Table of Contents

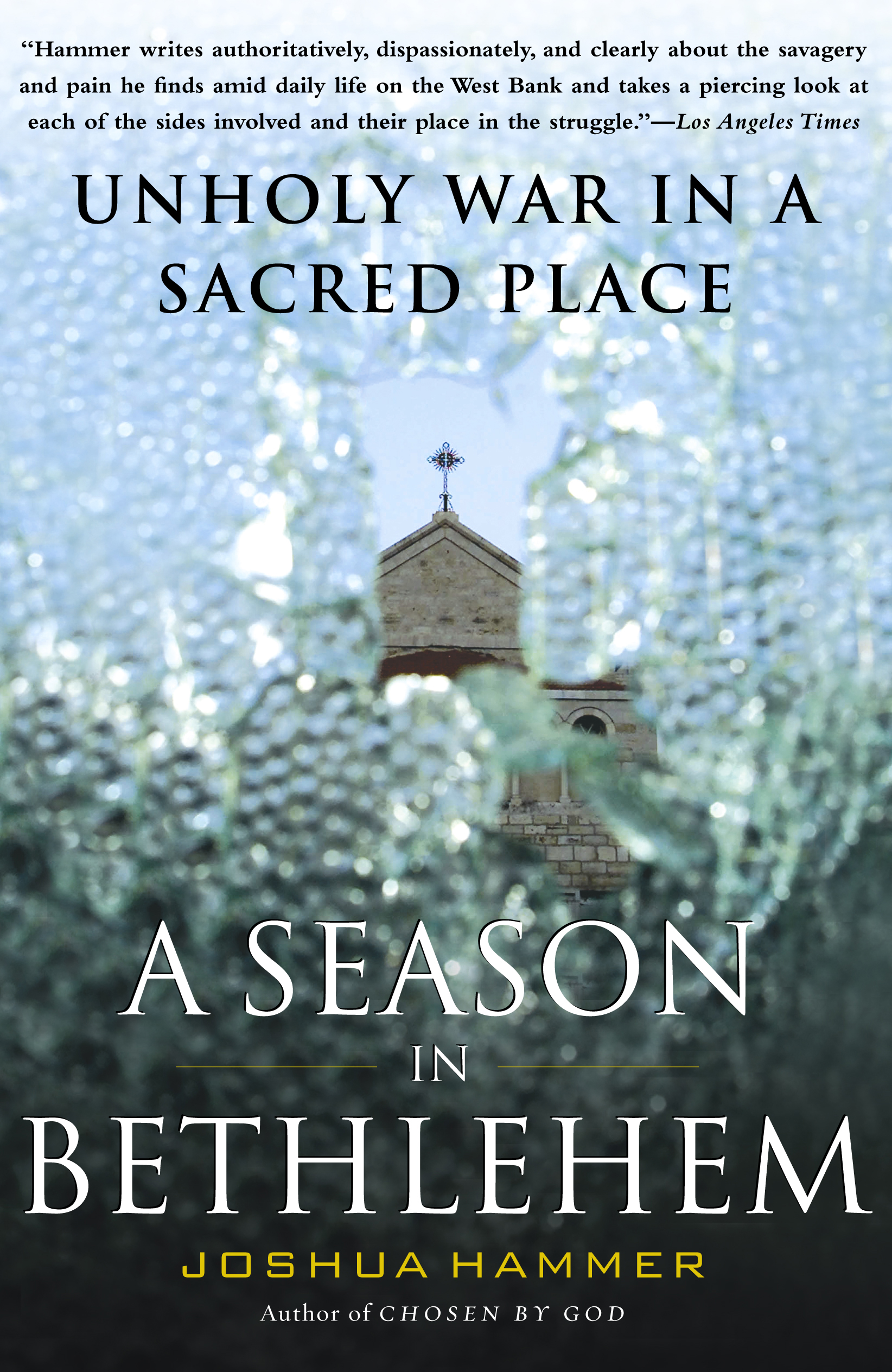

About The Book

A Season in Bethlehem is the story of one West Bank town's two-year disintegration, as witnessed by a reporter who was there from the beginning. Woven together from Hammer's own firsthand reportage plus hundreds of interviews, it follows a dozen characters whose lives collided on the streets of this biblical city. They include a Bedouin tribesman who rose to become the commander of Bethlehem's most feared and brutal gang of gunmen; the beleaguered governor, an opponent of the al-Aqsa intifada, who believed he had a mandate to stop the violence, only to discover that Yasser Arafat was undermining him; a Christian businesman who watched helplessly as his community was squeezed between Muslim militants and the Israeli army; an eighteen-year-old female honors student turned suicide bomber; and an Israeli reservist, son of a leader of the Peace Now movement, who wrestled with his left-wing convictions as he rode to battle through the predawn streets.

The narrative reaches a climax with a moment-by-moment recreation of the epochal drama that drew many of these characters together: the thirty-nine-day siege of the Church of the Nativity. A clear-eyed chronicle of deepening chaos and violence, in which Hammer lets the opposing sides speak for themselves, A Season in Bethlehem is both a timely and timeless look at how longstanding religious and political tensions finally boiled over in a place of profound resonance: the birthplace of Jesus.

Excerpt

He hadn't set out to be a martyr that day, his best friend Sa'ed Ahmad assured me. We were walking through the warrens of Aida refugee camp on a scorching afternoon in July 2002, and I had asked Sa'ed to re-create for me the day that Israeli troops had killed Moayyad al-Jawarish, thirteen, during a clash at Rachel's Tomb, a heavily guarded Jewish holy site located at the northern entrance to Bethlehem. I was investigating the life of a man named Ahmed Mughrabi, one of the most chilling figures in Bethlehem, the leader of a suicide cell that had sent a half dozen teenagers to kill and be killed in Israel. I had traced the story here, to these early days of the al-Aqsa intifada, when Moayyad's death had set in motion a terrible chain reaction of murder and revenge.

Sa'ed was a jug-eared boy of sixteen who lived with his parents in one of those indistinguishable alleys found in refugee camps all over the West Bank and Gaza -- a cramped quarter of ugly cinderblock buildings and kids playing with improvised toys such as unspooled reels of cassette tape that they find lying in the dirt. School was out for the summer when Sa'ed agreed to get into my car and head down the Hebron Road to Rachel's Tomb, a half mile away, to tell me about his friend's final hours.

With everything that's happened in the region since, it is not easy to remember the atmosphere back in those early days of the al-Aqsa intifada -- Moayyad was killed on October 16, 2000 -- when madness, excitement, and the lure of martyrdom swept up the children of the refugee camps. Nearly every day violent clashes erupted at Israeli military checkpoints thrown up at the border between Palestinian- and Israeli-controlled territory: the New City Inn and Qalandia junction in Ramallah, Netzarim junction in Gaza, the entrance to the Abraham Avinu Jewish settlement inside Hebron. Boys as young as five hurled stones and even firebombs at Israeli soldiers. Palestinian security forces and Fatah activists often stationed themselves at the periphery of the crowds of stone-throwing youths, according to many witnesses, firing their Kalashnikovs in the air in an effort to provoke the Israelis to shoot back into the crowds. At the same time, the beleaguered government of Prime Minister Ehud Barak resolved to squelch the new uprising quickly with an overwhelming use of force. The result was carnage: in the eighteen days between Likud Party leader Ariel Sharon's visit to the Haram al-Sharif -- what Jews call the Temple Mount -- on September 28 and Moayyad's final morning, ninety-one Palestinians were killed, a third of them children.

The hours and days leading up to Moayyad's encounter at Rachel's Tomb were especially bloody. Israeli Apache helicopters leveled the Palestinian Authority police headquarters in Ramallah in retaliation for the October 12 lynching of two Israeli soldiers who had made a wrong turn and wandered into the seething city by mistake. Israeli troops injured scores in clashes across the West Bank and Gaza that had erupted in protest over Israel's closure of the territories. Israel sealed off Haram al-Sharif, the third-holiest site in Islam, to Palestinians under the age of forty-five, determined to avoid a repeat of the rioting that had followed Sharon's provocative visit.

As Sa'ed remembered it, teenaged street leaders of Yasser Arafat's Fatah movement, which was then trying to assume command of the uprising, had called for a "scholastic demonstration" at ten thirty in the morning on October 16 at Rachel's Tomb. Sa'ed had been there three times before, once with Moayyad. The fighting had been fierce, he told me: Molotov cocktails and stones met with tear gas, a hail of rubber bullets, and occasional rounds of live ammunition. Moayyad's father, an unemployed pipe fitter, and his mother had begged him not to go down to the tomb anymore, but many of the boys in his school were going, and Moayyad didn't want them to think he was afraid.

It began as a typical morning. Sa'ed met his best friend at seven fifteen in front of Moayyad's house. Moayyad's grandparents were refugees from the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of Malcha who had fled their home in 1948 and had rented the place on the outskirts of Aida camp from a Christian family, thus avoiding the crowded warrens of the camp itself, which is home to about thirty-eight hundred Palestinian refugees. Moayyad appeared at the front door wearing black jeans and a blue tee shirt, the standard school uniform of the boys in Aida, as well as the prized Reebok soccer shoes he'd received from his parents for his thirteenth birthday. He was the goalie of the soccer team of the Beit Jala Basic School for Boys, the United Nations-administered school he attended on Aida's outskirts, and was considered an enthusiastic player. On his back he wore a black-and-gray vinyl knapsack stuffed with a half dozen text- and composition books adorned with cheerfully colored sports-themed covers. Sa'ed remembers that they had both an algebra and an Islamic studies test that day and that they talked about the possible questions on the examinations as they walked to their seven thirty class.

The boys passed through the blue metal gate of the Beit Jala Basic School for Boys, a two-story stone edifice set behind a high green fence. Knots of students gathered in the courtyard, kicking soccer balls back and forth and talking enthusiastically about the demonstration. Moayyad and Sa'ed spotted Ali Mughrabi, a tough fourteen-year-old from Deheishe camp and the leader of the Young Tanzim, the Fatah youth organization, at the school. Moayyad braced himself as Mughrabi approached him. "Are you coming today?" asked Mughrabi. Moayyad hesitated for only a moment. "Of course," he replied.

It is a stark and forbidding no-man's-land. Situated at the northern limits of Bethlehem, off the main road that runs from Jerusalem to Hebron, Rachel's Tomb is an emotionally charged flashpoint imbued with contradictory and irreconcilable meanings for each side. To Jews it is one of the most sacred sites in their mythology, supposedly marking the place where "Mother Rachel," wife of Jacob, lay down and died while giving birth to her second son, Benjamin, during her southward journey from Beit El to Jerusalem. Her spirit, the faithful believe, blessed and comforted Jewish captives as they passed by her burial place on the way to slavery in Babylon in 586 b.c. To Palestinians the tomb is a constant source of outrage, a reminder of their powerlessness, and a symbol of the broken promises of the 1993 Oslo Accords, which created the framework for a permanent peace agreement and a Palestinian state. The deal signed by Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat in 1993 left unresolved the final status of the Jewish holy sites inside Palestinian cities, including Rachel's Tomb in Bethlehem, Joseph's Tomb in Nablus, and the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron, although the Palestinian Authority did offer guarantees in perpetuity of access, prayer, and security for Jewish worshipers. Despite Palestinian assurances, the Israeli government moved to fortify all of the sites in the years immediately after Oslo. The Israelis argued that the Palestinians could not be trusted to safeguard this vulnerable part of the Jewish heritage; in the case of Rachel's Tomb, they cited such ominous developments as the published claim of Palestinian Authority officials in the mid-1990s that the tomb marked the burial site of an Islamic slave, not the revered Jewish matriarch. The Israeli army built a high wall around the modest, fifteenth-century domed structure that supposedly contains Rachel's remains. They added two forty-foot-tall watchtowers, narrowed the stretch of the Hebron Road that runs past the site, and stationed additional soldiers there to protect Jewish worshipers. Searches and identity checks of Palestinians who passed by the site increased, and as a result the commercial activity in the area sharply declined. In a part of the world where every square foot of land is invested with deep meaning, the Israeli Defense Forces also refused to withdraw from a few adjacent streets that the Oslo Accords had designated as "Area A" -- under the control of the Palestinian Authority. The abrogated withdrawal from the area meant that four thousand Bethlehemites would remain against their will under Israeli military occupation.

Rachel's Tomb became a magnet for Palestinian protests. The demonstrators expressed their anger over both the fortification of the tomb and other perceived breaches of the Oslo Accords by the Israeli government. In 1997 Israeli troops fired tear gas at five hundred students from Bethlehem University during a march to protest the groundbreaking on the new West Bank settlement at Jabal Abu Ghneim -- known to Israelis as Har Homa -- that sprawled across a barren hill between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. (Har Homa perfectly illustrates the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: although Israel forcibly expropriated land from some Palestinians to build the settlement, many other Palestinians sold their property willingly; in addition, several top Palestinian Authority officials obtained lucrative contracts from Israel to supply cement and other materials and services for the settlement's construction.) Two years after the Har Homa protests, a Palestinian was shot dead at the tomb after attempting to stab an Israeli soldier, a killing that precipitated three days of rioting. With the start of the al-Aqsa intifada, the clashes now occurred on a near-daily basis.

In Aida camp on that fateful morning two hundred boys, nearly one-third of the student body, poured out the gate of Beit Jala Basic School for Boys at ten o'clock. Moayyad walked arm in arm with Sa'ed at the front of the procession. Knapsacks on their backs, singing Palestinian national songs and thrusting their fists in the air, the boys were in high spirits. As they left the camp and entered the Hebron Road, they encountered busloads of boys and young men from the nearby Deheishe camp also heading for the demonstration. Ali Mughrabi waved to his brother, Mahmoud Mughrabi, who stood in the front of the lead bus, a plastic jerrican filled with gasoline at his feet. He had stuffed the rear pockets of his blue jeans with shoelaces, which he would use to fashion makeshift slingshots to hurl firebombs at Israeli troops. The cries of "Allahu akbar!" -- God is the greatest -- resonated from the buses as the Beit Jala Basic boys followed on foot toward the tall stone watchtower that rose over Rachel's Tomb.

"This is where we stood," Sa'ed told me, tensing visibly as we drew closer to the tomb. We were standing in the middle of the Hebron Road in the blistering heat, staring at the forbidding column. The clashes at the tomb were history now, but just the sight of it stirred up bad memories for him. I was nervous myself. The scene reminded me of those sniper alleys I had encountered in other war zones: burned-out, eerily deserted places where the sense of danger and nearness of death make the hair on your neck stand on end. Nothing much had changed since Moayyad and Sa'ed made their final trip here. The Israelis had sealed the street in front of Rachel's Tomb with cement blocks. A shot-up Kando gas station loomed on my right; a weed-choked, litter-strewn traffic median bisected the road. On the left, on our side of the street, two unfinished and abandoned apartment buildings rose beside neglected fields. Heaps of garbage and concrete rubble lay strewn across the road; the remains of a corrugated-metal blacksmith shop and a garage stood just a few feet from the watchtower. Everything was deserted, shut down. No one could drive past the tomb anymore in either direction, and anyone who tried risked being hit by a bullet fired by one of those Israeli snipers sitting there, faceless, behind bulletproof glass.

We moved back two hundred yards from the tomb and stood in front of the Hotel Intercontinental, a former Ottoman merchant's villa once known as the Jasir Palace. When the hotel opened in the spring of 2000, its Palestinian owners hoped that the five-star establishment -- with $200-a-night rooms and a graceful interior plaza in which fountains burbled beneath ancient shade trees -- would attract flocks of well-heeled Western and Arab tourists. Six months later the intifada began, and the area directly in front of the hotel became a war zone. Now the Intercontinental's ornate pink-sandstone facade was scarred by a bullet hole or two; its doors were locked, its interior dark.

The turnout for the demonstration had been big -- the biggest of the four that Sa'ed had been to, he told me. Four hundred boys from Bethlehem's refugee camps converged on the scene at ten thirty, and the violence began almost immediately. "There was a Ford Transit parked beside that big concrete block," he said, pointing down the Hebron Road at one of several ugly slabs that sealed the way. Two Palestinian police at a guard post behind the Hotel Intercontinental watched us with curiosity as we strolled around the former combat zone; this wasn't exactly a major pedestrian thoroughfare these days. "Just as Moayyad and I arrived," Sa'ed told me, "some shebab [teenagers or young men] from Deheishe camp raced up to the Ford, smashed the windows with stones, doused the interior with gasoline, and dropped in matches." As the flames shot in the air, the boys erupted in cheers.

The next two hours were chaotic. Two dozen helmeted Israeli soldiers took up positions in the center of the Hebron Road after the Ford was torched. Moayyad and Sa'ed hid behind a low cement wall seventy yards away from them, rising to hurl stones and chunks of concrete at the troops. A jeep roared up to the gas station and a half dozen soldiers leapt out, firing tear gas; the boys tossed the canisters back and hurled a barrage of stones, forcing the soldiers to take cover behind the jeep.

Mahmoud Mughrabi from Deheishe camp was, as usual, at the center of the fighting. A goateed and muscular man, he was clad that day in jeans and a white tee shirt, with a checkered kefiyeh (headscarf) around his neck. At twenty-five he was the most fearless of the demonstrators at Rachel's Tomb, the shebab acknowledged, and the most adept among them at making and hurling firebombs. Several times a week Mahmoud organized trips to the tomb, made sure participation was high, herded the youths onto public buses, and usually managed to persuade the bus drivers to waive the one-shekel fare because, he argued, the shebab were going to do "national work." Most of the boys preferred to remain in groups, but Mahmoud Mughrabi worked solo in the clash zone, creeping as close as possible to the Israeli soldiers, darting from tree to garbage dumpster to concrete wall, often scoring direct hits with his missiles. Today he carried his usual weapon, a soda bottle that he had picked off the street, filled with gasoline, and plugged with a crude fuse fashioned from a rag. Moayyad and Sa'ed observed him with nervousness and admiration as he hid behind a wall, out of sight of the Israeli soldiers, extracted a shoelace from his pocket, and twirled it around the bottle. He lit the fuse. Then he darted from behind the wall, swung the weapon over his head, and hurled it toward the Israeli position. The cocktail slammed against the pillbox and burst into flames, infuriating the soldiers inside.

The troops were everywhere now, perched on the Kando gas station roof, standing in the middle of the Hebron Road, creeping through the Islamic cemetery that lies behind a grove of pine trees at the rear of Rachel's Tomb. The shebab were conversing on their mobile phones, keeping track of the soldiers' movements, warning one another when and in which direction to run. At one thirty Sa'ed received a call from another Aida boy telling him that twenty soldiers were advancing quickly through the cemetery toward the field where he and Moayyad were lying low. He told Moayyad, "Time to go home." The two boys stood up simultaneously and ran in the opposite direction from Rachel's Tomb. At that moment a live bullet slammed into the back of Moayyad's head. Moayyad gave a little grunt, walked two steps, then fell down dead.

Sa'ed just stared. Moayyad lay face down in the grass, the blood from his fatal head wound trickling down his neck and back and staining the black-and-gray knapsack stuffed with his books. Sa'ed looked on disbelievingly. The boy started to weep, stroking his best friend's shattered skull. Mahmoud Mughrabi ran from his cover to Moayyad's corpse. His younger brother Ali joined him. Gingerly Mahmoud took Moayyad in both arms and carried him to a Palestinian Authority jeep waiting past the Bethlehem Hotel Intercontinental. Sa'ed ran home and, sobbing, told his parents about Moayyad's death. "After Moayyad died, I never went back to the clashes," he told me. "I couldn't bring myself to do it. He was like a brother to me." Mahmoud rode with the body to the government-run al-Hussein Hospital in Beit Jala, his tee shirt soaked with Moayyad's blood.

The city of Bethlehem sprawls across limestone hills rising twenty-five hundred feet at the edge of the Judean Wilderness, five miles south of Jerusalem, and lacks any natural landmarks such as rivers or lakes to form easy points of orientation. As you drive south out of Jerusalem on the Hebron Road, Route 60, you leave the carefully cultivated greenery of that city behind and begin to taste the breathtaking aridity of this part of the Middle East. The land is bleached out, windswept, and treeless except for a few swaying cypresses and gnarled olives. Past the thousand-year-old Mar Elias Greek Orthodox monastery situated on a hilltop to the left, past the fluttering Israeli flag, the gun-metal-gray watchtower, and the soldiers at the Hebron Road checkpoint, past the Palestinian taxis waiting on the other side, you arrive abruptly in front of Rachel's Tomb at an ugly concrete wall that blocks further movement south along the Hebron Road. Detouring left around the holy site, you pass an Israeli military encampment, surrounded by a low wall and barbed wire, that effectively cuts this part of Bethlehem off from the rest of the city. Beyond the camp lies Manger Street, curving through a newer part of the city, lined with shawarma restaurants, landmark hotels such as the Paradise and the Bethlehem, and many shuttered souvenir shops that, in better times, did a brisk business selling olive-wood religious scenes to some of the hundreds of thousands of tourists who visited annually.

You skirt the edge of a deep canyon, or wadi, to your left, that extends north toward the hulking apartment blocks and cranes of the unfinished hilltop settlement, Har Homa. Then you bear to the left and see, directly in front of you, the Old City clinging

to the slopes of the second-tallest hill in Bethlehem. It is a hive of twisting alleyways, thousand-year-old stone houses, archways, tunnels, souks, steep staircases, and churches of a half dozen denominations -- Syrian Orthodox, Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, Greek Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox. On a second hill just east of the Old City, separated from it by Manger Square and the smaller Nativity Square, stands the Church of the Nativity, the fortresslike complex built above the Nativity Grotto where Jesus is said to have been born and the center of Bethlehem's life for the past 1,650 years. The church perches on a promontory at Bethlehem's eastern edge; far below, in a wide valley, the largely Christian village of Beit Sahour extends east toward the emptiness of the Judean Wilderness. If you turn your back to the Church of the Nativity and the Old City and face west, you will see another long line of densely populated hills directly in front of you. This is the Christian village of Beit Jala and, just to the north, the annexed Jerusalem neighborhood of Gilo, built on land captured in 1967, separated from its Palestinian neighbor by another steep canyon.

Over the last half century the city has expanded across the surrounding hills and valleys. Except for the main Hebron Road, recently renamed for Yasser Arafat, there is almost no flat ground, and each turn opens up a new vista of dusty wadis -- pale brown eight months of the year, covered with a thin layer of grass during the winter rain. The wadis are peppered with flat-roofed homes built of blocks of Jerusalem stone, along with ubiquitous terraced fields of olives, one of the few crops that will thrive naturally in this semiarid climate. Besides the sense of sprawling verticality, the other powerful impression one obtains while driving around Bethlehem is the unfinished nature of the place. Half-built office complexes, hotels, and private residences seem to rise on every hilltop and at every turn in the road: exposed girders and steel supports emerge from the top floors of these windowless stone hulks, construction having stopped dead at the beginning of the al-Aqsa intifada. And of course there are the refugee camps.

Mahmoud Mughrabi's family lives inside Deheishe, the largest refugee camp in the Bethlehem area. Created in 1950, Deheishe is one of nineteen camps established by the United Nations in the West Bank and Gaza to take in thousands of Palestinian refugees who fled their villages and towns after the first Arab-Israeli war. Originally a sea of tents pitched on 160 acres donated by the Jordanian government, which ruled the West Bank at the time, the camp took on an air of permanence in the 1950s, when the United Nations constructed cinderblock huts to replace the tents. UN administrators introduced electricity and running water and hooked up sewer lines to the Bethlehem municipality. More and more huts arose, and refugees added second and third stories, gradually accepting that they would not be returning to their original homes in the near future.

Deheishe has been a hive of political activism since its creation. Every family inside the camp has at least one living member who vividly remembers the terrifying flight into exile, the loss of land, the chaos and sorrow of 1948; the Nakba -- catastrophe -- has fueled an uncompromising hatred of Israel and a dream, however unrealistic, of return. In many conversations with residents of Deheishe, I have heard that the land of Palestine extends "from [the Mediterranean] Sea to [the Dead] Sea" and that only the Jews who arrived before the 1948 war have a legitimate right to live there; the Poles, the Russians, the Ethiopians, the Americans who have immigrated in the years since then are illegitimate occupiers. During the first intifada the Israeli army surrounded the entire camp with a fence to prevent teenagers from throwing stones at passing cars; the only way in or out was through a guarded turnstile. The fence came down when the Palestinian Authority took control of Bethlehem in December 1995, but the anger hasn't dissipated. The twelve thousand refugees of Deheishe remain among the most politically active in the West Bank. The two most popular movements in Deheishe, Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, stood at the forefront of the first intifada and took an active role in organizing demonstrations at Rachel's Tomb during the second uprising. Later, only later, would come the guns and the bombs.

The camp sits on a hill that slopes sharply up from the Hebron Road. On a September day in 2002 my translator and I drove into the camp through the main entrance, marked by a huge mural depicting Ghassan Kanafani, the Akko-born Palestinian poet, playwright, and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine activist who was assassinated by a car bomb, allegedly planted by Israel's Mossad agency, in Beirut in 1972. We zigzagged through a maze of rutted alleyways, most of them barely wide enough for a single car to pass, each lined with two- and three- and even four-story cinderblock homes. The sky was visible only in slivers, cut up by a tangle of power lines. Minarets peeked above the shabby warrens, and political graffiti and paintings in a multiplicity of colors seemed to cover every inch of wall space: Palestinian flags, Israeli soldiers, Fatah fighters, Kalashnikovs, along with occasional English slogans such as "Occupation is a crime" and "Resistance ¿ terrorism." Old men wearing the traditional Arab kefiyehs gossiped in doorways. An army of schoolboys in starched white shirts and black pants headed to class; their paths crossed those of schoolgirls, clad in white-and-green uniforms and white headscarves, known as hejab, walking in the other direction.

Yusuf Mughrabi, Mahmoud's father, met me at the gate of his borrowed rooms in the center of Deheishe. He was a personable bear of a man with a broad, melancholy face, a prominent Roman nose, and a salt-and-pepper beard. He thumped around on a prosthetic right leg. He had lost his limb during the Six-Day War, he told me, when he went to look for the remains of a downed Israeli fighter jet near the Mar Elias Greek Monastery and stepped on a land mine in a field. Mughrabi now spent his days crafting wooden furniture in the courtyard of his quarters and brooding about the tragic course his family's life had taken since the start of the intifada.

The toll was nearly unfathomable. When I met him, one son, Mahmoud, was dead, two were in Israeli jails, and the remainder of his family -- two other sons, a daughter, his wife, and the wife of his son Ahmed -- were homeless. After his eldest son, Ahmed, became the organizer of the Deheishe suicide cell, believed responsible for the deaths of eighteen Israelis, Israeli troops destroyed his own place, which he had purchased and remodeled with ornamental gates and mosaic floors and a small landscaped garden in 1997. As he led the way across the courtyard to his rooms, Mughrabi told me that the United Nations had promised to give him eighteen thousand dollars to rebuild his house, but he guessed that it would require more than four times that amount to do the job right. So for now he was stuck where he was. The only personal touches on the otherwise bare walls were two framed photographs of Ahmed on his wedding day in December 2001 -- Ahmed was already assembling bombs in a workshop inside the refugee camp by the time of his marriage -- and an almost life-sized poster of Mahmoud, caught in the act of hurling a firebomb in front of Rachel's Tomb.

We sat on cushions on the floor in Yusuf's living room. He took off his prosthetic leg and stood it in the corner, and he rubbed the stump periodically as we talked. Yusuf's wife, a strikingly beautiful, dark-skinned woman in her fifties, with a blue-henna dye mark on her forehead that indicated her Bedouin origins, brought in coffee and a tray of fruit and then, at my invitation, joined us. Deheishe residents had told me that the mother of the Mughrabi boys had shown up at Mahmoud's funeral in December 2000 -- female appearances at funerals are a rare occurrence in Palestinian Muslim society -- and fired a Kalashnikov assault rifle in the air. "It was a pistol," she corrected me, as she fingered her rosary beads. "I fired seven shots." Mahmoud's parents had initially turned down a ten-thousand-dollar check proffered to them by representatives of the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein as compensation for the loss of their son; Yusuf Mughrabi told me nobody should expect a financial reward for such a sacrifice. But neighbors had prevailed upon them to accept the money, and they had used it to build a second-floor apartment for Ahmed in the family home in Deheishe. "Then the Israelis came and blew it up," Yusuf said.

Omar, the Mughrabis' six-foot-six-inch, seventeen-year-old son, also came in briefly. Like many other siblings in Deheishe camp, the Mughrabi sons had been deeply divided about the uprising when it began in September 2000. Mohammed, now twenty-one, and Omar had decided after a couple of trips to Rachel's Tomb that the stone-throwing and firebombing would lead them nowhere except perhaps to the cemetery. The other three boys -- Ahmed, Mahmoud, and Ali -- went to confront the Israelis as often as they could. Omar told me that fierce arguments would break out among them over dinner at the Mughrabi home. "Ali believed that we had to fight 'by any means necessary,'" Omar told me. "I thought he was making a mistake and I told him so." Ali was only fourteen at the time; within a year he would be building bombs with his brother Ahmed in a Deheishe explosives factory. The lives of Omar and Mohammed had followed a different course: Omar now studied heavy equipment maintenance at a vocational school in Bethlehem, and Mohammed worked for his uncle, Yusuf Mughrabi's half brother, at a supermarket the man owned on the Hebron Road.

I wondered whether Yusuf Mughrabi felt he bore responsibility for the disaster that had befallen his family. Palestinian acquaintances told me that even before the al-Aqsa intifada Yusuf Mughrabi had earned a reputation in Deheishe as an angry man, a revolutionary, filled with uncompromising hatred toward Israel. They also told me that he had driven his children to Rachel's Tomb and had wished them good luck as they headed off to throw firebombs and rocks at Israeli troops. Yusuf denied it. "I could not prevent them and I could not support them," he told me. "It was their decision." In several visits to Yusuf Mughrabi over the next months, I found him to be a compassionate man, extraordinarily warm and welcoming, professing measured political views; at one point he told me that "Israel needs another man like Yitzhak Rabin."

But it was hard to discount that awful family history. His half brother, the supermarket owner, offered a harsher view of Yusuf when I met him later at his thriving establishment on the Hebron Road. He told me that when Yusuf came back to the Palestinian territories in 1996 after twenty-nine years abroad, he was still mouthing the slogans of his youth, still talking of war while everyone else was concerned with making money. "Yusuf didn't understand the game," the half brother, also named Mahmoud Mughrabi, told me. "I told him it's a different time now from 1967; it's no time for revolution." Yusuf Mughrabi, the uncle told me, seemed to encourage his sons' most nihilistic impulses. "He was careless towards his kids. He couldn't control them," he said. I suggested that the loss of his leg as a teenager may partly explain the passions that drove him, but his brother assured me that it was the aftermath, the horrific journey that followed, that shaped his character -- and those of his sons -- more than the accident.

Yusuf Mughrabi, the grandson of a Tunisian immigrant to Palestine and his Palestinian wife, was born a refugee in Hebron in 1950 and moved to Deheishe with his family ten years later. Soon after the mine blast that tore off his leg, he traveled to Amman, Jordan, to be fitted with an artificial limb. There he resolved not to return to the Israeli-occupied West Bank, and he subsequently joined the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, part of Arafat's Fatah movement, which the Palestinian leader had set up with other exiles in Kuwait in 1958 to wage a military struggle against Israel. Over the next decade and a half, the Fatah leadership dispatched Mughrabi to do clerical work in medical clinics in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. In 1973 he and his wife moved from the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp on the outskirts of the Lebanese capital, Beirut, to the Ayn al-Hilweh refugee camp in the port of Sidon. Ahmed was born there the next year, and Mahmoud arrived in 1975. Then came Mohammed in 1979 and their only daughter, Dareen, in 1980.

Disaster soon followed. Ayn al-Hilweh was one of a number of refugee camps in southern Lebanon considered by Israel to be guerrilla strongholds of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the umbrella group of armed factions chaired by Yasser Arafat, whose Fatah movement constituted the largest number of fighters. After a series of deadly mortar and rocket attacks launched against the civilian population of northern Israel from southern Lebanese bases, a massive Israeli force swept across the border on June 6, 1982. The stated aim of the invasion was to drive twenty thousand Palestinian militants out of southern Lebanon, but Defense Minister Ariel Sharon would ultimately order his troops and tanks to advance all the way to Beirut. Gunboats shelled the refugee camps from the sea; warplanes strafed everything that moved on the roads -- passenger cars, pickup trucks, donkey carts -- and bombed the camps indiscriminately, according to reporters and United Nations officials at the scene. More than twenty thousand people, most of them civilians, are believed to have died. The battle inside Ayn al-Hilweh went on for two weeks. Israeli troops arrested Yusuf Mughrabi along with the entire staff of the health clinic; they blew up his house and forced his family to seek refuge from the bombing in basement shelters filled with hundreds of terrified refugees. "We lived in total darkness, without even a flashlight and only water and stale bread to eat," remembered Imm Ahmed (mother of Ahmed), as Yusuf's wife is known respectfully after the name of her eldest son. "Everybody was shouting for ten days continuously. A decomposing body of a woman lay on the floor." The family emerged to find the camp flattened and corpses flung about the ruins. Yusuf Mughrabi had vanished. For his family the effect was profound. "The kids started feeling the pain and bitterness of occupation early in their lives," their mother told me. "They saw their house, school, clinic, and camp destroyed, all destroyed. These memories were kept inside their heads, and nothing could ease it for them."

Released from Israeli custody after a week, Yusuf Mughrabi located his family in the ruins of Ayn al-Hilweh and slipped his wife some money. Then he fled to Beirut and jumped on a rickety boat with six hundred Palestinian guerrillas bound for Port Sudan. Yusuf's vessel was the first ship to leave Lebanon as part of the Palestinian Liberation Organization's withdrawal from the country negotiated by the United Nations; Mughrabi had no passport, no papers, and no idea of what the future held for him. "My morale was very down," he told me. Sudanese authorities reunited Yusuf with his family in a dusty refugee camp about ninety miles outside Khartoum, but it was just a way station. Under the terms of the negotiated withdrawal from Lebanon, Arab governments agreed to take in the exiled fighters and activists from the Palestinian Liberation Organization. But fearful that the exiles would be a destabilizing force, the Arab governments dispersed the Palestinians and their families to "military camps," often in remote and undeveloped corners of the country where they would not pose a threat.

The Mughrabi family's first home was a grass-roofed mud hut in Sinkat, a market town of ten thousand people in a drought-stricken corner of northeastern Sudan. The local tribes wore nothing but loincloths, carried spears and knives, and still practiced ritual scarification with razor blades. The town had no electricity and no running water, and Mughrabi, his wife, and their children lived alongside fifty Fatah fighters who were supposed to spend their days in military training but in reality ended up idling away their lives. To supplement his one-hundred-dollar monthly Fatah salary, Yusuf Mughrabi built a crude wooden boat and fished for his family in the nearby Red Sea; his children attended government schools alongside Sudanese children, picking up tribal languages along with their Arabic. After seven years there a dispute developed between the PLO and the Sudanese government; the PLO leadership ordered Mughrabi and his family to uproot themselves again, this time to the Libyan oasis of Kufrah in the middle of the Sahara. Just outside of Kufrah lay the desert, four hundred miles of nothingness in every direction. Periodic sandstorms would howl across the oasis. The sense of remoteness, the boredom, was overwhelming. Ahmed Mughrabi applied to study chemical engineering at a university in the port city of Benghazi, but, according to his father, the college administrators rejected him and told him that if he wanted to attend college, he should wait until he went home to Palestine. It was a crushing disappointment. "The housing in Libya was better than in the Sudan, and we had water and electricity," Yusuf Mughrabi told me, "but psychologically it was much more difficult."

The family endured seven more years in Kufrah. Ahmed and Mahmoud grew into adults there, having experienced no other life since their childhood than the harsh regimen of military camps in desolate surroundings. At the end of December 1995 the PLO leadership informed Yusuf Mughrabi that he and his family could return to the Palestinian territories under the terms of Oslo. "I felt like I could be a human being again," he said. Shortly afterward he traveled with his eldest son, Ahmed, by bus one thousand miles to Rafah, on the border between Egypt and the Gaza Strip, to lay the groundwork for the family's homecoming. But their ordeal was not yet over. The Israelis denied Ahmed Mughrabi entry, and he lived in a refrigerator carton in the no-man's-land between Egypt and Gaza for two months while his father sorted out the paperwork. Another eight months passed before Israel granted entry permits to the rest of the family. Then the Libyans refused to allow Yusuf Mughrabi's five other children to cross into Egypt without their father, forcing him to make the two-thousand-mile round trip across the Sahara to retrieve them and his wife. Reunited in the Rafah refugee camp in October 1996, Yusuf embraced his family and told them that their decades in the wilderness had ended at last. "This is your homeland," he said. "Nobody can kick you out of here. You can even cut down your almond trees and nobody can tell you that you're not allowed to do this. This place belongs to you."

Ahmed Mughrabi's wife, Hanadi, came into the room. She was a round-faced, softly pretty woman with doe eyes and three prominent beauty marks on her cheeks. She exuded an air of vulnerability and sweetness, but as we talked, I could detect a steely self-confidence and sharp intelligence. She had graduated the spring before the outbreak of the intifada with a degree in Arabic studies from Bethlehem University, and she spoke some English; the mere fact that she approached me to talk about her husband without being asked was a sign that she had been more influenced by Western culture than most Muslim women in the West Bank. I asked her if she had been able to speak to Ahmed Mughrabi since he had been arrested and charged with being the leader of Deheishe's suicide cell, and she told me that she had recently been to see him at a hearing at the Israeli military court in the settlement of Beit El, near Ramallah. During a lunch break she had forced her way through the crowd and approached an Israeli soldier standing guard in front of the room where Ahmed was being held. In passable English she had introduced herself as Ahmed's wife and demanded that he let her see her husband.

"Aren't you a human being?" she asked him. The guard relented. "He was inside a cage, with two meters between us, and my mother and three other soldiers present in the room. We told each other we loved each other, we talked about our families, and he told me, 'I'm going to be here in prison for not more than two years. They have to let me out, because this is our land, and they are intruders.'" When I told her that the Israeli authorities had rejected my requests to visit Ahmed Mughrabi in Nafha prison in the Negev Desert, she replied that she wasn't surprised. "The Israelis are worried, because they know that anyone who meets Ahmed comes to love him," she said. Ahmed Mughrabi had stunned those in attendance at his Beit El hearing by launching into a defiant speech that was reported in al-Quds and other Arabic papers. Pronouncing the Israeli court "void," Mughrabi had told the judges, "You should be sentencing the ones who killed my brother Mahmoud, demolished my home, and scattered my family." Then the tall, bearded militant declared, "You have shut down hope for the future. If you were in my place, you too would have fought against the state of Israel."

After the Mughrabi family returned to the Palestinian territories in 1996, the National Security Force hired Yusuf Mughrabi as a border guard in Rafah. His son Ahmed went to work for the same force in Ramallah. Mohammed, still a teenager, found a job driving a tractor on a farm in Jericho, and Yusuf's half brother hired Mahmoud to pack bread at his bakery in Deheishe camp. (He would later expand his business to include the supermarket as well.) In 1997 Yusuf secured a transfer to Bethlehem with the rank of major in the National Security Force. The family pooled their resources and purchased a house on a ridge at the summit of Deheishe, with sweeping views of the Judean Wilderness. Thirty years after he had left the West Bank, Yusuf Mughrabi was back where he had started.

Yet the Mughrabis struggled to find a place in the community. Mohammed Laham, a longtime Fatah leader in Deheishe who spent fourteen years in Israeli jails, welcomed the family when they arrived and tried to help them integrate into the tightly woven fabric of Deheishe society. "The Mughrabis were isolated. They had no tribe, no real family, no money, and no friends," said Laham, a wiry, tough-looking man in his late forties who has served as a godfather to two generations of Fatah activists in the camp. "They were complete outsiders, and they were desperate to find acceptance," Laham told me. Yusuf Mughrabi's half brother Mahmoud, who had not seen Yusuf or his family in three decades and had spoken to them only rarely, also did his best to make the Mughrabis feel at home. "[Yusuf Mughrabi] was full of resentment; he had an inferiority complex," Mahmoud said. "He wanted to distinguish himself from his other brothers, who had been successful in business. So he became a haj [made the pilgrimage to Mecca] and stuck with this idea of revolution."

Yusuf Mughrabi vehemently rejected his brother's optimism about the peace process. He was disheartened by the unchecked growth of Israeli settlements, the harassment at checkpoints, the curtailing of Israeli entry permits issued to Palestinian workers, and, above all, the bloody clashes of September 1996, which started when Israel opened an archaeological tunnel near Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque. Seventy-five people, most of them Palestinian, were killed in three days of rage across the West Bank and Gaza. Convinced that the Oslo Accords were meaningless, Yusuf Mughrabi said that there would never be a Palestinian state and spoke often about the inevitability of war. His brother chastised him. "Stop playing this old game," he said. "It's time to move on."

Yusuf Mughrabi's sons also had a hard time adjusting to their new community. Mahmoud Mughrabi lasted three months at his uncle's bakery, quarreling constantly, demanding pay raises, even threatening his uncle. "He resented the fact that we were doing well and his family was not doing well," his uncle told me. "He wanted to have everything at once -- a house, money, and standing in the community. I told him it had taken me years to build what I had." Like his father, Mahmoud seemed insecure, yearning for recognition. Mahmoud Mughrabi lifted weights obsessively; he also turned to Islam, an unusual path in secular Deheishe camp, where the Islamic fundamentalist groups Islamic Jihad and Hamas have never gained a foothold. Mahmoud's older brother, Ahmed, became even more devout, swearing off cigarettes and liquor and praying dutifully five times a day; friends suspected that he was considering joining Islamic Jihad. The National Security Force sent him to Jericho to become a trainer, considered a prestigious position, but he quarreled with his colleagues and angered the powerful head of the National Security Force, General Haj Ismail, who had spent years in Jordan and Lebanon with Ahmed's father. Banished to a lowly job in Hebron, Ahmed quit the force.

Ahmed and Mahmoud tried to put their lives on track. Although the unemployment rate in the Palestinian territories was near 50 percent in the late 1990s, both brothers found steady jobs connected to the tourism industry. Ahmed built and maintained cable cars for the new Téléphérique and Sultan Tourist Center, a gondola system linking the ancient city of Jericho with the Mount of Temptation, the site of a Greek Orthodox monastery. The work was dangerous, requiring Ahmed to hang several hundred feet off the ground, but it paid the equivalent of four hundred dollars a week -- a considerable income in the West Bank. Ahmed's religious commitment weakened, his uncle says. "Ahmed started making money; he got a taste of this life; he started growing his hair longer; he was becoming a modern boy." Mahmoud found a job cutting stone and laying tiles for a Bethlehem construction company that had European Community and UNESCO contracts to rehabilitate the Old City as part of the $300 million Bethlehem 2000 Project. Later he looked for a job at the Bethlehem Hotel Intercontinental near Rachel's Tomb. The manager promised Mahmoud an entry-level position if he graduated from a hotel management course. Mahmoud would finish cutting stones and commute five times a week to class at the prestigious Talitha Kumi Academy in Beit Jala. He told his friends at Deheishe that he loved the new hotel and that he was excited about the prospect of working there. At the same time, his uncle told me, Yusuf Mughrabi's uncompromising views exerted a powerful influence on his son. "Mahmoud was a good worker but he was confused," says his uncle. "He was always pulled in the other direction."

That other direction led straight to Rachel's Tomb. "Mahmoud was very nationalistic, he got very carried away," said Basel Afandi, twenty-four years old, a Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine activist in Deheishe camp. "He'd yell to the kids 'Let's go! Let's go,' on the way to Rachel's Tomb. He was always recruiting kids in Deheishe to go to the checkpoint and always the first to carry away the wounded." The biggest clashes took place on Fridays, when teenagers would congregate around Mahmoud in front of the al-Kabir Mosque at the Deheishe camp entrance after midday prayers and pack onto buses for the mile commute to Rachel's Tomb. Mahmoud's bravado -- and hatred of the Israelis -- seemed to grow after Moayyad al-Jawarish's death. At a Friday clash two weeks later, Samer Afandi, Basel's seventeen-year-old brother, watched in amazement as Mahmoud launched a firebomb at an Israeli pillbox sheathed in camouflage netting, then took off down the Hebron Road pursued by four dozen angry soldiers. Mahmoud clambered to the roof of a nearby abandoned building and rained down bricks, chunks of concrete, and even an empty water tank on the soldiers, smashing the hood of an Israeli jeep. "Mahmoud was fearless," Samer told me. "He always went further than anybody else."

The day before Mahmoud Mughrabi's first, and last, guerrilla attack against Israel, Moataz Taylach, fifteen years old, became the third young protester to be shot dead by an Israeli soldier at Rachel's Tomb. A stocky ninth grader who liked horseback riding and breeding pigeons on the roof of his house in Deheishe camp, Moataz was struck in the head with a rubber-coated steel bullet during a Friday demonstration on December 8. Mahmoud carried the fatally injured boy to an ambulance, berating the driver for not bringing the vehicle to the scene fast enough. He was angry and depressed at dinner that night, telling his father that "they're trapping each one of us."

On Saturday morning Taylach's funeral procession left the al-Hussein Hospital in Beit Jala and proceeded to the al-Kabir Mosque, a domed octagonal structure made of pink and white blocks of Jerusalem stone and sandwiched into a small square just inside the camp's main entrance. The imam said a prayer for the dead. Then six of Taylach's classmates from the Iskander Khouri United Nations School in Beit Jala and two of his brothers bore his Palestinian flag-wrapped body on a stretcher to a new martyrs' cemetery that had been consecrated at the beginning of the intifada in the village of Irtas, just south of Bethlehem. A cold rain began to fall, and thick droplets of water splattered on the waxen face of the dead boy, running down his eyelashes and moistening his colorless lips, which were curled into a faint smile. Hospital workers had tightly wrapped the top of his head with white cloth, hiding the gaping wound in the back of his skull. Mahmoud Mughrabi led five thousand mourners along a winding road at the top of Deheishe camp heading south above a deep chasm filled with a dense gray mist that parted occasionally to reveal an old Roman Catholic monastery far below. "Shaheed [martyr]," Mahmoud shouted, addressing the dead boy, "we will continue the struggle. Martyrs, we will continue to Jerusalem!" Soaked and freezing, the procession clambered up the steep path that led to the martyrs' cemetery, a bare patch of ground surrounded by a few scraggly olive trees.

Taylach's plot had been dug the night before, next to the grave of another Deheishe camp martyr, Abdul Kadr Abu Laban, who had been shot dead on December 5. The gravedigger removed the stone slabs that had covered the earthen pit, and the rain quickly turned the bottom into mud. Mohammed Laham and Mahmoud Mughrabi stretched a tarpaulin over an adjacent olive tree, partially shielding the grave. They gently lowered Taylach's corpse inside, replaced the slabs, and slathered cement from a plastic bucket over the stones. The crowd watched intently, the only sound the scraping of the trowel and the roar of heavy rain. "Even the skies are crying for you, Moataz," Laham said. Then he, Mahmoud, and the gravedigger shoveled wet earth on top of the cement and smoothed it evenly across the surface. At that point, Laham remembers, Mahmoud Mughrabi praised the gravedigger for fitting his grave so precisely to the size of Moataz's body.

"Make mine longer, please," he told him. "I want to be able to rest."

Laham looked at him in surprise. "How can you talk like that?" he said.

Mahmoud just smiled.

That night the Mughrabi family gathered around the dining table for iftar -- the big evening meal that breaks the dawn-to-dusk Ramadan fast -- and over lamb, rice, and yogurt discussed the worsening violence in the West Bank. At ten o'clock on that cold and rainy night, Mahmoud and Ahmed Mughrabi left the house together, as they often did. This time they met another Deheishe resident named Jad Salem Attala, a bespectacled recent graduate of Bethlehem University, who had also been a frequent participant in the clashes at Rachel's Tomb. Mahmoud Mughrabi had a Kalashnikov rifle; Jad Attala carried a homemade bomb in a backpack. The three planned to lay the explosive on a road just outside Beit Jala, in Israeli-controlled territory. Israeli jeeps and armored vehicles passed along this road frequently on their way to a hilltop military base.

After midnight the three men drove to the top of Beit Jala and climbed over an earthen barricade that blocked the exit leading into the Israeli-occupied West Bank. At the start of the intifada Israeli military bulldozers had blocked many such roads to seal Palestinian-controlled towns and prevent militants from driving out. As the men laid the device in the road, an Israeli patrol opened fire, hitting Mahmoud Mughrabi in the legs. "Mahmoud started crawling back painfully through the rocks," Yusuf Mughrabi told me, basing his account on what Ahmed had reported to him. "Ahmed reached him, and he took the Kalashnikov from his brother. Immediately he wanted to start shooting at the soldiers, but then he had a vision of his mother standing in front of him, and he felt it would be too painful for her to see both of her sons killed at the same time." With Mahmoud unable to walk and the Israelis fast approaching, Ahmed and Jad Attala retreated across the earthen barricade and into the safety of Beit Jala, leaving Mahmoud to his fate.

At dawn the next morning the Israeli army turned over the body of Mahmoud Mughrabi to the District Coordination Office, an agency on the Beit Jala border that functions as a liaison between the Israeli military and the Palestinian National Security Force. He had bullet wounds in his head as well as his legs: Dr. Peter Qumri, director and chief surgeon of Beit Jala's al-Hussein Hospital, who examined Mahmoud's body later that day, told me that the evidence pointed to an execution. "There was lots of earth on his legs that shows he was dragged," Qumri says. "He was shot in his head from a very short distance." (The Israeli Defense Forces ignored several requests I made for their version of events.) Yusuf Mughrabi smiled as he stood over his son's corpse in the morgue, a Palestinian journalist who witnessed the scene told me. He touched his fingers softly to his lips and pressed them against Mahmoud's lips, as if sending him a good-bye kiss. Moments later, when his fourteen-year-old son Ali began to cry, Yusuf slapped him across his face. "Cut it out," he told his youngest son. "Your brother is a shaheed and you are crying?" Ahmed Mughrabi also came to say good-bye to his younger brother, betraying as little sentiment as his father. "Congratulations," he had told his mother upon learning of Mahmoud's death. "Your son has become a martyr." Few people will ever know whether Ahmed felt guilty about leaving his brother to face execution, but those acquainted with him said a change came over him that day. As he gazed intently at Mahmoud's corpse, he was perhaps already plotting the course of revenge that would transform him into one of Israel's deadliest enemies. "Bastard," the Palestinian reporter heard Ahmed Mughrabi say in front of his brother's body. "He made it before I did."

Copyright © 2003 by Joshua Hammer

Product Details

- Publisher: Free Press (June 3, 2004)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743256049

Raves and Reviews

Fareed Zakaria author of The Future of Freedom Joshua Hammer reports like a journalist and writes like a novelist. The result is a gripping book that tells the story of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through one town and a dozen people, whose lives come together in the climactic 39-day siege of Bethlehem. There have been many books written about the history, the politics, and the violence of the Middle East. This is a book about the people who live through it all.

Scott Anderson author of The Man Who Tried to Save the World Joshua Hammer has achieved something truly remarkable here: by focusing on a single seminal event in modern Arab-Israeli history -- the 2002 siege of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem -- and letting its participants tell their stories, he has cast a piercing light on the passions and furies that plague the Holy Land. Rather than another polemic on the Middle East troubles, A Season in Bethlehem reads like a thriller -- a particularly thoughtful and humane one.

Amy Wilentz author of Martyr's Crossing A Season in Bethlehem examines this fascinating, historic city in microcosm, and uses it to explain why the situation in the Middle East is so explosive. Hammer's detailed portraits of all the actors and his incredible ability to create atmosphere bring the whole place to life. His moment-by-moment narration of the siege of the Church of the Nativity is riveting. You can't believe Hammer was so near all this, observing firsthand the terrible tension, the dangerous standoff. A brave book.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): A Season in Bethlehem Trade Paperback 9780743256049(1.9 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Joshua Hammer Cordula Krämer(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit