Crazy Good

The True Story of Dan Patch, the Most Famous Horse in America

Table of Contents

About The Book

• A great underdog story: Born with a bad leg and nearly destroyed at birth in 1896, Dan Patch became the greatest champion racehorse of his day, lowering the record for the mile by four seconds, an astounding achievement that stood for decades. Put to work pulling a wagon, he was entered in a race as a lark, but won it—and never lost throughout his long career.

• A bygone American era: Crazy Good is the story of America in simpler times, when the automobile was a novelty and most people preferred horses; an era when horse racing— pacers and trotters—was a dominant sport of the day.

• Colorful writing, colorful characters: Leerhsen populates his story with great characters, from the entrepreneur owner who made Dan Patch into a household name, to the alcoholic gambler who drove the horse to his greatest victories.

Excerpt

The 1900s was an age of Charisma, and some of the healthiest personalities, those with a natural endowment of the stuff, radiated their own heat—a few seemed like walking planets. They had a gravitational heft that had nothing to do with physical size.

—Darin Strauss, The Real McCoy

THE CROWD ROSE AS one to stare at the horse, and the horse, as was his custom, stared back.

It was 4:35 p.m. on October 7, 1905, a brilliant fall Thursday at the Breeders Track in Lexington, Kentucky, and Dan Patch, a big mahogany-brown stallion, had just finished an attempt to lower his own world record for the mile. He was still blowing hard, but after wheeling around and jogging back to the finish line—on his own, with no guidance or encouragement from the small, mustachioed man sitting in the racing sulky behind him—he had come to a dead stop and, with his head cocked slightly to the left, was slowly and deliberately surveying the assembled.

This was a trademark move, something he did not do automatically, like a circus animal mindlessly performing a trick, but often enough, when the mood struck. People waited for it, and felt like they had gotten their money’s worth when it came. Dan Patch’s fans used to say—when they talked about him in taverns and barbershops and at dinner tables all over America—that the horse liked to count the house.

A dramatic silence fell over the scene. An official clocking would come down from the judges at any moment, and a quarter of a second either way could mean the difference between the front page and the sports section. Had Dan done the impossible once again? In the press area, a finger hovered above a telegraph key.

From where the horse stood, he could hear the three timers in the judges’ stand, a few feet behind and about twenty feet above him, murmuring confidentially as they consulted their chronographs; if their individual hand-timings differed, as they might easily by a fraction of a second or so, they needed to reach a consensus on an official clocking. In an age when horse speed, and the mile record in particular, mattered to a mass audience, these racing judges were men of gravitas, doing important work. They wore suits and ties and natty straw boaters. They hefted 17-jewel stopwatches that had the power to transform a day at the races into an historic event. If Dan Patch had gone as fast as some in the packed grandstand guessed he had, everyone there would have a story to tell, maybe for the rest of his life. Tens of thousands who weren’t there would also claim to have seen the beautiful brown horse power down the homestretch of the perfectly manicured red-clay racetrack in the lengthening autumn shadows. It was a golden age of sports, horses, ladies’ hats, and bullshit.

Seconds ticked by, tension increased, but the horse, as a reporter said later, was the calmest person on the grounds. Nine years old and at his physical peak, Dan Patch stood at almost the exact midpoint of a long career spent, for the most part, touring the country in a plush private railroad car and putting on exhibitions of speed. He knew the drill: first there was the Effort, the race against the clock, one mile in distance, with the galloping prompters to urge him on and stir his competitive spirit. Then there was the Silence, as judges checked their watches. After the Silence came either the Roar—a world record!—or the Sigh—alas, not this time. The Roar invariably involved flying hats and a surging wave of well-wishers.

Dan Patch preferred the Roar. Which was odd, because why would a horse choose hysteria over a quiet walk back to the barn? What did he care about world records and the endless hype? The preference wasn’t horselike. Dan Patch was an odd horse.

He was different to a degree, in fact, that experienced horse handlers found amazing, even hateful (jealousy being a big part of the racing game). For example, though stallions tend to be skittish, lashing out with teeth and hooves at the slightest provocation, Dan Patch—an intact male who had already shown he had no problems in the breeding shed—exuded calm, allowing strangers to approach him and small children to run back and forth beneath his belly. He wasn’t frightened by the world human beings had made. He did not waste energy worrying, or see danger where there wasn’t any, or fret about things he could not change. He trusted—a quality humans found terribly flattering, and loved him for. As for the racing and touring, he seemed to get it, to understand that his job was to be this new thing in America: a superstar. Whenever he saw a photographer, he stopped.

That evening in Lexington, Dan Patch would be led into the lobby of the Phoenix Hotel, where happy drunks would pat his nose and perfumed women would want to nuzzle. Whatever he was thinking when people pressed around him, Dan remained charming and affable; the boors and the rubes always went away feeling noticed and cared-for. Fans sometimes pulled hairs from his tail to twist into key chains or put into lockets; in such cases, Dan might spin his handsome head around and cast a sharp glance, but he never kicked. He had an admirable sense of his own might, and others’ vulnerability. The only person Dan Patch ever bit was a young Minnesota boy named Fred Sasse, who would grow up to write an appallingly bad book about him. You just had to love a horse like this.

And people did. They turned out to see him, 80,000, 90,000, 100,000 strong, paying usually a one-dollar admission, a day’s wage for the average Edwardian Joe. Sometimes when Dan would amble out, unannounced, for a few warm-up laps, hours before he was scheduled to race, the crowd would erupt in a sustained huzzah that would not subside until he headed off twenty minutes later—sometimes but not always taking a little bow at the top of the exit ramp, stirring up his fans even further. Teddy Roosevelt, the president during Dan Patch’s prime, bragged about having a Dan Patch horseshoe at his home in Oyster Bay, Long Island (“A gift from his owner—from the race in which he broke the two-minute mile!”). The actress and courtesan Lillie Langtry visited Dan in his gleaming-white custom-built railroad car with his almost-life-size picture emblazoned across both sides; as famous as the Jersey Lily was (mostly for being the mistress of both Edward VII and his nephew, Louis of Battenberg), the meeting clearly meant more for her career than his.

On days when the horse wasn’t performing, people would wait in line for hours just to see him standing in his stall, sometimes looking less than regal with his pet rat terrier perched atop his head. Dwight Eisenhower recalled queuing up with his parents to see Dan at the Kansas State Fair in 1904; Harry Truman, in his postpresidential dotage, remembered sending Dan a fan letter.

People exaggerated their connection to the horse to make themselves seem more important, or better human beings. A common boast in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s—a kind of urban myth comparable to saying you were at Wrigley Field when Babe Ruth hit his famous “called shot” home run—was to say you were once at a racetrack someplace, leaning on the fence and watching Dan Patch warm up, when his trainer drove the horse over, picked you out of the crowd, and asked if you’d like to take ole Danny boy for a spin. The story, which was told all over the country, had two seemingly contradictory points: that Dan, like Jesus, moved among the common folk, and that you were somebody special for being picked to drive him. (Some said they jumped at the chance to sit behind him in the sulky; others, unwilling to weave a more tangled web, claimed to have demurred.) In their obituaries, many who had never met Dan Patch—or who had perhaps only the slightest connection, having mucked out the stall next to his at a state fair one morning, say—were identified as his trainer, owner, breeder, horseshoer, or groom, their impressive fibs following them relentlessly to the grave. So many people lied about having groomed the horse that one Dan Patch Web site lists as a FAQ, “How can I verify that my relative was Dan Patch’s caretaker?” (The answer: You can’t, because the poor soul almost certainly wasn’t.) In 1923 an early author of self-help manuals, Harry Heffner, published a pamphlet called Dan Patch: The Story of a Winner, in which he revealed how to become a more highly effective businessperson, friend, spouse, and Christian by acquiring the virtues of the by-then-deceased horse. In the introduction to a book called The Autobiography of Dan Patch, written by a publicist named Merton E. Harrison and published in 1911, the author writes, “The work of his caretakers, trainers and drivers has always been high class, but it has always been supplemented by the self-esteem, the care and thoughtfulness of the horse himself. Dan Patch has come to be spoken of as ‘the horse that knows.’”

Even John Hervey, the preeminent turf writer of the early twentieth century, a florid scribe at times but usually a sober one, fell hard for the horse. “A kinder, a wiser, a finer dispositioned spirit in equine form never lived,” Hervey wrote of Dan in the 1930s. “He was goodness personified. And wisdom. That he knew more than most of the men then on earth was the firm conviction of those who knew him. It was almost unbelievable that a horse with so mighty a heart, so dauntless a courage, such endless masculine resolution, strength and power, could at the same time be so mild, so docile, teachable, controllable, lovable. Those constantly with him worshipped him—would have died for him, I veritably believe, had it been necessary.”

In this one animal, humbly bred and congenitally malformed, had come together all the virtues the horse-drawn world had ever imagined. To use the parlance of the day, Dan was crazy good. Dan Patch madness was still approaching its peak that day in October of 1905, when the horse, with tremendous fanfare (which is to say, the usual fanfare), came to Lexington. The local hardware store by then might have a Dan Patch calendar hanging on its wall, and anyone could buy Dan Patch cigars and sleds from stores and mail-order catalogs, but the great wave of Dan Patch merchandise, the washing machines, breakfast cereals, rocking horses, dinner plates, pocket watches, pocketknives, pancake syrup, automobiles—even Dan Patch real estate and the Dan Patch stallion shield, to prevent the family carriage horse from masturbating—all these fine products and more had yet to hit the marketplace. Further in the future, too, was a certain morbidly cold, rainy day in Los Angeles, when the track was slippery, the crowd was thin, and the party was long past over.

At Lexington in 1905, though, life was good, and the rose was still blooming. Dan Patch, that day, was all about hope and promise and a possible payoff in the betting for those who had wagered, at even money, that he would beat his famous world record for the mile.

At last, a man in the judges’ stand stood up and lifted a megaphone to his lips.

In the grandstand, women leaned forward clutching the souvenir Dan Patch horseshoes that their husbands and beaux had bought them for a dollar on the way in. Men leaned forward too, and touched the brims of their straw boaters, aware that hats might have to be flung.

Dan Patch stopped panting and pricked up his ears.

“The time for the mile . . . ,” said the judge, and then he shouted the numbers, declaiming them clearly in the direction of the crowd. But for once there was neither the Roar nor the Sigh. There was only more silence. The crowd seemed not to believe what it had heard.

The judge, bemused, lowered his megaphone and waited five or six heartbeats. Then he raised it up and shouted the numbers again, hitting each one hard, until his voice rasped.

Silence, still, for another heartbeat.

And another.

Now came the Roar.

The events of this book may seem as if they transpired on another planet.

Harness horses have not made front-page headlines across the nation since fast food meant oysters. Racehorses of any ilk don’t linger in the mass media these days unless they have terribly cute names or sad stories involving shattered cannon bones or kids with cancer. The sports and pop cultural paradigms have shifted so radically in the interim that it is difficult to wrap one’s mind around the truth: this pacer was the most celebrated American sports figure in the first decade of the twentieth century, as popular in his day as any athlete who has ever lived.

Who even knows what a pacer is anymore?

Backward leaps the imagination trying to comprehend it all. America was already sports-mad when Dan Patch made his public debut at a little country fair in Indiana in 1900—but only boxing, baseball, and horse racing really mattered. The latter, which mattered most of all, was divided into two distinct, and deeply rivalrous, pastimes: Thoroughbred racing, in which horses run various distances carrying various weights, most famously for the roses each spring—and harness racing, in which they don’t run at all, but compete rather at either of two gaits, the trot or the pace, pulling a two-wheeled rig called a sulky, almost always at the distance of a mile, the weight of the passenger being of relatively small significance.

Before Dan Patch’s day, and dating back to colonial times, the Thoroughbreds were the closely watched breed; it was their major races that tentpoled the sports calendar (such as it was in the pre–Civil War years), their hard-charging champions whom the masses cheered; if you said “horse racing” before 1885 or so you meant the sport of kings, the galloper’s game. By the time of Dan’s death in 1916, the same rules applied: the Thoroughbred had reclaimed the throne, which he has retained into this inglorious era of 3,000-person “crowds” at Belmont Park; “racinos,” where people literally turn their backs to the horses while pumping quarters into video slot machines; and Yum Foods Presents the Kentucky Derby. America’s sports fans, let it be acknowledged, have clearly shown their overall preference for this handsome, hyper, powerful-yet-fragile breed that the English confected in the eighteenth century and still so steadfastly admire.

Yet between its two lengthy marriages to the Thoroughbred, America had a passionate fling with the light harness horse, or Standardbred, as he is more formally known. For the final fifteen years of the nineteenth century, and the first fifteen of the twentieth, it was him they clearly loved best, and they followed his sport—known generically as trotting, despite a plethora of pacers—more fervently than any other.

Trotting and pacing races highlighted hundreds of city, county, and state fairs during this period, and rich men paraded their prized harness horses down Manhattan’s Third Avenue every Sunday, rain or shine, sometimes competing in informal “speed brushes” for side bets—a cask of oysters, say, or maybe a case of wine, a Florodora girl, or dinner at Luchow’s; the “Sealskin Brigade,” the drooling masses called the rotund, mustachioed millionaires who sat behind the dappled bays and grays. In 1873, a group of Standardbred owners and breeders started the Grand Circuit, a traveling race meet for the best stock, a kind of movable major league. The first example of an American sport organizing itself into a business with published schedules and standardized rules—baseball’s National League would follow shortly—the “Roarin’ Grand” became an instant hit, stopping in New York, Buffalo, Chicago, Indianapolis, Lexington, Detroit, and other major cities where thousands packed the stands to watch the premier Standardbreds compete for purses of $1,500 to $5,000—serious ragtime-era cash. Newspapers reflected the burgeoning public interest, providing race results, reporting on the sale of harness horses and the birth of foals, and passing along gossip with a Standard-bred slant (“Kennedy is thinking of shipping his trotter Dorothy S., whom he named for his pretty sister-in-law, to the state fairgrounds. His wife will not accompany him on the journey”). The Thoroughbreds got attention, too, during this period, of course—just not half as much. “Thoroughbred racing settled individual differences between horses,” wrote the racing journalist Dwight Akers. “It no longer measured a leveling up of the breed,” the way harness racing did.

What made the phenomenon all the more remarkable is that harness horses, then and now, have a lot going against them as crowd-pleasers. For one thing, they are, generally speaking, less comely than their more finely featured and curvaceous Thoroughbred cousins. For another thing, they are, although able to carry their speed for long distances while going at a trot (a diagonal gait in which the right front moves with the left rear, then vice versa) the pace (think parallel: right front and rear move together, then left front and rear), not as fast. Even their name—“standard” as compared to “thorough”—seems to render them second-class citizens, unexceptional animals, though the standard in question is not a slight but refers rather to an impressive minimum speed (2:30 for the mile) that was required of the breed’s charter members.

The saving virtue that more than offset these considerable faults was that the Standardbred had a practical application; he was something more than what the Thoroughbred had become—more, that is, than merely a bettor’s plaything. He was—along with the incandescent lightbulb, the slot machine, the gramophone, the typewriter, and other wonders of the age—a life-changing American invention. A loose network of equinophiles in the eastern United States had set out, circa 1835, to produce the great American driving horse—and within three decades they had, to their own amazement, succeeded brilliantly, compounding the Standardbred, a completely new breed, out of equal parts Thoroughbred bloodstock, common farm nags, and dumb luck. Some of these horses trotted naturally at relatively high speed others preferred to pace, but they were in either case a perfect fit for the changing times, when a network of well-engineered roads began snaking across America and our great-great-grandfathers got more sophisticated and citified, climbing out of the saddle and into the driver’s seat. The world suddenly was a world on wheels—the mid-nineteenth-century racing historian Frank Forester thought it worth noting that five out of six people he passed on the road in those days were driving, not riding. “The pleasure or spring wagon,” Forester noted, “appeared in many carriage houses long before the piano supplanted the quilting frame in the parlor.” And, he added, “speed, which was formerly little regarded, is now an indispensable requirement in a good horse.” New types of well-sprung vehicles rolled from factories daily; Anthony Trollope, traveling through Rhode Island in 1861, commented on the “general smartness” of the carriages he observed. And what would a smart and stylish person hitch to his buggy, barouche, or coach (not to mention his cabriolet, randem, berlin, victoria, surrey, herdic, hansom, rockaway, cariole, britzka, tilbury, chaise, phaeton, sluggy, gharry, coupé, curricle, trap, growler, gig, dos-à-dos, landau, limber, brougham, vis-à-vis, or whim)? Why, never some lurching galloper, as handsome as he might be. No, you wanted a smooth-going gaited horse—a Standardbred—between your shafts.

The first official Standarbreds, registered in 1879, were considered minor miracles. “The Standard-bred light-harness horse,” wrote John Hervey in his classic 1947 work The American Trotter, “is America’s great contribution to the ranks of the world’s most valuable domestic animals . . . universally recognized as the only separate and distinct breed of light horses which has originated with the memories of persons now living.” Ralph Waldo Emerson, the sage of Concord, was spotted frequently at the harness racing track in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Ulysses S. Grant became an early enthusiast, buying and breeding trotters and, after he went broke, watching other peoples’ trotters and arguing bloodlines with his friends. The elder Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote a wildly popular poem called “The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay,” an ode to the kind of vehicle a Standardbred might pull, and an equally adored companion piece titled “How the Old Horse Won the Bet” that contained this couplet celebrating one of harness racing’s first star drivers:

Budd Doble, whose catarrhal name

so fills the nasal trump of fame . . .

Showing their keen sense of what the masses liked to look at—and more specifically what kinds of images they would pay between twenty-five cents and four dollars to own in lithograph form—Nathaniel Currier and his partner James Ives (their motto: “colored engravings for the people”) turned out nearly seven hundred prints (10 percent of Currier & Ives’s total output) with a harness-racing theme, simultaneously reflecting and fueling the Standardbred craze.

As time went on, and the breed started sorting itself out, a natural hierarchy developed: the swifter specimens tended to find their way to the racetrack while their more common relations pulled the nation’s passenger vehicles, trucks, fire wagons, and ambulances. Thus on a visit to the Grand Circuit or state fair, people often saw the latest, fastest models of what they had in their home stables—and they tended to form rooting interests based on horses who might be related by blood, albeit distantly, to their own. It was, in other words, a lot like NASCAR, though the enthusiasts were much better dressed.

Even in an age rife with record-smashing champions (Star Pointer, Lou Dillon, Anaconda) and a fawning press to burnish their images, Dan Patch was without dispute the flesh-and-blood beau ideal of his beloved breed. Just look at him! Yes, he had his physical abnormalities back toward the rear, so extreme in fact that anyone might wonder how he ever became a racehorse—but his head was as pretty as any Thoroughbred’s. His adventures on the racetrack were the stuff of which Victorian-era children’s books were made, and he was fast enough to get the public excited about the trickle-down effect he might have on the breed, and hence American life, once he retired to stud duty. (As a stallion, Dan Patch himself figured to be prohibitively expensive for most people, but middle-class folks might, for $50 or $100, breed to one of his offspring—and get, with luck, a horse who could help them cut ten or fifteen minutes off their daily commute.) What’s more, Dan Patch had exquisite timing, appearing at the precise midpoint of the Standardbred boom, just after the two-minute mile was broken (by the sorry-looking, patched-together pacer Star Pointer) and, more important, just before the automobile reached its tipping point and rendered the whole science of buggy-pulling forever moot. What he was doing on the racetrack—extending the limits of equine achievement—seemed genuinely important, not just mere sport. His fame spread to the castles of Europe, and American children (like Harry Truman) wrote him 50,000 fan letters a year. In Dan’s heyday, it almost seemed as if his P. T. Barnum–ish owner was being a bit modest when he proclaimed his pacer, in posters, handbills and newspaper ads, to be “The Most Wonderful Horse in the World!”

Because there is no one alive who saw Dan Patch race, and because there is scant film footage of him in action, I realize the modern reader, even one who has spent a lifetime devoted to sports, is likely to ask herself, Really? The most wonderful horse in the world, you say? I thought that was Seabiscuit—Hollywood assured me it was so. How come I’ve never even heard of Dan Patch? If there are no firsthand memories, because of the passage of time, where at least are the secondhand ones? Where is the monument to this beloved crazy-good athlete? Ruth has Yankee Stadium, and a plot in Hawthorne, New York, where people still shed a tear and leave a beer bottle. Man o’ War, the still-remembered Thoroughbred champion of the 1920s, is buried beneath a larger-than-life bronze of himself, in the Kentucky Horse Park. When Messenger, the great foundation sire of both the running and trotting horse breeds, died in 1808 in the Long Island hamlet of Buckram (now Locust Valley), “news of the death of the old patriarch spread with great rapidity,” wrote John H. Wallace, a distinguished historian of the American horse. “Soon the whole countryside was gathered to see the last of the king of horses and to assist at his burial. His grave was prepared at the foot of a chestnut tree and there he was deposited in his holiday clothing. In response to a consciousness that a hero was there laid away forever, a military organization was extemporized and volley after volley was fired over his grave.” America loves to memorialize its hero animals. Balto, the brave sled dog who carried desperately needed diphtheria serum between Nome and Anchorage in 1925, has an annual race—the Iditarod—in his honor, and a statue in Central Park, buffed to a high sheen by the tuchuses of tens of thousands of New York tykes. Where is the simple headstone—or the bronze statue or the towering shaft of granite—that marks the grave of the great Dan Patch?

A good question. So is this:

“Why is it that Dan Patch, the greatest horse, to my way of thinking, that harness racing has ever produced, should be forgotten to such an extent that one scarcely ever sees his name mentioned nowadays in the turf papers?” So goes a query posed by a reader of the Horse Review—in 1923. It is not easy today to find someone who has heard of the horse who was once a household name, who at least twice drew crowds of more than 100,000 just to watch him race against the clock—and who earned roughly $1 million a year at a time when the highest-paid baseball player, Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers, was making $12,000.

During the time I worked on this book I ran the name of Dan Patch by a random sampling of friends, acquaintances, work colleagues, relatives, cabdrivers, and yoga teachers. Outside of Oxford, Indiana, where the horse was born, and Savage, Minnesota, where he spent most of his life, very few knew who Dan was. People in New York City, where I live, were particularly clueless. A couple of them instantly came back at me with a line from “You’ve Got Trouble (Right Here in River City),” a song from Meredith Willson’s The Music Man (“Like to see some stuck-up jockey boy sitting on Dan Patch? Make your blood boil, I should say.”). But they admitted that they had no idea what the words meant; they might as well have been reciting the lyrics of “Louie, Louie.” Of the handful of other New Yorkers who said they recognized the name, one person identified Dan as a pre-Ruthian baseball player, and another had him confused with the two-legged nineteenth-century bridge-jumping daredevil Sam Patch. Still another said, “Isn’t Dan Patch a name for the devil?”—but he must have been thinking of Old Scratch, a fairly common synonym for Satan that occurs, for example, in Stephen Vincent Benet’s short story “The Devil and Daniel Webster.”

Alone among my Manhattan respondents, Bob Wallace, an old friend who has been the managing editor of Rolling Stone and is now an executive at ESPN, knew exactly who the horse was, and how deeply he had infiltrated the culture. “Oh, sure, the old harness-racing horse,” he said. Bob, who grew up in Arizona in the 1950s and ’60s, told me a story about watching dancers do the Pony (a minor offshoot of the Twist that involved a kind of prancing step; Chubby Checker had the hit single) on the weekly rock-and-roll show Hullabaloo when he was about ten. His parents, passing through the room at the time, pointed at the TV and laughed. “Why, that’s just the ol’ ‘Dan Patch Two-Step,’” his father had said, citing a hit song of the early 1900s, the sheet music for which occasionally crops up on eBay. Shortly before he related this tale, Bob, it turned out, had also watched—and hated—The Great Dan Patch, a black-and-white B movie that is as bad in its own twisted way as Fred Sasse’s 1957 book. (You can buy the DVD on eBay most days for a buck. The book, which surfaces infrequently, usually goes for about $20.)

After a while it dawned on me that Bob was the only person I’d encountered who knew of the horse but felt neutral about him. Virtually everyone else I polled was either ignorant of Dan or passionately devoted to collecting Patchiana. Dan Patch lunch boxes, pedal cars, Irish mails (four-wheeled toy scooters powered by a hand lever), flour sacks, tobacco tins—that and all of the bric-a-brac mentioned previously and more: the members of the Dan Patch cult sucked it off eBay or out of auction houses and added it, as often as not, to their household shrines. “My living room,” more than one has told me, “looks like a museum.” (This declaration is usually made in the presence of a spouse or other life partner who personifies the term long-suffering, and who stands a bit to the side and behind the collector, smiling wanly and rolling his or her eyes.) Dan Patch aficionados operate not in the just-tell-me-what-it’s-worth spirit of Antiques Roadshow but more like devout Irishwomen determinedly making a case—relic by relic, discarded crutch by discarded crutch—for the canonization of a beloved parish priest. They don’t just accumulate, they advocate. And in this way, I realized, Dan Patch is set apart from every other champion who trod the turf. For you can say what you want about Man o’ War, Seabiscuit, Citation, Native Dancer, Secretariat, Funny Cide, Smarty Jones, or even Barbaro—as gallantly as they ran, as regal as some looked draped in Kentucky Derby roses, no one would give you $50 today for a hunk of their mummified manure. Dan Patch is another matter entirely.

The physical evidence of Dan’s life is scattered throughout North America in the homes of—at most—three hundred serious collectors. I have met a man who showed me a mock-bamboo walking stick worn smooth at the handle by the hand of the obscure Hoosier farmer who was Dan Patch’s first trainer, and another man who owns an authentic left rear shoe (the Holy Grail of Dan Patch footwear), and a married couple who owns the barn where the horse lived from 1896, the year of his birth, until 1902. George Augustinack, the retired Burnsville, Minnesota, printer who owns the tail that may be Dan Patch’s, also has the horse’s harness, a not-so-miniature scale model of the farm where Dan lived from 1902 until 1916, and photographs of virtually everyone who worked there and their significant others; he has even, for some reason, acquired, when possible, the clothing those people were wearing in those photographs. “Sometime over the last forty years,” George notes unnecessarily, “I got carried away.” George has moldering currycombs that may contain Dan Patch hair and dander and boxes of canceled checks from the horse’s third and final owner, a Minneapolis entrepreneur named M. W. Savage—and George wants more. He wants, for example, M. W. Savage’s belt buckle and false teeth. “And I think I can get them, too,” he says, with a mysterious wink. As for Dan Patch dung, there is, unfortunately, none known to exist, but more than one of the faithful has shared with me his fantasy of owning some, and I’ve been assured by insiders that, at a well-advertised auction, a single turd with the proper provenance would go—quickly—for $800 to $1,000.

So, to pick up on a thread left dangling many paragraphs back, where is the headstone that says “The Most Wonderful Horse in the World”?

I think I know where Dan Patch is buried, approximately.

On a perfect late-summer afternoon in Scott County, Minnesota, I walked, escorted by an entourage of butterflies, past several No Trespassing signs and over railroad tracks and found a spot down by a creek, a particular bend in the stream that certain people had described to me. To check my location, I took from my pack an eight-by-ten aerial photograph of the area that I had been given by a great-grandson of a man who helped bury the horse on a steamy July day in 1916. That photo, on which a large, orange X had been drawn, had been passed along with considerable trepidation. “I hope no one is going to disturb the grave after all these years,” my source, who wishes to remain anonymous, had written in an accompanying note. His concern was understandable, if only because, in the late 1980s, a Savage man who told Jens Bohn the exact location of the horse’s remains had died suddenly a few days later. Since then, some people in Savage have theorized about a Dan Patch curse.

It struck me, as I stood there in three-foot-high grass, that I was not sure what I was doing. Why did it feel so necessary to seek out this place? The setting, to be sure, was paradisaical, and it’s always fun to trespass, especially in middle age, but what did I expect to find? I knew that the horse’s grave was unmarked, and an unmarked grave that is not set between two marked ones looks, ninety years later, like . . . nothing at all, really. So what was there to see? Even if I were a grave robber looking for bones to peddle to the Dan Patch cult, it seemed impossible that anything would be left in the muddy earth along this winding stream. For, you see, the great horse had been hurriedly stuck in a shallow, wet hole—I looked again at the photograph, then over toward an old cottonwood tree, then down at my boots; yes, this could be the spot—without even a simple pine box.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (June 2, 2009)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743291781

Raves and Reviews

"It's a terrific look at a legendary if now forgotten equine superstar named Dan Patch. Leerhsen does for early 20th-century American harness racing what Laura Hillenbrand's Seabiscuit did for Depression-era Thoroughbred racing." -- USA Today

"One of the many satisfactions of Crazy Good is that it goes farther than Seabiscuit -- Laura Hillenbrand's popular resurrection of another unlikely superstar -- in explaining how a horse could be so feted, then forgotten...With wit and a winking charm, Leerhsen, an executive editor at Sports Illustrated, makes sure this handsome brown stallion resonates...From start to finish, this book has legs." -- Newsweek

"Mr. Leerhsen's thoroughly entertaining history betrays no trace of the sentimentality that so often adheres to tales of bygone sports heroes...[Crazy Good] has the moments of sweetness and triumph that only a sports story can provide. Not least among the triumphs is the fact that, with Mr. Leerhsen's help, Dan Patch at long last has been given his due." -- Wall Street Journal

"Leerhsen vividly recounts Dan-mania and digs up dirt on the colorful gamblers and shady horse handlers of the 1900s. In rescuing Dan from the mists of history, he also draws a wry, moving account of America's first epidemic of sports fever." -- Entertainment Weekly

Resources and Downloads

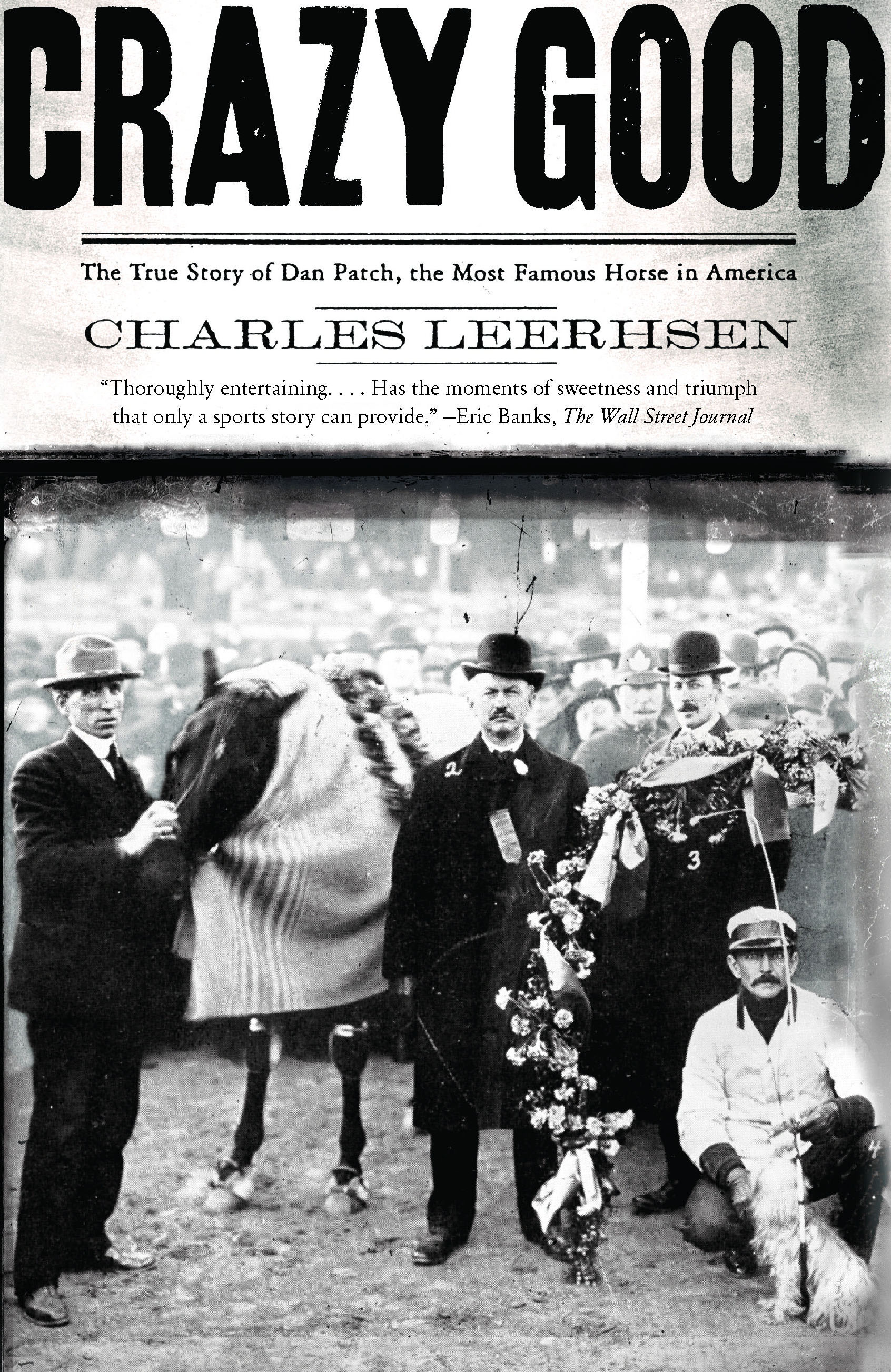

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Crazy Good Trade Paperback 9780743291781(1.0 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Charles Leerhsen Photograph by Steve Hoffman(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit