Table of Contents

About The Book

What's a palooza?

An activity that keeps kids from uttering those terrifying words, "I'm bored!"

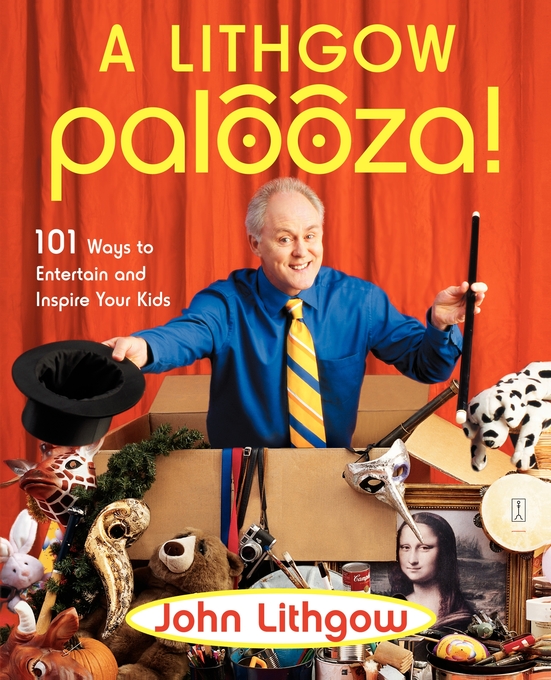

You may know John Lithgow as star of stage, screen, and television or even as a bestselling children's book author. But his most important role -- parent -- was also the most fun. Whether building cardboard castles or putting on a King and I puppet show or conducting a treasure hunt in the National Gallery of Art, John has spent years perfecting the art of the palooza.

A palooza is easy to do!

A palooza doesn't cost much (some cost absolutely nothing)

A palooza is instigated or organized by parents but is quickly taken over by children

A palooza may involve a computer but never the TV

A palooza may use all varieties of arts and crafts

A palooza may secretly teach children (and parents!) a thing or two

A palooza is entertaining for the entire family

A palooza depends entirely on the inexhaustible creativity, ingenuity, imagination, and sense of fun of young minds

This book contains 101 ideas for creating paloozas for children ages 3 to 12 wherever you are. Grouped according to interests and themes -- like art, drama, music, vacations, and birthdays -- and incorporating lots of extrapaloozas, fun facts for parent and child, and suggested additional reading for all ages, John's paloozas range from adopting your own soup can for a day to inventing your own secret language to establishing left-handed day or creating a self-portrait. A Lithgow Palooza! is an utterly unique collection of original activities guaranteed to transform any household from bored to bubbling with fun.

An activity that keeps kids from uttering those terrifying words, "I'm bored!"

You may know John Lithgow as star of stage, screen, and television or even as a bestselling children's book author. But his most important role -- parent -- was also the most fun. Whether building cardboard castles or putting on a King and I puppet show or conducting a treasure hunt in the National Gallery of Art, John has spent years perfecting the art of the palooza.

A palooza is easy to do!

A palooza doesn't cost much (some cost absolutely nothing)

A palooza is instigated or organized by parents but is quickly taken over by children

A palooza may involve a computer but never the TV

A palooza may use all varieties of arts and crafts

A palooza may secretly teach children (and parents!) a thing or two

A palooza is entertaining for the entire family

A palooza depends entirely on the inexhaustible creativity, ingenuity, imagination, and sense of fun of young minds

This book contains 101 ideas for creating paloozas for children ages 3 to 12 wherever you are. Grouped according to interests and themes -- like art, drama, music, vacations, and birthdays -- and incorporating lots of extrapaloozas, fun facts for parent and child, and suggested additional reading for all ages, John's paloozas range from adopting your own soup can for a day to inventing your own secret language to establishing left-handed day or creating a self-portrait. A Lithgow Palooza! is an utterly unique collection of original activities guaranteed to transform any household from bored to bubbling with fun.

Excerpt

CHAPTER ONE: the big paloozas

Adopt-a-Soup Can

Hold on to your hats, this is a nutty palooza. But trust me, the kids will love it. Andy Warhol exalted sameness in his Campbell's Soup Can series. This palooza brings an individual can of soup to life and gives it a personality all its own.

What's the Palooza?

Choose a can of soup to adopt. Roam the soup aisle at the grocery store and read aloud the names of various kinds of soup. Pick a soup that tickles your fancy and bring it home to "live." Invent a name that suits your soup can's personality; think Beany Bacon, Alpha Beth Soup, Tommy Tomato, Charlie Chowder, and so on.

At home with the soup, make a birth certificate for it. Look at your own birth certificate as a sidelight. Include the soup can's name, date, time, and place of birth (date of purchase, and store name), and the name of its legal guardian (your name). Once the soup can is named and has proper documentation, invent the soup can's life story and personality traits. Then dress it accordingly.

To dress the soup can, carefully remove the paper label. Trace the outline of the label onto a piece of paper to make a can-sized "dress" pattern. Design and color the new dress (or pants, bathing suit, tutu, and so on) for the can using the pattern. Thinking of its personality, use the soup can's favorite colors and patterns. Stripes. Solids. Citrussy oranges and pinks. Businessy blues and grays. Don't forget to leave space to draw a face onto the paper. Outfit the can by taping on his new clothes. Add hair by attaching pieces of yarn to the top of the can with tape.

A soup can's accessories say much about his personality. Dress him up for a business meeting by adding a little necktie. Draw an umbrella and handbag for her. Or a baseball cap and glove for him.

What's your soup can like? She's a little bit shy, but loves Audrey Hepburn movies. He's always green with pea-soup envy. Does she socialize with other soups or prefer the company of mixed nuts? The idea is to make the can as interesting a character as possible. And to get her involved in your life! She comes to the table for meals. She helps with homework. She goes to ballet class and soccer practice. She may even go to school for show-and-tell. Be sure to tell how she got that dent below her ingredients list. It's quite a story.

Extrapalooza

Souper Can!

Souper Can is a soup-can superhero. He's got whatever powers you dream up for him. (And he's probably wearing a cape and lots of spandex!) Take photos or draw pictures of Souper Can doing outrageous superhero kinds of things. Use the photos or drawings to make a comic book of Souper Can's adventures. Souper Can lands on the roof of the dollhouse for an amazing rescue of a cat stranded on the second-story windowsill. Souper Can bravely cleans his plate of Mom's asparagus casserole. Souper Can discusses playground safety with the school principal. Souper Can looks under a child's bed with concern. Write funny captions or dialogue to go with the pictures.

Junk Garden

By planting in unusual objects, planting an entire garden in an old tire, or decorating a whole garden with quirky found objects, kids get to flex their resourceful and imaginative muscles. They also gain an appreciation for whimsy in the garden and for the earthly delights of a garden itself.

What's the Palooza?

Create a junk garden by incorporating the odd and unusual in the backyard, family garden, or outdoor terrace by using household items -- from metal buckets or work boots to red wagons and old chairs -- as planters or garden decoration. One person's old frying pan is another's dream ornament for a patch of scarlet begonias. A toy truck displayed on a rock just so becomes an appealing garden sculpture.

Choose a patch of ground in your yard or garden that can be designated as the "junk garden." How big a patch of ground you choose depends on the size of your property, of course, and how much space you want to devote in the yard for the activity. A minimum of one square yard is plenty to start. Mark it off with stakes and twine, twigs, sticks, and stones, or other objects you gather for the garden border. Use seashells, wooden blocks, dominos, board game pieces, or even plastic race car tracks.

Once the border is defined, the junk garden is ready to be planted. Plant objects only or a combination of objects and plants. You may want to plant your objects first, so as to avoid trampling the plants. Or you may want to get impatiens or petunias in the ground first, so as to invent creative displays around them with found objects. You can also skip real plants altogether. Go wild "planting" colorful cups and saucers you've collected at yard sales or plastic juice cups. Dig a little hole in the ground and "plant" a cup so that it is sticking in the ground about halfway. Or paint wooden spoons bright colors and plant them as flowers in your garden. Plant action figures, plastic animals, Barbie, you name it.

