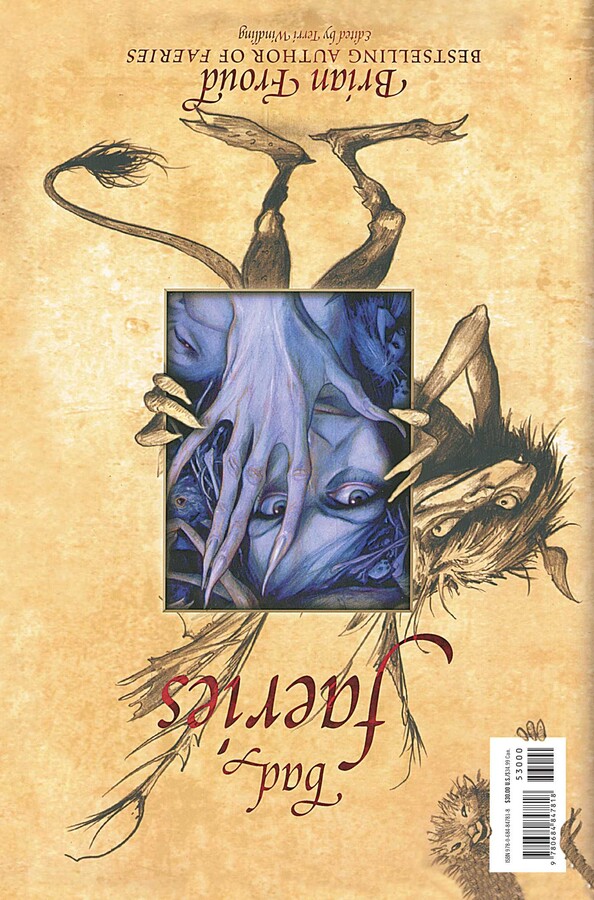

Good Faeries Bad Faeries

By Brian Froud

LIST PRICE $32.00

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

"Once upon a time, I thought faeries lived only in books, old folktales, and the past. That was before they burst upon my life as vibrant, luminous beings, permeating my art and my everyday existence, causing glorious havoc...."

In the long-awaited sequel to the international bestseller Faeries, artist Brian Froud rescues pixies, gnomes, and other faeries from the isolation of the nursery and the distance of history, bringing them into the present day with vitality and imagination. In this richly imagined new book, Brian reveals the secrets he has learned from the faeries -- what their noses and shoes look like, what mischief and what gentle assistance they can give, what their souls and their dreams are like.

As it turns out, faeries aren't all sweetness and light. In addition to such good faeries as Dream Weavers and Faery Godmothers, Brian introduces us to a host of less well behaved creatures -- traditional bad faeries like Morgana le Fay, but also the Soul Shrinker and the Gloominous Doom. The faery kingdom, we find, is as subject to good and evil as the human realm. Brilliantly documenting both the dark and the light, Good Faeries/Bad Faeries presents a world of enchantment and magic that deeply compels the imagination.

In the long-awaited sequel to the international bestseller Faeries, artist Brian Froud rescues pixies, gnomes, and other faeries from the isolation of the nursery and the distance of history, bringing them into the present day with vitality and imagination. In this richly imagined new book, Brian reveals the secrets he has learned from the faeries -- what their noses and shoes look like, what mischief and what gentle assistance they can give, what their souls and their dreams are like.

As it turns out, faeries aren't all sweetness and light. In addition to such good faeries as Dream Weavers and Faery Godmothers, Brian introduces us to a host of less well behaved creatures -- traditional bad faeries like Morgana le Fay, but also the Soul Shrinker and the Gloominous Doom. The faery kingdom, we find, is as subject to good and evil as the human realm. Brilliantly documenting both the dark and the light, Good Faeries/Bad Faeries presents a world of enchantment and magic that deeply compels the imagination.

Excerpt

Introduction from Bad Faeries

Although people nowadays tend to think of faeries as gentle little sprites, anyone who has encountered faeries knows they can be tricksy, capricious, even dangerous. Our ancestors certainly knew this. Folklore is filled with cautionary tales about the perils of faery encounters, and in centuries past there were many places where people did not dare to go a-hunting for fear of little men.

The idea that the world is full of spirit beings both bad and good is one we find in the oldest myths and tales from cultures the world over. In ancient Greece, the Neoplatonist Porphyry (c. 232-c. 305 A.D.) wrote that the air was inhabited by good and bad spirits with fluid bodies of no fixed shape, creatures who change their form at will. These were certainly faeries. Porphyry explained that the bad spirits were composed of turbulent malignity and created disruptions whenever humans failed to address them with respect. The Romans acknowledged the presence of faery spirits called the Lares, who, when venerated properly at the hearth (the heart) of the household, protected the home and family. The Lares were ruled over by their mother, Larunda, an earth goddess and faery queen. The Roman bogeymen were the Lemures, dark spirits of the night. They had all the traits of bad faeries and had to be placated by throwing black beans at them while turning one's head away.

In northern Europe, the maggots emerging from the dead body of the giant Ymir transmuted into light and dark elves -- light elves inhabiting the air, dark elves dwelling in the earth. Persian faeries, known as the peri, were creatures formed of the element of fire existing on a diet of perfume and other exquisite odors. The bad faeries of Persia, called the dev, were forever at war with the peri, whom they captured and locked away in iron cages hanging high in trees. Other faery creatures, both benevolent and malign, appear in tales from many far-flung lands: the laminak of Basque folklore, the grama-devata of India, the jinn of Arabia, the hsien of China, the yumboes of West Africa, the underhill people of the Cherokee...and numerous other spirits who have both plagued and aided humankind since the world began.

In the early seventeenth century, a certain Dr. Jackson held the view that good and bad faeries are simply two sides of the same coin: "Thus are the fayries from difference of events ascribed to them, divided into Good and Bad, when it is by one and the same malignant fiend that meddled in both, seeking sometimes to be feared, otherwiles to be loved." An English text from the sixteenth century states that "there be three kinds of fairies, the black, the white and the green, of which the black be the woorst" -- although in Shakespeare's The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), another group of faeries was added: "faeries black, grey, green and white," with little indication as to their nature.

In old Scotland, there was no doubt that there were only two groups of faeries: the Gude Fairies and the Wicked Wichts. In the former category was the Seelie Court (the good or blessed court), a host of faeries who were benefactors to humans, giving bread, seeds, and comfort to the needy. These faeries might give secret help in threshing, weaving, and household chores, and were generally kind -- but they were strict in their demands for appropriate reparation. The Unseelie Court, by contrast, were fearsome creatures, inflicting various harms and ills on man and beast alike. In The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (1911), the American folklorist W.Y. Evans Wentz asserted that the faery race had the power to destroy half the human race yet refrained from doing so out of ethical considerations. Lady Gregory (the Irish folklorist, playwright, and patron of W B. Yeats) held the faeries in rather less awe; she claimed they were merely capricious and mischievous, like unruly children.

In modern life, we are not free from the plagues and torments of bad faeries. They make their presence known to us through all manner of disruptions, from minor irritations to serious problems affecting health and well-being.

Among the minor faery mischief makers are ones we're all familiar with: the snagger, whose sharp claws attack women's stockings before they leave the house; the various spotters and stainers, who leave the grubby evidence of their manifestation on a freshly laundered blouse or tie, usually right before that important business meeting; the sneaker sneaker, who always waits until Monday morning, when the kids are late for the bus, to silently sneak away with a shoe. We've all had personal tongue tanglers, and sudden stark panics, and gloominous dooms, and moments when afterward we say: Good heavens, whatever possessed me? The faeries have possessed you, tangling your words, your thoughts, your feet, or your fate. These capricious creatures have been known as frairies, feriers, ferishers, fear-sidhe (faery men), and fearies -- a whole race of beings known to block potential and clarity of thought. They hide behind tiny irritations and lurk within our daily disasters. In more serious guise, they're the faery blights whose touch can cause depressions, addictions, compulsions, and moments of dark despair.

It is the nature of faeries to be unruly, chaotic, disruptive, subversive, confusing, ambivalent, paradoxical, and downright frustrating. Yet even these bad interferences serve an important function. They remind us of the value of connection, wholeness, and openness by holding a mirror up to us and showing us the opposite. Bad faeries, from the small sock stealers to the larger creatures of gloom and doom, are (like all faeries) expressions of nature and of our own deepest selves. They are manifestations of psychic blocks, distortions, and unresolved emotions; they give form and personality to negative forces and abstractions. They nip and prod us, asking for simple acknowledgment of their presence in our lives, insisting that we take notice of them -- the first step to healing or change.

It cannot be denied that sickness, madness, and even death have been reported in many old tales concerning encounters with the shadow side of Faeryland -- yet the same faeries have also been known to give gifts, guidance, and aid to the needy, and to heal mortals of illnesses both physical and psychological. I believe no faery is completely good or bad, but fluidly embodies both extremes. Any faery can be either one or the other in his or her equivocal relationship with us. They change with circumstance, with whim, and with motivations far beyond our human ken. Their actions and reactions generally work toward engaging us at deeper and deeper levels of consciousness -- insisting we be conscious of them, of ourselves, and of the world around us. They can become quite angry and disruptive if we're not awake and paying attention -- particularly if they feel they've not been properly acknowledged.

The bad faery in the story "Sleeping Beauty" is one example: she is angry because she has been neglected -- overlooked at the christening feast. Yet her wickedness initiates the events that lead to the princess's final transformation. Could this have been her intent all along, beyond the guise of wickedness? When dealing with the faeries it is wise to remember that things aren't always as they first appear. What seems to be bad behavior might have a deeper, underlying reason.

Despite our tendency to split the world into good and bad, right and wrong, light and dark, we must remember that in truth (and in the faery realms) such divisions are not always cleanly cut. Each contains a piece of the other, holding the world in tension and balance. And the shape-shifting denizens of Faery can appear wearing either face.

Copyright © 1998 by Brian Froud

Although people nowadays tend to think of faeries as gentle little sprites, anyone who has encountered faeries knows they can be tricksy, capricious, even dangerous. Our ancestors certainly knew this. Folklore is filled with cautionary tales about the perils of faery encounters, and in centuries past there were many places where people did not dare to go a-hunting for fear of little men.

The idea that the world is full of spirit beings both bad and good is one we find in the oldest myths and tales from cultures the world over. In ancient Greece, the Neoplatonist Porphyry (c. 232-c. 305 A.D.) wrote that the air was inhabited by good and bad spirits with fluid bodies of no fixed shape, creatures who change their form at will. These were certainly faeries. Porphyry explained that the bad spirits were composed of turbulent malignity and created disruptions whenever humans failed to address them with respect. The Romans acknowledged the presence of faery spirits called the Lares, who, when venerated properly at the hearth (the heart) of the household, protected the home and family. The Lares were ruled over by their mother, Larunda, an earth goddess and faery queen. The Roman bogeymen were the Lemures, dark spirits of the night. They had all the traits of bad faeries and had to be placated by throwing black beans at them while turning one's head away.

In northern Europe, the maggots emerging from the dead body of the giant Ymir transmuted into light and dark elves -- light elves inhabiting the air, dark elves dwelling in the earth. Persian faeries, known as the peri, were creatures formed of the element of fire existing on a diet of perfume and other exquisite odors. The bad faeries of Persia, called the dev, were forever at war with the peri, whom they captured and locked away in iron cages hanging high in trees. Other faery creatures, both benevolent and malign, appear in tales from many far-flung lands: the laminak of Basque folklore, the grama-devata of India, the jinn of Arabia, the hsien of China, the yumboes of West Africa, the underhill people of the Cherokee...and numerous other spirits who have both plagued and aided humankind since the world began.

In the early seventeenth century, a certain Dr. Jackson held the view that good and bad faeries are simply two sides of the same coin: "Thus are the fayries from difference of events ascribed to them, divided into Good and Bad, when it is by one and the same malignant fiend that meddled in both, seeking sometimes to be feared, otherwiles to be loved." An English text from the sixteenth century states that "there be three kinds of fairies, the black, the white and the green, of which the black be the woorst" -- although in Shakespeare's The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), another group of faeries was added: "faeries black, grey, green and white," with little indication as to their nature.

In old Scotland, there was no doubt that there were only two groups of faeries: the Gude Fairies and the Wicked Wichts. In the former category was the Seelie Court (the good or blessed court), a host of faeries who were benefactors to humans, giving bread, seeds, and comfort to the needy. These faeries might give secret help in threshing, weaving, and household chores, and were generally kind -- but they were strict in their demands for appropriate reparation. The Unseelie Court, by contrast, were fearsome creatures, inflicting various harms and ills on man and beast alike. In The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (1911), the American folklorist W.Y. Evans Wentz asserted that the faery race had the power to destroy half the human race yet refrained from doing so out of ethical considerations. Lady Gregory (the Irish folklorist, playwright, and patron of W B. Yeats) held the faeries in rather less awe; she claimed they were merely capricious and mischievous, like unruly children.

In modern life, we are not free from the plagues and torments of bad faeries. They make their presence known to us through all manner of disruptions, from minor irritations to serious problems affecting health and well-being.

Among the minor faery mischief makers are ones we're all familiar with: the snagger, whose sharp claws attack women's stockings before they leave the house; the various spotters and stainers, who leave the grubby evidence of their manifestation on a freshly laundered blouse or tie, usually right before that important business meeting; the sneaker sneaker, who always waits until Monday morning, when the kids are late for the bus, to silently sneak away with a shoe. We've all had personal tongue tanglers, and sudden stark panics, and gloominous dooms, and moments when afterward we say: Good heavens, whatever possessed me? The faeries have possessed you, tangling your words, your thoughts, your feet, or your fate. These capricious creatures have been known as frairies, feriers, ferishers, fear-sidhe (faery men), and fearies -- a whole race of beings known to block potential and clarity of thought. They hide behind tiny irritations and lurk within our daily disasters. In more serious guise, they're the faery blights whose touch can cause depressions, addictions, compulsions, and moments of dark despair.

It is the nature of faeries to be unruly, chaotic, disruptive, subversive, confusing, ambivalent, paradoxical, and downright frustrating. Yet even these bad interferences serve an important function. They remind us of the value of connection, wholeness, and openness by holding a mirror up to us and showing us the opposite. Bad faeries, from the small sock stealers to the larger creatures of gloom and doom, are (like all faeries) expressions of nature and of our own deepest selves. They are manifestations of psychic blocks, distortions, and unresolved emotions; they give form and personality to negative forces and abstractions. They nip and prod us, asking for simple acknowledgment of their presence in our lives, insisting that we take notice of them -- the first step to healing or change.

It cannot be denied that sickness, madness, and even death have been reported in many old tales concerning encounters with the shadow side of Faeryland -- yet the same faeries have also been known to give gifts, guidance, and aid to the needy, and to heal mortals of illnesses both physical and psychological. I believe no faery is completely good or bad, but fluidly embodies both extremes. Any faery can be either one or the other in his or her equivocal relationship with us. They change with circumstance, with whim, and with motivations far beyond our human ken. Their actions and reactions generally work toward engaging us at deeper and deeper levels of consciousness -- insisting we be conscious of them, of ourselves, and of the world around us. They can become quite angry and disruptive if we're not awake and paying attention -- particularly if they feel they've not been properly acknowledged.

The bad faery in the story "Sleeping Beauty" is one example: she is angry because she has been neglected -- overlooked at the christening feast. Yet her wickedness initiates the events that lead to the princess's final transformation. Could this have been her intent all along, beyond the guise of wickedness? When dealing with the faeries it is wise to remember that things aren't always as they first appear. What seems to be bad behavior might have a deeper, underlying reason.

Despite our tendency to split the world into good and bad, right and wrong, light and dark, we must remember that in truth (and in the faery realms) such divisions are not always cleanly cut. Each contains a piece of the other, holding the world in tension and balance. And the shape-shifting denizens of Faery can appear wearing either face.

Copyright © 1998 by Brian Froud

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (October 15, 1998)

- Length: 192 pages

- ISBN13: 9780684847818

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Good Faeries Bad Faeries Hardcover 9780684847818(0.5 MB)