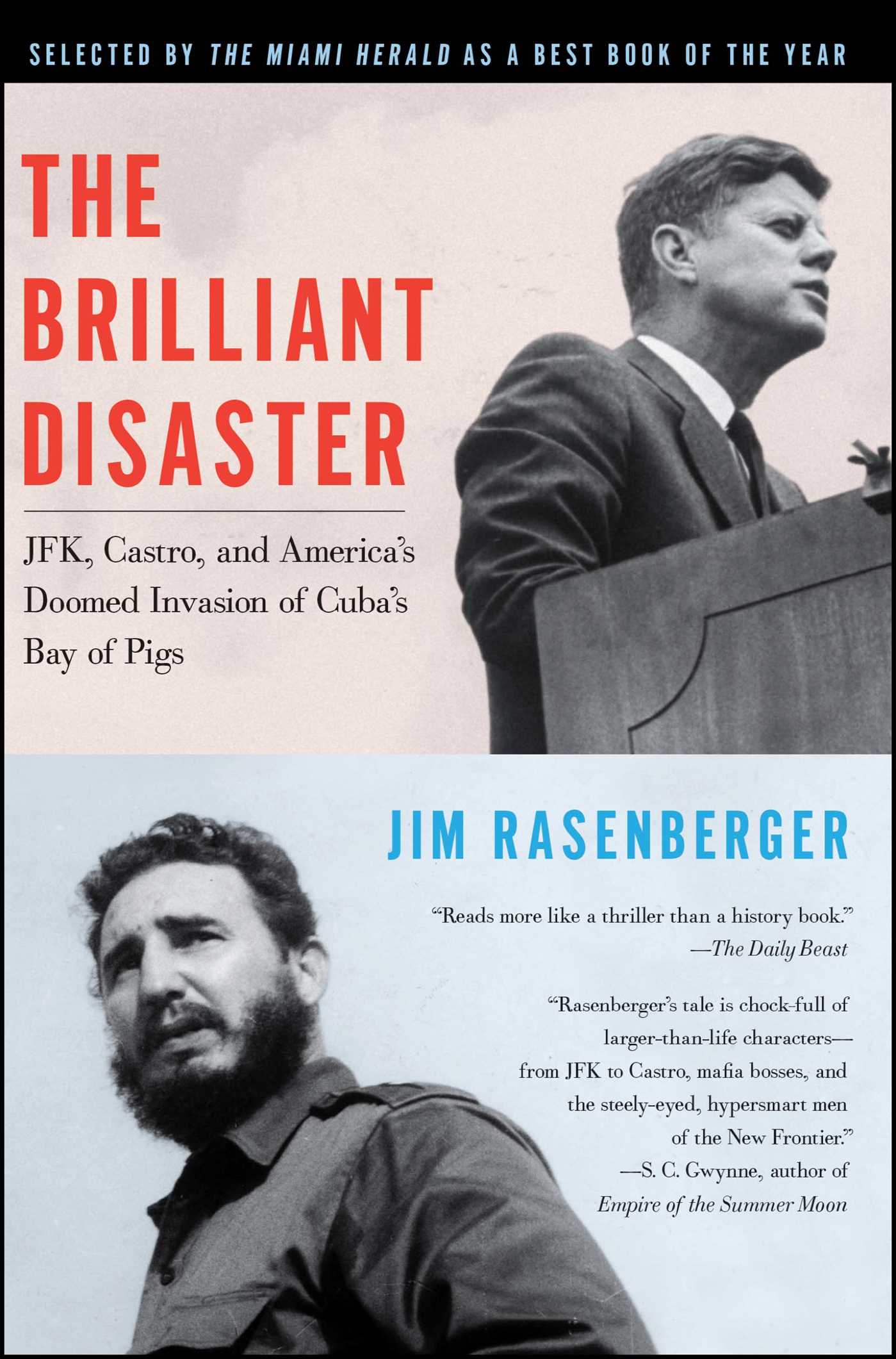

The Brilliant Disaster

JFK, Castro, and America's Doomed Invasion of Cuba's Bay of Pigs

Table of Contents

About The Book

At the heart of the Bay of Pigs crisis stood President John F. Kennedy, and journalist Jim Rasenberger traces what Kennedy knew, thought, and said as events unfolded. He examines whether Kennedy was manipulated by the CIA into approving a plan that would ultimately involve the American military. He also draws compelling portraits of the other figures who played key roles in the drama: Fidel Castro, who shortly after achieving power visited New York City and was cheered by thousands (just months before the United States began plotting his demise); Dwight Eisenhower, who originally ordered the secret program, then later disavowed it; Allen Dulles, the CIA director who may have told Kennedy about the plan before he was elected president (or so Richard Nixon suspected); and Richard Bissell, the famously brilliant “deus ex machina” who ran the operation for the CIA—and took the blame when it failed. Beyond the short-term fallout, Rasenberger demonstrates, the Bay of Pigs gave rise to further and greater woes, including the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and even, possibly, the assassination of John Kennedy.

Written with elegant clarity and narrative verve, The Brilliant Disaster is the most complete account of this event to date, providing not only a fast-paced chronicle of the disaster but an analysis of how it occurred—a question as relevant today as then—and how it profoundly altered the course of modern American history.

Excerpt

“The Bay of Pigs Thing”

BACK IN THE first half of the twentieth century, America was a good and determined nation led by competent men and defended by an indomitable military—that, anyway, was a plausible view for Americans to hold fifty years ago. The First World War, then the Second World War, asserted and confirmed America’s place of might and right in the world. Even in the decade after the Second World War, as a new conflict in Korea suggested there were limits to what the United States might accomplish abroad, it would have been a cynical American who doubted he or she lived in a powerful nation engaged in worthy exploits.

And then came the Bay of Pigs.

In the early hours of April 17, 1961, some fourteen hundred men, most of them Cuban exiles, attempted to invade their homeland and overthrow Fidel Castro. The invasion at the Bahía de Cochinos—the Bay of Pigs—quickly unraveled. Three days after landing, the exile force was routed and sent fleeing to the sea or the swamps, where the survivors were soon captured by Castro’s army. Despite the Kennedy administration’s initial insistence that the United States had nothing to do with the invasion, the world immediately understood that the entire operation had been organized and funded by the U.S. government. The invaders had been trained by CIA officers and supplied with American equipment, and the plan had been approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the president of the United States. In short, the Bay of Pigs had been a U.S. operation, and its failure—“a perfect failure,” historian Theodore Draper called it—was a distinctly American embarrassment. Bad enough the government had been caught bullying and prevaricating; much worse, the United States had allowed itself to be humiliated by a nation of 7 million inhabitants (compared to the United States’ 180 million) and smaller than the state of Pennsylvania. The greatest American defeat since the War of 1812, one American general called it. Others were less generous. Everyone agreed on this: it was a mistake Americans would never repeat and a lesson they would never forget.

They were wrong on both counts.

Mention the Bay of Pigs to a college-educated adult American under the age of, say, fifty and you are likely to be met by tentative nods of recognition. The incident still rings discordant bells somewhere in the back of our national memory—something to do with Cuba, with Kennedy, with disaster. That phantasmagorical phrase alone—Bay of Pigs—is hard to forget, evoking images of bobbing swine in a bloodred sea (or at least it did in my mind when I first heard it). But what exactly happened at the Bay of Pigs? Many of us are no longer certain, including some of us who probably ought to be. At about the time I began thinking about this book, Dana Perino, the White House press secretary for President George W. Bush, good-naturedly confessed on a radio program that she confused “the Bay of Pigs thing” (April 1961) with the Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962). Given that Ms. Perino was born a decade after these events, her uncertainty was understandable. But coming from the woman representing the president who launched the invasion of Iraq in 2003—an exercise that repeated some of the very same mistakes made in Cuba in 1961—it also was unsettling. Presumably, somebody in the Bush White House considered the history of the Bay of Pigs before sending Colin Powell to the Security Council of the United Nations (an episode, as we shall see, bearing striking similarities to Adlai Stevenson’s appearance before that same body in April 1961) or ordering a minimal force to conquer a supposedly welcoming foreign land.