Plant items from the kitchen or basement such as a yardstick, an old boot, measuring spoons, or flatware. Be artful about the planting and think of interesting ways to combine objects and plants. Use saucers as backdrops for small plants. Make a perch for birds out of an old spoon tied tightly to a twig with rubber bands. Tend the junk garden carefully and water frequently. Change or move the objects as you collect new items or simply to redesign the garden.

Extrapaloozas

Chair Trellis

Look for interesting old chairs at yard sales and antique stands. Choose a chair that has the patina of age or might be painted a favorite color. Position the chair in a spot that will accommodate the kind of plant you wish to grow, sun-, soil-, and water-wise. Ask your plant store for recommendations or choose a vine such as honeysuckle, sweet potato, passion flower, or a flowering bean vine, and train the vine to climb the chair. Voilà. Chair trellis.

Tire Garden

Use an old tire to make a raised bed. Fill the center of the tire with good soil and plant a tomato seedling in the center. Decorate the tire garden with Barbie shoes or marbles or other found objects. Then make tomato sandwiches in summer.

Junk Garden Themes

Choose a theme. Go all natural and use only twigs and stones, bird feathers, leaves, shells, moss-covered stones from a stream. Or make the garden dinosaurs-only. Create an imaginary universe in the garden using dollhouse furniture, "fairy furniture" made from items you collect (pipe cleaners, Popsicle sticks, toothpicks, old crayons), or twig tepees. Choose plants by theme, as well. Plant basil, lemon thyme, mint, dill, and lavender in a "nose garden." Plant snapdragon, tiger lily, catnip, and spider plants for a "zoo garden."

Container Planting

If it holds soil, and something will grow in it, it's a garden. Plant something wonderful in an old work boot. Or an old cast-iron frying pan. Or a little red wagon. Follow potting instructions for container planting from your favorite gardening book or rely on your own green thumb (paying attention to drainage, using good professional-grade potting soil, and so on), and plant to your hearts' content. Try lavender in the boot. Begonias in the wagon. Use yogurt cup liners (with a hole punched in the bottom for drainage) for planting in mugs you collect in thrift stores and yard sales. Have a mug garden collection.

Flowers for Your Garden

For immediate results in the flowerbed, plant seedlings or small plants from the nursery. Try annuals such as nasturtiums, petunias, impatiens, or verbena. Sunflowers are easy to plant from seed, and you can see growth almost daily. Green peas, lettuces, and pumpkins are fast-growing vegetables. Hollyhocks and daisies, two old-fashioned perennials, also mix well in a junk garden.

Bridges

I've never outgrown my sense of amazement at the sheer audacity of a bridge. The idea of spanning an enormous body of water while appearing suspended in air by a few thin steel threads is magical. No wonder children -- and most adults -- are endlessly fascinated by bridges.

What's the Palooza?

An exploration of bridges, mind-boggling and mysterious -- think about them, design them, build them!

Make up a quiz entirely of questions about bridges: What is the longest bridge in the world? The highest bridge? The strongest bridge? The oldest bridge? What country has the most bridges? What are all the types of bridges? What are the great bridges of the world?

Once the quiz is finished, take a trip to the library or the Internet. In looking for quiz answers, you can find out about famous bridges around the world, the history of bridges, how bridges are built, what materials they're made from, and so forth. You can also find out about the dozens of types of bridges, including suspension, cantilever beam, cable, truss, swing, and arch, to name a few. Try to find an example of each kind of bridge in your search.

Now that you know something about bridges, start building bridges out of as many different common materials as you can think of: paper, sticks, stones, clay, blocks, Legos, wire, magnets, candy, cards, toothpicks, you name it.

Begin by sketching a simple bridge. Then decide what material would work best for that particular bridge design. An arched bridge might be built out of plasticine. A truss bridge could be made of Popsicle sticks, white glue or Scotch tape, and string.

One of the simplest of all bridges is made of an 8 1/2 x 11 inch sheet of paper and six books. Take the piece of paper and rest opposite ends on a stack of three books each. Here's where the mystery of science comes in: If you try to put a weight on this paper bridge, say a few pennies, it will collapse. If you fold the paper a few times, it magically holds the weight of the pennies.

If you're feeling ambitious, make a simple scale-model truss bridge, using toothpicks, glue, cardboard, and a marker. Go to http://www.yesmag.bc.ca/proj ects/bridge.html and follow the step-by-steps.

A terrific book all about build-it-yourself bridges is Bridges! Amazing Structures to Design, Build & Test by Michael Kline, Carol Johmann, and Elizabeth Reith. It's a great introduction to the whole wide world of bridges, with history, science, and lots of hands-on designing, building, and testing activities.

And check out www.pontifex2.com, featuring Pontifex II software, which allows you to build and test a bridge of your own design. Then you can use the 3-D graphics feature to view your creation from any angle, including "first person," where you're in the driver's seat of the test car.

Extrapaloozas

Travel Bridge

Start a "collection" of bridges by keeping a special bridge notebook in the car. Then, whenever the family drives anywhere, pay attention to every bridge, no matter how small, you cross. Try to catch the name of the bridge and include the town or state it's in, what body of water it spans, or if it covers a landform of some kind, such as a ravine. See if you can figure out what type of bridge it is, too: suspension? arch? cantilevered? Maybe you give yourself extra points for crossing an unusual bridge -- a covered bridge, for example. But it's plenty of fun simply to keep a lifelong list of bridges.

A Game of Bridge

Play an old-school game of bridge -- London Bridge. Building bridges in the Middle Ages was fraught with suspicion because the bridge might disturb a place inhabited by devils and arouse their anger. In the original medieval game of London Bridge, being "caught" by the bridge was a way of separating players into devils and angels.

Two players stand face-to-face and clasp each other's hands high in front of them to form the bridge. Sing the words to the song as the other players walk or run under the bridge. To capture someone, the two bridge builders lower their arms whenever the verse reaches the words "My fair lady." Once every player has been caught, they divide in half, holding on to each other's waist to form a chain and play tug-of-war. (The tug-of-war symbolized the battle between good and evil -- devils and angels.)

Repartee

Bashful. Buttoned up. Taciturn. Tongue-tied. Wouldn't you rather be the one they called enlightening and effervescent, loquacious and mellifluous? It's all a matter of exercising your conversation muscles -- and having fun, of course. They don't call it "wordplay" for nothing!

What's the Palooza?

Practice the fine art of conversation. It's not always easy to think of something to say, especially to someone you've just met. But there are simple ways to get a conversation started, and great ways to make it interesting.

The best place to start to explore conversation opportunities is around the dinner table at home. Usually the adults drive the dialogue, and it's easy to just let them do that. But you're tired of the "How was school? Did you do your homework?" dinner conversation you usually have. So take matters into your own hands. Throw a few provocative conversation starters out there and see what happens.

Ask questions. Choose one person to ask one question. Others around the table may want to answer the question as well, or the question may lead to another topic of conversation. Here are some ideas for questions to ask, but you should definitely think up some of your own:

If you could live anywhere in the world, where would it be?

What famous person would you like to meet?

What is your earliest childhood memory?

What were your favorite cartoons when you were a kid?

If someone gave you $1,000 to spend in one day, how would you spend it?

If you could be invisible for a day, where would you go and what would you do?

How would you describe your perfect day?

Flash the facts. Share interesting pieces of information that are likely to spur conversation. For instance, did you know that no word in the English language rhymes with month, orange, silver, and purple? Or that the average person falls asleep in seven minutes? Or that an ostrich's eye is bigger than its brain? Collect tidbits like this from books and magazines that you read and use them to get people talking.

Use the news to stir things up. Did you see a story on the sports page calling your dad's favorite baseball player "trade bait"? Did you hear on the radio that the government says ketchup counts as a vegetable in your school lunch? Did you see a story about someone spotting a UFO? Share these kinds of "news" bites, and you're sure to spark lively debates about what's fact and what's opinion -- or what's fact and what's fiction!

Know what you think. When you hear a news story or listen to a conversation, don't just let it go in one ear and out the other. Stop and ask yourself, "What do I think about that?" Pay attention to subjects and issues being discussed around you and try to work out your opinion on them. It's okay to have mixed feelings about something (on the one hand, on the other...) because things are rarely crystal clear or black and white. Just try to know what you think and practice expressing it at the table. Who do you think would make a good president -- and why? Do you think there should be a designated hitter in major league baseball -- why or why not? Do you think that human cloning is possible -- and if so, should it be allowed? The more you know about what you think, the more there is to talk about!

Extrapaloozas

Hi-Point, Lo-Point

You can play Hi-Point, Lo-Point with family and friends or people you've just met. Start by sharing the hi-point, or best moment, of your day. Then describe the lo-point, or least pleasant part of your day. Hi-point? I got an A on my science test. Lo-point? My sandwich fell on the floor at lunch. Get everyone to share their hi-points and lo-points. Compare stories -- who had the highest hi-point and the lowest lo-point? Play hi-point, lo-point every night at dinner and soon you'll have a Hi-Point, Lo-Point Hall of Fame. And shouldn't the person with the lowest lo-point not have to do dishes?

Conversation Piece

A conversation piece is an object that is so unusual and provocative that people can't help talking about it. It doesn't matter whether it's shocking or beautiful or rare or bizarre, as long as it arouses interest. If you are in someone's home and you see a skull on a bookshelf, for instance, or an elegant orchid on a table, you can be sure these are meant to be conversation pieces. Sometimes people dress in an extreme or unusual manner in order to be a conversation piece. Or they'll wear a startling piece of jewelry or over-the-top hat. Conversation pieces command attention, to be sure, but they don't guarantee that sparkling conversation will happen. That's still up to you.

It's About Time

It's hard to imagine getting through a day without our alarm clocks, wristwatches, and wall clocks. But ancient societies experienced and measured time in completely different ways (and they did just fine, didn't they?). This palooza explores some aspects of time we rarely take the time to think about.

What's the Palooza?

pard

Devote a day to the exploration of time, and see what it would be like to live without our modern mechanical clocks at all. Before the late fifteenth century, mechanical clocks as we know them did not exist. But people came up with other ingenious ways to measure time. We've all heard of hourglasses and sundials. But there were also fire clocks, which were made of a burning candle with lines marking each hour, or even an incense stick that burned at a steady rate. Water clocks measured time by the flow of water through a small hole. In some of the most primitive cultures, time has been measured in vague but concrete approximations -- people would talk of "the time it takes to cook a pan of beans" as a unit of time. And, of course, without reliable tools for measuring time, the sun acted as the biggest indicator of time.

Make a sundial before the day you will spend thinking about time. You will need a large piece of heavy paper or cardboard, a short pencil, a small amount of clay, and a watch. Place the pencil point down in the center of the cardboard, using the clay to secure it firmly. On a clear, sunny day, put the cardboard outside soon after the sun rises, making sure to put it in a spot that will not be obscured by shadow during any part of the day. If necessary, the cardboard can be held in place with small stones or a brick. At every hour until sunset, mark the place on the cardboard where the end of the pencil's shadow lies and the current time. Be careful not to shift or disturb the cardboard, or your measurement will be inaccurate.

The next day (which should probably be a Saturday, Sunday, or other no-school day), rise with the sun -- or whenever your own biological clock tells you to -- and let the fun begin! Unplug, put away, or cover up all your clocks, and use your sundial instead.

Over the course of the day, see if anyone in the family really has a good sense of time. One at a time, have each person lie down on the floor and close his eyes and start the stopwatch. Whenever he thinks one minute, or two minutes, or five minutes have passed, he stops the stopwatch and checks the amount of time that really passed. Write down each person's name and how many minutes he actually spent lying on the ground. Whoever gets the closest to ten minutes wins the Natural Timekeeper Award.

Mostly what you'll discover is how out of touch everyone's sense of time really is. Try to brainstorm the various ways that you can measure the passing of the day without looking at a clock or watch.

Talk about units of time drawn from the details of your day-to-day life: how about the time it takes the answering machine to pick up? The time it takes to lock the front door? See if you can incorporate these time units into your everyday conversations, such as, "Dinner will be ready in the time it takes to walk around the block." And then walk around the block, because that's a good idea, anyway!

At the end of this day of primitive timekeeping, it might be hard for you to decide whether you are lucky or unlucky to live lives where time is precise to the second. Does it make your life more organized or more frenzied? Would it be possible to abandon our traditional perception and measure of time completely? Never look at a watch or even your sundial? Imagine time not as cyclical, rather as one long line into the future without any measure but the quality of how you spend it. Read a good book until your eyes get tired. Then take a lovely nap until you wake up. Eat when you are hungry. Take a bath when it would feel good. Shaking off some of our micro-measurements of time would at least be a relaxing vacation!

Extrapaloozas

Time Management Race

Set up relay teams, with one or more persons in each. Create a "course" of household or other tasks like loading or unloading a dishwasher, making and packing lunch for school, making a bed, and so on. Guess how long it will take to complete the tasks. Use a stopwatch to time the tasks. Closest guess to the correct time wins.

Reinvent the Calendar

How would you organize the 365 days of the year into smaller units or make your year have fewer than 365 days? What day will be the start of your calendar? What would you call the days, weeks and months? Maybe your "days" only come in pairs -- Even Day and Odd Day. What are the special days on your calendar? Will the calendar correspond to the phases of the moon or changes in season, or will it be organized by something random, like whenever someone loses a tooth?

Labyrinth

I never knew that mazes and labyrinths are not the same until I happened to be invited to the home of a friend who had a full-sized labyrinth on her property. As we walked it together, she explained that a labyrinth only has one path: you walk in toward the center and out again the same way. Mazes are meant to be confusing, full of dead ends and blind alleys, high walls or hedges, and twists and turns. Labyrinths are less frustrating but equally mysterious to a child, which is why they make a great palooza.

What's the Palooza?

Learn how to draw your own labyrinth. First, look at the examples of the labyrinths, opposite, which are the two most common types out of hundreds of variations. Labyrinths have a rich and varied history; they've been found on Greek coins and clay tablets, Roman mosaics and pottery, Swedish coastlines, medieval European cathedral walls and floors, Native American baskets and cliffs, Peruvian sands, Indian dirt, and English village greens.

Begin with the simplest labyrinth of all, the three-path (three-circuit). Look at the "seed pattern" below and copy it on a piece of paper at least 81¿2 by 11 inches. It's better to draw the seed pattern in the bottom half of the paper. Then it's a matter of connecting the dots and lines, as illustrated below. Once you've drawn your own, you can "walk" the labyrinth by tracing the path with either your finger, a pencil eraser, or a crayon or marker. (This is great to do in a restaurant with crayons and paper tablecloths.) It might take a few practice labyrinths before you get the hang of drawing the lines evenly enough to make nicely spaced paths, but that's part of the process.

After you're comfortable with the three-circuit labyrinth, you can try the seven-circuit, as illustrated below.

Extrapalooza

Sand and Land Labyrinths

Once you know how to draw a labyrinth with pencil and paper, you're ready for a larger canvas. Any wide open, level ground outdoors makes an excellent place for a three- or seven-circuit labyrinth with paths lined in small stones or rocks. If you're ambitious and energetic enough, make it really large and invite friends to walk it.

Your own backyard has labyrinth potential: try a simple three-circuit labyrinth by marking with chalk then cutting the pattern in the grass with a lawn mower. Driveways and sidewalks are great for chalk labyrinths of any size.

Next time you're at the beach, make labyrinths in the sand, using either a stick, your hands, a shovel, or even your feet.

Left-Hand Man

About 10 percent of the world's population is left-handed, and no one knows why. In some cultures, left-handedness is taboo, and left-handed children must write and eat with their right hands as if true righties. Lefties today are met with fewer cultural prejudices, but they truly do live in a world made for right-handed people. This palooza lets children explore the curious asymmetry of their own bodies and the inherent right-handedness they might never have noticed in everyday objects.

What's the Palooza?

Devote a day to left-handedness. Righties try to make their way through the day using their left hands the way they usually use their right hands. If you want to be really authentic, do it on August 13, International Left-Handers' Day. You'll realize how well trained our preferred hands really must be to do everyday tasks. Eating with a fork with your opposite hand feels awkward and can be messy. And writing with your opposite hand -- well, for most people, it's just sloppy. You'll notice right away how automatically you use your right hand when dashing to pick up the phone or flip on the lights. As hard as it may be to switch for the day, you'll discover how hardwired you are to your handedness.

Explore the house and study all the little things you never noticed were intended for right-handed people. Wear your watch on your right wrist (as most left-handers do). It's hard to change the time without taking the watch off -- the knob is on the wrong side! Play a game of cards with a standard deck. You'll notice that if you fan your cards in the left hand, you can't see the numbers. Now try writing in a spiral notebook. Ouch! Those books are definitely made for right-handed writers. Use a pencil to write. You'll see that our writing system, which reads from left to right, causes your left hand to get smudged with graphite as it continually rubs over what's just been written. Try using scissors or a can opener with your left hand. See how they're made just for righties? Make a list of all the things you can think of that favor the right hand. Even better to discover the rare objects that are easier to use with your left hand (a toll booth is one example).

Extrapaloozas

The Right Way

Here's where the 10 percent of you who are left-handed try to see how the other 90 percent live. You'll struggle with awkwardness when writing and doing other ordinary activities, just the way the righties do when trading places with you. Look for all the little ways to work with your right hand -- buttoning your shirt, tying your shoes, buttering your bread. You can gripe every other day of the year about tools and equipment being right-handed -- today's your day to live in the lap of right-handed luxury.

Leonardo da Lefty

Being a lefty isn't only about getting ink smudges all over your hand when you write. It means that you're wired differently -- the right hemisphere of your brain, instead of the left, is the dominant one. Left-handed -- and thus right-brained -- people tend to be creative and visually oriented, with exceptional spatial abilities. Whether you're left- or right-handed, stimulate the right side of your brain by looking closely at left-handed art. Examine the masterpieces of Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael and see if you find some quality or tendency of their work in common. Look at the works of Picasso and van Gogh and think about how the way their brains worked -- as well as their talented left hands! -- helped them develop such unique styles of painting. Look up the drawings of M. C. Escher, which demonstrate the incredible spatial sense found among many left-handed people. Give the right hemisphere of your brain a real workout by trying to draw spatially impossible shapes and staircases leading nowhere.

Go to www.artcyclopedia.com to view works by these and other artists.

Imaginary World

It takes a special gift of imagination to invent a whole world, fully realized inside your head. A child absorbed in the tiny details of their imaginary world is a wonder to behold.

What's the Palooza?

Build a fairy house! Among the most enchanting inhabitants of an imaginary world are the fairies. And while fairies certainly make it their business to stay out of sight, you can make your yard or front step or windowsill a welcoming place for these sly, shy creatures by making a house for them featuring all the fairy creature comforts.

Start with a lidded shoe box (the smaller, the better), so you can lift the "roof" off your house to arrange and decorate inside. Cut holes (in any whimsical shape) for windows -- fairies like natural, dappled light, so be sure to allow for a window on each wall. Cut a door opening at the front of your house, leaving one long side attached as the hinge side of the door. You may also want to make a back door, for a quick escape.

Take the top off your shoe box to work on your roof. You can have a flat roof decorated with leaves or bark, perhaps with a chimney or two made of twigs and bark. Or you can construct a pitched roof, by creating A-frames out of two six-inch twigs affixed with glue. Three or four A-frames ought to be enough support for your roof. The roof can be constructed of shirt cardboard cut to fit your A-frames, then decorated with leaves or bark like shingles. Or you can skip the cardboard and make the roof out of big pieces of bark, carefully glued to the A-frames. A twig chimney would be a nice touch. Be sure to glue the roof securely to the top of the shoe box at the bottom of each A-frame twig. Let this dry thoroughly before handling.

Back to the house. Find bark or leaves or evergreen fronds to glue to your house like big shingles. Leave enough clearance at the top of the house so you can set your roof on top. Use small twigs for window mullions; skeleton leaves hung just inside the window make nice curtains.

Speaking of curtains, what else is inside your fairy house? An area rug or wall-to-wall carpet made of moss? Perhaps there is furniture made of Popsicle sticks and bottle caps. Tablecloths made of flower petals. A handsome fireplace of chunky little rocks. Bowls or sconces made of acorn caps. A seedpod couch. A wall mirror made of a piece of mica. Use thick twigs as beams in the corners or across the ceiling (the underside of the shoe-box top/roof). Wander around outside gathering interesting small things and imagine how a tiny person might make use of them. The cozier and homier your fairy house, the better for your fairies.

Nestle your house in a quiet, rumpled spot in the backyard or tucked behind a pot in the garden. Because fairies need to wash and dry their delicate wings, be sure to provide a little pool for bathing, perhaps made from a shallow saucer, and a nice flat stone for drying in the sun. When you're not looking, of course.

You can also set your fairy house on the sill of an open window, where the fairies can spot it. Hang a garden chime made out of old silverware nearby -- fairies love the tinkling sound when the wind blows.

Extrapalooza

A Whole New Rock

Scientists are always discovering new things in the universe. What if you could "discover" a whole planet and its population? What is your discovery called? Where is this planet in relation to your own? Does it have gravity? What grows there? What are the inhabitants called? Maybe they're not "people," maybe they're "Ackz." What are their common physical features? How do they move or breathe? What do they eat? Can they see, hear, and smell, or do they have other senses we've never heard of? What language do they speak? What do their families consist of? Do they wear clothes?

Once you've thought a bit about these questions, try to fully imagine someone from this planet, perhaps someone just your age. Name him; imagine his family, his home, his history. Does he go to school? Does he have a pet? What is it? You ride a bike -- how does he get around his neighborhood? Name and describe his friends.

You can daydream for days about this planet and the beings you invent. Think about keeping a diary of this imaginary world. Write snips of dialogue using bits of alien language they speak. Think of adventures your young boy might have. Draw the planet. Draw a building or a vehicle on that planet. Draw the young boy you imagined. Draw his family. The more detail with which you imagine this planet and its inhabitants, the more real they will become! Go to www.space.com/spacewatch to get ideas about where your planet might be and what it might be called.

Photo-Essay

The photo-essay is a very twentieth-century form of expression that first came into prominence with the launch of Life magazine in 1936. Publisher Henry Luce assembled some of the most talented photographers working at the time to create a magazine where the stories would be told through photographs. Photo-essays uniquely show how life really is composed of small moments and intimate expressions -- and give us an opportunity to appreciate them.

What's the Palooza?

Create a photo-essay that tells a story by presenting carefully chosen, unposed photographs. You are the visual storyteller, taking several photos of your subject, from which you select the best, most interesting combination of photos to create your essay. Your subject can be an exciting event, like a space shuttle takeoff, or a historic event, like a big protest rally in Washington, or an ordinary event, like a visit to the dentist. It can be a story of a time and a place, like a day-in-the-life at a roadside fireworks shack on the day before the Fourth of July.

Whatever your subject, try to take photos that are natural, unself-conscious, almost ordinary in their matter-of-factness. You are a quiet observer of the goings-on, catching small moments that will help you tell your story. A photo-essay about your sister's dance performance might begin with a shot of her leaving her house or arriving at the theater. Instead of a perfect posed shot of her in her tutu, you catch her in front of a mirror with bobby pins in her mouth, as she scrambles to pull her hair up into a bun. You might also have a shot from the wings, where you show a calm, bored audience waiting for the performance, in contrast to the chaos backstage or in the wings. At the end, we see our dancer accepting a bouquet of flowers, happily embracing her proud grandmother, or asleep in the car, tutu and all.

Create an essay on a day in the life of someone you know. Other subjects for a photo-essay could be your family vacation, the construction (or demolition!) of a building, a sporting event, the hunt for a perfect Christmas tree, a visit to your big sister at college. It can be anything that bears a thoughtful, close look at the details that make up the whole.

Be sure to have plenty of film available because you'll need to take quite a few photographs to get enough of just the right shots to make up your story. Digital cameras are great, because you know on the spot if you have a good picture, so you don't have to develop a lot of so-sos. But any kind of camera is fine as you explore the art of photographic storytelling.

Once your pictures are developed, spread them out on a table and try to identify the few that vividly indicate what happened. Be on the lookout for little telling details -- unexpected expressions on people's faces, subtle body gestures, an odd feature of the physical surroundings. These details are what will make your photos distinctive, and tell more of the story than even words might have.

After you've chosen your photos, mount them in order on cardboard or dry-mount board with glue or spray adhesive. Then title and date your essay. Once you've created a photo-essay, you'll enjoy certain experiences by wondering how you'd tell the story in photos!

Extrapalooza

Small Time, Big Time

Practice the art of the photo-essay on very small, simple events. An essay on the school flag being raised. Or someone buying an ice cream cone. Or your dad reading the morning newspaper. Shooting these short, uncomplicated events will sharpen your eye for the juicy details of the bigger events you may want to describe in photos.

Board Game

You've probably been playing board games for most of your life without much considering how they are invented and constructed. When you create your own game, you begin to understand what makes a game tick -- and fun to play.

What's the Palooza?

Rework or recycle an existing game -- or invent something totally new. First, choose a theme, the topic or subject your game is built around. The theme of Clue is murder mystery. The theme of Battleship is naval war strategy. Think of a subject that interests you. Do you like horses? Maybe your game will be a horse-race game, with different breeds and great horse names, racing around the board to the finish line. Maybe you're a history buff -- Revolution might be all about heroes and villains and battles of the Revolutionary War.

What's Your Goal?

There are two basic board games. In strategy games like Monopoly, the goal is to gain control of the board by capturing or blocking the opponent's pieces, overpowering the opponent with your pieces, or trapping (and eliminating) your opponent. In race games like Candyland, you start at one point on the board and try to beat your opponent using the same or different paths to a finishing point.

Once you figure this out, you can determine what moves your game along -- dice, cards, a spinner, a timer. Or invent your own combination of mechanisms: the player rolls the die and only has a certain amount of time to figure out his options.

Decide how the players will interact with the game. Create identity pieces for each member of your family, either place cards with each of their pictures on them, or pieces that have some connection to the person -- a little plastic horse for your sister, a miniature telephone for Mom, a car for Dad. You may design and create cards if your game calls for them -- unlined index cards will do the trick.

The Details!

Before you design your board, think about how many people can play. Make enough cards or pieces for more than two players even if you're working on a game for only two players -- it will be frustrating later if you try to play your game with more than two people and don't have enough cards and pieces.

What rewards and hazards will make your game interesting, and work with your theme? A piece of gold collected when you land on one square; a spell in the quicksand when you land on another? Are there things that can turn the game upside down or suddenly put someone who was losing in a winning position? Life is filled with surprises -- your board game should have some, too!

The Board

Think about how your board will look and work. Maybe you want your board to reflect a route that snakes from one point to another. You might adapt the chessboard design in a clever way. Your board could be round -- or 3-D! Maybe you've created a game where the players work their way up and down more than one level.

The point is, the board for a board game can be anything you want it to be. Look at all the boards in your family's game cupboard for ideas, and recycle the boards and pieces for your own game.

To use an old board as the foundation for your board game, cut and glue sturdy paper to fit the old board. Sketch ideas for your board design on another piece of paper, then pencil it out on your actual board. Use markers or crayons to draw the features; you can also use stickers, or even images cut out from magazines -- imagine a basketball board game with the squares decorated with Sports Illustrated-style pictures of your favorite professional players.

The Name of the Game

Good games always have names that are either entertaining and vaguely descriptive (Pictionary, Smart Mouth, Boggle) or use a word that's part of the vocabulary of the game (Uno!).

If you've created a game where every square on the board is a famous painting, the game might be called simply Museum. That horse-race game? Maybe it's called By a Nose.

Remember that your game is a work in progress that you can test and refine and change as much as you like. The only way to see if your game is working is to play it -- a lot.

Extrapaloozas

New Old Games

If you're more of a reinventor than an inventor, try to put a twist on a game that already exists. Make your own deck of cards with photos of friends and family -- even pets! -- standing in for the usual king, queen, jack, and ace of the standard deck of playing cards. Make your own chess pieces out of Sculpey. Or use small plastic figures in place of the usual chess personnel -- a mixed squad of plastic dinosaurs or army men would work. Make a mancala game out of old buttons. Or make your Monopoly game local -- change the standard streets and landmarks to streets and landmarks from your own town!

Box It Up

To create a box for your game, use a sturdy, plain gift box you can design and decorate. If your game is an odd size, you can buy non-standard-sized plain gift boxes at paper goods stores. Create a logo for your game that appears on the box. Draw scenes from your game to "market" the appeal. That safari game might have a giant snapping crocodile featured on the box. Mark the name of the game on all sides of the lid, so you can tell what it is in a stack of games. Store pieces and/or cards in small, reclosable plastic bags. And make sure to include the directions and rules, either on a card (laminate it if you can, because it will get a lot of use!) or written on the inside of the lid. Make your directions simple and clear. Explain the game step by step, in logical order, being very precise with the words you choose. If you're sloppy with the language in the rules and directions, arguments are sure to happen! Test the rules on your friends and family to be sure they are easily understood. And don't forget to include a list of materials or parts of the game at the beginning of your directions, so the players know what they should be playing with.

Sensation

Actors often use a technique called sense memory when they want to re-create the sensory impression of a particular experience in their acting. The idea, as practiced and encouraged by legendary director and acting coach Lee Strasberg among others, is to take note of what you experience in everyday life by using all five senses and to commit those impressions to memory. This palooza is a bit of a twist on Strasberg's sense memory exercises and Blindman's Bluff.

What's the Palooza?

Explore the idea of trusting your senses and developing your sense memory.

Trust Walk (Ages 6-12)

One player is blindfolded and then led around a familiar room or area by another player, "observing" objects and spaces in the room with all available senses. Before tying on the blindfold, have the trust walker take in the room by sight. If it's the player's bedroom, look at the objects on the desk and bookshelves. What's on top of the bureau? Where are the windows, closet doors, toys, and other belongings? Tie the blindfold on and through a combination of both leading the player to an object and simply placing objects in hand, have the player make guesses as to what he is touching. Challenge the player to search the objects for clues that engage his memory. For instance, you put a book in the player's hands. That's easy, it's a book. But which book is it? The player has to think about the book in his hand -- is it hardcover and heavy or paperback and small? The player also has to think about which books are in his room. When he feels the book carefully for details, he notices a dog-ear at the bottom corner of the cover. Oh! That's Wringer, which he fell asleep reading last night, causing the bend in the cover.

Move the game to another area that the player has not had any time to "take in" beforehand. Is there a noticeable difference in the number of objects the player is able to identify? Use other senses besides touch. Are there objects that can be identified by smell or sound? Finally, extend the trust walk throughout the remainder of the house or even out of doors. Can he guess where he is? Can he identify objects, sounds, and smell? Reverse the player and leader roles. Talk about the idea of trusting your senses. How about trusting your leader? When you remove the blindfold you will realize more fully and appreciate all over again the colors, sizes, and shapes of the things around you, and your attention to the details in your surroundings will be sharpened.

Sense Memorizing (Ages 9-12)

Think about what happens when you're really hungry and someone mentions your favorite food. Your mouth might start to water because you have a vivid memory of how that food tastes. You have a sense memory for your favorite food, and your mouth is responding to that memory. Actors use sense memory to create realities in their scenes, training their senses to be heightened and aware so that when they are called upon to be or do a certain thing as part of a role, they are able to make it believable. The idea is that if the actor believes what he's doing on the stage is real, the audience will also believe it is real.

Whatever you're doing right now, decide to notice and "memorize" as many fleeting sense experiences as you can. A car passes by. You put your elbow down on the table. The phone rings. You take a bite of an apple. After you experience the real sensation, try to re-create what it felt like again a moment later. Can you close your eyes and re-create the feelings of the following situations using your sense memory?

Jumping into a swimming pool

Making a snowball without your gloves

Lying on the beach in the sun

Picking up a glass of ice water

Sipping ice water

Extrapalooza

Blindman's Bluff (the original, suitable for all ages)

Stand in a circle. One player gets to be the blind man first and stands in the middle of the circle, blindfolded. The blind man is gently spun around three times and let go to walk toward the other players. Upon reaching a player in the circle, the blind man tries to guess who it is by feeling the other player's face, hair, clothes, and so on. Guess correctly, and you're no longer the blind man. Switch places with the player you've identified. Play continues until everyone has had a turn at being the blind man.

On a Roll

Papier de toilette. Carta igienica. Toilettenpapier. Papel de tocador. Toilet paper by any other name is still just toilet paper. And you probably have plenty of it at home. If not, well, ahem, you might want to go out and get some, especially for this palooza.

What's the Palooza?

Invite the humble roll of toilet paper to come out and play. The wildly popular performance artists, Blue Man Group, have a rousing finale to their show that involves toilet paper. I don't want to spoil the experience for those of you who've never seen them perform, but I can tell you at least this much: the piece involves seemingly endless streams of toilet paper and lots of audience participation. And it puts a big grin on your face. This palooza celebrates T.P. and promotes an entire afternoon's worth (or better yet, a sleepover party's worth) of toilet-paper-themed activity. You can play this palooza alone, with a parent or sibling, or with three or four others in a small group. One small but important piece of advice: dispose of the paper in the garbage, don't flush it -- no one wants to gum up the works with too much papier!

Toilet Paper Wrap Art Ages (9-12)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude are artists famous for wrapping familiar objects in fabric to create sculpture that draws our attention to the objects in a new way. They started out in the 1960s wrapping small things -- bottles, cans, packages, doorways -- and moved on to much bigger things. They wrapped one of the famous bridges in Paris, the Pont Neuf, in woven nylon and rope (The Pont Neuf Wrapped, Paris, 1985). They wrapped the Reichstag in Berlin (Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin, 1971-1995). They wrapped trees with fabric and twine in Switzerland (Wrapped Trees, Project for the Foundation Beyeler, Collage, 1997). One gets the feeling that Christo and Jeanne-Claude view everything they see in the world in terms of how it might be wrapped!

Use toilet paper to create your own wrapped art à la Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Look for objects of unusual shapes and sizes to wrap. Wrap a table lamp (unplugged, of course). Wrap the television set (do this on TV Free week?). Wrap old toys or your bike. Try to wrap objects in different ways. Wrap tightly, swathe loosely, drape. Soon you will understand what intrigues Christo -- when an object is wrapped, how is it then perceived, on its own and in relation to what's around it? Does it seem to you to lose definition or to gain new qualities that you are seeing for the first time?

You can also do a human wrap, which Christo did with his 1962 Wrapping a Girl in London. Arrange someone in a pose and then wrap him with toilet paper. You see the human form in a different way when you hide the obvious details. You begin to appreciate the shape and the scale of the human body. Take photos of your creations. Create names for your wrapped artworks. Display them. See www.christojeanneclaude.net for pictures and descriptions of the works of Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

The Toilet Paper Web (Ages 6-12)

Players stand in a circle as far apart as the room allows. One player starts by holding on to the first couple of sheets of toilet paper and tossing the rest of the roll across the circle to another player. The second player catches the roll and, careful not to break apart the toilet-paper streamer, holds on to the end sheets before tossing the roll on to a third receiver. Play continues with the roll being tossed across the circle from player to player without breaking the stream, creating a web of toilet paper. Once the roll is completely used, play continues with yet more rolls of toilet paper, or, if the web is sufficiently big and strong, it becomes a kind of parachute. Raise the web parachute up and down, walk or skip around in a circle holding on to it, toss lightweight toys or objects into it -- a ball, comb, a small stuffed animal -- and toss them up and down. Raise the web up high. Let go of it and let it fall on top of everyone. Or raise it up and take turns running underneath it, changing places in the circle with another player. When ready to dismantle, see how many objects you can toss into the middle of the web before it breaks.

Toilette Couture (Ages 9-12)

Paper dresses were a huge fad in the 1960s. The Scott Paper Co. is actually credited with making the first paper dress in 1966 as a promotional item for its "Color Explosion" toilet paper and paper towels. Design and make toilet-paper dresses. Ball gowns. Miniskirts. Tight, Dietrichesque dresses impossible to walk in. Make accessories, like neckties, turbans, jewelry, shoes, scarves, belts, aprons. Have a fashion show. Or stage a photo shoot, as if creating a fashion spread for a magazine.

Invent-a-Saurus

Mix a fascination with wildlife, natural history, dinosaurs, and other creatures with the challenge of concocting your own imaginary animals and you get a palooza worthy of Michael Crichton.

What's the Palooza?

Invent your own land before (or after?) time. Create your own creatures and draw them, label them, categorize them, write a field guide for them. Cross dinosaurs you know (triceratops, tyrannosaurus, stegosaurus, brontosaurus) with other animal categories (mammals, reptiles, rodents, crustaceans, birds, fish) and see what you get. Have dinosaur picture books on hand as references, as well as an illustrated animal encyclopedia. Make lists of favorite dinosaurs and favorite animals and start making imaginative combinations that are fun to illustrate.

Take the Chinese menu approach and choose from different columns:

Column A Column B Column C Column D Column E

DINOSAURS MAMMALS BIRDS REPTILES FISH

f0 Brachiosaurus Elephant Ostrich Crocodile Angelfish

Diplodocus Rhinoceros Owl Gecko Blowfish

Iguanodon Tiger Parrot Lizard Eagle ray

Stegosaurus Whale Swan Snake Jellyfish

Triceratops Zebra Turkey Tortoise Seahorse

Mix and match the dinosaurs and animals to invent fantastical species. Stegojelly. Tricerasnake. Iguanoturkey. What would these dinorific animals look like? Are they big? Miniature? Outline the creations first in pencil, getting the basic shape down on paper. Then fill in detail. Is it scaly or smooth-skinned? Muscular? Does it have hair? Or feathers? If it has wings, can they flap? What do the teeth look like? Check out illustrator Robert Jew's Lizard Head, a painting of an iguana so realistic you can see every bump on the lizard's skin (www.aca demic.rccd.cc.ca.us/~art/jew.htm). Think about your invent-a-saurus's features in this kind of up-close-and-personal detail.

When your drawing is complete, go over your pencil marks with markers, crayons, or colored pencils. Because no one really knows what color dinosaurs were, you can use any color or combination of colors you can imagine. Play with stripes, spots, or swirls. Use fluorescent colors or crayons with shimmers and sparkles. In his painting The Yellow Cow, artist Franz Marc uses brilliant, dreamlike colors to get us to look at the familiar cow in a new way. Pull out all the stops on color and patterns as you create your finished work.

Extrapaloozas

Home Sweet Home

Imagine your creature's habitat and then create it. Is it a jungle? A desert? A woodland? Maybe it's a city with tall buildings and buses and elevated trains! What's the weather like? What does the vegetation look like? Is it marshy? What kinds of plants?

You can draw the environment to scale on a large piece of paper, then cut out your creature drawings and place them in their habitat. Better yet, create a natural-history-style 3-D diorama environment for your 'saurus. Get a big shoe box or other box and turn it on its side. Paint a background and foreground. Glue on bits of moss for groundcover or cotton balls for clouds. Use twigs or stones from outside to make your environment realistic. Then arrange your cutout creature inside this lifelike environment. Make up stories about the creature. Does he roam in herds like the iguanodon? Or is he a lone ranger like T-rex? Is he a predator? Herbivore? Does he swim? Fly? What if humans entered the picture? Have your creature interact with other creatures you invent in his natural habitat.

Field Guide

Use a school composition notebook to make a field guide of your own for your invent-a-saurus creations. Draw and label your creatures in the pages of the notebook, or make pockets inside the notebook to house the creatures you've drawn and cut out with scissors. Make notes in the field guide about the creatures' feeding patterns, mating habits, herding instincts, and defense mechanisms. Note color and size differences between males and females.

Starry Night

This palooza directs our gaze to the sky in search of the art and poetry there.

What's the Palooza?

Explore the nighttime sky and find the art in the stars. Translate what you see into images and words.

Take a look at Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night on www.vangoghgallery.com. This famous painting isn't an exact representation of the stars, but an expression of how they made van Gogh feel. It's a swirling tempest of a nighttime sky. Look at other van Goghs, like Starry Night over the Rhone or Road with Cypress and Star. What did he see when he looked at the night sky that took this distinctive form in his paintings? What do you see in the stars?

Start with a little stargazing. Choose a good viewing place and time: a clear night far from a city. If you live in a city, save this palooza for when you're on vacation, or hop in the car and drive to where the city glow won't disturb your view.

Turn off all yard lights and inside lights, then go outside with a pair of binoculars. Let your eyes get used to the dark while you're setting up -- it can take up to ten minutes for your eyes to fully adjust to the darkness. Spread a blanket on the ground, lie down on your back, and look up.

You've seen stars so often that you stop noticing them. Try now to really look at them. Let the sky full of stars wash over you and surround you. Think about the stars in relation to your five senses. What do they look like to you? Jewels? Pinpricks of light? Observe how they're grouped, how they shine. Note the words that come to mind about what you're seeing.

If stars were music, what would it sound like? Something light and tinkly, from the high end of the piano? Or complex and dramatic, a symphony of sound? Do stars have a scent? Have you ever tasted anything that reminds you of stars? If you could reach up and touch the stars, what would they feel like? When you get back inside, jot down any impressions you had while looking at the stars and any words that describe them. Think about colors, shapes, sounds, tastes, textures; use nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs.

Now, follow in van Gogh's footsteps and draw or paint a picture of the stars. Use the words you wrote down to decide what you'd like to express about the stars. You can use any colors and put the stars in any context. Perhaps when you think of the stars, you don't see a big sky filled with millions of tiny lights, but instead you imagine stars reflected in your own eyes. Maybe you'll paint only one star -- the brightest, or the one that most held your attention. Create a series of pictures, exploring different perspectives and forms, using different media, and hang them all together as a portrait of the stars.

Try writing some poetry about the stars. Start with a simple haiku, a nonrhyming poem that has three lines and seventeen syllables. The first line has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, and there are five syllables in the third. Look at your star word notes and see if there are some that seem to connect well. For example,

Bright stars glimmering

Against the dark sky at night

Are smiling at me.

Now play with what you've written to explore your impression in another way:

Bright lights simmering

In a dark pot of star soup

Want to lick the spoon?

Extrapaloozas

The Ultimate Game of Connect-the-Dots

Constellations are groups of stars that appear to form a recognizable pattern. Go to www.skymaps.com to download a free map of this month's sky. Search for the constellations that are best seen during this month. Once you get the hang of finding the constellations, make up your own.

Go stargazing and let your imagination run wild. Does that group of stars look like a rose? Another group might look like a buffalo. Now, name your constellation. Name it after yourself -- Rachel's Ring or Heather's Hat. Or give it a more poetic name, like Flower with Wilting Leaves or Erupting Volcano. Sketch your constellations and make a guide to your night sky.

Star Mythology

People have looked at stars and made up stories and legends about stars for thousands of years. Some myths use the stars to explain things on Earth; others try to explain how the stars got up into the sky in the first place. Ancient Babylonian mythology described stars suspended on strings that were pulled up in the daytime and let down at night.

According to Navajo myth, the stars came to be scattered across the sky when First Woman carefully took jewels (stars) from a blanket and arranged them in the sky to spell out the laws for the people. Coyote offered to help her, but soon became frustrated with the enormity of the job. Coyote tossed the remaining stars into the sky, destroying First Woman's message and throwing the world into chaos.

Make up your own myth about the stars. Tell stories using the constellations that you invented. Maybe the myth about your Rocking Chair constellation explains how it was put in the sky for weary space travelers to sit on in while in space. Or tell a fantastic story about how the stars came to be in the sky. Your story can be as offbeat or unusual as you want it to be.

Palio

This ancient horse race is run every summer in Siena, Italy -- oh, the wild mix of history and loyalty and passion and color! Every bit of cunning and sneakery is at work, which is what makes it a perfect palooza -- a contest of creativity and wit and will.

What's the Palooza?

Create a feverish contest between immediate family members, relatives within an extended family, or families in your neighborhood. The Palio, or "the banner," has been run every summer since the 1200s in Siena, Italy, a hilly city surrounded by walls and towers meant to protect it from the brutal attacks of enemy republics. Who knew that the battle inside the walls was the one to watch? The Palio is a horse race that is run among the city's official neighborhoods, or contrade, and it is a spectacle beyond belief. Every neighborhood has a symbol (the Ram or the Unicorn or the Eagle, for example), and everyone who lives in that neighborhood devotes all their intelligence and energy into fielding a capable horse and jockey for this annual race through the town's Piazza del Campo, on a rough dirt track, with rubbery rules that allow for last-second trickery and treachery. What fun!

Teams. Start by designating teams. If you're a small family, maybe each member of the family is a team and can invite a friend from outside the family to join him. Or you can pair up within the family, or have entire families be single teams. Choose a symbol for your team that represents the strength or virtue you'd like to stand for. You can use the Italian symbols for inspiration or make up your own: A lion, for strength and valor. A rabbit, for speed and agility. A pyramid, for mystery and longevity. Choose team colors and create a logo for your team with markers on butcher paper. This will be your team flag and the image that appears on any other team or fan paraphernalia you want to create -- T-shirts, hats, coffee mugs, bobble heads. Write a team motto!

Palio Maestro. One adult has to be the conductor of this little orchestra we call Palio. He collects ideas for the games from all the teams, creates the games (maps out races, devises rules, writes questions, and so on), then conducts the games. And after all that hard work, he is then treated royally at the Palio Gala. A fun-loving uncle, grandma, or family friend would be ideal for this job.

Banner. Decorate a pillowcase or a plain piece of fabric with each team's logo to create the winner's banner for the Palio. Use paint and scraps of fabric; incorporate logos with other colorful patterns. Get fancy! This is the fiercely fought for, much-coveted prize.

Food. Each team chooses a recipe for their signature dish. It can be themed, like a carrot cake or carrot casserole for the Rabbit team. Or it can be just a distinctive dish for which the team will be known. Each team should prepare their recipe to serve at the Palio Gala at the end of the contests.

Contests. Create a series of four or five games that are a mix of contests of physical skill, knowledge, and resourcefulness. A relay race that snakes a crazy route through your neighborhood -- with a banana for a baton. A tricky combination of a spelling bee and trivia quiz. A persnickety scavenger hunt for items involving the five senses -- and all beginning with the letter "P." A complicated game of international hopscotch. Assign each contest a certain number of points to be distributed among the teams. For instance, a the winner of a 20-point contest might receive 10 points, second place gets 5 points, third place gets 3, and last place gets 2. And make sure your games take into account the variety of ages of players a trivia/spelling challenge for an adult, for example, would be more difficult than for a nine-year-old. Take the time to create games that are clever and surprising -- or just plain nutty. After all the games are played and points tallied, a winner is declared.

Palio Gala. After the winning team proudly takes possession of the banner, all teams retire to the Palio Gala, where each team's special food is served. Turn this into a festive banquet. Decorate the table with each team's colors and logo. Serve fizzy punch and Day-Glo desserts. Good music is a must. Take pictures of the winning team with the banner for your Palio scrapbook, where you'll also stow photos and details of the annual Palio.

Copyright © 2004 by John Lithgow

Adopt-a-Soup Can

Hold on to your hats, this is a nutty palooza. But trust me, the kids will love it. Andy Warhol exalted sameness in his Campbell's Soup Can series. This palooza brings an individual can of soup to life and gives it a personality all its own.

What's the Palooza?

Choose a can of soup to adopt. Roam the soup aisle at the grocery store and read aloud the names of various kinds of soup. Pick a soup that tickles your fancy and bring it home to "live." Invent a name that suits your soup can's personality; think Beany Bacon, Alpha Beth Soup, Tommy Tomato, Charlie Chowder, and so on.

At home with the soup, make a birth certificate for it. Look at your own birth certificate as a sidelight. Include the soup can's name, date, time, and place of birth (date of purchase, and store name), and the name of its legal guardian (your name). Once the soup can is named and has proper documentation, invent the soup can's life story and personality traits. Then dress it accordingly.

To dress the soup can, carefully remove the paper label. Trace the outline of the label onto a piece of paper to make a can-sized "dress" pattern. Design and color the new dress (or pants, bathing suit, tutu, and so on) for the can using the pattern. Thinking of its personality, use the soup can's favorite colors and patterns. Stripes. Solids. Citrussy oranges and pinks. Businessy blues and grays. Don't forget to leave space to draw a face onto the paper. Outfit the can by taping on his new clothes. Add hair by attaching pieces of yarn to the top of the can with tape.

A soup can's accessories say much about his personality. Dress him up for a business meeting by adding a little necktie. Draw an umbrella and handbag for her. Or a baseball cap and glove for him.

What's your soup can like? She's a little bit shy, but loves Audrey Hepburn movies. He's always green with pea-soup envy. Does she socialize with other soups or prefer the company of mixed nuts? The idea is to make the can as interesting a character as possible. And to get her involved in your life! She comes to the table for meals. She helps with homework. She goes to ballet class and soccer practice. She may even go to school for show-and-tell. Be sure to tell how she got that dent below her ingredients list. It's quite a story.

Extrapalooza

Souper Can!

Souper Can is a soup-can superhero. He's got whatever powers you dream up for him. (And he's probably wearing a cape and lots of spandex!) Take photos or draw pictures of Souper Can doing outrageous superhero kinds of things. Use the photos or drawings to make a comic book of Souper Can's adventures. Souper Can lands on the roof of the dollhouse for an amazing rescue of a cat stranded on the second-story windowsill. Souper Can bravely cleans his plate of Mom's asparagus casserole. Souper Can discusses playground safety with the school principal. Souper Can looks under a child's bed with concern. Write funny captions or dialogue to go with the pictures.

Junk Garden

By planting in unusual objects, planting an entire garden in an old tire, or decorating a whole garden with quirky found objects, kids get to flex their resourceful and imaginative muscles. They also gain an appreciation for whimsy in the garden and for the earthly delights of a garden itself.

What's the Palooza?

Create a junk garden by incorporating the odd and unusual in the backyard, family garden, or outdoor terrace by using household items -- from metal buckets or work boots to red wagons and old chairs -- as planters or garden decoration. One person's old frying pan is another's dream ornament for a patch of scarlet begonias. A toy truck displayed on a rock just so becomes an appealing garden sculpture.

Choose a patch of ground in your yard or garden that can be designated as the "junk garden." How big a patch of ground you choose depends on the size of your property, of course, and how much space you want to devote in the yard for the activity. A minimum of one square yard is plenty to start. Mark it off with stakes and twine, twigs, sticks, and stones, or other objects you gather for the garden border. Use seashells, wooden blocks, dominos, board game pieces, or even plastic race car tracks.

Once the border is defined, the junk garden is ready to be planted. Plant objects only or a combination of objects and plants. You may want to plant your objects first, so as to avoid trampling the plants. Or you may want to get impatiens or petunias in the ground first, so as to invent creative displays around them with found objects. You can also skip real plants altogether. Go wild "planting" colorful cups and saucers you've collected at yard sales or plastic juice cups. Dig a little hole in the ground and "plant" a cup so that it is sticking in the ground about halfway. Or paint wooden spoons bright colors and plant them as flowers in your garden. Plant action figures, plastic animals, Barbie, you name it.

Plant items from the kitchen or basement such as a yardstick, an old boot, measuring spoons, or flatware. Be artful about the planting and think of interesting ways to combine objects and plants. Use saucers as backdrops for small plants. Make a perch for birds out of an old spoon tied tightly to a twig with rubber bands. Tend the junk garden carefully and water frequently. Change or move the objects as you collect new items or simply to redesign the garden.

Extrapaloozas

Chair Trellis

Look for interesting old chairs at yard sales and antique stands. Choose a chair that has the patina of age or might be painted a favorite color. Position the chair in a spot that will accommodate the kind of plant you wish to grow, sun-, soil-, and water-wise. Ask your plant store for recommendations or choose a vine such as honeysuckle, sweet potato, passion flower, or a flowering bean vine, and train the vine to climb the chair. Voilà. Chair trellis.

Tire Garden

Use an old tire to make a raised bed. Fill the center of the tire with good soil and plant a tomato seedling in the center. Decorate the tire garden with Barbie shoes or marbles or other found objects. Then make tomato sandwiches in summer.

Junk Garden Themes

Choose a theme. Go all natural and use only twigs and stones, bird feathers, leaves, shells, moss-covered stones from a stream. Or make the garden dinosaurs-only. Create an imaginary universe in the garden using dollhouse furniture, "fairy furniture" made from items you collect (pipe cleaners, Popsicle sticks, toothpicks, old crayons), or twig tepees. Choose plants by theme, as well. Plant basil, lemon thyme, mint, dill, and lavender in a "nose garden." Plant snapdragon, tiger lily, catnip, and spider plants for a "zoo garden."

Container Planting

If it holds soil, and something will grow in it, it's a garden. Plant something wonderful in an old work boot. Or an old cast-iron frying pan. Or a little red wagon. Follow potting instructions for container planting from your favorite gardening book or rely on your own green thumb (paying attention to drainage, using good professional-grade potting soil, and so on), and plant to your hearts' content. Try lavender in the boot. Begonias in the wagon. Use yogurt cup liners (with a hole punched in the bottom for drainage) for planting in mugs you collect in thrift stores and yard sales. Have a mug garden collection.

Flowers for Your Garden

For immediate results in the flowerbed, plant seedlings or small plants from the nursery. Try annuals such as nasturtiums, petunias, impatiens, or verbena. Sunflowers are easy to plant from seed, and you can see growth almost daily. Green peas, lettuces, and pumpkins are fast-growing vegetables. Hollyhocks and daisies, two old-fashioned perennials, also mix well in a junk garden.

Bridges

I've never outgrown my sense of amazement at the sheer audacity of a bridge. The idea of spanning an enormous body of water while appearing suspended in air by a few thin steel threads is magical. No wonder children -- and most adults -- are endlessly fascinated by bridges.

What's the Palooza?

An exploration of bridges, mind-boggling and mysterious -- think about them, design them, build them!

Make up a quiz entirely of questions about bridges: What is the longest bridge in the world? The highest bridge? The strongest bridge? The oldest bridge? What country has the most bridges? What are all the types of bridges? What are the great bridges of the world?

Once the quiz is finished, take a trip to the library or the Internet. In looking for quiz answers, you can find out about famous bridges around the world, the history of bridges, how bridges are built, what materials they're made from, and so forth. You can also find out about the dozens of types of bridges, including suspension, cantilever beam, cable, truss, swing, and arch, to name a few. Try to find an example of each kind of bridge in your search.

Now that you know something about bridges, start building bridges out of as many different common materials as you can think of: paper, sticks, stones, clay, blocks, Legos, wire, magnets, candy, cards, toothpicks, you name it.

Begin by sketching a simple bridge. Then decide what material would work best for that particular bridge design. An arched bridge might be built out of plasticine. A truss bridge could be made of Popsicle sticks, white glue or Scotch tape, and string.

One of the simplest of all bridges is made of an 8 1/2 x 11 inch sheet of paper and six books. Take the piece of paper and rest opposite ends on a stack of three books each. Here's where the mystery of science comes in: If you try to put a weight on this paper bridge, say a few pennies, it will collapse. If you fold the paper a few times, it magically holds the weight of the pennies.

If you're feeling ambitious, make a simple scale-model truss bridge, using toothpicks, glue, cardboard, and a marker. Go to http://www.yesmag.bc.ca/proj ects/bridge.html and follow the step-by-steps.

A terrific book all about build-it-yourself bridges is Bridges! Amazing Structures to Design, Build & Test by Michael Kline, Carol Johmann, and Elizabeth Reith. It's a great introduction to the whole wide world of bridges, with history, science, and lots of hands-on designing, building, and testing activities.

And check out www.pontifex2.com, featuring Pontifex II software, which allows you to build and test a bridge of your own design. Then you can use the 3-D graphics feature to view your creation from any angle, including "first person," where you're in the driver's seat of the test car.

Extrapaloozas

Travel Bridge