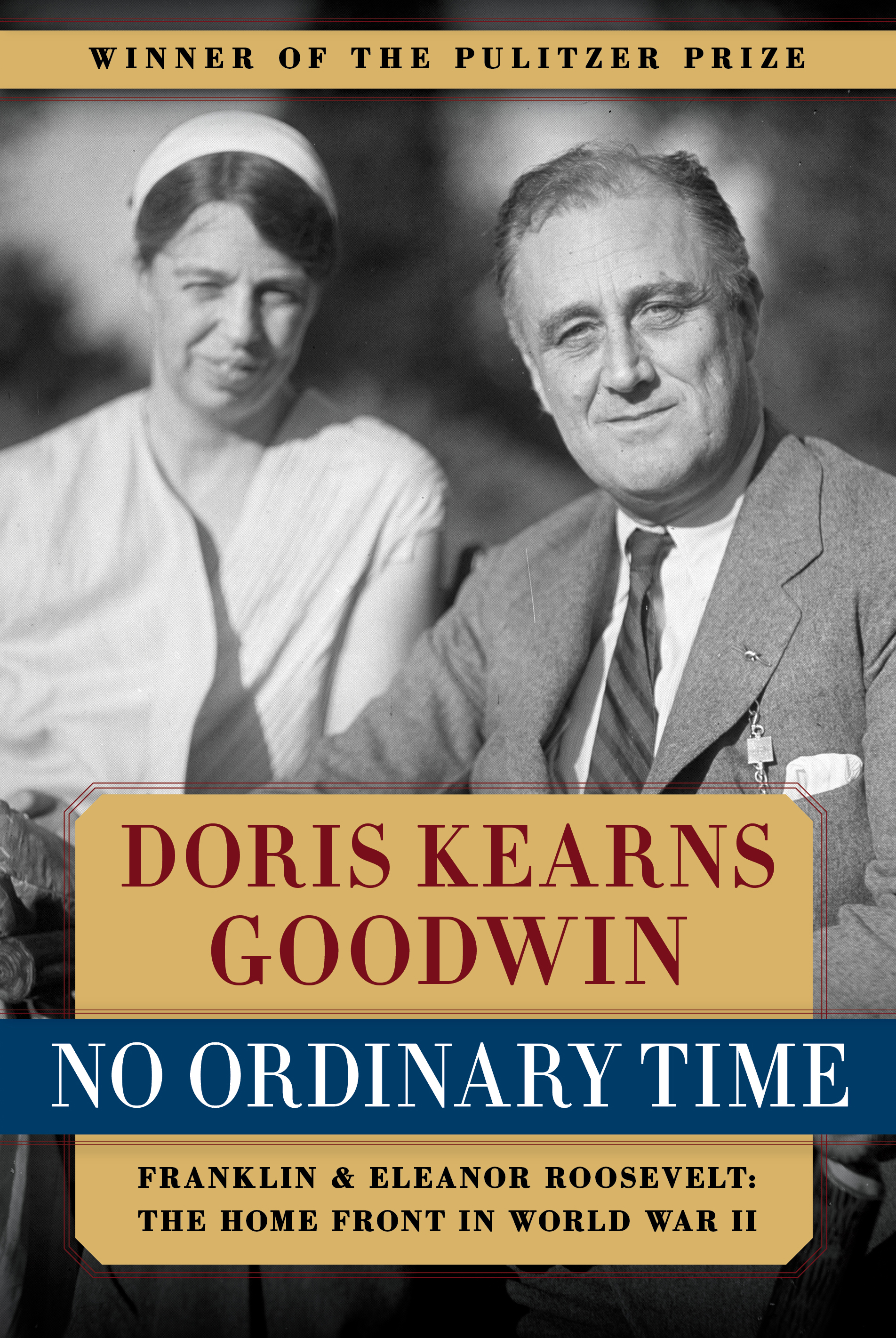

No Ordinary Time

Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II

LIST PRICE $24.00

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

With an extraordinary collection of details, Goodwin masterfully weaves together a striking number of story lines—Eleanor and Franklin’s marriage and remarkable partnership, Eleanor’s life as First Lady, and FDR’s White House and its impact on America as well as on a world at war. Goodwin effectively melds these details and stories into an unforgettable and intimate portrait of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt and of the time during which a new, modern America was born.

Excerpt

"THE DECISIVE HOUR HAS COME"

On nights filled with tension and concern, Franklin Roosevelt performed a ritual that helped him to fall asleep. He would close his eyes and imagine himself at Hyde Park as a boy, standing with his sled in the snow atop the steep hill that stretched from the south porch of his home to the wooded bluffs of the Hudson River far below. As he accelerated down the hill, he maneuvered each familiar curve with perfect skill until he reached the bottom, whereupon, pulling his sled behind him, he started slowly back up until he reached the top, where he would once more begin his descent. Again and again he replayed this remembered scene in his mind, obliterating his awareness of the shrunken legs inert beneath the sheets, undoing the knowledge that he would never climb a hill or even walk on his own power again. Thus liberating himself from his paralysis through an act of imaginative will, the president of the United States would fall asleep.

The evening of May 9, 1940, was one of these nights. At 11 p.m., as Roosevelt sat in his comfortable study on the second floor of the White House, the long-apprehended phone call had come. Resting against the high back of his favorite red leather chair, a precise reproduction of one Thomas Jefferson had designed for work, the president listened as his ambassador to Belgium, John Cudahy, told him that Hitler's armies were simultaneously attacking Holland, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France. The period of relative calm -- the "phony war" that had settled over Europe since the German attack on Poland in September of 1939 -- was over.

For days, rumors of a planned Nazi invasion had spread through the capitals of Western Europe. Now, listening to Ambassador Cudahy's frantic report that German planes were in the air over the Low Countries and France, Roosevelt knew that the all-out war he feared had finally begun. In a single night, the tacit agreement that, for eight months, had kept the belligerents from attacking each other's territory had been shattered.

As he summoned his military aide and appointments secretary, General Edwin "Pa" Watson, on this spring evening of the last year of his second term, Franklin Roosevelt looked younger than his fifty-eight years. Though his hair was threaded with gray, the skin on his handsome face was clear, and the blue eyes, beneath his pince-nez glasses, were those of a man at the peak of his vitality. His chest was so broad, his neck so thick, that when seated he appeared larger than he was. Only when he was moved from his chair would the eye be drawn to the withered legs, paralyzed by polio almost two decades earlier.

At 12:40 a.m., the president's press secretary, Stephen Early, arrived to monitor incoming messages. Bombs had begun to fall on Brussels, Amsterdam, and Rotterdam, killing hundreds of civilians and destroying thousands of homes. In dozens of old European neighborhoods, fires illuminated the night sky. Stunned Belgians stood in their nightclothes in the streets of Brussels, watching bursts of anti-aircraft fire as military cars and motorcycles dashed through the streets. A thirteen-year-old schoolboy, Guy de Liederkirche, was Brussels' first child to die. His body would later be carried to his school for a memorial service with his classmates. On every radio station throughout Belgium, broadcasts summoned all soldiers to join their units at once.

In Amsterdam the roads leading out of the city were crowded with people and automobiles as residents fled in fear of the bombing. Bombs were also falling at Dunkirk, Calais, and Metz in France, and at Chilham, near Canterbury, in England. The initial reports were confusing -- border clashes had begun, parachute troops were being dropped to seize Dutch and Belgian airports, the government of Luxembourg had already fled to France, and there was some reason to believe the Germans were also landing troops by sea.

After speaking again to Ambassador Cudahy and scanning the incoming news reports, Roosevelt called his secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., and ordered him to freeze all assets held by Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg before the market opened in the morning, to keep any resources of the invaded countries from falling into German hands.

The official German explanation for the sweeping invasion of the neutral lowlands was given by Germany's foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Germany, he claimed, had received "proof" that the Allies were engineering an imminent attack through the Low Countries into the German Ruhr district. In a belligerent tone, von Ribbentrop said the time had come for settling the final account with the French and British leaders. Just before midnight, Adolf Hitler, having boarded a special train to the front, had issued the fateful order to his troops: "The decisive hour has come for the fight today decides the fate of the German nation for the next 1000 years."

There was little that could be done that night -- phone calls to Paris and Brussels could rarely be completed, and the Hague wire was barely working -- but, as one State Department official said, "in times of crisis the key men should be at hand and the public should know it." Finally, at 2:40 a.m., Roosevelt decided to go to bed. After shifting his body to his armless wheel chair, he rolled through a door near his desk into his bedroom.

As usual when the president's day came to an end, he called for his valet, Irvin McDuffie, to lift him into his bed. McDuffie, a Southern Negro, born the same year as his boss, had been a barber by trade when Roosevelt met him in Warm Springs, Georgia, in 1927. Roosevelt quickly developed a liking for the talkative man and offered him the job of valet. Now he and his wife lived in a room on the third floor of the White House. In recent months, McDuffie's hard drinking had become a problem: on several occasions Eleanor had found him so drunk that "he couldn't help Franklin to bed." Fearing that her husband might be abandoned at a bad time, Eleanor urged him to fire McDuffie, but the president was unable to bring himself to let his old friend go, even though he shared Eleanor's fear.

McDuffie was at his post in the early hours of May 10 when the president called for help. He lifted the president from his wheelchair onto the narrow bed, reminiscent of the kind used in a boy's boarding school, straightened his legs to their full length, and then undressed him and put on his pajamas. Beside the bed was a white-painted table; on its top, a jumble of pencils, notepaper, a glass of water, a package of cigarettes, a couple of phones, a bottle of nose drops. On the floor beside the table stood a small basket -- the Eleanor basket -- in which the first lady regularly left memoranda, communications, and reports for the president to read -- a sort of private post office between husband and wife. In the corner sat an old-fashioned rocking chair, and next to it a heavy wardrobe filled with the president's clothes. On the marble mantelpiece above the fireplace was an assortment of family photos and a collection of miniature pigs. "Like every room in any Roosevelt house," historian Arthur Schlesinger has written, "the presidential bedroom was hopelessly Victorian -- old-fashioned and indiscriminate in its furnishings, cluttered in its decor, ugly and comfortable."

Outside Roosevelt's door, which he refused to lock at night as previous presidents had done, Secret Service men patrolled the corridor, alerting the guardroom to the slightest hint of movement. The refusal to lock his door was related to the president's dread of fire, which surpassed his fear of assassination or of anything else. The fear seems to have been rooted in his childhood, when, as a small boy, he had seen his young aunt, Laura, race down the stairs, screaming, her body and clothes aflame from an accident with an alcohol lamp. Her life was ended at nineteen. The fear grew when he became a paraplegic, to the point where, for hours at a time, he would practice dropping from his bed or chair to the floor and then crawling to the door so that he could escape from a fire on his own. "We assured him he would never be alone," his eldest son, Jimmy, recalled, "but he could not be sure, and furthermore found the idea depressing that he could not be left alone, as if he were an infant."

Roosevelt's nightly rituals tell us something about his deepest feelings -- the desire for freedom, the quest for movement, and the significance, despite all his attempts to downplay it, of the paralysis in his life. In 1940, Roosevelt had been president of the United States for seven years, but he had been paralyzed from the waist down for nearly three times that long. Before he was stricken at thirty-nine, Roosevelt was a man who flourished on activity. He had served in the New York legislature for two years, been assistant secretary of the navy for seven years, and his party's candidate for vice-president in 1920. He loved to swim and to sail, to play tennis and golf; to run in the woods and ride horseback in the fields. To his daughter, Anna, he was always "very active physically," "a wonderful playmate who took long walks with you, sailed with you, could out-jump you and do a lot of things," while Jimmy saw him quite simply as "the handsomest, strongest, most glamorous, vigorous physical father in the world."

All that vigor and athleticism ended in August 1921 at Campobello, his family's summer home in New Brunswick, Canada, when he returned home from swimming in the pond with his children and felt too tired even to remove his wet bathing suit. The morning after his swim, his temperature was 102 degrees and he had trouble moving his left leg. By afternoon, the power to move his right leg was also gone, and soon he was paralyzed from the waist down. The paralysis had set in so swiftly that no one understood at first that it was polio. But once the diagnosis was made, the battle was joined. For years he fought to walk on his own power, practicing for hours at a time, drenched with sweat, as he tried unsuccessfully to move one leg in front of the other without the aid of a pair of crutches or a helping hand. That consuming and futile effort had to be abandoned once he became governor of New York in 1929 and then president in 1933. He was permanently crippled.

Yet the paralysis that crippled his body expanded his mind and his sensibilities. After what Eleanor called his "trial by fire," he seemed less arrogant, less smug, less superficial, more focused, more complex, more interesting. He returned from his ordeal with greater powers of concentration and greater self-knowledge. "There had been a plowing up of his nature," Labor Secretary Frances Perkins observed. "The man emerged completely warmhearted, with new humility of spirit and a firmer understanding of profound philosophical concepts."

He had always taken great pleasure in people. But now they became what one historian has called "his vital links with life." Far more intensely than before, he reached out to know them, to understand them, to pick up their emotions, to put himself into their shoes. No longer belonging to his old world in the same way, he came to empathize with the poor and underprivileged, with people to whom fate had dealt a difficult hand. Once, after a lecture in Akron, Ohio, Eleanor was asked how her husband's illness had affected him. "Anyone who has gone through great suffering," she said, "is bound to have a greater sympathy and understanding of the problems of mankind."

Through his presidency, the mere act of standing up with his heavy metal leg-braces locked into place was an ordeal. The journalist Eliot Janeway remembers being behind Roosevelt once when he was in his chair in the Oval Office. "He was smiling as he talked. His face and hand muscles were totally relaxed. But then, when he had to stand up, his jaws went absolutely rigid. The effort of getting what was left of his body up was so great his face changed dramatically. It was as if he braced his body for a bullet."

Little wonder, then, that, in falling asleep at night, Roosevelt took comfort in the thought of physical freedom.

The morning sun of Washington's belated spring was streaming through the president's windows on May 10, 1940. Despite the tumult of the night before, which had kept him up until nearly 3 a.m., he awoke at his usual hour of eight o'clock. Pivoting to the edge of the bed, he pressed the button for his valet, who helped him into the bathroom. Then, as he had done every morning for the past seven years, he threw his old blue cape over his pajamas and started his day with breakfast in bed -- orange juice, eggs, coffee, and buttered toast -- and the morning, papers: The New York Times and the Herald Tribune, the Baltimore Sun, the Washington Post and the Washington Herald.

Headlines recounted the grim events he had heard at 11 p.m. the evening before. From Paris, Ambassador William Bullitt confirmed that the Germans had launched violent attacks on a half-dozen French military bases. Bombs had also fallen on the main railway connections between Paris and the border in an attempt to stop troop movements.

Before finishing the morning papers, the president held a meeting with Steve Early and "Pa" Watson, to review his crowded schedule. He instructed them to convene an emergency meeting at ten-thirty with the chiefs of the army and the navy, the secretaries of state and Treasury, and the attorney general. In addition, Roosevelt was scheduled to meet the press in the morning and the Cabinet in the afternoon, as he had done every Friday morning and afternoon for seven years. Later that night, he was supposed to deliver a keynote address at the Pan American Scientific Congress. After asking Early to delay the press conference an hour and to have the State Department draft a new speech, Roosevelt called his valet to help him dress.

While Franklin Roosevelt was being dressed in his bedroom, Eleanor was in New York, having spent the past few days in the apartment she kept in Greenwich Village, in a small house owned by her friends Esther Lape and Elizabeth Read. The Village apartment on East 11th Street, five blocks north of Washington Square, provided Eleanor with a welcome escape from the demands of the White House, a secret refuge whenever her crowded calendar brought her to New York. For decades, the Village, with its winding streets, modest brick houses, bookshops, tearooms, little theaters, and cheap rents, had been home to political, artistic, and literary rebels, giving it a colorful Old World character.

The object of Eleanor's visit to the city -- her second in ten days -- was a meeting that day at the Choate School in Connecticut, where she was scheduled to speak with teachers and students. Along the way, she had sandwiched in a banquet for the National League of Women Voters, a meeting for the fund for Polish relief, a visit to her mother-in-law, Sara Delano Roosevelt, a radio broadcast, lunch with her friend the young student activist Joe Lash, and dinner with Democratic leader Edward Flynn and his wife.

The week before, at the Astor Hotel, Eleanor had been honored by The Nation magazine for her work in behalf of civil rights and poverty. More than a thousand people had filled the tables and the balcony of the cavernous ballroom to watch her receive a bronze plaque for "distinguished service in the cause of American social progress." Among the many speakers that night, Stuart Chase lauded the first lady's concentrated focus on the problems at home. "I suppose she worries about Europe like the rest of us," he began, "but she does not allow this worry to divert her attention from the homefront. She goes around America, looking at America, thinking about America...helping day and night with the problems of America." For, he concluded, "the New Deal is supposed to be fighting a war, too, a war against depression."

"What is an institution?" author John Gunther had asked when his turn to speak came. "An institution," he asserted, is "something that had fixity, permanence, and importance...something that people like to depend on, something benevolent as a rule, something we like." And by that definition, he concluded, the woman being honored that night was as great an institution as her husband, who was already being talked about for an unprecedented third term. Echoing Gunther's sentiments, NAACP head Walter White turned to Mrs. Roosevelt and said: "My dear, I don't care if the President runs for the third or fourth term as long as he lets you run the bases, keep the score and win the game."

For her part, Eleanor was slightly embarrassed by all the fuss. "It never seems quite real to me to sit at a table and have people whom I have always looked upon with respect...explain why they are granting me an honor," she wrote in her column describing the evening. "Somehow I always feel they ought to be talking about someone else." Yet, as she stood to speak that night at the Astor ballroom, rising nearly six feet, her wavy brown hair slightly touched by gray, her wide mouth marred by large buck teeth, her brilliant blue eyes offset by an unfortunate chin, she dominated the room as no one before her had done. "I will do my best to do what is right," she began, forcing her high voice to a lower range, "not with a sense of my own adequacy but with the feeling that the country must go on, that we must keep democracy and must make it mean a reality to more people....We should constantly be reminded of what we owe in return for what we have."

It was this tireless commitment to democracy's unfinished agenda that led Americans in a Gallup poll taken that spring to rate Mrs. Roosevelt even higher than her husband, with 67 percent of those interviewed well disposed toward her activities. "Mrs. Roosevelt's incessant goings and comings," the survey suggested, "have been accepted as a rather welcome part of the national life. Women especially feel this way. But even men betray relatively small masculine impatience with the work and opinions of a very articulate lady....The rich, who generally disapprove of Mrs. Roosevelt's husband, seem just as friendly toward her as the poor....Even among those extremely anti-Roosevelt citizens who would regard a third term as a national disaster there is a generous minority...who want Mrs. Roosevelt to remain in the public eye."

The path to this position of independent power and respect had not been easy. Eleanor's distinguished career had been forged from a painful discovery when she was thirty-four. After a period of suspicion, she realized that her husband, who was then assistant secretary of the navy, had fallen in love with another woman, Lucy Page Mercer.

Tall, beautiful, and well bred, with a low throaty voice and an incomparably winning smile, Lucy Mercer was working as Eleanor's social secretary when the love affair began. For months, perhaps even years, Franklin kept his romance a secret from Eleanor. Her shattering discovery took place in September 1918. Franklin had just returned from a visit to the European front. Unpacking his suitcase, she discovered a packet of love letters from Lucy. At this moment, Eleanor later admitted, "the bottom dropped out of my own particular world & I faced myself, my surroundings, my world, honestly for the first time."

Eleanor told her husband that she would grant him a divorce. But this was not what he wanted, or at least not what he was able to put himself through, particularly when his mother, Sara, was said to have threatened him with disinheritance if he left his marriage. If her son insisted on leaving his wife and five children for another woman, visiting scandal upon the Roosevelt name, she could not stop him. But he should know that she would not give him another dollar and he could no longer expect to inherit the family estate at Hyde Park. Franklin's trusted political adviser, Louis Howe, weighed in as well, warning Franklin that divorce would bring his political career to an abrupt end. There was also the problem of Lucy's Catholicism, which would prevent her from marrying a divorced man.

Franklin promised never to see Lucy again and agreed, so the Roosevelt children suggest, to Eleanor's demand for separate bedrooms, bringing their marital relations to an end. Eleanor would later admit to her daughter, Anna, that sex was "an ordeal to be borne." Something in her childhood had locked her up, she said, making her fear the loss of control that comes with abandoning oneself to one's passions, giving her "an exaggerated idea of the necessity of keeping all one's desires under complete subjugation." Now, supposedly, she was free of her "ordeal."

The marriage resumed. But for Eleanor, a path had opened, a possibility of standing apart from Franklin. No longer did she need to define herself solely in terms of his wants and his needs. Before the crisis, though marriage had never fulfilled her prodigious energies, she had no way of breaking through the habits and expectations of a proper young woman's role. To explore her independent needs, to journey outside her home for happiness, was perceived as dangerous and wrong.

With the discovery of the affair, however, she was free to define a new and different partnership with her husband, free to seek new avenues of fulfillment. It was a gradual process, a gradual casting away, a gradual gaining of confidence -- and it was by no means complete -- but the fifty-six-year-old woman who was being feted in New York was a different person from the shy, betrayed wife of 1918.

Above the president's bedroom, in a snug third-floor suite, his personal secretary, Marguerite "Missy" LeHand, was already dressed, though she, too, had stayed up late the night before.

A tall, handsome woman of forty-one with large blue eyes and prematurely gray, once luxuriant black hair fastened by hairpins to the nape of her neck, Missy was in love with her boss and regarded herself as his other wife. Nor was she alone in her imaginings. "There's no doubt," White House aide Raymond Moley said, "that Missy was as close to being a wife as he ever had -- or could have." White House maid Lillian Parks agreed. "When Missy gave an order, we responded as if it had come from the First Lady. We knew that FDR would always back up Missy."

Missy had come a long way from the working-class neighborhood in Somerville, Massachusetts, where she had grown up. Her father was an alcoholic who lived apart from the family. Her mother, with five children to raise, took in a revolving group of Harvard students as tenants. Yet, even when she was young, Missy's childhood friend Barbara Curtis recalled, "she had a certain class to her. I remember one time watching her go around the corner -- our houses weren't too far apart -- and my mother looked out the window and called my attention to her. She said, 'she certainly looks smart.' She had a dark suit on to go to high school. She stood out for having a better appearance and being smarter than most."

After secretarial school, Missy had gone to New York, where she became involved in Roosevelt's vice-presidential campaign in 1920. Impressed by Missy's efficiency, Eleanor asked her to come to Hyde Park after the election to help Franklin clean up his correspondence. From the start, Missy proved herself indispensable. When asked later to explain her astonishing secretarial skill, she said simply, "The first thing for a private secretary to do is to study her employer. After I went to work for Mr. Roosevelt, for months I read carefully all the letters he dictated....I learned what letters he wanted to see and which ones it was not necessary to show him....I came to know exactly how Mr. Roosevelt would answer some of his letters, how he would couch his thoughts. When he discovered that I had learned these things it took a load off his shoulders, for instead of having to dictate the answers to many letters he could just say yes or no and I knew what to say and how to say it."

A year later, when Franklin contracted polio, Missy's duties expanded. Both Franklin and Eleanor understood that it was critical for Franklin to keep active in politics even as he struggled unsuccessfully day after day, month after month, to walk again. To that end, Eleanor adhered to a rigorous daily schedule as the stand-in for her husband, journeying from one political meeting to the next to ensure that the Roosevelt name was not forgotten. With Eleanor busily occupied away from home, Missy did all the chores a housewife might do, writing Franklin's personal checks, paying the monthly bills, giving the children their allowances, supervising the menus, sending the rugs and draperies for cleaning.

When Roosevelt was elected governor in 1928, Missy moved with the Roosevelt family to Albany, occupying a large bedroom suite on the second floor of the Governor's Mansion. "Albany was the hardest work I ever did," she said, recalling the huge load she carried for the activist governor without the help of the three assistants she would later enjoy in the White House. By the time Roosevelt was president, she had become totally absorbed in his life -- learning his favorite games, sharing his hobbies, reading the same books, even adopting his characteristic accent and patterns of speech. Whereas Eleanor was so opposed to gambling that she refused to play poker with Franklin's friends if even the smallest amount of money changed hands, Missy became an avid player, challenging Roosevelt at every turn, always ready to raise the ante. Whereas Eleanor never evinced any interest in her husband's treasured stamp collection, Missy was an enthusiastic partner, spending hours by his side as he organized and reorganized his stamps into one or another of his thick leather books. "In terms of companionship," Eliot Janeway observed, "Missy was the real wife. She understood his nature perfectly, as they would say in a nineteenth-century novel."

At 10:30 a.m., May 10, 1940, pushed along in his wheelchair by Mr. Crim, the usher on duty, and accompanied by his usual detail of Secret Service men, the president headed for the Oval Office. A bell announced his arrival to the small crowd already assembled in the Cabinet Room -- Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, Navy Chief Admiral Harold Stark, Attorney General Robert Jackson, Secretary of Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and Undersecretary Sumner Welles. But first, as he did every day, the president poked his head into Missy's office, giving her a wave and a smile which, Missy told a friend, was all she needed to replenish the energies lost from too little sleep.

Of all the men assembled in the big white-walled Cabinet Room that morning, General George Catlett Marshall possessed the clearest awareness of how woefully unprepared America was to fight a major war against Nazi Germany. The fifty-nine-year-old Marshall, chief of operations of the First Army in World War I, had been elevated to the position of army chief of staff the previous year. The story is told of a meeting in the president's office not long before the appointment during which the president outlined a pet proposal. Everyone nodded in approval except Marshall. "Don't you think so, George?" the president asked. Marshall replied: "I am sorry, Mr. President, but I don't agree with that at all." The president looked stunned, the conference was stopped, and Marshall's friends predicted that his tour of duty would soon come to an end. A few months later, reaching thirty-four names down the list of senior generals, the president asked the straight-speaking Marshall to be chief of staff of the U.S. Army.

The army Marshall headed, however, was scarcely worthy of the name, having languished in skeletal form since World War I, starved for funds and manpower by an administration focused on coping with the Great Depression and an isolationist Congress. Determined never again to be trapped by the corruptions of the Old World, the isolationists insisted that the United States was protected from harm by its oceans and could best lead by sustaining democracy at home. Responding to the overwhelming strength of isolationist sentiment in the country at large, the Congress had passed a series of Neutrality Acts in the mid-1930s banning the shipment of arms and munitions to all belligerents, prohibiting the extension of credits and loans, and forbidding the arming of merchant ships.

Roosevelt had tried on occasion to shift the prevailing opinion. In 1937, he had delivered a major speech in Chicago calling for a "quarantine" of aggressor nations. The speech was hailed by interventionists committed to collective security, but when the press evinced shock at what they termed a radical shift in foreign policy and isolationist congressmen threatened impeachment, Roosevelt had pulled back. "It's a terrible thing," he told his aide Sam Rosenman, "to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead -- and find no one there." He had resolved at that point to move one step at a time, to nurse the country along to a more sophisticated view of the world, to keep from getting too far ahead of the electorate, as Woodrow Wilson had done. The task was not easy. Even the outbreak of war in September had not led to a significant expansion of the army, since the president's first priority was to revise the Neutrality Laws so that he could sell weapons to the Allies. Fearing that larger appropriations for the ground forces would rouse the isolationists and kill his chances to reform neutrality policy, the president had turned a deaf ear to the army's appeals for expansion.

As a result, in 1940, the U.S. Army stood only eighteenth in the world, trailing not only Germany, France, Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan, and China but also Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. With the fall of Holland, the United States would rise to seventeenth! And, in contrast to Germany, where after years of compulsory military training nearly 10 percent of the population (6.8 million) were trained and ready for war, less than.5 percent of the American population (504,000) were on active duty or in the trained reserves. The offensive Germany had launched the morning of May 10 along the Western front was supported by 136 divisions; the United States could, if necessary, muster merely five fully equipped divisions.

In the spring of 1940, the United States possessed almost no munitions industry at all. So strong had been the recoil from war after 1918 that both the government and the private sector had backed away from making weapons. The result was that, while the United States led the world in the mass production of automobiles, washing machines, and other household appliances, the techniques of producing weapons of war had badly atrophied.

All through the winter and spring, Marshall had been trying to get Secretary of War Henry Woodring to understand the dire nature of this unpreparedness. But the former governor of Kansas was an isolationist who refused to contemplate even the possibility, of American involvement in the European war. Woodring had been named assistant secretary of war in 1933 and then promoted to the top job three years later, when the price of corn and the high unemployment rate worried Washington far more than foreign affairs. As the European situation heated up, Roosevelt recognized that Woodring was the wrong man to head the War Department. But, try as he might, he could not bring himself to fire his secretary of war -- or anyone else, for that matter.

Roosevelt's inability to get rid of anybody, even the hopelessly incompetent, was a chief source of the disorderliness of his administration, of his double-dealing and his tendency to procrastinate. "His real weakness," Eleanor Roosevelt observed, "was that -- it came out of the strength really, or out of a quality -- he had great sympathy for people and great understanding, and he couldn't bear to be disagreeable to someone he liked...and he just couldn't bring himself to really do the unkind thing that had to be done unless he got angry."

Earlier that spring, on at least two occasions, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes had brought up the Woodring problem with Roosevelt, suggesting an appointment as ambassador to Ireland as a face-saving gesture. The president did not think this would satisfy Woodring. "If I were you, Mr. President," Ickes replied, "I would send for Harry Woodring and I would say to him, 'Harry, it is either Dublin, Ireland for you or Topeka, Kansas.' The President looked at me somewhat abashed. Reading his mind, I said, 'You can't do that sort of thing, can you, Mr. President?' 'No, Harold, I can't,' he replied."

The confusion multiplied when Roosevelt selected a staunch interventionist, Louis Johnson, the former national commander of the American Legion, as assistant secretary of war. Outspoken, bold, and ambitious, Johnson fought openly with Woodring, bringing relations to the sorry point where neither man spoke to the other. Paralyzed and frustrated, General Marshall found it incomprehensible that Roosevelt had allowed such a mess to develop simply because he disliked firing anyone. Years earlier, when Marshall had been told by his aide that a friend whom he had ordered overseas had said he could not leave because his wife was away and his furniture was not packed, Marshall had called the man himself. The friend explained that he was sorry. "I'm sorry, too," Marshall replied, "but you will be retired tomorrow."

Marshall failed to understand that there was a method behind the president's disorderly style. Though divided authority and built-in competition created insecurity and confusion within the administration, it gave Roosevelt the benefit of conflicting opinions. "I think he knew exactly what he was doing all the time," administrative assistant James Rowe observed. "He liked conflict, and he was a believer in resolving problems through conflict." With different administrators telling him different things, he got a better feel for what his problems were.

Their attitude toward subordinates was not the only point of dissimilarity between Roosevelt and Marshall. Roosevelt loved to laugh and play, closing the space between people by familiarity, calling everyone, even Winston Churchill, by his first name. In contrast, Marshall was rarely seen to smile or laugh on the job and was never familiar with anyone. "I never heard him call anyone by his first name," Robert Cutler recalled. "He would use the rank or the last name or both: 'Colonel' or 'Colonel Cutler.' Only occasionally in wartime did he use the last name alone.... It was a reward for something he thought well done."

As army chief of staff, Marshall remained wary of Roosevelt's relaxed style. "Informal conversation with the President could get you into trouble," Marshall later wrote. "He would talk over something informally at the dinner table and you had trouble disagreeing without embarrassment. So I never went. I was in Hyde Park for the first time at his funeral."

As the officials sat in the Cabinet Room, at the great mahogany table under the stern, pinch-lipped stare of Woodrow Wilson, whose portrait hung above the fireplace, their primary reason for gathering together was to share the incoming information from Europe and to plan the American response. Ambassador John Cudahy in Brussels wired that he had almost been knocked down by the force of a bomb which fell three hundred feet from the embassy. From London, Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy reported that the British had called off their Whitsun holiday, the long weekend on which Londoners traditionally acquired the tan that had to last until their August vacation -- "tangible evidence," Kennedy concluded, "that the situation is serious."

Plans were set in motion for the army and navy to submit new estimates to the White House of what they would need to accomplish the seemingly insurmountable task of catching up with Germany's modern war machine. For, as Marshall had recently explained to the Congress, Germany was in a unique position. "After the World War practically everything was taken away from Germany in the way of materiel. So when Germany rearmed, it was necessary to produce a complete set of materiel for all the troops. As a result, Germany has an Army equipped throughout with the most modern weapons that could be turned out and that is a situation that has never occurred before in the history of the world."

While the president was conducting his meeting in the Cabinet Room, the men and women of the press were standing around in small groups, talking and smoking behind a red cord in a large anteroom, waiting for the signal that the press conference in the Oval Office was about to begin. The reporters had also been up late the night before, so "some were a little drawn eyed," the Tribune's Mark Sullivan observed. "We grouped about talking of -- do I need to say? I felt that...for many a day and month and year there will be talk about the effect of today's events upon the United States. We shall talk it and write it and live it, and our children's children, too."

The meeting concluded, the president returned to his desk, the red cord was withdrawn, and the reporters began filing in. In the front row, by tradition, stood the men representing the wire services: Douglas Cornell of Associated Press, Merriman Smith of United Press, and George Durno of the International News Service. Directly behind them stood the representatives of the New York and Washington papers. "Glancing around the room," a contemporary wrote, "one sees white-haired Mark Sullivan; dark Raymond Clapper; tall Ernest Lindley...and husky Paul Mallon." Farther back were the veterans of the out-of-town newspapers, the radio commentators, and the magazine men, led by Time's Felix Belair. And then the women reporters in fiat heels, among them Doris Fleeson of the New York Daily News and May Craig, representing several Maine newspapers.

Seated at his desk with his back to the windows, Roosevelt faced the crowd that was now spilling into the Oval Office for his largest press conference ever. Behind him, set in standards, were the blue presidential flag and the American flag. "Like an opera singer about to go on the stage," Roosevelt invariably appeared nervous before a conference began, fidgeting with his cigarette holder, fingering the trinkets on his desk, exchanging self-conscious jokes with the reporters in the front row. Once the action started, however, with the doorkeeper's shout of "all-in," the president seemed to relax, conducting the flow of questions and conversation with such professional skill that the columnist Heywood Broun once called him "the best newspaperman who has ever been President of the United States."

For seven years, twice a week, the president had sat down with these reporters, explaining legislation, announcing appointments, establishing friendly contact, calling them by their first names, teasing them about their hangovers, exuding warmth and accessibility. Once, when a correspondent narrowly missed getting on Roosevelt's train, the president covered for him by writing his copy until he could catch up. Another time, when the mother of a bachelor correspondent died, Eleanor Roosevelt attended the funeral services, and then she and the president invited him for their Sunday family supper of scrambled eggs. These acts of friendship -- repeated many times over -- helped to explain the paradox that, though 80 to 85 percent of the newspaper publishers regularly opposed Roosevelt, the president maintained excellent relations with the working reporters, and his coverage was generally full and fair. "By the brilliant but simple trick of making news and being news," historian Arthur Schlesinger observed, "Roosevelt outwitted the open hostility of the publishers and converted the press into one of the most effective channels of his public leadership."

"History will like to say the scene [on May 10] was tense," Mark Sullivan wrote. "It was not....On the President's part there was consciousness of high events, yet also complete coolness....The whole atmosphere was one of serious matter-of-factness."

"Good morning," the president said, and then paused as still more reporters filed in. "I hope you had more sleep than I did," he joked, drawing them into the shared experience of the crisis. "I guess most of you were pretty busy all night."

"There isn't much I can say about the situation....I can say, personally, that I am in full sympathy with the very excellent statement that was given out, the proclamation, by the Queen of the Netherlands." In that statement, issued earlier that morning, Queen Wilhelmina had directed "a flaming protest against this unprecedented violation of good faith and all that is decent in relations between cultured states."

Asked if he would say what he thought the chances were that the United States could stay out of the war, the president replied as he had been replying for months to similar questions. "I think that would be speculative. In other words, don't for heaven's sake, say that means we may get in. That would be again writing yourself off on the limb and sawing it off." Asked if his speech that night would touch on the international situation, Roosevelt evoked a round of laughter by responding: "I do not know because I have not written it."

On and on he went, his tone in the course of fifteen minutes shifting from weariness to feistiness to playfulness. Yet, in the end, preserving his options in this delicate moment, he said almost nothing, skillfully deflecting every question about America's future actions. Asked at one point to compare Japanese aggression with German aggression, he said he counted seven ifs in the question, which meant he could not provide an answer. Still, by the time the senior wire-service man brought the conference to an early close, "partly in consideration of the tired newspaper men and partly in consideration of the President," the reporters went away with the stories they needed for the next day's news.

While the president was holding his press conference, Eleanor was in a car with her secretary, Malvina Thompson, heading toward the Choate School near the village of Wallingford, Connecticut. Built in the middle of three hundred acres of farm and woodland, with rolling hills stretching for many miles beyond, Choate was a preparatory school for young boys. The students were mostly Protestant, though in recent years a few Catholics had been admitted, including the two sons of Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, Joe Jr. and John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Like Missy, Malvina Thompson, known to her friends as Tommy, was a fixture in the Roosevelt household, as critical to Eleanor's life as Missy was to Franklin's. Short and stocky, with brown hair and a continual wrinkle in the bridge of her nose, the forty-eight-year-old Tommy had started working for Eleanor when Franklin was governor of New York. She had married Frank Scheider, a teacher in the New York public schools, in 1921 and divorced him in 1939. She had no children. She had her own room in every Roosevelt house: a sitting room and bedroom in the White House, a bedroom in Eleanor's Greenwich Village apartment, and a suite of rooms at ValKill, Eleanor's cottage at Hyde Park.

Born of "good old Vermont granite stock," Tommy was smart and tough with a wry sense of humor. "When she walked," a relative recalled, "she gave the impression of saying 'You'd better get out of my way or else.'" Tommy was the person, Eleanor said in 1938, "who makes life possible for me."

During the past seven years in the White House, Eleanor and Tommy traveled more than 280,000 miles around the United States, the equivalent of nearly a hundred cross-country trips. Franklin called Eleanor his "will o' the wisp" wife. But it was Franklin who had encouraged her to become his "eyes and ears," to gather the grass-roots knowledge he needed to understand the people he governed. Unable to travel easily on his own because of his paralysis, he had started by teaching Eleanor how to inspect state institutions in 1929, during his first term as governor.

"It was the best education I ever had," she later said. Traveling across the state to inspect institutions for the insane, the blind, and the aged, visiting state prisons and reform schools, she had learned, slowly and painfully, through Franklin's tough, detailed questions upon her return, how to become an investigative reporter.

Her first inspection was an insane asylum. "All right," Franklin told her, "go in and look around and let me know what's going on there. Tell me how the inmates are being treated." When Eleanor returned, she brought with her a printed copy of the day's menu. "Did you look to see whether they were actually getting this food?" Franklin asked. "Did you lift a pot cover on the stove to check whether the contents corresponded with this menu?" Eleanor shook her head. Her untrained mind had taken in a general picture of the place but missed all the human details that would have brought it to life. "But these are what I need," Franklin said. "I never remembered things until Franklin taught me," Eleanor told a reporter. "His memory is really prodigious. Once he has checked something he never needs to look at it again."

"One time," she recalled, "he asked me to go and look at the state's tree shelter-belt plantings. I noticed there were five rows of graduated size....When I came back and described it, Franklin said: 'Tell me exactly what was in the first five rows. What did they plant first?' And he was so desperately disappointed when I couldn't tell him, that I put my best efforts after that into missing nothing and remembering everything."

In time, Eleanor became so thorough in her inspections, observing the attitudes of patients toward the staff, judging facial expressions as well as the words, looking in closets and behind doors, that Franklin set great value on her reports. "She saw many things the President could never see," Labor Secretary Frances Perkins said. "Much of what she learned and what she understood about the life of the people of this country rubbed off onto FDR. It could not have helped to do so because she had a poignant understanding...Her mere reporting of the facts was full of a sensitive quality that could never be escaped....Much of his seemingly intuitive understanding -- about labor situations...about girls who worked in sweatshops -- came from his recollections of what she had told him."

During Eleanor's first summer as first lady, Franklin had asked her to investigate the economic situation in Appalachia. The Quakers had reported terrible conditions of poverty there, and the president wanted to check these reports. "Watch the people's faces," he told her. "Look at the conditions of the clothes on the wash lines. You can tell a lot from that." Going even further, Eleanor descended the mine shafts, dressed in a miner's outfit, to absorb for herself the physical conditions in which the miners worked. It was this journey that later provoked the celebrated cartoon showing two miners in a shaft looking up: "Here Comes Mrs. Roosevelt!"

At Scott's Run, near Morgantown, West Virginia, Eleanor had seen children who "did not know what it was to sit down at a table and eat a proper meal." In one shack, she found a boy clutching his pet rabbit, which his sister had just told him was all there was left to eat. So moved was the president by his wife's report that he acted at once to create an Appalachian resettlement project.

The following year, Franklin had sent Eleanor to Puerto Rico to investigate reports that a great portion of the fancy embroidered linens that were coming into the United States from Puerto Rico were being made under terrible conditions. To the fury of the rich American colony in San Juan, Eleanor took reporters and photographers through muddy alleys and swamps to hundreds of foul-smelling hovels with no plumbing and no electricity, where women sat in the midst of filth embroidering cloth for minimal wages. Publicizing these findings, Eleanor called for American women to stop purchasing Puerto Rico's embroidered goods.

Later, Eleanor journeyed to the deep South and the "Dustbowl." Before long, her inspection trips had become as important to her as to her husband. "I realized," she said in a radio interview, "that if I remained in the White House all the time I would lose touch with the rest of the world....I might have had a less crowded life, but I would begin to think that my life in Washington was representative of the rest of the country and that is a dangerous point of view." So much did Eleanor travel, in fact, that the Washington Star once printed a humorous headline: "Mrs. Roosevelt Spends Night at White House."

So it was not unusual that, on May 10, 1940, Eleanor found herself away from home, driving along a country road in central Connecticut. Months earlier, she had accepted the invitation of the headmaster, George St. John, to address the student body. Now, in the tense atmosphere generated by the Nazi invasion of Western Europe, her speech assumed an added measure of importance. As she entered the Chapel and faced the young men sitting in neat rows before her, she was filled with emotion.

"There is something very touching in the contact with these youngsters," she admitted, "so full of fire and promise and curiosity about life. One cannot help dreading what life may do to them....All these young things knowing so little of life and so little of what the future may hold."

Eleanor's forebodings were not without foundation. Near the Chapel stood the Memorial House, a dormitory built in memory of the eighty-five Choate boys who had lost their lives in the Great War. Now, as she looked at the eager faces in the crowd and worried about a European war spreading once again to the United States, she wondered how many of them would be called to give their lives for their country.

For several days, Eleanor's mind had been preoccupied by old wars. "I wonder," she wrote in her column earlier that week, "that the time does not come when young men facing each other with intent to kill do not suddenly think of their homes and their loved ones and realizing that those on the other side must have the same thoughts, throw away their weapons of murder."

Talking with her young friend Joe Lash that week at lunch, Eleanor admitted she was having a difficult time sorting out her feelings about the war. On the one hand, she was fully alert to the magnitude of Hitler's threat. On the other hand, she agreed with the views of the American Youth Congress, a group of young liberals and radicals whom Eleanor had defended over the years, that the money spent on arms would be much better spent on education and medical care. Her deepest fear, Lash recorded in his diary, was that nothing would come out of this war different from the last war, that history would repeat itself. And because of this sinking feeling, she could not put her heart into the war.

Building on these feelings in her speech to the boys of Choate, Eleanor stressed the importance of renewing democracy at home in order to make the fight for democracy abroad worthwhile. This argument would become her theme in the years ahead, as she strove to give positive meaning to the terrible war. "How to preserve the freedoms of democracy in the world. How really to make democracy work at home and prove it is worth preserving....These are the questions the youth of today must face and we who are older must face them too."

Eleanor's philosophical questions about democracy were not the questions on the president's mind when he met with his Cabinet at two that afternoon. His concerns as he looked at the familiar faces around the table were much more immediate: how to get a new and expanded military budget through the Congress, how to provide aid to the Allies as quickly as possible, how to stock up on strategic materials; in other words, how to start the complex process of mobilizing for war.

The president opened the proceedings, as usual, by turning to Cordell Hull, his aging secretary of state, for the latest news from abroad. A symbol of dependability, respected by liberals and conservatives alike, the tall gaunt Tennessean, with thick white hair and bright dark eyes, had headed the department since 1933. Hull spoke slowly and softly as he shared the latest bulletins from his embassies in Europe, his slumped shoulders and downcast eyes concealing the stubborn determination that had characterized his long and successful career in the Congress as a representative and senator from Tennessee. In Holland, it was reported with a tone of optimism that later proved unfounded, the Dutch were beginning to recapture the airports taken by the Germans the night before. In Belgium, too, it was said, the Allied armies were holding fast against the German thrusts. But the mood in the room darkened quickly as the next round of bulletins confirmed devastating tales of defeat at the hands of the Germans.

After hearing Hull, the president traditionally called on Henry Morgenthau, his longtime friend and secretary of the Treasury. Just before the Cabinet meeting had convened, Morgenthau had received word that the Belgian gold reserves had been safely evacuated to France, and that much of the Dutch gold was also safe. But this was the extent of the good news Morgenthau had to report. All morning long, Morgenthau had been huddled in meetings with his aides, looking at the dismal figures on America's preparedness, wondering how America could ever catch up to Germany, since it would take eighteen months to deliver the modern weapons of war even if the country went into full-scale mobilization that very day.

Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, the only woman in the Cabinet, tended to talk a great deal at these meetings, "as though she had swallowed a press release." But on this occasion she remained silent as the conversation was carried by Harry Hopkins, the secretary of commerce, who was present at his first Cabinet meeting in months.

For the past year and a half, Hopkins had been in and out of hospitals while doctors tried to fix his body's lethal inability to absorb proteins and fats. His health had begun to deteriorate in the summer of 1939, when, at the height of his power as director of the Works Progress Administration, he was told that he had stomach cancer. A ghastly operation followed which removed the cancer along with three-quarters of his stomach, leaving him with a severe form of malnutrition. Told in the fall of 1939 that Hopkins had only four weeks to live, Roosevelt took control of the case himself and flew in a team of experts, whose experiments with plasma transfusions arrested the fatal decline. Then, to give Hopkins breathing space from the turbulence of the WPA, Roosevelt appointed him secretary of commerce. Even that job had proved too much, however: Hopkins had been able to work only one or two days in the past ten months.

Yet, on this critical day, the fifty-year-old Hopkins was sitting in the Cabinet meeting in the midst of the unfolding crisis. "He was to all intents and purposes," Hopkins' biographer Robert Sherwood wrote, "a finished man who might drag out his life for a few years of relative inactivity or who might collapse and die at any time." His face was sallow and heavy-lined; journalist George Creel once likened his weary, melancholy look to that of "an ill-fed horse at the end of a hard day," while Churchill's former daughter-in-law, Pamela Churchill Harriman, compared him to "a very sad dog." Given his appearance -- smoking one cigarette after another, his brown hair thinning, his shoulders sagging, his frayed suit baggy at the knees -- "you wouldn't think," a contemporary reporter wrote, "he could possibly be important to a President."

But when he spoke, as he did at length this day on the subject of the raw materials needed for war, his sickly face vanished and a very different face appeared, intelligent, good-humored, animated. His eyes, which seconds before had seemed beady and suspicious, now gleamed with light. Sensing the urgency of the situation, Hopkins spoke so rapidly that he did not finish half of his words, as though, after being long held back, he wanted to make up for lost time. It was as if the crisis had given him a renewed reason for living; it seemed, in reporter Marquis Childs' judgment at the time, "to galvanize him into life." From then on, Childs observed, "while he would still be an ailing man, he was to ignore his health." The curative impact of Hopkins' increasingly crucial role in the war effort was to postpone the sentence of death the doctors had given him for five more years.

Even Hopkins' old nemesis, Harold Ickes, felt compelled to pay attention when Hopkins reported that the United States had "only a five or six months supply of both rubber and tin, both of which are absolutely essential for purposes of defense." The shortage of rubber was particularly worrisome, since rubber was indispensable to modern warfare if armies were to march, ships sail, and planes fly. Hitler's armies were rolling along on rubber-tired trucks and rubber-tracked tanks; they were flying in rubber-lined high-altitude suits in planes equipped with rubber de-icers, rubber tires, and rubber life-preserver rafts. From stethoscopes and blood-plasma tubing to gas masks and adhesive tape, the demand for rubber was endless. And with Holland under attack and 90 percent of America's supply of rubber coming from the Dutch East Indies, something had to be done.

Becoming more and more spirited as he went on, Hopkins outlined a plan of action, starting with the creation of a new corporation, to be financed by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, whose purpose would be to go into the market and buy at least a year's supply of rubber and tin. This step would be only the first, followed by the building of synthetic-rubber plants and an effort to bring into production new sources of natural rubber in South America. Hopkins' plan of action met with hearty approval.

While Hopkins was speaking, word came from London that Neville Chamberlain had resigned his post as prime minister. This dramatic event had its source in the tumultuous debate in the Parliament over the shameful retreat of the British Expeditionary Force from Norway three weeks earlier. Responding to clamorous cries for his resignation, Chamberlain had stumbled badly by personalizing the issue and calling for a division to show the strength of his support. "I welcome it, indeed," he had said. "At least we shall see who is with and who is against us and I will call on my friends to support me in the lobby tonight."

But the division had not turned out as Chamberlain expected: Tory officers in uniform, feeling the brunt of Britain's lack of preparedness, surged into the Opposition lobby to vote against the government. In all, over thirty Conservatives deserted Chamberlain, and a further sixty abstained, reducing the government's margin from two hundred to eighty-one. Stunned and disoriented, Chamberlain recognized he could no longer continue to lead unless he could draw Labour into a coalition government. For a moment earlier that day, the German invasion of the Low Countries threatened to freeze Chamberlain in place, but the Labour Party refused his appeals for a national government. "Prime Minister," Lord Privy Seal Clement Attlee bluntly replied, "our party won't have you and I think I am right in saying that the country won't have you either." The seventy-one-year-old prime minister had little choice but to step down.

Then, when the king's first choice, Lord Halifax, refused to consider the post on the grounds that his position as a peer would make it difficult to discharge his duties, the door was opened for Winston Churchill, the complex Edwardian man with his fat cigars, his gold-knobbed cane, and his vital understanding of what risks should be taken and what kind of adversary the Allies were up against. For nearly four decades, Churchill had been a major figure in public life. The son of a lord, he had been elected to Parliament in 1900 and had served in an astonishing array of Cabinet posts, including undersecretary for the colonies, privy councillor, home secretary, first lord of the admiralty, minister of munitions, and chancellor of the Exchequer. He had survived financial embarrassment, prolonged fits of depression, and political defeat to become the most eloquent spokesman against Nazi Germany. From the time Hitler first came to power, he had repeatedly warned against British efforts to appease him, but no one had listened. Now, finally, his voice would be heard. "Looking backward," a British writer observed, "it almost seems as though the transition from peace to war began on that day when Churchill became Prime Minister."

Responding warmly to the news of Churchill's appointment, Roosevelt told his Cabinet he believed "Churchill was the best man that England had." From a distance, the two leaders had come to admire each other: for years, Churchill had applauded Roosevelt's "valiant effort" to end the depression, while Roosevelt had listened with increasing respect to Churchill's lonely warnings against the menace of Adolf Hitler. In September 1939, soon after the outbreak of the war, when Churchill was brought into the government as head of the admiralty, Roosevelt had initiated the first in what would become an extraordinary series of wartime letters between the two men. Writing in a friendly, but respectful tone, Roosevelt had told Churchill: "I shall at all times welcome it if you will keep me in touch personally with everything you want me to know about. You can always send sealed letters through your pouch or my pouch." Though relatively few messages had been exchanged in the first nine months of the war, the seeds had been planted of an exuberant friendship, which would flourish in the years to come.

Once the Cabinet adjourned, Roosevelt had a short meeting with the minister of Belgium, who was left with only $35 since an order to freeze all credit held by Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg had gone into effect, earlier that morning. After arrangements were made to help him out, there began a working session on the speech Roosevelt was to deliver that night to a scientific meeting.

Then Roosevelt, not departing from his regular routine, went into his study for the cocktail hour, the most relaxed time of his day. The second-floor study, crowded with maritime pictures, models of ships, and stacks of paper, was the president's favorite room in the White House. It was here that he read, played poker, sorted his beloved stamps, and conducted most of the important business of his presidency. The tall mahogany bookcases were stuffed with books, and the leather sofas and chairs had acquired a rich glow. Any room Roosevelt spent time in, Frances Perkins observed, "invariably got that lived-in and overcrowded look which indicated the complexity and variety of his interests and intentions." Missy and Harry Hopkins were there, along with Pa Watson and Eleanor's houseguest, the beautiful actress Helen Gahagan Douglas. The cocktail hour, begun during Roosevelt's years in Albany, had become an institution in Roosevelt's official family, a time for reviewing events in an informal atmosphere, a time for swapping the day's best laughs. The president always mixed the drinks himself, experimenting with strange concoctions of gin and rum, vermouth and fruit juice.

During the cocktail hour, no more was said of politics or war; instead the conversation turned to subjects of lighter weight -- to gossip, funny stories, and reminiscences. With Missy generally presiding as hostess, distributing the drinks to the guests, Roosevelt seemed to find complete relaxation in telling his favorite stories over and over again. Some of these stories Missy must have heard more than twenty or thirty times, but, like the "good wife," she never let her face betray boredom, only delight at the knowledge that her boss was having such a good time. And with his instinct for the dramatic and his fine ability to mimic, Roosevelt managed to tell each story a little differently each time, adding new details or insights.

On this evening, there was a delicious story to tell. In the Congress there was a Republican representative from Auburn, New York, John Taber, who tended to get into shouting fits whenever the subject of the hated New Deal came up. In a recent debate on the Wage and Hour amendments, he had bellowed so loudly that he nearly swallowed the microphone. On the floor at the time was Representative Leonard Schultz of Chicago, who had been deaf in his left ear since birth. As Mr. Taber's shriek was amplified through the loudspeakers, something happened to Mr. Schultz. Shaking convulsively, he staggered to the cloakroom, where he collapsed onto a couch, thinking he'd been hit in an air raid. He suddenly realized that he could hear with his left ear -- for the first time in his life -- and better than with his right. When doctors confirmed that Mr. Schultz's hearing was excellent, Mr. Taber claimed it was proof from God that the New Deal should be shouted down!

Harry Hopkins was no stranger to these intimate gatherings. Before his illness, he had been one of Roosevelt's favorite companions. Like Roosevelt, he was a great storyteller, sprinkling his tales with period slang and occasional profanity. Also like Roosevelt, he saw the humor in almost any situation, enjoying gags, wisecracks, and witticisms. "I didn't realize how smart Harry was," White House secretary Toi Bachelder later remarked, "because he was such a tease and would make a joke of everything."

Missy was undoubtedly as delighted as her boss to see Harry back at the White House, though her playful spirit most likely masked the genuine pleasure she took in the company of this unusual man. Once upon a time, after Hopkins' second wife, Barbara, died of cancer, there had been talk of a romance between Missy and Harry. In a diary entry for March 1939, Harold Ickes reported a conversation with presidential adviser Tommy Corcoran in which Corcoran had said "he would not be surprised if Harry should marry Missy." In that same entry, Ickes recorded a dinner conversation between his wife, Jane Ickes, and Harry Hopkins in which they "got to talking about women -- a favorite subject with Harry. He told Jane that Missy had a great appeal for him."

Among Hopkins' personal papers, there are many affectionate notes to Missy. During a spring weekend in 1939 when Missy was at the St. Regis in New York, Hopkins sent her a telegram. "Vic and I arriving Penn Station 8. Going direct to St. Regis. Make any plans you want but include us." On another occasion, when Hopkins was in the hospital for a series of tests, he wrote her a long, newsy letter but admitted that "the real purpose of this letter is to tell you not to forget me....Within a day or two I expect to be out riding in the country for an hour or so each day and only wish you were with me."

The president, Harry, and Missy had journeyed together to Warm Springs in the spring of 1938. "There is no one here but Missy -- the President and me -- so life is simple -- ever so informal and altogether pleasant," Hopkins recorded. "Lunch has usually been FDR with Missy and me -- these are the pleasantest because he is under no restraint and personal and public business is discussed with the utmost frankness....After dinner the President retreats to his stamps -- magazines and the evening paper. Missy and I will play Chinese checkers -- occasionally the three of us played but more often we read -- a little conversation -- important or not -- depending on the mood."

But if over the years their familiarity had brought Harry and Missy to the point of intimacy, Missy had probably cut it short, as she had cut short every other relationship in her life that might subordinate her great love for FDR. No invitation was accepted by Missy if it meant leaving the president alone. "Even the most ardent swain," Newsweek reported, "is chilled at the thought that, to invite her to a movie he must call up the White House, which is her home." At the end of her working day, Missy preferred to retire to her little suite on the third floor, where, more often than not, she would pick up her phone to hear the president on the line, asking her to come to his study and sit by his side as he sorted his stamps or went through his mail.

If this behavior seemed mistaken in the eyes of her friends, who could not imagine how someone so young and attractive, who "should have been off somewhere cool and gay on a happy weekend," would give up "date after date, month after month, year after year," Missy had no other wish than to be with Roosevelt, her eager eyes watching every movement of his face, marveling at his overwhelming personality, his facility for dealing with people of every sort, his exceptional memory, his unvarying good humor. "Gosh, it will be good to get my eyes on you again," Missy wrote Roosevelt once when he was on a trip. "This place is horrible when you are away."

While Franklin was mixing cocktails, Eleanor was on a train back to Washington from New York. For many of her fellow riders, the time on the train was a time to ease up, to gaze through the windows at the passing countryside, to close their eyes and unwind. But for Eleanor, who considered train rides her best working hours, there was little time to relax. The pile of mail, still unanswered, was huge, and there was a column to be written for the following day. Franklin's cousin Margaret "Daisy" Suckley recalls traveling with Eleanor once on the New York-to-Washington train. "She was working away the whole time with Malvina, and I was sitting there like a dumbbell looking out the window, and suddenly Mrs. Roosevelt said to. Malvina, 'Now I'm going to sleep for fifteen minutes,' and she put her head back on the seat. I looked at my watch, and just as it hit fifteen minutes, she woke up and said, 'Now Tommy, let's go on.' It was amazing. I was stunned."

Even if Eleanor had reached the White House that evening in time for the cocktail hour, she would probably not have joined. Try as she might over the years, Eleanor had never felt comfortable at these relaxed gatherings. Part of her discomfort was toward alcohol itself, the legacy of an alcoholic father who continually failed to live up to the expectations and trust of his adoring daughter. One Christmas, Eleanor's daughter, Anna, and her good friend Lorena Hickok had chipped in to buy some cocktail glasses for Eleanor's Greenwich Village apartment in the hopes she would begin inviting friends in for drinks. "In a funny way," Anna wrote "Hick," as Miss Hickok was called, "I think she has always wanted to feel included in such parties, but so many old inhibitions have kept her from it."

But, despite Anna's best hopes, Eleanor's discomfort at the cocktail hour persisted, suggesting that beyond her fear of alcohol lay a deeper fear of letting herself go, of slackening off the work that had become so central to her sense of self. "Work had become for Eleanor almost as addictive as alcohol," her niece Eleanor Wotkyns once observed. "Even when she thought she was relaxing she was really working. Small talk horrified her. Even at New Year's, when everyone else relaxed with drinks, she would work until ten minutes of twelve, come in for a round of toasts, and then disappear to her room to work until two or three a.m. Always at the back of her mind were the letters she had to write, the things she had to do."

"She could be a crashing bore," Anna's son Curtis Dall Roosevelt admitted. "She was very judgmental even when she tried not to be. The human irregularities, the off-color jokes he loved, she couldn't take. He would tell his stories, many of them made to fit a point, and she would say, 'No, no, Franklin, that's not how it happened.'"

"If only Mother could have learned to ease up," her son Elliott observed, "things would have been so different with Father, for he needed relaxation more than anything in the world. But since she simply could not bring herself to unwind, he turned instead to Missy, building with her an exuberant, laughing relationship, full of jokes, silliness, and gossip."

"Stay for dinner. I'm lonely," Roosevelt urged Harry Hopkins when the cocktail hour came to an end. There were few others at this stage of his life that the president enjoyed as much as Hopkins. With the death in 1936 of Louis Howe, the shriveled ex-newspaperman who had fastened his star to Roosevelt in the early Albany days, helped him conquer his polio, and guided him through the political storms to the White House, the president had turned to Hopkins for companionship. "There was a temperamental sympathy between Roosevelt and Hopkins," Frances Perkins observed. Though widely different in birth and breeding, they both possessed unconquerable confidence, great courage, and good humor; they both enjoyed the society of the rich, the gay, and the well-born, while sharing an abiding concern for the average man. Hopkins had an almost "feminine sensitivity" to Roosevelt's moods, Sherwood observed. Like Missy, he seemed to know when the president wanted to consider affairs of state and when he wanted to escape from business; he had an uncanny instinct for knowing when to introduce a serious subject and when to tell a joke, when to talk and when to listen. He was, in short, a great dinner companion.

As soon as dinner was finished, Roosevelt had to return to work. In less than an hour, he was due to deliver a speech, and he knew that every word he said would be scrutinized for the light it might shed on the crisis at hand. Taking leave of Hopkins, Roosevelt noticed that his friend looked even more sallow and miserable now than he had looked earlier in the day. "Stay the night," the President insisted. So Hopkins borrowed a pair of pajamas and settled into a bedroom suite on the second floor. There he remained, not simply for one night but for the next three and a half years, as Roosevelt, exhibiting his genius for using people in new and unexpected ways, converted him from the number-one relief worker to the number-one adviser on the war. Later, Missy liked to tease: "It was Harry Hopkins who gave George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart the idea for that play of theirs, 'The Man Who Came to Dinner.'"

As the president was preparing to leave for Constitution Hall, he remembered something he had meant to ask Helen Gahagan Douglas during the cocktail hour. There was no time to discuss it now, but, stopping by her room, he told her he had an important question for her and asked if she would meet him in his study when he returned. "Certainly," she replied, and he left to address several thousand scientists and scholars at the Pan American Scientific Congress.

"We come here tonight with heavy hearts," he began, looking out at the packed auditorium. "This very day, the tenth of May, three more independent nations have been cruelly invaded by force of arms....I am glad that we are shocked and angered by the tragic news." Declaring that it was no accident that this scientific meeting was taking place in the New World, since elsewhere war and politics had compelled teachers and scholars to leave their callings and become the agents of destruction, Roosevelt warned against an undue sense of security based on the false teachings of geography: in terms of the moving of men and guns and planes and bombs, he argued, every acre of American territory was closer to Europe than was ever the case before. "In modern times it is a shorter distance from Europe to San Francisco, California than it was for the ships and legions of Julius Caesar to move from Rome to Spain or Rome to Britain."

"I am a pacifist," he concluded, winding up with a pledge that was greeted by a great burst of cheers and applause, "but I believe that by overwhelming majorities...you and I, in the long run if it be necessary, will act together to protect and defend by every means at our command our science, our culture, our American freedom and our civilization."

Buoyed by his thunderous reception, Roosevelt was in excellent humor when he returned to his study to find Helen Gahagan Douglas waiting for him. Just as he was settling in, however, word came that Winston Churchill was on the telephone. Earlier that evening, Churchill had driven to Bucking-ham Palace, where King George VI had asked him to form a government. Even as Churchill agreed to accept the seals of office, British troops were pouring into Belgium, wildly cheered by smiling Belgians, who welcomed them with flowers. The change was made official at 9 p.m., when Chamberlain, his voice breaking with emotion, resigned. It had been a long and fateful day for Britain, but now, though it was nearly 3 a.m. in London, Churchill apparently wanted to touch base with his old letter-writing companion before going to sleep.

Though there is no record of the content of this first conversation between the new prime minister of England and the president of the United States, Churchill did reveal that when he went to bed that night, after the extraordinary events of an extraordinary day, he was conscious of "a profound sense of relief. At last I had the authority to give directions over the whole scene. I felt as if I were walking with Destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and this trial."

"Therefore," Churchill concluded, "although impatient for morning, I slept soundly and had no need for cheering dreams. Facts are better than dreams." He had achieved the very position he had imagined for himself for so many years.