Then again, if history teaches us any lesson, it is that we do not learn the lessons of history very well. Almost as soon as the mistakes of the Bay of Pigs were cataloged and analyzed by various investigative bodies, America began committing them again, not only in Cuba, but elsewhere in Latin America, in Southeast Asia, in the Middle East, in Africa. By one count, the United States has forcibly intervened, covertly or overtly, in no fewer than twenty-four foreign countries since 1961, not including our more recent twenty-first-century entanglements in Iraq and Afghanistan. Some of these have arguably produced long-term benefits for the United States. Most clearly have not.

The surfeit of interventions gives rise to a fair question: considering all that has occurred since 1961, why should the Bay of Pigs still demand our attention? Next to Vietnam and Iraq, among others, the Bay of Pigs may seem a bump in the road fading mercifully in the rearview mirror. The entire event lasted a mere five days and cost the United States roughly $46 million, less than the average budget of a Hollywood movie these days. One hundred and fourteen men were killed on the American side, and only a handful of these casualties were U.S. citizens. Add to this the fact that America was embarrassed by the Bay of Pigs and the tale has everything to recommend it for oblivion.

Even if we would forget the Bay of Pigs, though, it will not forget us. There among the mangrove swamps and the coral-jeweled waters, some part of the American story ended and a new one began. Like a well-crafted prologue, the Bay of Pigs sounded the themes, foreshadowed the conflicts, and laid the groundwork for the decades to follow. And what followed was, in no small measure, a consequence of the events in Cuba in 1961. It would be facile to credit the 1960s to a single failed invasion—many currents combined to produce that tsunami—but the Bay of Pigs dragged America into the new decade and stalked it for years to come. Three of the major American cataclysms of the ’60s and early ’70s—John Kennedy’s assassination, the Vietnam War, and Watergate—were related by concatenation to the Bay of Pigs. No fewer than four presidents were touched by it, from Dwight Eisenhower, who first approved the “Program of Covert Action” against Castro, to Richard Nixon and the six infamous justice-obstructing words he uttered in 1972: “the whole Bay of Pigs thing.”

MY TELLING OF the Bay of Pigs thing will certainly not be the first. On the contrary, thousands of pages of official reports, journalism, memoir, and scholarship have been devoted to the invasion, including at least two exceptional books: Haynes Johnson’s emotionally charged account published in 1964 and Peter Wyden’s deeply reported account from 1979. This book owes a debt to both of those, and to many others, as well as to thousands of pages of once-classified documents that have become available over the past fifteen years, thanks in part to the efforts of the National Security Archives, an organization affiliated with George Washington University that seeks to declassify and publish government files. These newer sources, including a CIA inspector general’s report, written shortly after the invasion and hidden away in a vault for decades, and a once-secret CIA history compiled in the 1970s, add depth and clarity to our understanding of the event and of the men who planned it and took part in it.

If what follows is not quite a story never told, it may be, even for those well acquainted with the event—especially those, perhaps—a different story than the one readers thought they knew. Because the Bay of Pigs was so cataclysmic and personally anguishing to so many involved, and because it raised questions about core American values, its postmortems have tended to be of the finger-pointing, ax-grinding, high-dudgeon variety. This includes personal memoirs and reminiscences, but also serious and measured works such as Johnson’s and Wyden’s, both of which were colored by the circumstances under which they were written. Johnson’s book, published just a few years after the invasion, was authored with heavy input from leaders of the Cuban exile brigade and is raw with their pain and resentment. Wyden’s book was written in the late 1970s, following Watergate and an inflammatory Senate investigation into CIA-sponsored assassinations (the so-called Church Committee), when national outrage for government subterfuge was at a high point and esteem for the CIA hit new lows. The book announces its bias on the very first page, when Wyden describes the CIA as “acting out of control” during the Bay of Pigs. Many other books, articles, and interviews have added to the riot of perspective: those by Kennedy partisans who damn the CIA; those by CIA participants who damn Kennedy; those by Cuban exiles who damn both, and Castro, too; and those by Cuban nationals who hail the events of 1961 as a great defeat of American imperialism and a defining episode in the hagiography of Fidel Castro.

With the possible exception of Castro, no one came out of the Cuban venture smelling sweet, but over time the CIA came to assume the rankest odor of all. Starting with the publication of two important memoirs by senior Kennedy aides in the fall of 1965—Arthur M. Schlesinger’s A Thousand Days and Theodore Sorensen’s Kennedy—a steady stream of books championed the view that John Kennedy was a victim in the Bay of Pigs, and especially a victim of the CIA’s arrogance and malfeasance. Several recently published books that treat the Bay of Pigs suggest this view has won out and is now conventional wisdom. One recent bestseller, David Talbot’s Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years(2007), describes a defiant CIA driven by “cynical calculation” while engaged in an effort to “sandbag” President Kennedy with the Bay of Pigs. Another, Tim Weiner’s history of the CIA, Legacy of Ashes (2007), portrays an agency that managed to combine duplicity with dereliction, somehow running circles around Kennedy and his advisers even as it tripped over its own two feet.

The more complicated truth about the Bay of Pigs is that it was not ginned up by a nefarious band of agents in the bowels of the CIA, but rather produced by two administrations, encouraged by countless informed legislators, and approved by numerous men of high rank and intelligence, even brilliance, who either did know, or should have known, what they were agreeing to. As for why they did this—“How could I have been so stupid?” is how Kennedy phrased the question—the answer is that all of them, from the presidents to the Central Intelligence Agency, from the Pentagon to the State Department, were operating under conditions that made the venture almost impossible to resist. At a time when Americans were nearly hysterical about the spread of communism, they simply could not abide Castro. He had to go. And the CIA, in 1960, was the tool Eisenhower, then Kennedy, intended to use to speed him on his way.

Unsettling as it may be to conjure a “rogue elephant,” as the CIA was often described after the Bay of Pigs, making and executing lethal and boneheaded foreign policy on its own, more troubling may be the possibility that the Bay of Pigs—or any number of subsequent disasters abroad—was driven by irrational forces and fears in the broad American public, and that its pursuit and failure reflected not one man’s or one group’s moral or intellectual failings, but the limits of a democratic government’s ability to respond sensibly to frightening circumstances. By the time the Bay of Pigs occurred, it almost was rational—a logical conclusion arrived at from a set of premises that were, in 1961, practically beyond question. Clearly the CIA chose the wrong way to go about unseating Castro, but really, is there any good way to overthrow the government of a sovereign nation?

My goal in these pages is not to defend the CIA, or anyone else, but to treat the participants with more empathy than prejudice, the better to understand their motives. As a litany of misdeeds, the Bay of Pigs is dark comedy; only when we consider it in the full context of its time does it reveal itself, instead, as Greek tragedy. Not all participants in the affair behaved well, but of the many extraordinary facts about the Bay of Pigs, the most surprising may be that it was the work of mostly decent and intelligent people trying their best to perform what they considered to be the necessary emergency procedure of excising Fidel Castro. With a few notable exceptions—Senator William Fulbright was one—it never occurred to any of them that America could tolerate Fidel Castro’s reign. Certainly it never occurred to them that Castro’s reign would outlast the administrations of ten U.S. presidents.

IN SOME WAYS, this is a tale from the distant past. Other than the frozen state of relations between the United States and Cuba, virtually unchanged since 1961, we live in a world that is very different from the one that produced the Bay of Pigs. The Cold War is over; the War on Terror has taken its place as our national bête noire. Fidel Castro, in retrospect, seems a benign threat next to the likes of Osama bin Laden. But America is still driven by the same conflicting motives and urgencies that landed the country at the Bay of Pigs fifty years ago. On the one hand, we are a people convinced of our own righteousness, power, and genius—a conviction that compels us to cure what ails the world. On the other hand, we are stalked by deep insecurities: our way of life is in constant jeopardy; our enemies are implacable and closing in. This paradox of American psychology was apparent well before the Bay of Pigs—Fidel Castro pointed it out to Richard Nixon in 1959, as we will see in this book’s first chapter—but compounding it after 1961 were new concerns about the limits of American power, not to mention the limits of American competence and morality. The days of the “splendid little war,” as Ambassador John Hays famously called the United States’ military venture in Cuba in 1898 (during the Spanish-American War), are long gone now. Instead, we get complicated, tormented affairs that never seem to end. In this respect, at least, the Kennedy administration earned this book’s otherwise oxymoronic title, and without irony: their disaster was brilliantly brief. It could have been far worse, as a number of very smart people noted afterward. What does it tell us that some of those same smart people—“the best and the brightest,” author David Halberstam indelibly tagged them—later engineered America’s descent into Vietnam? Irony never strays far from this tale.

We are still trying to come up with the solution to the conundrum that gave rise to the Bay of Pigs: how to use American power to make the world to our liking, but do so in a manner that holds true to the values we espouse. One piece of evidence that we have not quite figured this out can be found, coincidentally, on the eastern tip of Cuba, where the United States still holds prisoners from the War on Terror at Guantánamo. What to do about this and similar matters remains the problem of our current president, Barack Obama, born in August 1961, a few months after the Bay of Pigs.

As it happens, my own life began just after the Bay of Pigs and was soon touched by it, albeit obliquely. In December 1962—when I was a few months old—my father was briefly but significantly involved in the episode’s dramatic finale. A young and politically involved lawyer at the time (he’d done advance work for John Kennedy), he was recruited to join Robert Kennedy’s pre-Christmas effort to bring home more than a thousand men who had been taken prisoner by Fidel Castro during the Bay of Pigs. For an intense few weeks leading up to Christmas 1962, my father and several other private attorneys, as well as men from the attorney general’s office such as Louis Oberdorfer and Nicholas Katzenbach, virtually lived at the Justice Department as they worked to secure the prisoners’ release. My father’s role was small, and came only near the end. I mention him here to point out that I grew up more attuned than most to the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and yet I can’t say my understanding of it was at all clear. I suspect that to most people around my age, the Bay of Pigs is an incident of the dim, dark past, like a childhood memory of something not meant for children’s eyes. Meanwhile, for older Americans—those of my father’s generation—it’s a memory that is fading.

Not so in Cuba, as I learned when I visited the island in the spring of 2010, on the invasion’s forty-ninth anniversary. To Cubans, the Bay of Pigs episode is known simply as “Girón,” after the beach where the invasion began and ended, and the Cuban victory there is one of the founding mythologies of modern Cuba. Schoolchildren learn of it when they are young and are never allowed to forget. Every April, billboards throughout Havana herald it anew, and Playa Girón becomes a kind of mecca for invasion tourists and government officials. Passing a giant billboard that announces Girón as the site of the PRIMERA DERROTA DEL IMPERIALISMO YANQUI EN AMERICA LATINA (First Defeat of Yankee Imperialism in Latin America), busloads of schoolchildren and military personnel arrive at the small seaside hamlet. They visit the battle museum, poke into the shops, and walk down to the palm-shaded beach where the “mercenaries” first landed. Local laborers slap a fresh coat of white paint onto the base of the telephone poles and line the main road into town with palm fronds, sprucing up for the dignitaries who will arrive from Havana on April 19 and stand on a platform in front of the Hotel Playa Girón to declare the victory all over again.

Meanwhile, at the western end of the beach where the invasion occurred, two military sentries stand atop an old shack that has been turned into a military post. Day and night, they look out to sea with high-powered optical equipment, searching, waiting, as if expecting, any moment, an invasion force to arrive all over again.

© 2011 Jim Rasenberger

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (April 10, 2012)

- Length: 480 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416596530

Raves and Reviews

“This is history at its best: meticulous research distilled into luminous prose and a gripping narrative. This is not only the finest book ever written on the Bay of Pigs fiasco, but also one of the most balanced, keen-eyed surveys of the early days of the Kennedy administration. A page-turner that packs as much of a punch as the best of fiction thrillers, Rasenberger’s The Brilliant Disaster lays bare many a bleached bone, but, in the process, also provides readers with invaluable treasure: a clearer understanding of the relation between past, present, and future.” —Carlos Eire, National Book Award winning author of Waiting for Snow in Havana

“This is history at its best: meticulous research distilled into luminous prose and a gripping narrative. This is not only the finest book ever written on the Bay of Pigs fiasco, but also one of the most balanced, keen-eyed surveys of the early days of the Kennedy administration. A page-turner that packs as much of a punch as the best of fiction thrillers, Rasenberger’s The Brilliant Disaster lays bare many a bleached bone, but, in the process, also provides readers with invaluable treasure: a clearer understanding of the relation between past, present, and future.” —Carlos Eire, National Book Award winning author of Waiting for Snow in Havana

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Brilliant Disaster Trade Paperback 9781416596530

- Author Photo (jpg): Jim Rasenberger Photograph by Jackson Rasenberger(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit