tom cries. “I don’t know twenty-five people I could call at this hour of a morning!”

“I don’t either.” Nita winks. “I just opened up the phone book.”

Tom lets out a big laugh. “All right, then, ladies.” He taps a thick finger against the clipboard. “First one up is number ten. And she’s got a foal.”

“Two for one.”

“You got it.”

Nita turns to Jess, zipping up the hood on her rain slicker.

“You ready?” she asks.

“As ready as it gets nowadays,” Jess replies.

The women enter the paddock. Wading through mud, circling, arms fanned out. Trying to get a look at the numbers on the brass tags attached to halters, separate one horse from another, load each one up into a waiting trailer.

All this without stirring up a ripple of panic. Because a ripple builds into a tidal wave. Just like that.

“Whoa! Whoa! Watch it!”

Too late, the black mass senses danger and seizes back. Then forward, surging, a dark sea. Churning and dangerous. Barely missing Jess and another volunteer.

“You’re slowing down, old lady,” Nita calls over the roar.

“That’s what I would’ve told you this morning,” Jess mumbles, “if you’d stayed on the line long enough.”

The terrified herd settles into a far corner, and the volunteers try it again.

And again.

The rain doesn’t stop, and the mud gets thicker. A stew of woman and man and beast. Something out of a movie. A scene in old black and white runs through Jess’s head. A man alongside a muddy riverbank, wrestling alligators.

Because that’s what this is like. Sorting through this lot is like wrestling alligators. Jess loses all sense of time. And place. Maybe she has been here forever, dodging hooves and teeth. Maybe she has died and gone below, to the place her granny always warned her about.

After a while, though, the sorting starts to inch its way toward easy. Easier. The mares start to give up. Worn out, pure and simple. Broke.

Only the foals stay fierce. Wild. Determined to remain free, untouched.

It’s the same every time. With this kind of rescue. The foals are in better shape than the mares. Because they can still nurse even while their mamas are starving.

And even though she knows one of the feisty, long-legged little foals could kick her in the head if she’s not careful, Jess is glad. Just watching the foals makes her heart glad. Because it shows how life goes on. Even in the mud and misery. Life continues.

Another hour slips by, two. Jess ignores the familiar nagging in her lower back, the stiffness in her joints. The only thing that finally stops her is the time.

“Sorry, but I gotta go,” she calls to Nita, tapping a finger on her mud-splattered watch. “Got somebody coming at three.”

“Which one you taking?” Nita calls back.

“The palomino.”

No foal and sweet as pie. Worn out from all the youthful shenanigans. The old gal will fit in fine with Jess’s other horses.

“Okay, go get the truck,” Nita says. “I’ll round her up. Key’s under the flap.”

Jess nods and heads out of the barn. The rain has let up, but the clouds to the east are still dark, threatening.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

A jolt of sound, sudden and close. Like thunder, but not. At least not the kind that comes from the sky.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

It’s hooves slamming against metal, a new horse trailer pulling up. The kicking going on inside so full of force, Jess half expects to see hoofprints stamping through the walls.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

“Whoo-wee, glad we made it!” The driver is jumping down from the cab of the truck. “Not sure the trailer was going to hold.”

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

“Why didn’t you tranq ’im?” Tom has come out of the barn with his clipboard. He doesn’t look happy.

“We did!” the driver yells over the noise. “He’s got enough Ace in his veins to drop an elephant.”

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

“Lord have mercy,” Tom says softly. He stands, watching the horse trailer shimmy and shake. “Well, what’re we going to do with him now? Where we going to put ’im?”

“You tell me,” the driver says, holding his empty palms up.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

Jess checks her watch again. She’s going to be late, even if loading up the palomino is smooth and easy.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

But she can’t resist a closer look.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

And what she sees through the metal slats makes her stomach churn all over again. Because what she sees is a shell of a horse, a skeleton, barely alive, but kicking to beat the band. Kicking to show his stuff, to show what he once was.

A Thoroughbred. Jess can see it, despite the thinness and the filthy, rotting coat. A racehorse, most likely. A king, once upon a time.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

Nothing but bones now. A bag of bones and skin covered in mud.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

And scars. Thick scars winding their way around his neck like a noose. Thinner scars flicked along his sides.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

The whip, of course. But chains, too. Jess has seen it before. Willful horses chained to a barn wall to make them mind.

“Listen at that.” Tom has come up behind her. She knows he’s not talking about the kicking. He’s got his head cocked, listening to something behind that. “Pneumonia for sure. Who knows what else. Can’t let him get near the other horses. Even if he was calm as milk.” Tom tugs at his cap, lets out a sigh. “Truth is, I don’t know what to do with him. Probably best to put ’im out of his misery.” He turns away. “Shoulda done it back there before bringing him all this way, stressing him out even more.”

“Now you tell me,” the driver says.

There was a time Jess would have protested. Loudly. She would have let Tom have it. Told him how wrong he was. And she would have taken this horse home just to prove her point.

But that was before her back went out the first time, before she woke up with pain and stiffness most mornings.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

Before she got old.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

Now she’s not so sure Tom is wrong.

Out of his misery. Probably the best thing. A horse this bad off, this far gone.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

This angry. Jess is about to turn away, nothing she can do, when it happens.

The horse stops. Kicking at his cage. Just stops. And reaches his neck around. Turns his head. To look at Jess.

Is it the singing?

She hadn’t even realized. Because it’s a reflex, automatic.

Is it the melody?

A song about a river, not a girl. Her father had to explain that to her long ago. Shenandoah is a river, not a girl like Jess imagined. Not a song about love but about longing.

Is it the voice?

Doubtful. Jess knows she doesn’t have her father’s baritone, which was like an oak tree, deep-rooted, strong.

Whatever it is, the horse is looking at Jess.

And Jess is looking back.

And what she sees she can’t explain. Not in words, anyway. What she sees is what this horse once was.

A champion. A king.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

The song ends. The moment is gone.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

The kicking starts up again. Harder now. Harder even than before.

“What’s his name?” Jess asks, turning to Tom.

“Well, he’s registered. A money winner, in his day.” Tom flips through the list. “Let’s see… Here we go.” He squints up at the trailer. “Nice name. Dream of Night.”

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

“Well, he’s nobody’s dream now!” The driver spits out a wad of tobacco with the words. “More like a nightmare.”

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

“I’ll take him,” Jess says, her words getting lost in the noise so that she has to say it again. “I’ll take him.”

Tom pushes his cap back, looks at her. “I dunno, Jess. Even if he does make it through the night, he’s a wild one all right.”

“I’ll take him.” Jess says.

“No offense, ma’am, but you’re crazy!” the driver blurts.

“Nothing I haven’t heard before.” Jess winks at Tom, and he lets out another of his big laughs.

“What about this sweet gal?” Nita asks when Jess comes into the barn to sign the paperwork. She has the palomino ready to go. “She’s just a doll.” Rubbing her cheek along the mare’s muddy neck.

“Can’t take both. I’ve got to go now, and the other’s already loaded up.”

As if that’s the reason. The black horse is already loaded up.

“Thought you weren’t taking the hard cases anymore,” Nita says, some slyness slipping into her voice. “Thought you were too old.”

“I am,” Jess answers, checking her watch, letting the second thoughts worm their way in.

What in the world is she doing, anyhow? Taking on a sickly ex-racehorse at this point in her life, at this moment? She’s too old, too rickety to handle some crazed-out-of-his-mind Thoroughbred stallion. She’ll have her hands full as it is. With the kid coming, this very afternoon — Jess glances down at her watch — this very minute, in fact.

And not just any kid.

“Tough as nails,” the social worker said over the phone. “Angry at the world.”

Jess studies her muddy boots. The irony does not escape her. An angry kid and an angry horse. Both the same day.

“Where to, ma’am?” The driver has come to find her. He’s waiting.

Nita is waiting too.

“My farm’s about thirty miles from here,” Jess hears herself say.

Bang-bang! Bang-bang!

“Well, let’s just hope we make it!”

NIGHT

Nobody’s dream now. More like a nightmare.

Because he understands. As all horses do. Human talk.

Although what he knows goes beyond words. What he knows is sound. Timbre. Pitch. Meaning within a sound.

Anger. Arrogance. Fear.

What he knows is smell. The scent every living thing gives off, whether they mean to or not. And the tension, trapped inside the body, betraying the truth behind the words.

What he knows is touch.

The tug of the bit inside the mouth; the jerk of the reins; the sting of the whip.

Touch.

A slap. A punch. A kick.

What Night knows is that touch is something to be avoided at all costs.

Two

SHILOH

“I’m not doing this for you.”

There. It’s out in the open. Shiloh waits for the woman’s face to get angry. But of course it doesn’t. The woman only nods.

Shiloh looks away. She just doesn’t get it. She can never make the woman mad. And this makes her mad, makes her want to kick or punch something.

She could kick the stupid dog that follows the woman everywhere. But the dog always keeps its distance. Like now. It gives her a sideways glance and then speeds up, disappearing into the shadows of the barn.

“It’s creepy in here.”

Shiloh’s voice echoes a little. Something flutters overhead. A bird. A dumb bird is caught in the rafters of the barn. Shiloh watches the bird. She feels trapped too. She wouldn’t be in here at all if it weren’t for Night.

“I’ve spent a lot of time in here,” the woman’s voice comes from around a corner. “I feel at home in a barn.”

“That figures,” Shiloh mumbles.

“It’s always cooler in a barn, in summertime.”

Shiloh doesn’t answer. The air does feel pretty good in here, but it’s creepy just the same.

Two cats slink out from behind a board. One is gray and one is a bunch of different colors. They dart toward Shiloh and swirl like water around her ankles.

Shiloh nudges one with her toe. She’s not afraid of cats. They don’t have big teeth. You could kick a cat across the room if you needed to, if it tried to scratch.

“There was a woman in our building. She had too many cats. You could smell them all up and down the hallway. We called her the crazy cat lady.”

Shiloh stops herself. She doesn’t know why she’s telling Mrs. Lima Bean anything about her life. Maybe one day she’ll be telling somebody that she lived with a crazy horse lady.

“The cats keep the horses company,” Mrs. Lima Bean says, her voice a little breathless from tugging a bale of hay from a tall stack. “Horses like to have friends around when they’re in the stalls.”

“I bet they try to squash the cats flat, just for fun.”

The cats have followed close at her heels. Shiloh bends down and pokes at the gray one with her finger. The cat pushes back, trying to get Shiloh to pet him. Now the other one wants to be petted too.

“You’d be surprised,” the woman says. “Horses tend to know how strong they are, how big. They’re pretty gentle around small creatures. They like cats. I’ve found the gray one — Jasper — lying right across Mercer Rex’s back, taking a snooze.”

“I bet Night would squash them flat.”

Another cat, all white with blue eyes and a gray tail, darts out from behind the hay. Shiloh stands up. She doesn’t have to pet the stupid cats if she doesn’t want to.

“What I do is break the bale into two parts,” Mrs. Lima Bean is saying. “Like this.”

Shiloh watches as the woman takes a knife out from her back pocket and snips the twine that’s holding the hay together.

“You carry a knife?” Shiloh asks, and then bites her lip. She doesn’t want the woman to think that anything she does is cool or interesting in any way.

“It was my father’s,” the woman says. She flips the blade back in place and holds it out. “You can look at it, if you like. If you keep it closed.”

Shiloh doesn’t want to be treated like a baby, told what to do. But she goes forward anyway, and takes the knife and holds it in her hand.

The knife is brown and silver, solid, with a horse engraved on one side and hutch engraved on the other. Shiloh thinks about clicking open the blade just to prove to the woman that she can do what she wants.

“Lincoln Andrew Hutchison,” the woman says. “That was my father’s name. But people called him Hutch.”

So?

That’s what Shiloh wants to say, but she doesn’t. “My dad was in the army,” she says instead. “My real dad. Not my mom’s boyfriend. My real dad was brave, and he probably had a lot of knives. And guns, too. He left before I was born. He didn’t like being pinned down.”

“I’m sorry, Shiloh.”

“I don’t care!” Shiloh doesn’t want the woman’s pity. “I didn’t know him.” She could put the knife into her pocket, if she wanted, just to see what the woman would do, but she goes ahead and hands it back.

“I’ve been giving Night half a bale in the morning, and half in the evening —”

“I’m probably not going to do this every day,” Shiloh interrupts.

“That’s okay. I know Night appreciates it.” The woman grins sideways at her. “He doesn’t scream at you so much.”

“He doesn’t scream at me at all!”

Mrs. Lima Bean keeps grinning, like a dummy.

“There are a couple of wheelbarrows over there,” she says, nodding toward the corner. “You can use one to carry the hay out to the field.”

Shiloh takes a look. One of the wheelbarrows has brown stuff in it. “Is that what I think it is?” She scrunches up her face. “Gross.”

The woman laughs. “I was just about to take that load out to the compost. You can use the other wheelbarrow for the hay.”

“That stuff stinks.” Putting a hand over her nose.

“I’ve never minded the smell too much,” Mrs. Lima Bean says. “In fact, I think it smells kind of good.”

Shiloh stares at her. She is crazy.

“That’s just plain gross.”

“Horses are herbivores.”

Shiloh rolls her eyes. She hates when Mrs. Lima Bean acts like she’s so smart.

“Herbivores only eat grass and grains. So that’s what their manure smells like.”

“I don’t want to know what their poop smells like!”

Mrs. Lima Bean laughs again, and Shiloh wants to kick her. She could just leave if she wanted to and forget about the stupid hay.

“I’ll take this on out,” the woman says, heading for the wheelbarrow. “You can get the hay for Night if you want.”

Shiloh hesitates. But then she stalks over and grabs hold of the handle. The wheelbarrow is heavier than it looks. It takes a couple of tries before she can roll it straight over to the stacks of hay.

“Don’t get used to this,” Shiloh calls after the woman. “Just because I’m getting the hay doesn’t mean I’m going to start helping you with the gross stuff.”

But Mrs. Lima Bean has already disappeared out of the mouth of the barn.

Shiloh clicks her tongue. She’ll have to tell her later. She’ll have to make sure she understands.

It’s a one time thing. Maybe two. At the most. She’ll give the black horse some hay today. But who’s to say she’ll do it again tomorrow? Maybe she’ll be gone by then.

Two

JESSALYNN

The sun is shining bright and cheerful through the window when the woman opens her eyes. She can feel it instantly. The stiffness is gone. The rain has cleared.

“Lazybones,” she mutters to herself when she sees the clock. “Why didn’t you wake me up, huh?” She gives Bella a gentle nudge.

Downstairs, Jess rinses out the coffeepot. No dirty cereal bowl in the sink. No sign of Shiloh out the window.

Jess listens for sounds overhead. Nothing. And so while the coffee is perking, she heads back up the stairs. She stands at the closed door to Shiloh’s bedroom, taps softly, and then harder.

No response, and so she eases the door open just a crack.

The girl is lying with the quilt pulled all the way up despite the sunny warmth of the room. Only the pale strands of her hair are showing.

“Shiloh?”

The girl doesn’t move, doesn’t respond.

Did she have a nightmare? One that Jess didn’t hear? Was she frightened and awake in the middle of the night?

Jess takes a step into the room. The girl shifts under the quilt, but doesn’t wake.

Strange how they both slept late today. But then again, maybe they both needed it. So many restless nights.

Jess turns and pulls the door closed behind her. Back downstairs she drinks her cup of black coffee and heads out toward the barn. She can hear the horses calling to her, asking what’s taken her so long.

SHILOH

She listens to the woman’s footsteps, later than usual, heading down to the kitchen. And then coming back up again. She pulls the covers over her head when she hears the knock, the woman calling her name. She acts like she’s sleeping when the woman opens the door.

After the woman is gone, Shiloh sits up. And then she’s watching the same old thing. The woman walking outside with the dog, disappearing into the barn.

She was starting to like it. The same thing every morning. A routine.

But now just watching the woman and the dog makes her mad.

How can somebody do the same thing day after day? Over and over again?

It’s good she’s leaving. She won’t miss anything about this place.

Except.

She looks past the barn, toward the far field. The black horse is just now leaving his corner, walking to the gate, slow and careful like the woman.

When he gets to the gate, he lifts his head and sniffs at the air. He turns toward the house, ears all the way up, listening.

Is he waiting for her?

No, that’s stupid. He’s just a horse. He’s hungry, that’s all. He wants his bucket of food. It doesn’t matter who brings it to him.

“Not today, buddy.” Shiloh makes her voice hard. “Not from me.”

She turns away from the window. She ignores the feeling in her chest. She doesn’t even know what it means.

• • •

NIGHT

The sun rises, and the child is not there, and it doesn’t matter.

He tells himself.

It does not. Matter.

When the woman finally walks over with the bucket of warm mash, he rushes at her. He won’t let her hook the feed over the gate. He kicks at the metal. He screams. He snaps his teeth at her.

And then he goes back to his corner.

He will not turn. Even if he hears the child’s footsteps on the gravel.

He will not turn. And he will not let her touch him again.

© 2010 Heather Henson

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (May 4, 2010)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416948995

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 470 The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Raves and Reviews

Three lives and three story lines merge as readers get to know a former racehorse, a 12-year-old girl, and a middle-aged woman. Dream of Night was a successful Thoroughbred until an undetected injury led, over time, to horrific abuse and neglect. Shiloh and her mom suffered unspeakable domestic violence, landing Shiloh in increasingly ineffective foster homes. Jess has spent years working with rescued horses and foster kids, but thinks that perhaps she is too old now for either one. Night and Shiloh both end up at Jess’s farm and are needy, angry, and incapable of trust. Eventually, cracks begin to appear in the walls that the two have erected, and a crisis cements their bond. Within each chapter, the third-person narration switches from character to character, with each portion labeled. The brief sections use few words to maximum potential, developing each character and focusing on believable behaviors. While accepting Night’s line of thought occasionally requires a leap of faith, this is a touching read with a satisfying ending. Recommend it to kids who have heard about Dave Pelzer’s A Child Called “It” (Health Communications, 1995) and to animal lovers or girls who read reluctantly.–SLJ, April 1, 2010

Once Dream of Night was a champion racehorse, but by the time Jess DiLima gets him he’s nearly dead from starvation and pneumonia, and his thin hide is covered in scars. Twelve-year-old Shiloh is scarred, too, both from physical abuse and from the emotional withering of years in foster care. Jess doesn’t feel up to the challenge of either one of them, but she knows that she may represent their last chance. Henson’s story unfolds in a tight, third-person, present-tense narration that shifts its focus among the three principals: Jess, Shiloh and Night. Her novel, like her characters, shimmers with anger and hope. She doesn’t pull her punches—the scenes and flashbacks of abuse are realistically graphic—but she also never lets the details overwhelm the narrative, always offering the possibility of redemption. The author understands, too, that victory is not necessarily a blue ribbon won or a family reunited—sometimes it’s just the quiet triumph of a girl confidently brushing a horse in a stall. Another impressive book by the author of Here’s How I See It—Here’s How It Is (2009). -- KIRKUS, April 15, 2010

Awards and Honors

- Dorothy Canfield Fisher Book Award Master List (VT)

- Black-Eyed Susan Book Award Nominee (MD)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Dream of Night Hardcover 9781416948995(2.4 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Heather Henson Photograph by Kirk Schlea(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit