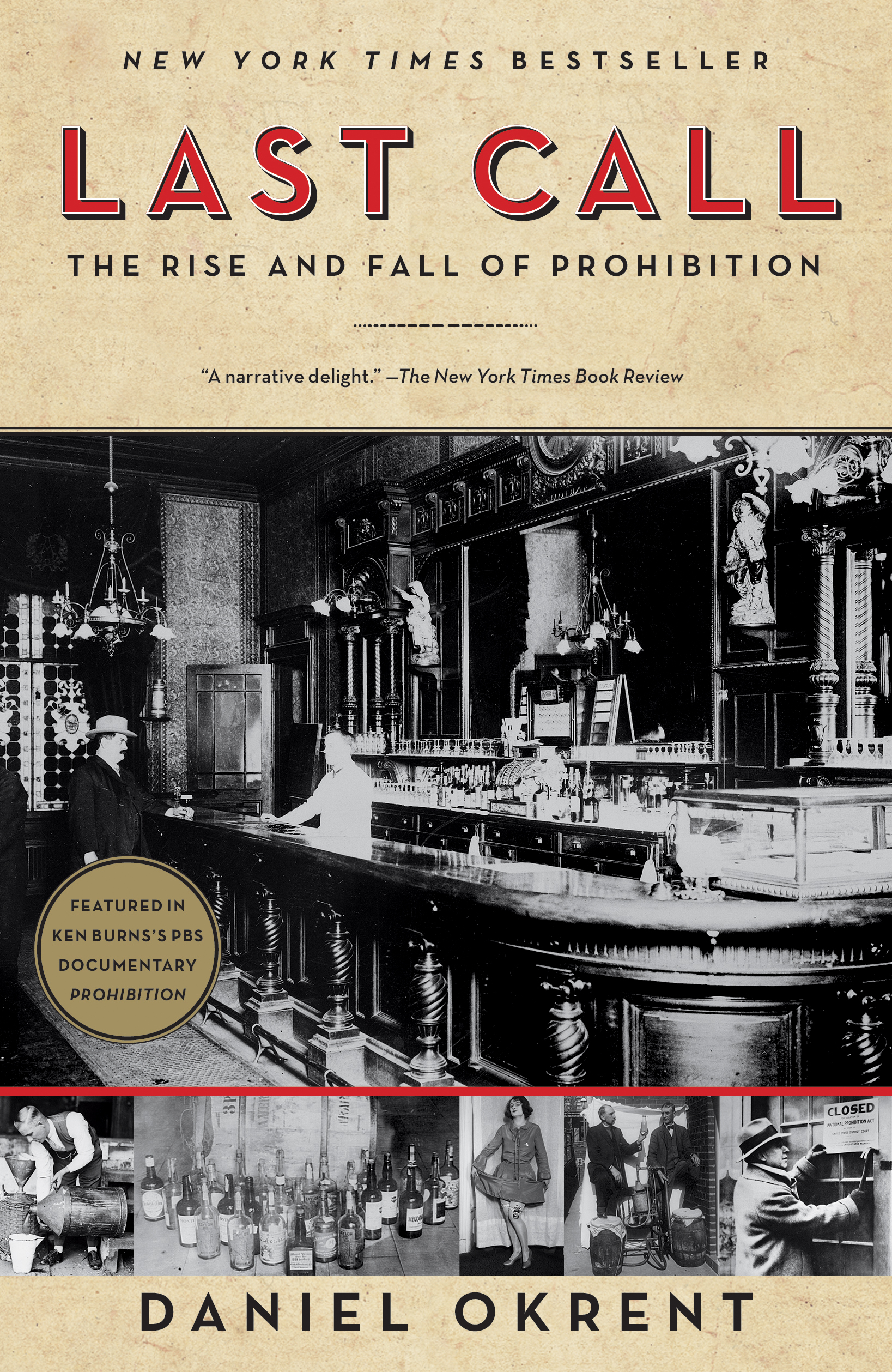

Last Call

The Rise and Fall of Prohibition

By Daniel Okrent

LIST PRICE $22.00

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

A brilliant, authoritative, and fascinating history of America’s most puzzling era, the years 1920 to 1933, when the US Constitution was amended to restrict one of America’s favorite pastimes: drinking alcoholic beverages.

From its start, America has been awash in drink. The sailing vessel that brought John Winthrop to the shores of the New World in 1630 carried more beer than water. By the 1820s, liquor flowed so plentifully it was cheaper than tea. That Americans would ever agree to relinquish their booze was as improbable as it was astonishing.

Yet we did, and Last Call is Daniel Okrent’s dazzling explanation of why we did it, what life under Prohibition was like, and how such an unprecedented degree of government interference in the private lives of Americans changed the country forever.

Writing with both wit and historical acuity, Okrent reveals how Prohibition marked a confluence of diverse forces: the growing political power of the women’s suffrage movement, which allied itself with the antiliquor campaign; the fear of small-town, native-stock Protestants that they were losing control of their country to the immigrants of the large cities; the anti-German sentiment stoked by World War I; and a variety of other unlikely factors, ranging from the rise of the automobile to the advent of the income tax.

Through it all, Americans kept drinking, going to remarkably creative lengths to smuggle, sell, conceal, and convivially (and sometimes fatally) imbibe their favorite intoxicants. Last Call is peopled with vivid characters of an astonishing variety: Susan B. Anthony and Billy Sunday, William Jennings Bryan and bootlegger Sam Bronfman, Pierre S. du Pont and H. L. Mencken, Meyer Lansky and the incredible—if long-forgotten—federal official Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who throughout the twenties was the most powerful woman in the country. (Perhaps most surprising of all is Okrent’s account of Joseph P. Kennedy’s legendary, and long-misunderstood, role in the liquor business.)

It’s a book rich with stories from nearly all parts of the country. Okrent’s narrative runs through smoky Manhattan speakeasies, where relations between the sexes were changed forever; California vineyards busily producing “sacramental” wine; New England fishing communities that gave up fishing for the more lucrative rum-running business; and in Washington, the halls of Congress itself, where politicians who had voted for Prohibition drank openly and without apology.

Last Call is capacious, meticulous, and thrillingly told. It stands as the most complete history of Prohibition ever written and confirms Daniel Okrent’s rank as a major American writer.

From its start, America has been awash in drink. The sailing vessel that brought John Winthrop to the shores of the New World in 1630 carried more beer than water. By the 1820s, liquor flowed so plentifully it was cheaper than tea. That Americans would ever agree to relinquish their booze was as improbable as it was astonishing.

Yet we did, and Last Call is Daniel Okrent’s dazzling explanation of why we did it, what life under Prohibition was like, and how such an unprecedented degree of government interference in the private lives of Americans changed the country forever.

Writing with both wit and historical acuity, Okrent reveals how Prohibition marked a confluence of diverse forces: the growing political power of the women’s suffrage movement, which allied itself with the antiliquor campaign; the fear of small-town, native-stock Protestants that they were losing control of their country to the immigrants of the large cities; the anti-German sentiment stoked by World War I; and a variety of other unlikely factors, ranging from the rise of the automobile to the advent of the income tax.

Through it all, Americans kept drinking, going to remarkably creative lengths to smuggle, sell, conceal, and convivially (and sometimes fatally) imbibe their favorite intoxicants. Last Call is peopled with vivid characters of an astonishing variety: Susan B. Anthony and Billy Sunday, William Jennings Bryan and bootlegger Sam Bronfman, Pierre S. du Pont and H. L. Mencken, Meyer Lansky and the incredible—if long-forgotten—federal official Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who throughout the twenties was the most powerful woman in the country. (Perhaps most surprising of all is Okrent’s account of Joseph P. Kennedy’s legendary, and long-misunderstood, role in the liquor business.)

It’s a book rich with stories from nearly all parts of the country. Okrent’s narrative runs through smoky Manhattan speakeasies, where relations between the sexes were changed forever; California vineyards busily producing “sacramental” wine; New England fishing communities that gave up fishing for the more lucrative rum-running business; and in Washington, the halls of Congress itself, where politicians who had voted for Prohibition drank openly and without apology.

Last Call is capacious, meticulous, and thrillingly told. It stands as the most complete history of Prohibition ever written and confirms Daniel Okrent’s rank as a major American writer.

Excerpt

Last Call

Prologue

January 16, 1920

THE STREETS OF San Francisco were jammed. A frenzy of cars, trucks, wagons, and every other imaginable form of conveyance crisscrossed the town and battled its steepest hills. Porches, staircase landings, and sidewalks were piled high with boxes and crates delivered on the last possible day before transporting their contents would become illegal. The next morning, the Chronicle reported that people whose beer, liquor, and wine had not arrived by midnight were left to stand in their doorways “with haggard faces and glittering eyes.” Just two weeks earlier, on the last New Year’s Eve before Prohibition, frantic celebrations had convulsed the city’s hotels and private clubs, its neighborhood taverns and wharfside saloons. It was a spasm of desperate joy fueled, said the Chronicle, by great quantities of “bottled sunshine” liberated from “cellars, club lockers, bank vaults, safety deposit boxes and other hiding places.” Now, on January 16, the sunshine was surrendering to darkness.

San Franciscans could hardly have been surprised. Like the rest of the nation, they’d had a year’s warning that the moment the calendar flipped to January 17, Americans would only be able to own whatever alcoholic beverages had been in their homes the day before. In fact, Americans had had several decades’ warning, decades during which a popular movement like none the nation had ever seen—a mighty alliance of moralists and progressives, suffragists and xenophobes—had legally seized the Constitution, bending it to a new purpose.

Up in the Napa Valley to the north of San Francisco, where grape growers had been ripping out their vines and planting fruit trees, an editor wrote, “What was a few years ago deemed the impossible has happened.” To the south, Ken Lilly—president of the Stanford University student body, star of its baseball team, candidate for the U.S. Olympic track team—was driving with two classmates through the late-night streets of San Jose when his car crashed into a telephone pole. Lilly and one of his buddies were badly hurt, but they would recover. The forty-gallon barrel of wine they’d been transporting would not. Its disgorged contents turned the street red.

Across the country on that last day before the taps ran dry, Gold’s Liquor Store placed wicker baskets filled with its remaining inventory on a New York City sidewalk; a sign read “Every bottle, $1.” Down the street, Bat Masterson, a sixty-six-year-old relic of the Wild West now playing out the string as a sportswriter in New York, observed the first night of constitutional Prohibition sitting alone in his favorite bar, glumly contemplating a cup of tea. Under the headline GOODBYE, OLD PAL!, the American Chicle Company ran newspaper ads featuring an illustration of a martini glass and suggesting the consolation of a Chiclet, with its “exhilarating flavor that tingles the taste.”

In Detroit that same night, federal officers shut down two illegal stills (an act that would become common in the years ahead) and reported that their operators had offered bribes (which would become even more common). In northern Maine, a paper in New Brunswick reported, “Canadian liquor in quantities from one gallon to a truckload is being hidden in the northern woods and distributed by automobile, sled and iceboat, on snowshoes and on skis.” At the Metropolitan Club in Washington, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt spent the evening drinking champagne with other members of the Harvard class of 1904.

There were of course those who welcomed the day. The crusaders who had struggled for decades to place Prohibition in the Constitution celebrated with rallies and prayer sessions and ritual interments of effigies representing John Barleycorn, the symbolic proxy for alcohol’s evils. No one marked the day as fervently as evangelist Billy Sunday, who conducted a revival meeting in Norfolk, Virginia. Ten thousand grateful people jammed Sunday’s enormous tabernacle to hear him announce the death of liquor and reveal the advent of an earthly paradise. “The reign of tears is over,” Sunday proclaimed. “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and the children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent.”

A similarly grandiose note was sounded by the Anti-Saloon League, the mightiest pressure group in the nation’s history. No other organization had ever changed the Constitution through a sustained political campaign; now, on the day of its final triumph, the ASL declared that “at one minute past midnight . . . a new nation will be born.” In a way, editorialists at the militantly anti-Prohibition New York World perceived the advent of a new nation, too. “After 12 o’clock tonight,” the World said, “the Government of the United States as established by the Constitution and maintained for nearly 131 years will cease to exist.” Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane may have provided the most accurate view of the United States of America on the edge of this new epoch. “The whole world is skew-jee, awry, distorted and altogether perverse,” Lane wrote in his diary on January 19. “. . . Einstein has declared the law of gravitation outgrown and decadent. Drink, consoling friend of a Perturbed World, is shut off; and all goes merry as a dance in hell!”

? ? ?

How did it happen? How did a freedom-loving people decide to give up a private right that had been freely exercised by millions upon millions since the first European colonists arrived in the New World? How did they condemn to extinction what was, at the very moment of its death, the fifth-largest industry in the nation? How did they append to their most sacred document 112 words that knew only one precedent in American history? With that single previous exception, the original Constitution and its first seventeen amendments limited the activities of government, not of citizens. Now there were two exceptions: you couldn’t own slaves, and you couldn’t buy alcohol.

Few realized that Prohibition’s birth and development were much more complicated than that. In truth, January 16, 1920, signified a series of innovations and alterations revolutionary in their impact. The alcoholic miasma enveloping much of the nation in the nineteenth century had inspired a movement of men and women who created a template for political activism that was still being followed a century later. To accomplish their ends they had also abetted the creation of a radical new system of federal taxation, lashed their domestic goals to the conduct of a foreign war, and carried universal suffrage to the brink of passage. In the years ahead, their accomplishments would take the nation through a sequence of curves and switchbacks that would force the rewriting of the fundamental contract between citizen and government, accelerate a recalibration of the social relationship between men and women, and initiate a historic realignment of political parties.

In 1920 could anyone have believed that the Eighteenth Amendment, ostensibly addressing the single subject of intoxicating beverages, would set off an avalanche of change in areas as diverse as international trade, speedboat design, tourism practices, soft-drink marketing, and the English language itself? Or that it would provoke the establishment of the first nationwide criminal syndicate, the idea of home dinner parties, the deep engagement of women in political issues other than suffrage, and the creation of Las Vegas? As interpreted by the Supreme Court and as understood by Congress, Prohibition would also lead indirectly to the eventual guarantee of the American woman’s right to abortion and simultaneously dash that same woman’s hope for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.

Prohibition changed the way we live, and it fundamentally redefined the role of the federal government. How the hell did it happen?

Prologue

January 16, 1920

THE STREETS OF San Francisco were jammed. A frenzy of cars, trucks, wagons, and every other imaginable form of conveyance crisscrossed the town and battled its steepest hills. Porches, staircase landings, and sidewalks were piled high with boxes and crates delivered on the last possible day before transporting their contents would become illegal. The next morning, the Chronicle reported that people whose beer, liquor, and wine had not arrived by midnight were left to stand in their doorways “with haggard faces and glittering eyes.” Just two weeks earlier, on the last New Year’s Eve before Prohibition, frantic celebrations had convulsed the city’s hotels and private clubs, its neighborhood taverns and wharfside saloons. It was a spasm of desperate joy fueled, said the Chronicle, by great quantities of “bottled sunshine” liberated from “cellars, club lockers, bank vaults, safety deposit boxes and other hiding places.” Now, on January 16, the sunshine was surrendering to darkness.

San Franciscans could hardly have been surprised. Like the rest of the nation, they’d had a year’s warning that the moment the calendar flipped to January 17, Americans would only be able to own whatever alcoholic beverages had been in their homes the day before. In fact, Americans had had several decades’ warning, decades during which a popular movement like none the nation had ever seen—a mighty alliance of moralists and progressives, suffragists and xenophobes—had legally seized the Constitution, bending it to a new purpose.

Up in the Napa Valley to the north of San Francisco, where grape growers had been ripping out their vines and planting fruit trees, an editor wrote, “What was a few years ago deemed the impossible has happened.” To the south, Ken Lilly—president of the Stanford University student body, star of its baseball team, candidate for the U.S. Olympic track team—was driving with two classmates through the late-night streets of San Jose when his car crashed into a telephone pole. Lilly and one of his buddies were badly hurt, but they would recover. The forty-gallon barrel of wine they’d been transporting would not. Its disgorged contents turned the street red.

Across the country on that last day before the taps ran dry, Gold’s Liquor Store placed wicker baskets filled with its remaining inventory on a New York City sidewalk; a sign read “Every bottle, $1.” Down the street, Bat Masterson, a sixty-six-year-old relic of the Wild West now playing out the string as a sportswriter in New York, observed the first night of constitutional Prohibition sitting alone in his favorite bar, glumly contemplating a cup of tea. Under the headline GOODBYE, OLD PAL!, the American Chicle Company ran newspaper ads featuring an illustration of a martini glass and suggesting the consolation of a Chiclet, with its “exhilarating flavor that tingles the taste.”

In Detroit that same night, federal officers shut down two illegal stills (an act that would become common in the years ahead) and reported that their operators had offered bribes (which would become even more common). In northern Maine, a paper in New Brunswick reported, “Canadian liquor in quantities from one gallon to a truckload is being hidden in the northern woods and distributed by automobile, sled and iceboat, on snowshoes and on skis.” At the Metropolitan Club in Washington, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt spent the evening drinking champagne with other members of the Harvard class of 1904.

There were of course those who welcomed the day. The crusaders who had struggled for decades to place Prohibition in the Constitution celebrated with rallies and prayer sessions and ritual interments of effigies representing John Barleycorn, the symbolic proxy for alcohol’s evils. No one marked the day as fervently as evangelist Billy Sunday, who conducted a revival meeting in Norfolk, Virginia. Ten thousand grateful people jammed Sunday’s enormous tabernacle to hear him announce the death of liquor and reveal the advent of an earthly paradise. “The reign of tears is over,” Sunday proclaimed. “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and the children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent.”

A similarly grandiose note was sounded by the Anti-Saloon League, the mightiest pressure group in the nation’s history. No other organization had ever changed the Constitution through a sustained political campaign; now, on the day of its final triumph, the ASL declared that “at one minute past midnight . . . a new nation will be born.” In a way, editorialists at the militantly anti-Prohibition New York World perceived the advent of a new nation, too. “After 12 o’clock tonight,” the World said, “the Government of the United States as established by the Constitution and maintained for nearly 131 years will cease to exist.” Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane may have provided the most accurate view of the United States of America on the edge of this new epoch. “The whole world is skew-jee, awry, distorted and altogether perverse,” Lane wrote in his diary on January 19. “. . . Einstein has declared the law of gravitation outgrown and decadent. Drink, consoling friend of a Perturbed World, is shut off; and all goes merry as a dance in hell!”

? ? ?

How did it happen? How did a freedom-loving people decide to give up a private right that had been freely exercised by millions upon millions since the first European colonists arrived in the New World? How did they condemn to extinction what was, at the very moment of its death, the fifth-largest industry in the nation? How did they append to their most sacred document 112 words that knew only one precedent in American history? With that single previous exception, the original Constitution and its first seventeen amendments limited the activities of government, not of citizens. Now there were two exceptions: you couldn’t own slaves, and you couldn’t buy alcohol.

Few realized that Prohibition’s birth and development were much more complicated than that. In truth, January 16, 1920, signified a series of innovations and alterations revolutionary in their impact. The alcoholic miasma enveloping much of the nation in the nineteenth century had inspired a movement of men and women who created a template for political activism that was still being followed a century later. To accomplish their ends they had also abetted the creation of a radical new system of federal taxation, lashed their domestic goals to the conduct of a foreign war, and carried universal suffrage to the brink of passage. In the years ahead, their accomplishments would take the nation through a sequence of curves and switchbacks that would force the rewriting of the fundamental contract between citizen and government, accelerate a recalibration of the social relationship between men and women, and initiate a historic realignment of political parties.

In 1920 could anyone have believed that the Eighteenth Amendment, ostensibly addressing the single subject of intoxicating beverages, would set off an avalanche of change in areas as diverse as international trade, speedboat design, tourism practices, soft-drink marketing, and the English language itself? Or that it would provoke the establishment of the first nationwide criminal syndicate, the idea of home dinner parties, the deep engagement of women in political issues other than suffrage, and the creation of Las Vegas? As interpreted by the Supreme Court and as understood by Congress, Prohibition would also lead indirectly to the eventual guarantee of the American woman’s right to abortion and simultaneously dash that same woman’s hope for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.

Prohibition changed the way we live, and it fundamentally redefined the role of the federal government. How the hell did it happen?

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (May 31, 2011)

- Length: 480 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743277044

Awards and Honors

- ALA Notable Book

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Last Call Trade Paperback 9780743277044(3.1 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Daniel Okrent Photograph © Raymond Elman(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit